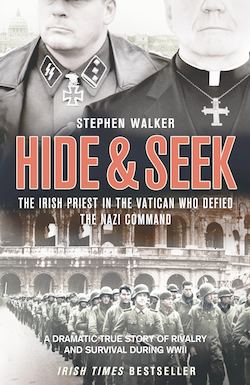

Читать книгу Hide and Seek: The Irish Priest in the Vatican who Defied the Nazi Command. The dramatic true story of rivalry and survival during WWII. - Stephen Walker - Страница 10

ОглавлениеChapter Six OPERATION ESCAPE

‘God will protect us all’

Henrietta Chevalier to Hugh O’Flaherty

One evening in 1943, as the light was fading, Hugh O’Flaherty left the Vatican and made his way to the other side of Rome. At Piazza Salerno he walked round a corner, then went through an archway between a grocer’s shop and a butcher’s. Slowly he climbed three flights of steps. He read the numbers on the doors and then, finding the correct address, rang the bell.

He was quickly ushered in. Once inside the flat in Via Imperia, he towered over Henrietta Chevalier, who stood just five feet four inches tall. The attractive middle-aged woman had neat hair and wore earrings and a necklace. A widow from Malta living on a small pension, she had lost her husband just before the start of the war. Her English was perfect, though she spoke with a trace of a Maltese accent. She had six daughters and two sons, and one of her boys worked at the Swiss embassy, while the other was being held in a prison camp. Although her home was small she had agreed to house two escaped French soldiers. O’Flaherty was delighted that she was willing to help, but he needed to impress on her the dangers of taking in escaped prisoners.

‘You do not have to do it,’ he told her, adding that those found harbouring prisoners of war could be executed. He said he would take the men away if she had any doubts about their staying in her home. If Henrietta was scared, she certainly did not show it. In fact she seemed quite relaxed about the priest’s warning. ‘What are you worrying about, Monsignor?’ she replied. ‘God will protect us all.’

A quick glance round the flat showed the monsignor how important Henrietta’s faith was to her. Fittingly, a tapestry of Our Lady of Pompeii, who traditionally helped those in need, hung in one of the two bedrooms. On a table sat a small statue of St Paul. Prayer was an important part of Henrietta’s daily life. She firmly believed she and her family would be safe and told her visitor she was happy to help for as long as possible. O’Flaherty’s new-found Maltese friend would stick to that promise.

From that night on, the Chevaliers’ tiny flat would never be the same again. Their military guests would sleep on mattresses and Henrietta and her children would share the beds. Space would be at a premium and soon there would be a daily queue for the bathroom. The changed circumstances would have to be kept secret. The flat was now out of bounds to all but family members. The Chevaliers’ friends couldn’t come to see them and the girls could not invite visitors. But it wasn’t all bad news. For the younger daughters the new male house guests were a novelty and brought a sense of fun. Within days flat number nine would echo to the strains of endless gramophone records and Henrietta’s young girls would have a choice of dancing partners.

Back in his room in the German College, Hugh O’Flaherty was happy in the knowledge that he had secured shelter and a willing host for the two escapees.

By September 1943 the Germans were edging closer to taking over Rome. In the same month O’Flaherty had three new arrivals to welcome. Henry Byrnes was a captain in the Royal Canadian Army Corps. He arrived in style at the Holy See. A prisoner of war, he was being marched to the Castro Pretorio barracks in Rome when he and two colleagues gave the soldiers guarding them the slip. Byrnes, John Munroe Sym, a major in the Seaforth Highlanders, and Roy Elliot, a sub-lieutenant in the Royal Navy, met an Italian doctor. Fortunately Luigi Meri de Vita was a friendly soul, well disposed towards escaped Allied servicemen. He put the three escapees in his car and drove them across Rome to the Vatican. After managing to get into the Holy See, the three men quickly found their way to Hugh O’Flaherty’s door.

The monsignor immediately put Byrnes and Elliot to work. The pair began to compile a list of Allied servicemen they knew were in hiding across Italy. Once the paperwork was complete, Byrnes passed the details on to Father Owen Sneddon, a contemporary of the monsignor who was now assisting the Escape Line. Sneddon, a New Zealander, worked as a broadcaster for the English-language Vatican Radio service. The station was part of the Vatican’s communication network and, although the Pope technically controlled it, it was run day to day by the Jesuit Father Filippo Soccorsi. The station was an important tool for the Escape Line, but broadcasters had to be careful because the Germans monitored the output and each broadcast was translated.

Once Father Sneddon was ready he peppered his broadcasts with the names supplied by Byrnes and Elliot. The details were picked up by the War Office in London, which informed the men’s families that their loved ones were alive. It was an old trick that O’Flaherty had first perfected when he was an official visitor to the POW camps. When the monsignor returned to Rome from seeing prisoners, he would pass on their personal details to Father Sneddon. It was a simple way to let people know that their relative was alive, and this method went undetected by the Germans.

The Vatican reflected the outside world and the atmosphere in the Holy See was nervous and apprehensive. Osborne and O’Flaherty wondered what their lives would be like in a post-Mussolini world. Rumours filled the void of uncertainty. There was much talk about an Italian surrender followed by a German invasion of Rome. One fear that wouldn’t go away was a suggestion that the Germans would capture the Vatican and seize the Pope and take him abroad.

There was good reason for this worry. Days after Mussolini’s kidnapping, in the Wolf’s Lair an angry Hitler berated the Pope and the Holy See: ‘Do you think the Vatican impresses me? I couldn’t care less. We will clear out that gang of swine.’

Hitler was considering kidnapping the Pope, arresting the King and Marshal Badoglio, and occupying the Vatican City. The threat to seize Pope Pius XII was believed to be so likely that, in early August, the Vatican’s Secretary of State, Cardinal Maglione, summoned all the cardinals in Rome to a special meeting. He explained that the Germans had plans to seize Rome and then take control of the Vatican buildings and remove the Pope. The threat was regarded as so plausible that the commander of the Pope’s Swiss Guards was ordered not to offer any resistance when the German troops tried to gain access to the Vatican.

Staff inside the Holy See started to take precautions should the Germans seize the site. Sensitive Church documents were hidden across the Vatican and some diplomatic papers were burnt. Sir D’Arcy Osborne, now beginning to worry that his personal diary would be seized if the Nazis took over, had to think carefully about what he was committing to paper. He made some entries designed to fool prying eyes and others which were light on detail. At one stage he wrote: ‘I wish I could put down all the facts and rumours these days, but I can’t. It is a pity for the sake of the diary.’

The Germans were continuing to watch the Vatican intently, and the behaviour of Badoglio’s administration was put under constant scrutiny. The Nazis knew that an Italian surrender was coming after German code-breakers listened to a conversation between Franklin D. Roosevelt and Winston Churchill in which the two leaders discussed an armistice. The Nazis had also discovered that secret talks were underway between the Allies and the Italians and were able to dismiss Badoglio’s official response that he was fully supportive of the Nazi war effort. Because they suspected that it was only a matter of time before the Italians surrendered, the discovery and restoration of Benito Mussolini as leader was becoming urgent.

The events in Rome and the questions surrounding Italy’s future in the war had initially overshadowed the efforts to find Mussolini, but now senior Nazis were becoming restless. They put pressure on Kappler, making it clear that he must locate the former dictator within days.

Kappler’s network of informers, who were being partially funded by Skorzeny’s fake banknotes, had so far failed to deliver solid intelligence on Mussolini’s whereabouts. Rumours abounded as to his precise location. Every time a story surfaced or there was an alleged sighting of the man, Kappler and his team had to investigate it. One rumour suggested that he was being held in hospital in Rome awaiting an operation, but Kappler discovered this to be untrue. There was another story that Mussolini hadn’t left the royal residence at Villa Savoia, but that also proved a false trail. Each alleged sighting of Il Duce contradicted the last one.

Trying to stay one step ahead of the Germans, the Badoglio administration began to move Mussolini around. Through a contact in the Italian police, Kappler had learnt that the country’s most famous prisoner had first been taken by ambulance from Villa Savoia to the Podgora barracks in Via Quintino Sella, a thirty-minute high-speed drive from the royal residence. Kappler was also able to establish which part of the building Mussolini had been held in. He now knew that he had slept in a camp bed, in a small office which overlooked the parade ground where the cadets marched.

Fascinating though this information was, for Kappler it was all too late. Mussolini’s captors had already moved their precious charge on. He had been driven from Rome to the port of Gaeta, where he was put aboard a vessel named the Persefone and taken to the island of Ponza, twenty-five miles to the north. Ponza, which was around five miles long, had a history as a penal colony.

Kappler’s efforts to find Mussolini did not go unnoticed. The Führer himself was keeping an eye on his attempts to track down the former dictator. The previous month, August 1943, Hitler had called the police attaché in to see him. Having completed four years in Rome, Kappler thought he was about to be moved elsewhere in the Third Reich, but Hitler had other ideas. For the young SS man the meeting went better than he had expected. Hitler praised him and made it clear that his work in Rome was very important. He told him that he valued his contacts and that he was needed in the hunt for Mussolini and for future work organizing surveillance in the city. Ironically the very mission that Kappler had doubts about, the rescue of Mussolini, had secured his future in Rome.

Day by day Kappler’s office tried to piece together Mussolini’s secret journey from Villa Savoia. The police attaché’s staff tried a variety of methods. Pro-Nazi officers in the Italian Army and police force were constantly badgered for titbits of information. Staff also monitored the airwaves for any unusual reports or coded messages.

Finally they made a breakthrough. One of Kappler’s agents, who had been listening to Italian communication networks, came across an intriguing phrase. He heard the words, ‘Security preparations around the Gran Sasso complete.’ The message had been sent by an officer named Gueli, one of Mussolini’s captors, and was meant for one of his superiors.

At 9 p.m. on 5 September Kappler sent a cable to senior offices in Berlin informing them that it was extremely likely that Mussolini was in the vicinity of the Gran Sasso mountain. He also informed that he had sent out a fresh reconnaissance party which would report back shortly.

Kappler’s team would quickly discover that the former dictator was indeed where they suspected, in the Apennine mountains in the Abruzzo region of eastern Italy. He had been taken by boat from the island of Ponza around Italy to a villa on Maddalena, an island off Sardinia, and from there was flown to the winter resort of Campo Imperatore, near the Gran Sasso. The Italians had chosen Mussolini’s final hiding place wisely. They put him in a room in the Hotel Campo Imperatore, some 7,000 feet above sea level.

As a hiding place the secluded location was ideal, as it was close to the highest peak in the Apennines and could be reached only by a ten-minute ride in a cable car. Although he was surrounded by hotel staff and policemen, Mussolini was the only official guest at the hotel. In conversations with his captors, Gueli and Faiola, he referred to his new surroundings as the ‘highest prison in the world’. As he played cards, read and listened to the radio, Mussolini was unaware that his German allies, after six weeks of searching, were just one step away from rescuing him. Kappler, although a reluctant participant in the manhunt, had proved his worth.

As the rescue plans were finalized the Allies and the Italians struck in different ways. Allied bombers took to the skies over Italy. This time one of their targets was the major headquarters for German troops at Frascati. In a lunchtime attack 400 tonnes of explosives fell on the town, killing and injuring many hundreds of residents and German soldiers. The German military complex was hit and Otto Skorzeny’s quarters were wrecked. Field Marshal Kesselring climbed from the wreckage unharmed. He sensed the bombing was only part of a planned series of events.

Kesselring was right. The attack was a forerunner to an Allied landing in Salerno, but there was more news to come. That evening, as smoke still hung over large parts of Italy, Marshal Badoglio announced on the radio that Italy had surrendered. The Italian leader said that he had requested an armistice from the Allied Commander, General Eisenhower, which had been accepted. Badoglio’s radio address took the Germans by surprise. They had known it was coming, but not when. The timing, rather like that of Mussolini’s kidnap in July, had caught them out.

Colonel Eugen Dollmann, who had been assisting Kappler in the search for Mussolini, was tasked with finding out what was happening on the streets of Rome. There was great confusion in the city, and the rumours were many and varied. These ranged from reports that Allied troops were arriving to seize Rome to stories that German troops were about to take control.

At the German embassy there was an altogether different atmosphere. Staff there, convinced that they were about to be ordered to leave the city, had begun to burn documents. However, amid all the chatter and speculation, Dollmann had secured one critical piece of hard information. When he reported back to Kesselring at the Frascati headquarters, the commander-in-chief of the Southern Front was intrigued. Dollmann had discovered that before the armistice announcement an American general, Maxwell Taylor, had been smuggled into Rome for secret discussions with Badoglio. Taylor, second-in-command of a US airborne unit, had been on a reconnaissance mission to examine the possibility of an airdrop of paratroops close to Rome.

The discussions between Taylor and Badoglio had turned into farce when the Italian leader changed his mind about an airdrop and asked for the armistice announcement to be postponed. Angered by the Italian dithering, Eisenhower agreed to abandon the airdrop but refused to accept a cancellation of the announcement. Kesselring didn’t know this detail but assumed General Taylor’s presence in Rome meant that an Allied airdrop around Rome was imminent. He told Dollmann that if Allied paratroops landed, the goal of securing Rome was lost.

Kesselring knew he had to act fast. He began by attempting to block all the entry points into Rome. When the King and Badoglio heard of the Germans’ intentions they too acted quickly. In darkness, clutching a few of their possessions, the royal family, along with Badoglio and his ministers, fled the city.

No orders were left with the army and no one was given military command. As dawn broke on 9 September, Rome was at the mercy of the Germans.

Over the course of the day gunfire could be heard across the city as pockets of Italians made up of soldiers and civilians began to resist the German troops who were edging their way towards the centre of Rome. The resistance was patchy and uncoordinated. Some of the Italians were bedraggled and appeared to be hungry, and many had no ammunition. The Germans had the upper hand militarily and tactically. On 10 September the battle for Rome entered its final phase.

With the city under siege, Hugh O’Flaherty and Sir D’Arcy Osborne could only watch and wait as they stayed in the Vatican. They could see and hear the sounds of battle, and for the moment they were like prisoners of war themselves.

The Pope was now seriously worried that the Germans would first take Rome and then move into the Vatican. He told his staff to keep their suitcases packed and then asked Cardinal Maglione to contact the German Ambassador to the Vatican, Baron Ernst von Weizsäcker, for some clarification. Maglione asked him if the Germans would respect the neutrality and extra-territorial status of the Holy See’s property. As gun battles continued across the city, Weizsäcker contacted his masters in Berlin and the Pope had to bide his time.

By now German ‘Tiger’ tanks were moving through the streets and the last lines of resistance were being overcome. The initial unease felt in the Vatican had now turned to panic. Everyone in the Holy See was on full alert. In an unprecedented move, St Peter’s Basilica was closed off and the gates to the Vatican City were shut. The Swiss Guards, who normally patrolled with ornamental pikes, were issued with firearms.

The Pope had good reason to seal off the Vatican City, as he wished to keep the whole site immune from the chaos that was engulfing Rome. Across the city there was fear and uncertainty. Burglaries, assaults, rape and murder had spread to all districts as Romans took matters into their own hands. But Friday night was their last evening of unrestrained lawlessness. By the following evening the city was swarming with SS men, infantrymen and German troops of all descriptions. The battle was over and as darkness fell Rome had new rulers.

Field Marshal Kesselring declared martial law and his ten-point proclamation was pasted on walls throughout the city. His decree stated that Rome was under his command and all crimes would be judged according to German laws of war. He also made it clear that snipers, strikers and saboteurs would be executed. All private correspondence was prohibited and all phone calls would be monitored.

That night, at the Wolf’s Lair, Hitler recorded a special broadcast which was transmitted shortly afterwards on Radio Rome. His delight at having captured the Italian capital was obvious, though it was punctuated with a series of warnings and he declared that Italy would suffer for deposing its once-favourite son. Clearly Mussolini was on the Führer’s mind. Hours later the mission to rescue him from the heights of the Gran Sasso began.

The Nazi high command had also become worried that the intelligence work and planning organized before the Italian surrender would go to waste. Even during the battle for Rome, Himmler had sent a message to Captain Skorzeny and General Kurt Student, the commander of Germany’s airborne forces, reminding them that Mussolini’s rescue was still a top priority. Both men concluded there were three ways to carry out the rescue. They could arrive at the Gran Sasso by parachute, perform a landing by glider, or launch a ground attack.

On the afternoon of Sunday, 12 September a group of gliders carrying German paratroops made their way to the remote mountain resort. Mussolini was sitting by the window in his room and saw Skorzeny’s glider crash land outside the hotel. The young captain climbed out and ran towards the building. He overpowered a radio operator and bundled a number of carabinieri out of the way. He climbed the stairs and on the second floor turned right. Moments later he found himself face to face with the man he had been hunting for six weeks, Benito Mussolini.

Skorzeny spoke first. ‘Duce, the Führer has sent me to set you free.’

‘I knew my friend Adolf Hitler would not abandon me,’ Mussolini replied.

By now the other paratroops had secured the building and the cable car, and the underground passage that linked the hotel and the resort’s station was in German hands. The kidnapping had taken its toll on Mussolini: he looked tired and ill and a little unkempt. Wearing an oversize overcoat and a felt hat, he walked out of the hotel and his every movement was tracked by a German newsreel cameraman who had come along to record the rescue. He made his way to one of the gliders and then, tucked behind the cockpit, he sat beside Skorzeny.

The take-off from the mountaintop nearly ended in disaster. The glider shot down into a chasm but the pilot was able to pull out of the nose-dive. An hour later they landed safely and then Mussolini and Skorzeny were put on another plane. Aboard the Heinkel 111, they were flown for an overnight stay in Austria. Back in Rome Herbert Kappler was anxiously waiting for news and when it came he quickly passed it on to officials in Berlin. Shortly after six o’clock he cabled a message informing them that the rescue of Mussolini had been carried out successfully and that a meeting had been arranged with senior officers in Vienna.

The next day Skorzeny and Mussolini were due to fly to Munich, where the former dictator would meet up with his wife.

Before he retired to bed Skorzeny received a telephone call. It was Hitler, who told the young captain, ‘Today you have carried out a mission that will go down in history and I have given you the Knight’s Cross and promoted you to Sturmbannführer.’

The Führer was thrilled that Mussolini had been freed and he was clearly in the mood to congratulate those who had helped in the rescue mission. After Skorzeny was honoured, there were others to be recognized. Herbert Kappler was also on the list and he was given the Iron Cross for his work. However, for him there was another reward to come. He was promoted to Obersturmbannführer, the highest rank of his career. Five weeks earlier he had been ordered to stay in Rome by the Führer and told to concentrate on police intelligence work. Now, with the city in German hands, Lieutenant Colonel Kappler had an even bigger job to do.