Читать книгу Recalculating: Steve Chapman on a New Century - Steve Chapman - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIntroduction

As the end of the 20th century approached, Americans were gripped by anxiety about a looming, inescapable danger. Terrorism? War? No, a computer problem that threatened severe and widespread disruption of electronic networks around the world. Y2K, as it was known, raised the prospect that at the dawn of the new millennium, we would all be huddling anxiously in the dark. People bought gallons of bottled water, stockpiled matches, candles and batteries, made sure their cars had full tanks of gas, and loaded pantries with imperishable foods.

It all turned out to be a phantom threat. As midnight struck in one country after another in time zones east of us, Americans breathed sighs of relief, chilled the champagne, and got ready to toast the New Year. We had averted catastrophe. It was a promising omen for the 21st century. It was also a deceptive one.

The 1990s were, by most standards, good years. Looking back on the bitter political wars between President Bill Clinton and Republicans in Congress, which led to his impeachment, it’s hard to figure out what charged the furies. The economy was in the midst of the longest peacetime expansion since World War II, with low inflation, a booming stock market and an unemployment rate once considered unattainably low. Things went humming along for so long that in 1998, The Economist dared to ask, “Has the business cycle finally been conquered?”

The crime rate, which had hit a blood-curdling peak early in the decade, was headed downward. Welfare reform was a success that, combined with a vigorous economy, would transform the culture of poverty and lift the underclass into self-reliance.

The Cold War was over, and Russia, along with its former satellites in Eastern Europe, was breathing free air. We were the only superpower on earth. The spread of democracy around the world heralded a new age. After the first war with Iraq, which ended in a clean triumph, U.S. military ventures were few and modest — Somalia, Bosnia, Kosovo, Haiti. The battle of Mogadishu, the subject of the book and movie “Black Hawk Down,” was our idea of a colossal military debacle.

The threat of a nuclear exchange between hostile superpowers had vanished. Terrorism was a low-level irritant that rarely intruded into mass consciousness. When George W. Bush was inaugurated president in 2001, The Onion headline read, “Our long national nightmare of peace and prosperity is over.” Seriously, we might have asked, what could go wrong?

A lot, it turned out. On January 1, 2000, we didn’t imagine the surprises that lay in store. The first was the 2000 presidential election, in which George W. Bush, who came in second in the popular vote, won anyway — with an unprecedented assist from the Supreme Court. His inaugural motorcade was met by demonstrations, chants of “Hail to the Thief” and airborne eggs. Less than nine months later, operatives of a radical Islamic group called al-Qaida hijacked airliners and crashed them into the twin towers of the World Trade Center and the Pentagon, the worst terrorist attack in American history.

Soon our troops were fighting in Afghanistan, which had provided refuge to Osama bin Laden as he plotted against us, and before long, the Bush administration had set out on the path to invading Iraq. Neither war went as expected, and both lasted far longer and cost far more American lives than anyone expected.

So much for peace. Prosperity? It stumbled in the mild recession of 2001, only to collapse in the Great Recession of 2007, the worst since the days of Herbert Hoover. As of this writing, the economy has yet to regain its previous vigor, and the proportion of working-age Americans with jobs fell to the lowest level since the 1970s. We still have troops in Afghanistan, and U.S. forces are carrying out attacks in Iraq (and Syria) against an enemy that our occupation of Iraq helped spawn.

It has not been a good century for the country or the advocates of assertive government. The Iraq war proved the fallibility of our leaders in diagnosing dangers, formulating strategy and handling unforeseen events. The recession persisted despite the Obama administration’s $800 billion stimulus package and the Federal Reserve’s prolonged commitment to easy money and low interest rates. Obamacare was botched in execution and, so far, remains a work in progress. Anyone who began the 21st century believing that the government does few things well would not be dissuaded by the record of the past 16 years.

But there is some good news. In some respects, individual freedom has made big gains. Gay marriage is the law of the land. Four states have legalized recreational marijuana. Gambling, once confined to a few outposts, has spread to 48 states. The Internet has put free expression beyond the power of censors, at least this side of China. The death penalty is used only rarely, and 19 states have abolished it. Economic regulation is far less extensive and heavy-handed than it was a few decades ago.

Barack Obama, after preserving George W. Bush’s program for surveillance of phone records, agreed to take those records out of the government’s hands and limit their use. The Iraq war has soured the public on ambitious wars of choice. The nuclear deal with Iran has averted another potential war, at least for the time being. There is considerable resistance to new free trade agreements, but little appetite to roll back old ones. International commerce faces fewer barriers than it ever has.

My views are broadly libertarian. I believe democracy, capitalism and the Bill of Rights are among the most beneficial things ever created. I note that government programs often fail at their objectives and sometimes backfire. I think that people should be allowed to make their own choices as long as those choices don’t inflict unwarranted harms on other people. I have little confidence in the ability of our government to transform foreign nations by force.

But I have an allergy to dogmatic ideology. Any ideology – this seems so obvious it shouldn’t need to be stated, but it does – has to be constantly tested against the evidence of how the real world functions. And when the two conflict, as they sometimes do, I prefer reality over presuppositions. Judging from some politicians and commentators, that is not a universal preference.

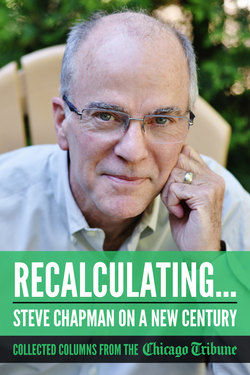

I have been writing a column for The Chicago Tribune since 1981, but here you will find only columns written since 2000, because that period strikes me as more than sufficient for a single volume. I’ve chosen the entries partly to cover the most important issues and events, partly to address matters that have been overlooked, and partly to entertain.

As an opinion writer, I am habitually prone to optimism even during the worst of times. Without it, there would be little point in trying to contribute to debates and change minds. Of course, I could be delusional. If so, please let me go on that way.

The Russian revolutionary Leon Trotsky once wrote, “Anyone desiring a quiet life has done badly to be born in the twentieth century.” The same could be said of our era, but this century has a long way to go to equal the horrors of the past one. And has 85 years to do better. Besides, as Ohio Gov. John Kasich exclaimed on the campaign trail last year, “But my goodness! We live in America. I mean, we have a lot going for us.”

Acknowledgments

There are four people without whom I literally would not have had a career in journalism: Nancy Sinsabaugh, Scott Kaufer, Nicholas Lemann and Michael Kinsley. They’re just the first in a long line of those I have to thank. The late executive editor Maxwell McCrohon hired me at the Tribune, and his successor, James Squires, entrusted me with a twice-weekly column. I’ve worked for five different editorial page editors at the Tribune: the late Jack McCutcheon, Jack Fuller, Lois Wille, Don Wycliff, Bruce Dold and John McCormick. No journalist could ask for better ones. Likewise with the Tribune’s editors, who include Howard Tyner, Ann Marie Lipinski and Gerould Kern.

I have had many valued colleagues on the board, the current ones being Marie Dillon, Elizabeth Greiwe, Marcia Lythcott (who edits my column), Michael Lev, John McCormick, Kristen McQueary, Clarence Page, Scott Stantis, Lara Weber, Paul Weingarten and Eric Zorn. They provide endless stimulation, provocation and friendship. Among the former editorial board colleagues I especially miss include Dianne Donovan, Terry Brown, Pat Widder, Storer Rowley, Alfredo Lanier, Naheed Attari, Ken Knox, Cornelia Grumman, Dodie Hofstetter, Laura Moran Claxton, Kristin Samuelson, Megan Craig, Megan Crepeau and Jessica Reynolds.

My column is syndicated by Creators Syndicate, to which I was recruited by Rick Newcombe shortly after he founded it in 1987, and I’ve had the pleasure of working with a string of excellent editors. Among those who worked on the columns in this volume are Karen Duryea, Jessica Burtch and David Yontz.

My education on a variety of topics over the years has had abundant help from many people. Among those who have contributed more than their fair share are John Mearsheimer, David Boaz, Barry Posen, David Henderson, Ronald J. Allen, Geoffrey Stone, Richard Epstein, Karlyn Bowman, Thomas Hazlett, Daniel Polsby, Ethan Nadelmann, Albert Alschuler, Allen Sanderson, Stephen Schulhofer, Franklin Zimring, and Gary Kleck. Richard Norton Smith has been a close friend and an inexhaustible well of information on politics and history since our college days.

My perfect children, Ross, Keith and Isabelle, have furnished me with many insights, opinions and column topics, as well as unending love and support. I’m lucky to have been embraced and informed by my matchless stepsons and daughters-in-law: Chris and Cassie Mycoskie, and Craig and Amy Mycoskie. The first reader for my columns is a born copy editor and the love of my life, Cyn Sansing Mycoskie, whom I had the good fortune to marry in 2007. For her and all of the above, my gratitude is immense but inadequate.