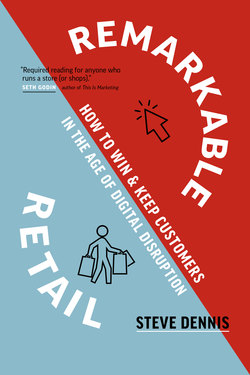

Читать книгу Remarkable Retail - Steve Dennis - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 5

The Amazon Effect

“Your margin is my opportunity.”

—JEFF BEZOS

Because of Amazon’s size, growth, and disruptive impact, folks tend to get a few facts wrong about the company. First, Amazon is not the world’s biggest retailer—at least not yet. That position is still held by Walmart. Second, while Amazon’s online sales dwarf other competitors, it still has only about a 4 percent share of total US retail, with more than half of that derived from independent merchants selling through their platform, not their own direct sales to consumers. Amazon’s market share internationally is much smaller in most markets. In many cases it is growing rather quickly, yet it has formidable rivals such as China’s Alibaba and JD.com, India’s Flipkart, and Argentina’s Mercado Libre.

The main thing most people get wrong about Amazon is the belief that it makes a lot of money. Certain parts of Amazon have started to do well—most notably Amazon Web Services, which provides a cloud-based computing platform for a slew of industries, as well as its rapidly growing, cash-generating advertising business. However, the retail division has barely broken even for most of its history and didn’t start to regularly earn a profit in retail until just a few years ago. Even now their margins are often below industry averages, though sales growth remains robust.

Figure 5.1 Amazon’s Revenue versus Profit

Source: Vox; data from Amazon13

Moreover, when its continuing rise of fulfillment and shipping costs—which have been trending toward nearly 27 percent of sales—is taken into account, it’s hard to see how retail will become strongly profitable anytime soon.

Figure 5.2 The Growing Weight of Amazon’s Logistics Costs

Source: Statista14

There is no sense that Amazon—or Wall Street—is terribly concerned. Amazon has created an incomparable flywheel by offering unparalleled selection, fast and cheap delivery, and generally sharp product pricing. This has been great for consumers and investors, but particularly brutal (or impossible) for many competitors to profitably combat.

So Amazon finds itself in an enviable position on many fronts—and the main one is that investors continue to value growth over profitability. This allows Amazon to experiment with new concepts aggressively and invest in building long-term infrastructure, especially in product delivery.

Stop Blaming Amazon for All of Retail’s Woes

As stores close by the thousands, once-prosperous chains go bankrupt, and scores of malls are bulldozed or massively repurposed, it’s become common to lay the blame on the rise of e-commerce generally and on Amazon in particular. Given the rapid growth of online shopping and the fact that Amazon now controls some 40 percent of the e-commerce market, it’s easy to jump to that conclusion. Yet this argument has two huge problems.

First, as we have seen, some of the most disrupted sectors were in decline well before Amazon was a blip on the radar screen. The moderate department-store segment is a case in point. Amazon and other online-only players have only begun to have a material impact on these companies in the last few years.

Second, absolutely nothing prevented any of these retailers that have lost share to online retailers from developing their own similar e-commerce capabilities. In fact, a brand with really great digital capabilities combined with kick-ass brick-and-mortar assets that are well integrated should have important advantages in competing with online-only players. That is one of the main arguments of this book.

By way of illustration, I worked in senior roles for two retailers that began making significant e-commerce investments in the late ’90s and, as a result, captured more than their fair share of the growth in online shopping. The first, Sears, lost its way for other reasons, but for many years the company’s appliance and home improvement businesses were clear leaders in what we now call “omnichannel.” The Neiman Marcus Group, while it was relatively slow to integrate its cross-channel offerings and focus enough on acquiring younger customers, did make growing online shopping a priority more than two decades ago. For the most part the leading luxury department store in North America, despite selling in a very mature category with escalating competition, has held its share of the market, while at the same time delivering solid operating profitability. Online sales now represent nearly a third of its total revenues, and its best and most loyal customers regularly shop across all channels.

Many major national brands have yielded little or no share to Amazon and other pure-play competition. That’s not to mention the many local, regional, and specialty stores that have a laser-like focus on a particular customer segment, deliver superior customer service, and provide a unique product and/or service mix.

The real question for retailers is, do you let the shifts destroy you or do you turn them to your advantage?

Okay, Maybe Blame Them a Little

Still, there is no question that Amazon has wreaked havoc with many segments. It built its first phase of growth by targeting products that were easily understood online and that could be delivered digitally or relatively inexpensively by mail (books, music, games). The first wave, which was mostly complete more than ten years ago, decimated most of their direct brick-and-mortar competitors.

As Amazon expands into many more categories, including services, it grows ever closer to becoming the so-called everything store. While a few sizable categories, such as luxury fashion, are not well represented on Amazon, the company’s virtually endless aisles—through both its direct selling and its marketplace—give it relative assortment dominance over just about any retailer on the planet. Perhaps for this reason many people think Amazon’s market share is greater than it actually is. But the fact that, according to one study, nearly two-thirds of all online product searches originate at Amazon15 underscores the broadly held consumer belief that Amazon will likely have the product they want, or at least will serve as a useful source for product and pricing information to aid in their shopping journey that may result in a transaction elsewhere.

In many instances Amazon is also a price leader. While it doesn’t always offer the lowest price, it has a strong reputation for good value, and its sophisticated algorithms, as well as its ability to frequently absorb below-average industry gross margins, give it a major competitive edge. Also, as a well-established brand, it has trust advantages over the smaller, unknown, or even potentially fraudulent merchants that may show up in searches for the lowest price.

Arguably, where Amazon has been the most disruptive is redefining the notion of convenience. Much of this stems from ever-shorter product delivery times. For many years a centerpiece of Amazon’s offering has been its Prime program, which has free two-day delivery as a core benefit. With more than 100 million Prime members in the United States alone, many shoppers have come to expect free and fast delivery as the de facto standard. And Amazon keeps raising the stakes, pushing to provide next-day delivery in many major markets, offering two-hour grocery delivery, and experimenting with other convenience-oriented options like placing Amazon pick-up lockers in Whole Foods and Kohl’s stores.

The other aspect of Amazon’s fundamental redefinition of convenience is the shopping experience on the site itself. Supplementing its impressive assortment are powerful features like one-click ordering, subscription replenishment options, and a plethora of preference settings that make purchasing faster and easier.

Any retailers that go head-to-head with Amazon will likely find it very difficult to compete on these dimensions. And even where they can, it is virtually impossible to do so profitably. That creates a major dilemma for many of them. Failure to be at parity with Amazon means ceding market share. Trying to achieve parity means tanking earnings.

Understanding Buying vs. Shopping

As dominant as Amazon has become in many areas, it’s important to understand that it has, as noted retail strategist Liam Neeson might put it, “a very particular set of skills.” This is best shown by examining the difference between “buying” and “shopping.”

In this way of dissecting the retail world, “buying” is more task-driven or mission-focused. It’s mostly functional. The consumer already has a clear idea of what he or she wants and generally wants it quickly and at a decent price. Buying is more commodity-oriented and search typically plays a key role. Amazon—and e-commerce more broadly—does especially well here.

“Shopping,” on the other hand, is more nuanced and complex, typically involving more exploration and browsing. Generally speaking, browsing on Amazon can be a frustrating experience. When shopping, rather than looking for a specific item, the consumer may be seeking a more complete solution or inspiration and often requires some form of advice. Shopping also tends to be more emotional, with a greater emphasis on the full experience rather than merely checking an item off a to-do list. The role of physical stores is dramatically more important in shopping than buying, and as a consequence Amazon and other sites that are dominantly or entirely e-commerce have a disproportionately lower share.

So when we talk about Amazon’s retail dominance (and in general much of the hyper-growth in online retail), we need to remember that the vast majority of it is occurring in buying, not shopping.

The De-Schlepping of Retail

Within “buying” lies an important sub-sector where Amazon is very strong. At a 2018 industry conference, former J.Crew CEO Mickey Drexler asked the crowd, “Why schlep paper towels . . . why schlep dog food . . . why schlep a lot of things?”16 When we know exactly what we want sight unseen—and especially when that item is big, bulky, or frequently purchased—having somebody else deliver it is so much easier. This is particularly true if one is already a Prime member and the price of getting it shipped is zero.

While Amazon is a big beneficiary of this phenomenon, newer brands, from Chewy.com (pet supplies) to Boxed to subscription razor services like Harry’s, Dollar Shave Club, and Billie are leaning into this opportunity. They either emphasize bulk delivery of products and bundles or seek to enroll customers in scheduled replenishment of frequently used products. They zoom in on a particular set of points in the buying process and eliminate the friction. Afraid of running out of essential items? No problem! Just subscribe to our service and that fear is gone. No room to lug large and unwieldy items in your car or on the bus? No worries! We’ll deliver it to your home or apartment.

Let’s Get Physical

Some experts believe that Amazon’s ability to sustain hyper-growth over the long term will be increasingly driven by a more aggressive investment in physical retail. What is becoming clear is that e-commerce growth, while still very robust, is beginning to slow, and Amazon’s stock price is strongly influenced by its growth story. Some leveling-off in Amazon’s online growth is inevitable, stemming from the fact that the product categories that are maturing most rapidly are among Amazon’s most highly penetrated segments, such as books, consumer electronics, and more commodity-like household items.

As alluded to earlier, Amazon already has a substantial physical retail presence by virtue of its 2017 Whole Foods acquisition. But it continues to experiment aggressively with various brick-and-mortar concepts, including Amazon Books, Amazon Go, and Amazon 4-star stores. Amazon is rumored to be considering opening thousands of Amazon Go locations in the new few years, in addition to reported plans to become bigger in physical grocery store retailing by launching its own mass-market concept.

Amazon has also been experimenting with and expanding various “click and collect” operations. At the end of 2019 it had more than 2,800 Amazon Lockers across 900 US cities. Many Whole Foods stores now have prominent Amazon pick-up and return areas. And most significant (so far) is its partnership with Kohl’s, where all roughly 1,150 stores now accept Amazon returns, even if the customer no longer has the shipping box.

These initiatives are addressing important friction points in buying from an online retailer. They also serve to partially counteract an edge major competitors like Walmart and Target have with those consumers who lack a good way to receive packages at their home or workplace, or who find returning a product through the mail a major hassle or a costly alternative.

While such services will help serve some needs, they are unlikely to help Amazon compete when it comes to growing significant sources of incremental revenue currently held by predominantly brick-and-mortar retailers. Physical store market share remains quite high in many substantial retail sectors like home improvement, furniture, and groceries, largely owing to how critical the in-store experience is for most of these purchases. Undoubtedly both evolving consumer preferences and technological advances will continue to help digital chip away at even the greatest strongholds of brick-and-mortar shopping. But many of these gains will come slowly, and Amazon, particularly given its sheer size, will need to unlock major new sources of growth to sustain its present trajectory. It’s hard to imagine how it will do that over the long term without a much greater physical retail presence.

The Amazon Stranglehold?

Although Amazon clearly has some challenges in achieving greater profitability while sustaining hyper-growth, the naysayers must keep certain aspects of the future impact of the Amazon effect in mind:

• First stop Amazon: The fact that a large percentage of consumers engaged in online product discovery reflexively make their first stop Amazon gives it a huge strategic advantage.

• Massive customer insight: While Amazon is fundamentally a logistics or supply-chain company, it is a customer data company and a consumer insight machine as well. It’s hard to fathom the vast richness of the behavioral and transactional data the company possesses. Much of it is employed to power pervasive product recommendations and dynamic site personalization. Amazon’s future potential to glean and leverage greater insight is staggering when one considers its overall household penetration and the breadth of products and services it sells. This data can also be the foundation for launching new offerings in health care, consumer credit, insurance, and other related services.

• Private brand development: Private brands have been part of the retail playbook for years. A retailer’s exclusive offerings create a point of differentiation and help neutralize direct price-comparison shopping. At the same time, they offer consumers a strong value option and generally give the retailer better product margins. What sets Amazon apart here is twofold. First, no other retailer (except maybe Alibaba) has the quantity and quality of data to best determine the market positioning of new private-label products. Second, armed with that data, Amazon can strategically market its own products to exploit vulnerabilities among competing manufacturer brands they already carry. Amazon already has well over 100 of its own brands and exclusive product lines and continues to roll out more. Some are commodity oriented, like AmazonBasics and Amazon Essentials. Others have no obvious tie to Amazon, such as its many fashion brands, like Lily & Parker, Lark & Ro, and Tresori.

• Mostly free delivery: Once a consumer signs up for Amazon Prime and pays the annual fee, delivery is free, regardless of the amount of stuff one buys or the price of the item. This gives Amazon an important advantage over retailers that charge fees, have minimum orders for free delivery, or do not have the ability to absorb the added expense. It also helps prevent a shopping trip that might have otherwise driven traffic to a competitor.

• Last-mile delivery infrastructure: Amazon has built out incredible logistics capabilities. At first, its supply chain centered on the picking, packing, and shipping of items delivered via the existing postal service and package delivery companies—not unlike the mail-order catalog companies that have been around for ages. Over time it has gotten deeper and deeper into owning or directly managing other logistical aspects central to effective and efficient home delivery. The company already operates more than fifty of its own planes and a vast fleet of local delivery vans and has many thousands of independently contracted delivery drivers using their own vehicles. This ever-expanding infrastructure allows Amazon to expand the array of products it can sell, improve order fulfillment times, and build a competitive moat around its delivery operations.

Any combination of these means that Amazon may put the squeeze on a given competitor or massively shake up a category it decides to double down on. Even the rumor that Amazon might be considering entering a category or focusing on one more intensely can send ripples through an industry, as we have seen multiple times, particularly in the supermarket arena.

No Sympathy for the Devil

For many retailers, Amazon has become the target when they want to decry the many factors they see as the company’s unfair advantages. Amazon’s ability to invest behind growth at the expense of margin is the envy of most. Few love the fact that despite being the second-biggest retailer on the planet, the company pays little or no US federal income tax. Working conditions at Amazon fulfillment centers have come under increasing scrutiny. Many see the extensive packaging involved with e-commerce as unfriendly to the environment, and as the leading culprit, Amazon gets a fair share of the heat.

Moreover, many manufacturers selling directly through Amazon, along with those businesses leveraging the Amazon Marketplace, have a love-hate relationship with the company. Some have greatly expanded their reach by selling through Amazon. Others realize that they will be walking away from significant business if they fail to distribute through the company. But ultimately they know that Amazon holds most of the cards and regularly flexes its muscles to remind them. While there are advantages to dancing with to the devil you know, at the end of the day they are still the devil.

Chasing the Great White Whale

Amazon is an undeniable force. A behemoth. A colossus. The flywheel effect it has put in place, and its ability to fund growth without a heck of a lot of concern for profits, is a huge advantage, which virtually guarantees it will continue to gobble up market share for the foreseeable future.

Amazon is powerful, but it is not invincible. Yet it is not very likely that anyone reading this book will contribute to the company’s downfall. Nor are there many parts of Amazon’s core business where its vulnerabilities can be profitably exploited. But there are many aspects of retail where Amazon is not—and will not be—especially successful.

Amazon has incredible momentum, but it is not going to take over the vast majority of retail—at least not in anyone’s sensible planning horizon. In plenty of areas Amazon has a long way to go before it will ever gain meaningful market share.

Our job, therefore, is threefold. The first is to stop chasing Amazon like Ahab obsessively pursuing Moby Dick. You won’t catch it and even if you do, before long you will likely get crushed or eaten alive. The second is to separate the myths from the reality. The third is to focus your strategy on the areas where Amazon is not, and will not be, an unbeatable competitor anytime soon.

This is not to say that Amazon should not be a potential distribution partner. This doesn’t mean that many things that Amazon does well should not be studied and potentially made part of your organization’s capabilities. But it does mean accepting the fact that we are not going to beat Amazon at its own game.