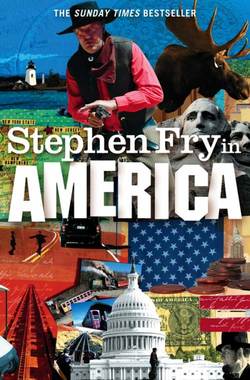

Читать книгу Stephen Fry in America - Stephen Fry, Stephen (Audiobook Narrator) Fry - Страница 37

ОглавлениеPENNSYLVANIA

KEY FACTS

Abbreviation:

PA

Nicknames:

The Keystone State, The Quaker State

Capital:

Harrisburg

Flower:

Mountain laurel

Tree:

Eastern hemlock

Bird:

Ruffed grouse

Toy:

Slinky (I’m not making this up)

Motto:

Virtue, Liberty and Independence

Well-known residents and natives:

Benjamin Franklin, Gertrude Stein, Wallace Stevens, John Updike, August Wilson, James A. Michener, Dean Koontz, John O’Hara, Thomas Eakins, Pearl S. Buck, Man Ray, Andy Warhol, Marilyn Horne, W.C. Fields, the Barrymores, David O. Selznick, Gene Kelly, Jayne Mansfield, Grace Kelly, Henry Mancini, Charles Bronson, Richard Gere, Kevin Bacon, Sharon Stone, Will Smith, M. Night Shyamalan, Perry Como, Bill Haley, Chubby Checker, Keith Jarrett, Hall and Oates, Christina Aguilera.

PENNSYLVANIA

‘There is something in the hope and idealism of this frustrating and contradictory nation that still makes my spirits soar.’

The Commonwealth of Pennsylvania is the only state to be named after a person. Oh, apart from Washington of course. And New York, because that was named not after the city of York, but after James, Duke of York. Oh, and the Carolinas were named after King Charles I. And Virginia after Elizabeth, the Virgin Queen. And Maryland after Henrietta Maria, wife of Charles I … all right. All right. So actually lots of states have been named after people. Pennsylvania is just one. It gets its name from William Penn, the Quaker who was the founder and absolute controller of what was in its day the largest of the colonial states. Although in strict fact it was named after his father, Admiral Sir William Penn, who had lent Charles II a great deal of money and received in return the rights to the land west of the Delaware River on behalf of his son. The Admiral himself was not a Quaker (you cannot really have a Quaker with a military rank, it doesn’t compute) and did not like the fact that his son was, but William Jnr, a remarkable man who had braved much contempt, imprisonment and persecution for his pacifist, heterodox beliefs, used the family money, his father’s favour with the King and his own intelligence and natural leadership skills to carve out this great tract of land, which functioned independently under a democratic constitution long before independence came.

Philadelphia (an adaptation of the Greek for ‘brotherly love’) is the chief city, although not the capital. Here can be found Independence Hall and the famously, and perhaps proleptically, cracked Liberty Bell amongst other tourist attractions.

Although America was consecrated, if that is the right word (and you will soon see why I chose it ) on July 4th, 1776 in Philadelphia when John Hancock became the first to append his name (one’s ‘John Hancock’ in America is to this day one’s signature) to the Declaration of Independence, for me and for many the moment America grew up was when it was re-consecrated ‘four score and seven’ years later on a battlefield 140 miles to the west of Philadelphia, towards which I am now driving, under heavy clouds and through torrential rain.

Gettysburg

The weather improves with dramatic suddenness the moment I pass the sign that tells me I have arrived in Gettysburg. The clouds depart, a clear autumnal sun lights the still bright leaves of the trees around the cemetery and makes the puddles glint and flash as I pass.

I am welcomed by Abraham Lincoln. Well, by an actor, historian and lookalike called Jim. Jim conducts me around the cemetery, contriving to stay in character in a way that is not irritating or twee.

It might seem something of a puzzle that a nation born out of such high ideals, such humanitarian vision and such intellectual clarity and rational enlightenment as America should have descended, by the 1860s, into the bloodiest war that humanity had ever recorded. Man for man, no conflict has ever been more attritional and deadly than the American Civil War of 1861–65.

Jim offers the view that it is perhaps only in the clear light of history that one can argue the war had to happen. America’s written constitution, with its lofty air of permanence and marmoreal splendour, had not addressed what America might be in the modern world. To us all now the Civil War was, or should have been, about the evils of slavery and that is how most will think of it. But many of the Northerners who fought so bitterly, and with such ample funding, were fighting because their paymasters and political leaders looked across the Atlantic at the Industrial Revolution that was propelling Britain to unimagined heights of prosperity and they saw that their own country, with its two economies, one powered by slavery and the other not, was at a huge disadvantage. Slavery was outlawed across Europe, whose countries would not trade with America – not so much out of moral repugnance as annoyance at the unfair advantage a labour bill of zero gave the plantation owners. The North wanted to create conditions for a modern industrial state, an enterprise economy, and to do that it had to bid an enforced goodbye to the plantations. It was no good having two Americas: a neighbour with a slave economy was never going to allow the kind of commercial equity the North demanded. So it was, au fond