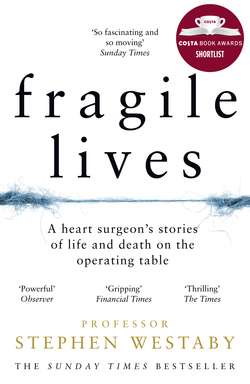

Читать книгу Fragile Lives: A Heart Surgeon’s Stories of Life and Death on the Operating Table - Stephen Westaby, Stephen Westaby - Страница 17

the girl with no name

ОглавлениеDream that my little baby came to life again, that it had only been cold, and that we rubbed it before the fire and it had lived. Awake and find no baby.

Mary Shelley, author of Frankenstein

The girl was hauntingly beautiful, with eyes that burned like lasers – as if the blistering desert heat were not enough (50°C during the day). When she fixed those eyes on mine she delivered a message – eye to eye, pupil to pupil, retina to retina – straight into my cerebral cortex. As she stood there holding her bundle of rags I understood perfectly what she was saying: ‘Please save my child.’ But she never spoke. Not to any of us. Ever. And we never even knew her name.

The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, 1987. I was young and fearless, seemingly invincible and massively overconfident, and had just been appointed as a consultant in Oxford. So why was I in the desert? Heart operations cost money. We’d worked hard to build Oxford’s new cardiac centre and clear a backlog of sick hearts, but the annual budget was gone in five months so the management closed us down. Bugger the patients. The cardiologists were told to send them to London again.

On the day before I was locked out of the operating theatre I took a call from a prestigious Saudi cardiac centre that served the whole Arab world. Their lead surgeon needed three months sick leave, and they were looking for a locum who could tackle both congenital and adult heart surgery, an extremely rare species. At the time I wasn’t interested but the following day I was, and three days later I jumped on the plane.

It was Jumada al-thani, the ‘second month of dryness’ in the Middle East, and I’d never felt heat like it, blistering, unremitting heat with the hot shamal wind blowing sand into the city. But it was a great cardiac centre. My medical colleagues were an eclectic mix of Saudi men who had trained overseas, Americans rotating from the major centres for experience, then the band of mercenaries from Europe and Australasia.

Nursing was very different. Saudi women did not nurse, as the profession was regarded with suspicion and disrespect, and was culturally taboo because it required mixing with the opposite sex. So all female nurses were foreign, most with contracts for just one or two years. Their accommodation was free, they paid no tax and stayed just long enough to save for that elusive mortgage back home. In turn they were not allowed to drive, had to travel in the rear of buses and be completely covered in public.

I was intrigued by my new environment: the repetitive calls to prayer from the minarets, the tantalising aromas of sandalwood, incense and amber around the hospital, Arabian coffee roasting on the frying pan or boiling with cardamom. It was a very different life and important not to step out of line – their culture, their rules, harsh penalties.

This presented a unique opportunity for me as I could operate on every conceivable congenital anomaly. There were innumerable young patients with rheumatic heart disease sent from remote towns and villages, mostly without access to anticoagulant therapy or drugs that we take for granted in the West. The rural health care was out of the Middle Ages, and we had to innovate and improvise to repair their heart valves rather than replace them with prosthetic materials. I remember thinking that every cardiac surgeon should train here.

One morning a bright young paediatric cardiologist from the Mayo Clinic, the world-famous medical centre in Minnesota, came to find me in the operating theatre. His opening gambit was, ‘Can I show you something really interesting? Bet you haven’t seen anything like this before,’ swiftly followed by, ‘Sadly, I doubt you can do anything about it.’ I was determined to prove him wrong even before I’d seen the case because for surgeons the unusual is always a challenge.

He thrust the X-ray onto a light box. On a plain chest X-ray the heart is simply a grey shadow, but to the educated eye it can still tell the story. The message was clear. This was a small child with an enlarged heart in the wrong side of the chest, a rare anomaly called dextrocardia. Normal hearts lie to the left. In addition there was fluid on the lungs. But dextrocardia alone does not cause heart failure. There had to be another problem.

The enthusiastic Mayo cardiologist was testing me. He had already catheterised the eighteen-month-old boy and knew the answer. I offered an insightful guess to show off – ‘In this part of the world it could be Lutembacher’s syndrome.’ This is a dextrocardia heart with a large hole between the right and left atrium, together with rheumatic fever that narrows the mitral valve, a rare combination which floods the lungs with blood, leaving the rest of the body short. The Mayo man was impressed. But no cigar!

He then wanted to take me to the catheterisation laboratory to see the angiogram (moving X-ray pictures with dye shot into the circulation to clarify the anatomy). By now I’d become fed up with the quiz but I still went along with him. There was a huge, sinister mass within the cavity of the left ventricle below the aortic valve, almost cutting off the flow of blood around the body. I could see this was a tumour, and whether benign or malignant the infant could not survive for much longer. So could I remove it?

I’d never seen surgery on a dextrocardia heart before. Few young surgeons had and most never would, but I did know about heart tumours in children. Indeed I’d published a paper on the subject in the United States that the paediatric cardiologist had read, making me the expert on the subject in Saudi Arabia.

The most common tumour in babies is a benign mass of abnormal heart muscle and fibrous tissue called rhabdomyoma. This is often associated with a brain abnormality that causes epileptic fits. No one knew whether the poor boy had suffered fits, but he was certainly dying from an obstructed heart. I asked the boy’s age and whether his parents understood the desperate nature of the condition. Then his tragic story began to unfold.

It happened that the boy and his young mother were close to death when the Red Cross found them on the border between Oman and South Yemen. In the searing heat both were emaciated, dehydrated and in a state of collapse. Apparently she’d carried her son through the desert and mountains of Yemen, frantically seeking medical help. They were airlifted to the Military Hospital in Muscat in Oman, where they’d found that she was still trying to breastfeed. She’d nothing else to feed her son but her milk had dried up. When the boy was rehydrated with fluids into a vein he became breathless and was diagnosed with heart failure. In turn the mother had severe abdominal pain and a high temperature from a pelvic infection.

Yemen was a lawless place. She’d been raped, abused and mutilated. Not only that, she was African, not an Arab. The Red Cross suspected that she’d been kidnapped from Somalia and taken across the Gulf of Aden to be sold as a slave. But for one curious reason they couldn’t be sure. She never spoke. Not a word. And she barely showed any emotion, even in response to pain.

When the Omanis saw the boy’s chest X-ray and diagnosed dextrocardia and heart failure they transferred him to our hospital. Now, the Mayo man wondered whether I could conjure up a miracle. I knew that the Mayo Clinic had a great children’s heart surgeon so I tentatively asked my colleague what Dr Danielson would do.

‘Operate, I guess,’ he said. ‘Not a lot to lose, as it’s all downhill from here.’ That’s what I expected him to say.

‘Right then, I’ll do what I can,’ I said. ‘At least we’ll know what kind of tumour it is.’

What else did I need to know about the boy? Not only was his heart in the wrong side of the chest, but the abdominal organs were switched over too. What we call situs inversus. So the liver was in the left upper quadrant of the belly with the stomach and the spleen on the right. The bigger problem was that there was a large hole between the left atrium and right atrium, so blood returning from both the body and the veins of the lungs mixed freely. This meant that the level of oxygen in the arteries to his body was lower than it should be. Had his skin not been black he may have been recognised as a blue baby, where blood in the veins streams across into the arteries. Complicated stuff, even for doctors.

Money was no object here. We had state-of-the-art echocardiography, which in those days was new and exciting. It employed the same ultrasound waves that were used to detect submarines underwater, and an accomplished operator could provide sharp pictures of the inside of the heart and measure pressure gradients across areas of obstruction. I saw a clear image of the tumour in the small left ventricle, smooth and round, like a bantam’s egg, and felt confident that it was benign. If only I could relieve him of it, the tumour would not grow back.

My plan was to clear the obstruction and close the hole in the heart, an ambitious attempt to restore normal physiology. This was straightforward in principle yet taxing in a back-to-front heart in the wrong side of the chest, and I didn’t want any surprises. So I did what I always do in difficult circumstances – set about to draw the anatomy in detail.

Was the surgery possible? I didn’t know, but we had to try. Even if we failed to remove the tumour completely it would still help him, although should it prove to be a rare malignancy his outlook would be bleak. But between us we were convinced that it was a rhabdomyoma.

It was time to meet the boy and his mother. Mayo man took me to the paediatric high-dependency unit where he was still being fed via a tube through his nose, which he disliked intensely. His mother was sitting cross-legged on a mat on the floor beside the cot and she never left his side, day or night.

As we approached she rose up. She was not at all what I’d expected – stunningly beautiful, with a striking resemblance to the model Iman, the widow of David Bowie. Her jet black hair was straight and long, her skinny arms folded across her chest. The Red Cross had established that she was Somali, and as she was a Christian her head was not covered.

Her long delicate fingers were clutching the bundle in which she held her son, precious rags that had shielded him from the hot sun then kept him warm in the cold desert nights. An umbilical cord of drip tubing emerged from these swaddling clothes and stretched to the drip pole and a bottle of feed, which was a milky-white solution replete with glucose, amino acids, vitamins and minerals to put meat back on his little bones.

Her eyes turned towards the stranger, the English heart surgeon whom she had heard about. Head gently tilted backwards in an attempt to remain detached, a bead of sweat appeared in the root of her neck and slithered down over the sternal notch. She was becoming anxious and her adrenaline was flowing.

I tried to engage with her in Arabic. ‘Sabah al-khair, aysh ismuk?’ (Good morning, what’s your name?). She said nothing and looked at the floor. Showing off, I continued, ‘Terref arabi?’ (Do you know Arabic?), then, ‘Inta min weyn?’ (Where are you from?). Still no response. Finally in desperation I asked, ‘Titakellem ingleezi?’ (Do you speak English?). ‘Ana min ingliterra’ (I’m from England).

Then she looked up, wide eyed, and I knew that she understood. Her lips parted but still no words. She was mute. Mayo man was speechless too, stunned by my linguistic skills, which unbeknownst to him had almost been exhausted. She appeared to appreciate my efforts and her shoulders dropped. She relaxed. I wanted to show her kindness, to take her hand, but I couldn’t in this environment.

I indicated that I’d like to examine the boy, which was fine as long as she could continue to hold him. But I was shocked as she pulled back his linen covering. The lad was emaciated, with all his skinny ribs protruding. There was virtually no fat on him and I could see his bizarre heart pounding against his chest wall. He was breathing rapidly to overcome the stiffness in his lungs, his protuberant belly full of fluid and his enlarged liver clearly visible on the opposite side to normal. From the different skin tone to his mother I assumed that his father was an Arab. A curious rash covered his dark olive skin and I thought I saw fear in his eyes.

His mother pulled the linens back over his face, protectively. He was all she had in the world, this boy and a few rags and rings, and I couldn’t help the upwelling of pity I felt for both of them. Surgery was my business but I was sucked into this whirlpool of despair, my objectivity gone.

In those days I had a red stethoscope and I placed it on the infant’s chest, trying to look professional. There was a harsh murmur as blood squeezed past the tumour and out through the aortic valve, then the crackling sounds of wet lungs, even the gurgling and bubbling of empty guts. The cacophony of the human body.

Next I said, ‘Mumken asaduq?’ (‘Will you let me help you’?). For a second I thought she responded. Her lips moved and those eyes fixed on mine. I sensed that she’d murmured, ‘Naam’ (Yes). I tried to explain that I needed to operate on the boy’s heart to make him well so they could both have a better life. When tears appeared in her eyes I knew that she understood.

But how could I persuade her to sign a consent form? We sent for a Somali interpreter who repeated my words, yet still we had nothing in return. She remained impassive as I struggled to convey the complexities of the surgery. Name of the operation: ‘Relief of left ventricular outflow tract obstruction in dextrocardia’. Then a short sentence for my own benefit: ‘High risk case!’ Absolving me of any blame, on paper at least. I was confident that this was the boy’s only chance of survival, so just an ‘X’ from the mother would be enough. But she was signing over her whole life, her only reason for living. Eventually she took the pen from my hand and scribbled on the form, then I asked Mayo man to countersign and I signed it myself, looking directly into her eyes not at the document, searching for approval, I guess. By now her skin was glistening with perspiration; she was pouring out adrenaline and trembling with anxiety.

It was time for us to leave her alone. I indicated that I’d do the operation on Sunday when the best paediatric anaesthetist was available, then I said goodbye in both English and Arabic to show that I was still making an effort.

This was Thursday afternoon, the day before the Saudi weekend, and my colleagues were planning to take me out to the desert to camp on the dunes beneath the night sky as a way of escaping the oppression of the city. The convoy left in the early evening, just as the searing heat was starting to abate. When we ran out of road, the jeeps ploughed through the sand, miles and miles of it. They had a rule – never travel in just one vehicle. If it broke down that could be the end, even within twenty miles of the hospital.

The desert night was clear and cold. We sat around the campfire drinking homemade hooch and watching shooting stars. A Bedouin camel train passed by silently barely two hundred yards away, swords and Kalashnikovs glinting in the moonlight. They didn’t even acknowledge us.

I felt uneasy and wondered how the mother had coped. Walking at night, hoping to find shelter during the day, and carrying water and child together, she must have been fuelled by hope but little else. However difficult it would prove to be, I was driven to save the boy and watch them both grow stronger.

The operation would be far from straightforward as I was still unsure of how to get at this tumour. The obstruction could only be accessible by opening the apex of the left ventricle wide, and that would impair its pumping ability. I kept working through the steps of the operation in my mind, always returning to the same question – ‘What if?’ With conventional surgery the technical challenges posed by this dextrocardia heart were virtually insurmountable. So would the boy be better off if he were operated on by a more experienced surgeon in the States? I couldn’t see why, because his combination of pathologies was probably unique. No one else would have greater experience, even if they did have a better team. I had a good enough team and great equipment, the best that money could buy. So I was the man for the job, wasn’t I?

It was then that I had my eureka moment, while staring up at the Milky Way. I suddenly knew the obvious way to get at the tumour. It might have been an outrageous idea, but I had a plan.

On Saturday I brought the anaesthetic and surgical teams together to discuss the case, and showed them the novel pictures of the unusual anatomy. Then, unusually – as much of what happens in an operating theatre remains impersonal, which is perhaps best when operating on those who may not survive – I told them the heart-rending story of the mother and boy. Everyone agreed that the boy was doomed if we made no effort but voiced justifiable concerns that the tumour was inoperable in dextrocardia. I said that we’d only know that through trying, although I kept the operating plan to myself.

I spent a hot, restless night in the apartment, my mind racing, disturbed by irrational thoughts. Would I have risked this back in England? And was I doing it for the patient or for the mother – or even for myself, so I could publish a paper about it? If I succeeded, who would care for this slave girl and her illegitimate child? The boy was an inconvenience. In Yemen he would be left out under a bush for the wolves to eat. It was the mother they wanted.

The early-morning call to prayer put an end to my discomfort. It was already 28°C as I walked from the apartment to the hospital. Mother and boy came down to the operating theatre complex and anaesthetic room at 7 am. She’d stayed awake until morning with her child in her arms, and all through the night the nurses had been concerned that she might capitulate and run away. She didn’t, but they were still worried whether she would hand the boy over.

Despite premedication he was screaming and thrashing around when they tried to put him asleep. Dreadful for the mother – and difficult for the anaesthetic staff – this was pretty much routine in paediatric surgery. Gas through the face mask eventually subdued him sufficiently to insert a cannula into a vein and stun him into unconsciousness. His mother still wanted to follow him into the operating theatre, so the ward nurses eventually dragged her away. Finally raw emotion had broken through the mask – whatever she had suffered physically, this was worse for her. Yet there were still no words.

I sat, dispassionate, in the coffee room until the mayhem abated, enjoying thick Turkish coffee and dates for breakfast. The caffeine hit was good for my ADHD but racked up my sense of responsibility. What if the boy dies? Then she has nothing. Nobody in the world.

One of the Australian scrub nurses came through to ask that I check the equipment, the extra bits I’d requested for the radical plan conceived under the dark desert sky. I’d yet to share it with my team.

Uncovered on the shiny black vinyl of an operating table, this emaciated little body was a pathetic sight, with none of the puppy fat that every infant deserves. Instead his skinny legs were swollen with fluid. The heart failure paradox – the muscle is replaced by water but the weight stays the same. His prominent, skinny ribs rose and fell with the ventilator, as he was no longer struggling for breath on his own. Now everyone understood why the mother was so fiercely protective. We could see the heart beating away in the wrong side of the chest and the outline of his swollen liver in the contrary side of the bulging abdomen. Everything was the wrong way round, all a source of fascination for the onlookers and presenting a daunting challenge for me. I’d seen one operation on dextrocardia in the US and another at Great Ormond Street. This would be the first I’d attempted myself.

There were still streaks of dried salt down his cheeks from the traumatic separation from his mother. What was it I used to say when asked if I was ever anxious about undertaking an operation? ‘No. It’s not me on the table!’ But although I don’t do anxiety, I was now in tiger country with an untested procedure in an unfamiliar environment and could feel sweat trickling down my back. It all felt a very long way from Oxford.

Everyone was happier when that fragile little body was covered in blue drapes, leaving just a rectangular window of dark skin exposed over the breastbone. He was now no longer a child, just a surgical challenge. That is until we heard his tormented mother banging on the operating theatre doors. She’d given her minders the slip and rushed back, and after a brief struggle they allowed her to sit in the corridor just outside. Her day had been traumatic enough without being dragged away for a second time.

Back inside the operating theatre the scalpel blade slid left to right along the length of the boy’s sternum until a trickle of bright red blood skidded over the plastic drape. The electrocautery soon put a stop to that as it sizzled down onto white bone, reminding me of that line from Apocalypse Now – ‘I love the smell of napalm in the morning.’ The whiff of white smoke told me that the diathermy had too much power and I reminded the orderly that we were operating on a child, not electing a pope, so would he please turn down the voltage.

Heart failure fluid was pushing up the diaphragm. I made a small hole in the boy’s abdominal cavity and straw-coloured fluid poured out like piss into the wound. The noisy sucker removed almost a pint into the drainage bottle and his belly flattened out. A very quick way to lose weight. The saw zipped up the sternum, spraying beads of bone marrow onto the plastic. It breached the right chest cavity, releasing a knuckle of stiff, pink, waterlogged lung. Yet more fluid spilled out, so the sucker bottle had to be changed. It left no one in any doubt that this kid was seriously unwell.

Impatient to view the congenitally distorted heart, I dissected away the redundant thymus gland and sliced open the pericardium – the fibrous sac that encases the heart – with the same excitement and anticipation as unwrapping a surprise parcel at Christmas.

Everyone wanted to get a good look at the dextrocardia heart before I started, so I took a step back and relaxed for a minute. The plan was to open up the narrowed channel below the aortic valve by coring out as much solid tumour as possible, then close the hole in the atrial septum. I gave the order to go onto the heart–lung machine and proceeded to stop the empty heart with cardioplegia fluid. It lay cold, still and flaccid in the bottom of the pericardial sac. I gently pressed the muscle and could feel the rubbery tumour through the heart wall. By now I was sure that I couldn’t reach it all with a conventional approach and that there was little point cutting into the ventricle that his circulation depended upon purely on an exploratory basis. So I told myself, ‘Just do it.’ Plan B. The eureka option, one that had probably never been done before. The perfusionist began to cool the whole body down from 37°C to 28°C. The boy was likely to be on the bypass machine for at least two hours.

At that point I had no option but to share Plan B with the rest of the team. I would chop out the boy’s heart from his chest and, with it lying on a kidney dish full of ice to keep it cool, operate on it on the bench. Then I could twist and turn the thing as much as I needed to do a good job. I considered it to be a brilliant idea, but I had to work fast.

The process was equivalent to removing a donor heart for transplant then sewing it back into the same patient. Back in my research days I’d transplanted tiny rat hearts. This boy’s heart should be no problem, even if the anatomy was unusual, so I transected the aorta just beyond the origin of the coronary arteries, then the main pulmonary artery. By pulling these vessels towards me, the roof of the left atrium was exposed at the back of his heart. I cut through the atria, leaving all the large veins from the body and lungs in place, then, lifting the ventricles out, I left most of the atria in situ. It was then, as you’d do with a donor heart, that I placed the cold, floppy muscle onto the ice.

Now I could see the tumour within the outflow part of the left ventricle. I started to dissect it out, cutting a channel through it so that it would no longer obstruct the heart. The tumour’s rubbery texture was consistent with it being benign, making me optimistic that we had done the right thing. Both my assistants were shocked and mesmerised by the empty chest and were not assisting well. And the longer this heart remained without a blood supply, the more likely that it would fail when I re-implanted it. Frankly, the Australian scrub nurse was much sharper than these trainees, so I asked her to help. She knew instinctively what was required and injected the necessary pace into the procedure.

I was torn between just doing enough or making a radical job of it. But I wanted to tell the boy’s mother that I’d succeeded in removing all of the tumour so I pursued it into the ventricular septum, close to the heart’s electrical wiring system. I knew where this was situated in a normal heart, but its location was less certain in this case. After thirty minutes I infused another dose of cardioplegia solution directly into both coronary arteries to keep the heart really cold and flaccid, and fifteen minutes later the job was done.

I took the boy’s heart back to his body, aligned the ventricles with the atrial cuffs and started to sew it in. I was really quite impressed with myself, the journal article already half-written in my head. The re-implantation process also closed the hole in the heart, so – with luck – he was cured.

This part of the operation had to be fail-safe as these stitch lines would be completely inaccessible in a beating heart. With both atria joined up again it was time to re-join the aorta and let blood back into the coronary arteries. The heart would start beating again and we could warm the boy’s body up. All that was left to do was to reconnect the main pulmonary artery. By then the surgical assistants had also warmed up a bit, on familiar territory once more with the heart back where it belonged.

Usually a child’s heart starts to beat spontaneously and quickly when its blood flow is restored, but this one was too slow. What’s more, I could see that the atria and the ventricles were contracting at different rates. This told me that the conduction system between the two was not working, which is not good as a coordinated heart rhythm is much more efficient. The anaesthetist had already noticed this on the electrocardiogram but said nothing. After cooling, the conduction system often goes to sleep for a while then recovers spontaneously.

Ten minutes later and nothing had changed. I must have cut through the electrical bundle while dissecting out the tumour. Shit and derision. He’d need a pacemaker. This made me more anxious about another issue. A transplanted heart also loses its connection with nerves from the brain, nerves that automatically speed up or slow down the heart during exercise or changes in blood volume. This denervation, together with the disruption of the electrical conduction system, could be a real problem.

My earlier euphoria, optimism and self-congratulation quickly abated, and the young mother drifted back into my thoughts. This wasn’t a good time to lose focus. There was still air within the heart chambers and it had to be let out, so I inserted a hollow needle into the aorta and pulmonary artery. Air fizzed out of both. When air entered the uppermost right coronary artery the right ventricle distended and stopped pumping.

We needed another fifteen minutes on the bypass machine for the effects to wear off. During that time I put temporary pacing electrodes on the right atrium and ventricle. We’d control his heart rate until the cardiologists could implant a permanent pacemaker. Gradually the heart function improved. Obstruction gone, lungs relieved of congestion, his life relieved of heart failure and breathlessness. Or so I hoped.

The boy’s pulse rate was only forty beats per minute, less than half of what it should have been. We increased that to ninety with the external pacemaker, and with this improvement the blood started to well up from behind the heart. I assumed that this was persistent bleeding through my stitching, so I told the perfusionist to turn the bypass machine off and empty the heart while I lifted it up to inspect the join. Nothing. It looked great. No leak.

When we restarted the machine thirty seconds later there was more blood. I inspected the joins of the aorta and pulmonary artery. No leak there, either. Eventually my first assistant spotted oozing from the aorta. The needle used to evacuate air had gone through the back, making a small hole. This would be inconsequential when blood clotting was restored, so we separated the boy from the heart–lung machine and closed the chest.

I didn’t have long to reflect on our success as a message came in from the adult cardiologists. They had just admitted a young male following a high-speed road-traffic accident. He’d not been wearing a seatbelt and his chest had impacted against the steering wheel with great force. He was in shock and his blood pressure could not be restored by fluid resuscitation.

Chest X-rays at the referring hospital had shown a fractured sternum and an enlarged heart shadow, and the veins in his neck were distended, suggesting blood under pressure in the pericardial sac. Not only that. The echocardiogram showed that the tricuspid valve, between his right atrium and ventricle, was leaking badly, hence the persistently low blood pressure and severe shock. The man needed urgent surgery, and could I please come and see him before it was too late?

I was distinctly uneasy about abandoning the boy but there was no choice. Leaving the operating theatre complex I found the mother sitting cross-legged in the corridor, alone and desolate. She’d been waiting there for five hours, and I sensed that she was about to implode mentally, her emotions bottled up for too long owing to her inability to communicate for whatever reason. And finally we’d taken away her bundle of rags. She saw me, sprang to her feet and panicked. Was the operation a success? I didn’t need to speak. Our eyes met again, pupil to pupil, retina to retina. My smile was enough, and with it the message that her son was still alive.

Bugger protocol and the audience of cardiologists. I needed to show her some affection so I held out a sticky hand, wondering whether she’d take it or remain aloof. This act of kindness unlocked the tension. She grasped it and began to shake uncontrollably.

I pulled her in and held her tight, as if to say, ‘You’re safe now, we won’t let anyone harm you any more.’ When I let go, she held on tight and started to weep uncontrollably, waves of emotion discharging onto the hospital corridor and leaving my Saudi colleagues standing in an embarrassed silence. It took a while to calm her, and they were becoming increasingly anxious about their trauma patient.

I told her that her son would shortly leave the operating theatre, that they would bring him out in an intensive care cot attached to drips and drains, and that this might frighten her. She could certainly walk with them but not interfere. Again I sensed that she understood English, but in case she didn’t one of the cardiologists repeated my words in Arabic. Then we left to review the injured man’s echocardiograms, the ultrasound examination of his heart chambers.

By now the trauma patient was dying. He had a torn tricuspid valve, a rare, high-speed deceleration injury we never see with our mandatory seatbelt law. The right ventricle was pulverised as the sternum fractured and had been driven back against the spine, the rapid increase in pressure causing the valve to burst. Now, when the heart contracted, as much blood went backwards as forwards, little was passing through the lungs and the heart couldn’t fill adequately because of blood in the pericardium. Cardiac tamponade, we call it.

Once I’d seen the pictures I didn’t waste time visiting the patient. I just needed to crack that chest, relieve the tamponade and if possible repair the tricuspid valve. We had to get him onto the heart–lung machine quickly to restore blood flow to the brain and correct his dire metabolic state. Then someone behind me whispered, ‘Don’t rush. He’s a madman. He killed the other driver.’ I said nothing. That wasn’t my business. Striding purposefully back to the operating theatre I encountered the little entourage in transit to paediatric intensive care. The fast, regular beeping of the heart rate monitor was reassuring. Without diverting her gaze the mother held out her hand as we crossed over, and I did the same. Contact.

I should have been with the boy in intensive care, at least for the first couple of hours until I was confident that he was stable. But now I couldn’t be. Soon the trauma patient was on the operating table being resuscitated. He had disfiguring facial injuries and extensive bruising over the chest wall, and the edges of the fractured sternum were overlapped with a step deformity. But it was nothing we couldn’t fix with pins and wires.

Within minutes I had the chest open and was scooping clumps of blood clot into a kidney dish. This improved his blood pressure, but his right ventricle looked like tenderised steak – and it didn’t contract any better than a steak – and his right atrium looked like it would burst. So I put the pipes directly into the major veins. As we started cardiopulmonary bypass, his struggling heart emptied out and flapped around at the bottom of the pericardial sac like a wet fish. He was safe – and just in time!

With an incision directly into the right atrium the ruptured valve was there in front of me. It was torn like a curtain, but when I stitched it like torn cloth it was easily repaired. I tested it by filling the right ventricle through a bulb syringe. No leak. So I closed the atrium and removed the snares to fill it again. The job was done. The tenderised meat functioned better than anticipated and eased itself off the bypass machine. By then I’d had enough. I left my assistants to repair the fractured sternum and close the chest. No doubt he’d survive to go to prison.

The sun was setting on a hot and difficult day. For a while I felt content, satisfied after two ‘out on the edge’ operations, difficult cases that few heart surgeons would ever encounter in their whole career. I needed a beer, many beers, but there was no chance of that. I wondered whether the mother was happier now. She’d achieved what she set out for – treatment for her dying child.

Having heard nothing from intensive care I assumed that the boy was doing fine. Wrong. They were already in trouble. For some reason the doctors had tampered with the temporary pacing box and the electric stimulus from the generator had coincided with the heart’s natural beat, fibrillating it and instantaneously inducing that uncoordinated, squirming rhythm, a herald of imminent death.

To counteract this they’d used external cardiac massage until a defibrillator was brought to his bedside. The vigorous chest compressions he’d been given had displaced the pacing wire from the atrium and, although the heart defibrillated at the first shock, the sequential pacing of atrium then ventricle no longer worked. Now only the ventricles could be paced. As a result there was a precipitous drop in cardiac output and his kidneys had stopped producing urine. The boy was deteriorating but no one had told me because I was in the middle of another big case. Shit.

Throughout this débâcle the poor mother had stayed by the cot where she’d watched them pounding on her little boy’s chest, then witnessed the electrical shock that caused his little body to spring from the bed and convulse. At least he only needed one shot at defibrillation. The resulting beep, beep, beep was of little comfort to her, however, and like her child she was spiralling down.

I found her clasping his tiny hand, tears running down her cheeks. She’d been so happy as she escorted him from the operating theatre. Now she was desolate and I was too. It was clear that these intensive care doctors didn’t understand cardiac transplant physiology.

And why should they? They’d never been involved with heart transplants so they failed to grasp that taking the heart out of the body cut off its normal nerve supply. They were pacing the heart at 100 beats per minute with an insufficient volume of blood while simultaneously flogging it with high doses of adrenaline to raise the blood pressure. This constricted the arteries to his muscles and organs, substituting blood pressure for flow and once again producing metabolic mayhem.

The nurse looking after the boy on the intensive care ward seemed anxious and was pleased to see me. A very capable New Zealander, she clearly did not rate the critical care registrar. Her opening remark was, ‘He’s not passing urine and they’re not doing anything about it,’ followed more directly with, ‘If you’re not careful they’re going to fuck up your good work!’