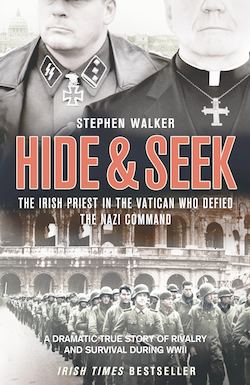

Читать книгу Hide and Seek: The Irish Priest in the Vatican who Defied the Nazi Command. The dramatic true story of rivalry and survival during WWII. - Stephen Walker - Страница 7

ОглавлениеChapter Three ROME IS HOME

‘I don’t think there is anything to choose

between Britain and Germany’

Hugh O’Flaherty

On a fairway at Rome Golf Club, the Japanese Ambassador could only watch with amazement and a little envy as his opponent’s ball arced high and long and then landed close to the green. The tee-off was textbook. It was perfect, a wonderful drive that set up the second shot beautifully. It was 1928 and this was the diplomat’s farewell game, a last chance to enjoy eighteen holes in the company of friends before returning to Tokyo. And it was not going according to plan. He was playing a man who had a lifetime of practice that had begun on the greens of Killarney. It was a rather one-sided contest. The monsignor was in fine form and clearly relishing the day a little more than his playing partner.

At the picturesque club, sited on grassland outside Rome, Hugh O’Flaherty’s golfing skills were often the topic of conversation. To some the gifted player seemed unconventional. He didn’t dress like a golfer, sometimes wearing grey trousers and a favourite orange jumper, and his unusual grip was frequently the butt of jokes. ‘Why don’t you hold the club like any other human being?’ one player teased him, remarking that the monsignor seemed to grip the golf club rather like the stick used in hurling, a sport favoured by O’Flaherty’s countrymen.

The priest was very capable of taking the banter and shot back a detailed reply. ‘For the correct grip in hurling, the left hand is held below the right. I am holding my golf club just the opposite, my right hand is below the left,’ he explained with a smile on his face to all those present.

The technicalities were probably lost on his opponents but his ability to play and win the game wasn’t. His continued success on the greens meant that he had to concede a couple of shots to less able players. The par for the course was seventy-one and O’Flaherty regularly came close to that.

His fellow players also wondered how a busy priest weighed down with church duties had time to play golf. For O’Flaherty it was an opportunity to relax and forget the cares and worries of the job. He told a friend that there was ‘nothing like golf for knocking all the troubles of this poor world out of your mind’.

Even though he loved the game, there were times when the distance he had to travel and the price of playing seemed too high. In a letter home he wrote, ‘The links are far from the city and, besides, to be a member one must know how to rob a bank and keep what is robbed.’ Despite his reservations about spending hours driving, chipping and putting, there were other benefits to his favourite pastime. The club had a very influential membership and O’Flaherty began meeting many leading members of Roman society – including royalty, aristocrats, diplomats and politicians – who would prove useful to his escape network.

Those who regularly played the course included Count Galeazzo Ciano, who was married to Mussolini’s daughter Edda. Ciano was the Italian Foreign Minister and O’Flaherty is credited with teaching him the finer points of the game. Another regular player at the club was the former King of Spain, Alfonso.

It was on the golf course that the monsignor was introduced to Sir D’Arcy Osborne. Like O’Flaherty, the British diplomat loved nothing more than taking the Italian air with his clubs on his back. The game was part of Osborne’s life; so much so that he often used golfing references in his correspondence. Exasperated by the intransigence of a position taken by the powerful of the Vatican, he once wrote that trying to get them to change their mind was like ‘trying to sink a long putt using a live eel as a putter’.

With a direct line to the Papacy, Osborne was one of the most influential people in Rome. He was the image of the English gentleman: well-mannered, charming and courteous. A bachelor, he was tall and slim and always immaculately dressed. As a career diplomat he was highly regarded in London and as a cousin of the Duke of Leeds he was well connected and counted the Duke and Duchess of York as friends.

Osborne had a deep affection for Italy, a country he had first visited at the turn of the century, when he had been won over by the people and the scenery. He joined the diplomatic service and after postings in Washington, Lisbon and The Hague he became Britain’s Minister to the Holy See in 1936. He spoke Italian and French and loved art, expensive shoes and fine wine. Like all those who occupied the position of ambassador to the Vatican, he was a Protestant, in case there was a conflict of loyalties. Given O’Flaherty’s Irish nationalist background and Osborne’s British establishment credentials, the pair were an unlikely match. Yet over time they became good friends and would meet both in the club house and at the Vatican.

In the early weeks of the Second World War Osborne’s knowledge and diplomatic skills were much in demand. There was a fevered debate about when Italy would enter the conflict and much concern in Vatican circles over how this would affect its protected status. As Britain’s representative to the Vatican, Osborne’s views were sought by the leaders of the Catholic Church and he was used to test ideas and opinions.

In the spring of 1939 a new resident was holding court in the Vatican’s Apostolic Palace. On 2 March Cardinal Eugenio Pacelli had become Pope on his sixty-third birthday. In one of the shortest conclaves in the Church’s history he was elected by sixty-two cardinals. The first Roman-born Pope in over 200 years, Pacelli took the name of Pius XII, in honour of his predecessor Pius XI.

The new Pontiff had had little time to settle into office when, on 15 March, the Germans entered Prague. Over the next few months papal envoys would become involved in shuttle diplomacy with Mussolini, Hitler and the Polish and French governments in a bid to avert war. The discussions did not succeed. On 1 September 1939 Hitler invaded Poland, and two days later Britain and France declared war on Germany.

In his office in Rome Kappler had begun to gather information from all over the city on both anti-fascists and under-cover agents he could employ. He was watching the new regime of Pius XII with particular interest as he wanted to recruit informers within the Vatican. But, before he could make much progress, he was instructed to return to Germany.

Two incidents had occurred, just hours apart, which would focus attention on Hitler’s leadership; events which required the skills of Herbert Kappler. These two investigations would not only enhance the police attaché’s reputation but bring him into direct contact with the Führer. When Kappler arrived in Berlin there was only one story occupying the minds of the Nazi leadership. Days earlier, in a Munich beer hall, Hitler had acknowledged the adoring crowds as he stood in front of a swastika-draped stage. Hundreds of supporters had come to hear the Führer speak at an annual get-together for the Nazi Party’s old guard. At 9.07 p.m. he finished his speech, earlier than planned, and left the building. Hitler had planned to fly back to Berlin, but poor weather made this impossible and he was taken to the railway station instead.

The decision to change his travel plans saved Hitler’s life. At 9.20 p.m. a bomb, hidden in a pillar close to where he had been speaking, exploded. The ceiling and balcony collapsed, killing eight people and injuring many others.

As Hitler made his way back to Berlin, German police held in custody a 36-year-old carpenter from Württemberg who had been arrested as he tried to leave the country and enter Switzerland. Georg Elser had travelled by train from Munich and had been spotted trying to cross over at the border town of Konstanz. A trade unionist and an opponent of Nazism, he had first gone to Munich a year earlier to observe the Führer deliver his annual speech at the Burgerbräukeller. Over the next twelve months the carpenter planned his attack for the following year’s event at the beer hall. He became a regular diner there and over time he built a bomb which he would eventually place in a pillar close to the hall’s podium. As anticipated, on 8 November Hitler was to deliver a speech in the Burgerbräukeller in the evening and Elser had timed the device to go off at around 9.20 p.m.

Shocked at how close someone had come to killing the Führer, the Nazi high command handed the investigation over to the Gestapo. When Kappler arrived in Berlin he was assigned to be part of the team interrogating Elser, who initially had refused to say anything. The police attaché had been in this position many times before: in Austria he had interrogated anti-Nazi dissidents and in Rome he had begun the same work. Now, as he sat opposite Elser, his main job was to break the man’s silence.

Elser was bombarded with questions. How did he prepare the bomb? When did he go to Munich? But perhaps most interesting for Kappler and his Gestapo colleagues was the question of who had helped the carpenter. They began to track down anyone who knew Elser and had been in contact with him in recent months. Investigators caught up with Else Stephan, Elser’s girlfriend, who was questioned personally by Himmler and then taken to Hitler. Of the latter encounter she later said, ‘Behind a table sat a man in a field-grey uniform. He didn’t look up when one of the SS men reported: “My Führer! This is the woman!” Good Lord, it really was Hitler. Hitler put down a folder he had been reading and looked at me. He didn’t say anything. I felt most embarrassed. I wanted to salute but I just couldn’t raise my arm.’

Hitler looked at his visitor for a while before speaking. Then he said, ‘So you are Elser’s woman. Well, tell me about it.’ Else Stephan told Hitler her story just as she had done with Himmler, who was in charge of the investigation. Eventually, after Elser was beaten, investigators secured a confession. Postcards from the Burgerbräukeller had been found in his coat and one of the waitresses recognized him as a regular customer.

Elser was then tortured by the Gestapo, who initially found it difficult to accept that the carpenter had acted alone. Hitler himself was convinced that he had been helped by British Secret Service agents. Under questioning Elser insisted that he had carried out the operation without any help. Himmler personally took part in a number of the interrogations and on one occasion told the suspect, ‘I’ll have you burnt alive, you swine. Limb by limb quite slowly … do you understand?’

Kappler would maintain in an interview some years later that he treated Elser properly during the interrogations. ‘I always spoke to Elser very calmly. He opened up to me without reservation. And I also had the impression that he was telling us the truth on all points – and this was corroborated when his statements were checked.’

Elser made a confession that ran to hundreds of pages. He would be imprisoned at Sachsenhausen and Dachau concentration camps, remaining at the second until the final weeks of the war, when he was taken from his cell and killed. The American forces were nearby but with the war about to end the German high command clearly had some old scores to settle.

Back in 1939, hours after Elser’s arrest, Kappler would find himself examining another ‘plot’ to topple Hitler. This one, bizarre and complicated, did involve Britain’s Secret Service at the highest level.

It began one winter’s morning and involved two British intelligence agents and one Dutch. Before dawn, Sigismund Payne Best was awake. A man in his fifties, he headed Britain’s highly secretive Section Z in the Netherlands. He got up and as he shaved he thought of what lay ahead over the next few hours, and he was nervous. He had reservations but knew he had little choice. He kissed his wife goodbye, told her he might be late, then hurried to his office. There he glanced at the morning paper. A stop-press item about the attempt on Hitler’s life in a beer hall caught his eye. It reported how the Führer had escaped but others had been killed. Best then headed to meet some colleagues, all the time wondering if the incident in Munich he had just read about had anything to do with a group of German officers he had recently become acquainted with.

Payne Best called at a house to pick up two colleagues. Richard Stevens, a less experienced British intelligence officer likewise based in The Hague, was an agent with whom he had recently begun working. The other man was Dirk Klop, who had been seconded from the Dutch intelligence service. The three men chatted about the day ahead and Stevens produced loaded Browning automatic pistols which they each pocketed. Then, as storm clouds gathered, they made their way to the border with Germany.

In the cold November air they arrived at Café Backus, an eating house near the Dutch town of Venlo, close to the border with Germany. The men were familiar with the building, which was of red brick with a veranda and at the back had a large garden with children’s swings.

The venue for the meeting had been carefully chosen. It was in the Netherlands, but stood in a stretch of land between the German and Dutch customs posts. Best, Stevens and Klop had come to the border to continue discussions with high-ranking Nazi officers who wanted to overthrow Hitler. In previous meetings the trio had been told that there was support for Hitler’s removal and the restoration of democracy, which would lead to an Anglo-German front against the Soviet Union. In London senior military officials and politicians including the Prime Minister were kept informed about the discussions. The story had one problem. It was not true. The British and Dutch intelligence officers had been duped as part of a ‘sting’ organized by the German intelligence service.

Best and Stevens had been dealing with an officer named Major Schämmel, who claimed to be a member of an anti-Hitler plot. Schämmel was in fact Walter Schellenberg, a rising star in the world of German military intelligence who would later become the head of the SS’s foreign-intelligence section.

When the three agents arrived at the café the scene was peaceful. A little girl was playing ball with a dog in the middle of the road and nearby a German customs officer was standing watching for traffic. However, this time something seemed different. When they had been to the café before, the barrier to the German side had been closed, but they now noticed that it had been raised. Best sensed danger. As they drove into the car park their contact Schämmel spotted them and waved at them from the veranda. At that moment a large car came from the German side of the border and drew up behind the visitors. Within seconds shots were fired in the air and the two Britons, Dirk Klop and their driver were surrounded by German soldiers and ordered to surrender.

Stevens turned to his colleague and said simply, ‘Our number is up, Best.’ They would be the last words the pair would exchange for five years.

Within hours they were in Berlin and Herbert Kappler had more interviews to conduct. The so-called Venlo incident was a coup for German military intelligence and a source of embarrassment for the British government. The Germans had captured senior British intelligence figures and their removal from clandestine activities was also a crucial blow to British espionage efforts across Europe. Kappler remained in Berlin to help in the interrogation of Best and Stevens. The pair were questioned at length and were later imprisoned at Sachsenhausen and Dachau, where Best reportedly came into contact with Hitler’s would-be assassin Georg Elser.

The Elser affair kept the issue of Hitler’s leadership in the headlines and stories about plots and coups against the Nazi leader continued to surface. When Kappler returned to Rome to resume his duties as police attaché there, Hitler’s future was a subject that was dominating the chatter among the city’s diplomatic circles.

In January 1940 Sir D’Arcy Osborne was called to meet Pope Pius for a private audience. The pair discussed the war and considered a series of scenarios. The Pope claimed he knew the names of German generals who said that Hitler was planning an offensive through the Netherlands in the weeks ahead. He said this need not happen if the generals could be guaranteed a peace deal by the Allies that would see Hitler deposed, and in return Poland and Czechoslovakia would be free of German rule. The Pope was nervous and asked Osborne to keep the contents of the discussion secret, telling him, ‘If anything should become known, the lives of the unnamed German generals would be forfeit.’

Osborne refused the Holy Father’s request and reported the contents of the encounter to officials in London. In his official report the Minister to the Holy See wrote that he thought the discussions had been vague and reminded him of the Venlo incident. His words carried extra weight because the arrest of the three British intelligence officers was still an embarrassment to many in London.

The following month Osborne again met the Pope, who told him that, according to information he had been given by prominent German generals, Hitler was planning to invade Belgium. As he had done before, the Pope talked about a potential uprising against the Führer in Germany. He suggested that there could be a civil war and a new anti-Hitler government might have to start as a military dictatorship. Again the Pope wanted to know what, if the Führer was overthrown and a new regime was put in place, would be the basis of negotiations with the Allies.

The Pope insisted that these details be kept to a small number of people. He agreed, however, that Osborne could mention them in a letter to Lord Halifax, the Foreign Secretary, in the hope that this would have a limited readership. The Pope’s obsession with secrecy was understandable. Everyone was being watched. Every visitor was recorded, every meeting noted. Osborne’s daily habits were routinely logged and the details were stored at the headquarters of the Italian secret police. The Vatican was also in the sights of the German police attaché, who was now recruiting informers across the city to spy on the occupants of the Holy See. Although Italy had yet to officially declare hostilities against the Allies, in Rome an intelligence war was well underway. Caught up in this battle, the Pope knew that a diplomatic process had to be maintained and at the same time was determined that nothing would threaten the status of the Catholic Church. To protect the Church’s interests, he kept lines of communication open with both the Allies and the Germans.

Under the Lateran Treaty of 1929 the Vatican was guaranteed independence. This accord between the Holy See and the Italian state established diplomatic conventions as well as agreements on physical access. Italy recognized the 108-acre site, which included the Vatican and St Peter’s, as an independent sovereign state. The agreement also covered fifty acres outside the Vatican walls and gave protected status to a number of extra-territorial buildings, including three basilicas and Castel Gandolfo, the Pope’s country retreat. The accord made the Vatican City the smallest state in the world. In response the Holy See recognized Rome as the capital of the Italian state and pledged to remain neutral in international conflicts. The Pope was not allowed to interfere in Italian politics. While he felt entitled to speak out in general terms about the war, he was worried that his private discussions with Sir D’Arcy Osborne would become public and his role could be misinterpreted.

By the early summer of 1940 some of the Pope’s predictions had come true and, although the overthrow of Hitler by his generals did not happen as expected, the Germans had arrived in the Low Countries that May. A month later, despite a plea from Britain’s Prime Minister Winston Churchill, Benito Mussolini declared war on the Allies. The move would have an immediate personal effect on Sir D’Arcy Osborne. Could he continue to stay in Rome as a British representative while Italy was now at war with Britain? The Vatican solved the predicament and informed the Italian government that it could offer lodgings for diplomats within the Vatican City. As a neutral state, the Vatican could allow ambassadors and other diplomats to reside on its territory.

Back in London, Osborne’s bosses were worried that, although a move into the Vatican would enhance his personal safety, it might make communication between London and Rome more difficult. They offered him the use of a secret radio transmitter. Aware of the dangers of being caught and how such activity would compromise his new hosts, he declined the offer. Three days after Mussolini’s declaration of war, Osborne took down the British coat of arms at his office, gathered up his belongings and furniture, and moved to a pilgrims’ hostel on the south side of St Peter’s, inside the Vatican. He was to be housed temporarily in an annexe of the Santa Marta Hospice known as the Palazzina. There he was given four rooms. He took with him his typist Miss Tindall, his butler John May and his cairn terrier Jeremy. Osborne was now in a new environment, a tiny enclave shut off from the immediate dangers of war, a place where he clearly felt safe.

His temporary home was eventually transformed and at vast expense a new kitchen, bathroom and lavatory were installed. Osborne made himself comfortable, putting up paintings, portraits of the royal family, and maps of western Europe to plot the progress of the war. For the next four years this would be the headquarters of the British Vatican envoy. Sir D’Arcy Osborne and Hugh O’Flaherty were now neighbours. Theirs was a relationship which would be crucial to the operation of the Allied Escape Line.

Osborne’s new address placed him high on the list of the Italian secret police. They put him under surveillance and wanted to know if he was spying for British intelligence or passing on messages to anti-fascists in Italy. The British envoy knew he was being watched and he recorded his thoughts: ‘I believe that daily reports are sent out on our doings. They must be damned dull reading.’

As it did for Osborne, the war would have a profound effect on O’Flaherty’s daily life. While hostilities continued across Europe, the monsignor’s official job in the Holy Office started to change. By 1941 tens of thousands of Allied servicemen were being held in prisoner of war camps across Italy. The Vatican accepted that it was important that the POWs’ welfare was routinely checked to ensure they were being held in accord with international conventions. Pope Pius wanted two of his officials to visit the camps regularly. He appointed Monsignor Borgoncini Duca as his Papal Nuncio and, needing an English speaker to deal with the British prisoners, he asked Monsignor O’Flaherty to act as Duca’s secretary and interpreter. The Pope’s decision changed O’Flaherty’s life.

The monsignor would develop empathy for prisoners and would become more sympathetic to the Allied cause.

Duca and O’Flaherty began to travel around the country together, but they took very different approaches to the job. Duca was more relaxed and seemed unhurried and when he travelled by car he usually managed to see only one prison camp a day. O’Flaherty used his time differently. He accompanied the Papal Nuncio to the camps, but in the intervals between visits he would return to Rome on the overnight train. Once back in the capital he would pass on messages from prisoners to Vatican Radio to ensure that their relatives knew they were safe. The monsignor also speeded up the delivery of Red Cross parcels and clothing and helped in the collection of thousands of books for the prisoners.

O’Flaherty’s work clearly improved the morale of the POWs, but he did more than supply them with creature comforts. He became their champion, a significant move for a man who in his youth had little good to say about those who wore the uniform of the British Army. The monsignor began to lodge complaints about the way the men were being treated and his protestations led to the removal of the commandants at the hospitals at Modena and Piacenza. He also visited South African and Australian prisoners at a camp near Brindisi. There he distributed musical instruments including mandolins and guitars. Much to the annoyance of the prison’s management, the trip boosted the morale of the inmates and lowered that of their captors.

By now the monsignor was seen by the Italian military’s high command as a troublemaker. Pressure was exerted on the Vatican to remove him and eventually O’Flaherty resigned his position. Officially the Italian authorities claimed that the monsignor’s neutrality had been compromised. They said he had told a prisoner that the war was going well. It was a feeble excuse. Unofficially they wanted him out of the way because he was exposing the mistreatment of prisoners.

His visits to the prison camps made O’Flaherty increasingly aware that more needed to be done to help those who were suffering during the war. He may not have realized it at the time, but it seems likely that his meetings with Allied POWs helped to crystallize his thinking. When hostilities had first begun across Europe, he had viewed the conflict as an independent neutral observer, deliberately refraining from taking sides. He had always felt that both the Allies and the Germans were guilty of propaganda and he didn’t know what to believe. He had even once remarked, ‘I don’t think there is anything to choose between Britain and Germany.’

Now, as the war came ever closer to the streets of Rome, Hugh O’Flaherty discovered where his loyalties lay.