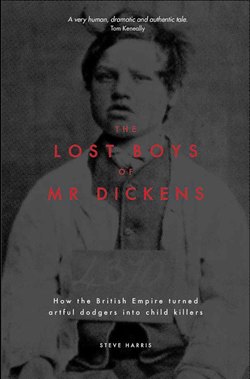

Читать книгу The Lost Boys of Mr Dickens - Steve Harris - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление3

A THIEF BY REPUTE

‘Stop thief! Stop thief!’ There is a passion FOR HUNTING SOMETHING deeply implanted in the human breast. One wretched breathless child, panting with exhaustion; terror in his looks; agony in his eyes.

— Charles Dickens, Oliver Twist

The names Henry Sparkes and Charles Campbell meant nothing, just two of thousands of otherwise anonymous and forgettable boys caught up in Britain’s passion for hunting, convicting, and transporting its unwanted ‘alien vermin’ to Van Diemen’s Land. But these two would, uniquely, become household names: the only two boys wanted for murder.

Those who loved Dickens’ reportage and characterisation of the injustices facing Oliver Twist boys could sense that when the full story of Sparkes and Campbell’s lives and their time at Point Puer was revealed, it would be a tale worthy of attention of the great author.

Henry Sparkes was born around 1826 in Nottingham, 120 miles (200 km) north of London. Emerging as a world capital of lace-making, with nearly 200 different manufacturers and 70 hosiery makers, Nottingham had been lauded at the turn of the century for its prettiness but had rapidly become an industrialised and over-crowded home for 50,000. The ‘deplorable…defy description’ squalid yards and alleys of its lower classes led renowned water and civil engineer Thomas Hawkesley to judge it the worst town in England.1

In the squalor many families fell victim to Britain’s first outbreak of Asiatic Cholera after sailors brought it from Bengal in 1831 to the port of Sunderland, from where it spread across the country and claimed 52,000 lives.2 In Nottingham the scourge infected those ‘Streets and Courts filthy, ill ventilated and crowded with inhabitants too poor, dirty or dissipated to procure necessary food or use the most common means to secure health’,3 and in just a few months more than 300 people died.4

Disease and deprivation were a double jeopardy for many families and their children. Small boys like Henry Sparkes were too young to fully understand their circumstances and the consequences of thieving to survive. But Sparkes came to learn the realities of how one’s life could quickly change on 31 December 1838. A day that saw the twelve-year-old in a cell, waiting for a bailiff to march him into the Nottingham County Sessions to face Lancelot Rolleston, Esquire and Conservative MP.

At 10am, the clerk of the court commenced the day’s sitting by reading a proclamation in the name of the teenage Queen Victoria, crowned at Westminster Abbey just six months earlier. The proclamation discountenanced ‘all vice, immorality and impiety’, and judges around the country took this as a Royal ‘command’ to ensure everyone would ‘fulfil the duties of religion and support the authority of law’ and allow the country to ‘resist the machinations and the violence of those who have declared war on this country’.5

On this Monday morning, Judge Rolleston told the Grand Jury he was pleased with ‘the lightness of the calendar’6 but the court would still not rise until 7pm, and Her Majesty’s command meant that fifteen boys were not going to get much leniency for stealing clothing and food, even for first-time offences: a fourteen and a sixteen-year-old who stole four fowls were sentenced to a whipping and six months in prison; two boys, aged twelve and fourteen, were sentenced to a week in solitary and a whipping for stealing pork pies; the others, those with prior offences, received transportation for seven or fourteen years.

Henry Sparkes was the last boy to appear, another of the under-sized boys found in inferior districts of towns and cities, with a background heard every day in courts around the country. Just a year or two earlier he had been sentenced to three months in Southwell House of Correction for being found on premises in the night-time, presumably on a thieving foray. Magistrates hoped Houses of Correction — commonly known as Bridewells after the prison and hospital established in the 1500s to punish the disorderly poor and house homeless children in London — would deter young boys from a life of crime by instilling ‘habits of working and moral guidance to reform their character’. Magistrates typically declared to boys they had been found guilty of a crime which not long before would have meant forfeiture of their life but hoped that after an initial departure from the path of honesty an escape from hopeless servitude would make them a more worthy member of society. They then gave what was called a nominal punishment of three or four months imprisonment.

But working the treadwheels, known as ‘everlasting staircases’, and Southwell’s moral guidance had not kept Henry Sparkes on a path of honesty. His own father twice charged him with ‘robbing him of fifteen shillings, and…again charged by him with stealing other moneys’7 — although, this was not uncommon and not always the truth. A few fathers and stepfathers might have been genuinely motivated to keep their boy on the ‘right’ path, but many contrived charges to get rid of children, tiring of a boy thief not delivering enough, or wanting the Houses of Correction to bear the cost of housing, food and clothing. In a report to Lord John Russell, leader of the Whigs, magistrate William Miles explained that:

[some parents] turn their children out every morning to provide for themselves, not caring by what means they procure a subsistence so that the expense of feeding them does not abstract from their means of procuring gin or beer…other parents require their children to bring home specified sum every night to obtain which they must beg or thieve…others hire out their children to beggars for threepence a day (a cripple is worth sixpence).8

The court heard Henry Sparkes had once been charged with stealing a pony but ‘on account of his extreme youth he was not prosecuted’9 but ‘extreme’ youth was no longer his refuge. He was now charged with the theft of a total of three pence from two women on 21 October:

Henry Sparkes, late of the parish of Redford in this county, labourer, for feloniously stealing, taking and carrying away one piece of the current copper coin of this realm called a penny and one other piece of the current copper coin of this realm called a halfpenny of the monies of Mary Fletcher, and one other piece of the current copper coin of this realm called a penny and one other piece of the current copper coin of this realm called a halfpenny of the monies of Ann Chambers.10

For young thieves, life on the street was one of chance, of always ‘calculating all things to a nicety…chances of detection, chances of prosecution and chances of acquittal…’.11 Having been detected and prosecuted, Sparkes was now taking his chances that he might win some leniency by pleading guilty, but such hope dissipated when the arresting constable who had detained him overnight revealed that ‘on bringing him to jail he was found to have taken two pairs of stockings from the constable’s house’.12

Such a perceived wantonness to ignore magisterial admonitions, and an inability to resist thieving even from an arresting constable, was not going to receive a sympathetic ear from Her Majesty’s judges dealing with those who ‘declared war on this country’. Courts were tired of such repeat offenders. Magistrates often declared: ‘Prisoner, what can we do with you? We have done everything to reclaim you. We have imprisoned you over and over again, and given you frequent floggings, yet all is of no use.’13 An offence might appear petty, but, as one Middlesex magistrate explained, if they were ‘well known to be dangerous characters…you sometimes on account of badness of character sentence them to transportation’.14

Tearful pleas and tales of poverty, hunger, abuse and abandonment occasionally pained a judge or magistrate, but often their hearts were, as Dickens termed it, ‘water-proof’.15A common exchange was that of a ten-year-old boy appearing at Mansion House, London, on a charge of pickpocketing a handkerchief. Asked about his parents, the boy replied ‘father lives nowhere’s, ‘cause he’s dead’, didn’t know where his mother was, and ‘I an’t got nobody to go to’.16

Police said it was evident the youngster ‘had no friend in the world’ and that bigger boys took advantage of him, leading the alderman hearing the case to declare that: ‘from motives of humanity he should be obliged to send the unfortunate boy for trial, in the hope that he would be transported.’ When the pickpocket victim asked if he could now withdraw his prosecution against such ‘a mere infant’, the alderman said: ‘You surely wouldn’t want to find him starving, and the only way we now have of preventing him is by committing him for trial.’17

Henry Sparkes did not have much time to weigh whether he faced transportation as ‘a dangerous character’ or ‘from motives of humanity’. Samuel Fletcher and his daughter Mary quickly outlined the theft of three pence and the jury found he did ‘feloniously steal, take and carry away [the money], against the Peace of our said Lady the Queen, her Crown and Dignity’,18 and at the end of what had been a long day, the last in another long criminal year, Judge Rolleston swiftly reached his decision: ‘From such a catalogue of crimes, the Court remarked that it was impossible by any imprisonment that he could be reformed.’19 ‘He would therefore be placed in the penitentiary, Millbank’20 before being ‘transported for the term of seven years to such place beyond the seas as Her Majesty by and with the advice of her Council shall direct’.21

Four hundred miles (640 km) away, Charles Campbell had been walking the same familiar life path in the north-eastern port town of Aberdeen, where the Dee and Don rivers meet the North Sea. It had grown rapidly on the back of ships, fish and textiles to become one of the biggest provincial towns in Britain. But, like Sparkes’ Nottingham, it was struggling in the 1830s with juvenile vagrancy and crime. Barely one in twenty-five children were in school, with hundreds begging and thieving. Some sixty percent of children, according to the inspector of prisons, were orphans or children of convicts, or parents who on entering a second marriage had ‘thrown them upon the world without means of support’.22

When he was just nine or ten-years-old, Charles Campbell and another boy were found in October 1837 to have stolen clothing, a gold ring and pawn tickets from a woman’s house in the Green of Aberdeen. They pleaded guilty and were each sentenced to ten days. At the beginning of 1840, as ‘George Hendry Henderson or Campbell’ he was found guilty of stealing a cotton shirt and night cap from a house and sentenced to thirty days with hard labour at Aberdeen House of Correction. But he resumed thieving immediately after his release, pleading guilty under the name of ‘George Campbell’ to stealing clothing from a house in Upperkirkgate. This time he received sixty days with hard labour.23

On 23 September 1840, the name Charles Campbell appeared again on the Aberdeen Circuit Court of Justiciary list. After a ‘very earnest and impressive prayer’, Judges Lord Medwyn and Lord McKenzie and a jury panel began working their way through the thefts, forgery, and house-breaking. One ‘little boy’, William Mitchell, pleaded not guilty but having the ‘habit and repute [of] a thief’, was sentenced to eighteen months imprisonment; another boy, William Burnett, only had to wait five minutes for the jury, after ‘evidence…tedious and uninteresting’, to find him guilty of house-breaking and theft of £17, for which he was sentenced to seven years transportation. Nineteen boys appeared that morning, their guilt and punishment all decided in just two hours, with eight sentenced to be transported for seven or fourteen years.24

Even among under-sized boys, Charles Campbell stood out. He was just 4 feet (122 cm) tall with a shock of red hair barely visible behind the dock railing. He was charged with Alexander Boynes of breaking and entering another house, this time in Shiprow, the street running from the harbour to the heart of the town, and stealing three cotton shifts.

Campbell was warned pre-trial that if he confessed, or was found guilty, he ‘ought to be punished with the pains of the law to deter others from committing the like crimes’.25As Campbell and Boynes could not write, a sheriff prepared a statement on which they put their mark, ‘accepting’ the charges and pleading guilty that each, ‘or one or the other of you’, had ‘wickedly and feloniously’ broken into a widow’s room and stolen a cotton shift from her, and two other shifts owned by another woman.26

Campbell told the court he believed he was eleven or twelve years old. He was a native of Aberdeen but had been ‘absent’ for three months, perhaps a sly reference to his time in the House of Correction, and had only been in the city one night, with no place of residence, when arrested. The truth of his birthplace is unclear, but he was later listed in Tasmanian convict records as having been born in Dublin, and been a ‘cotton spinner’, with a broken finger.27 Thousands of Irish families and individuals did move to England and Scotland to escape the 1831–32 cholera pandemic or in pursuit of work in cotton mills and textile factories, where boys’ small fingers were applied to dangerous machine tasks, 5am to as late as midnight, for perhaps a sixpence or a shilling. Whatever their background, unsurprisingly many boys saw street thieving as safer, more rewarding and exciting.

Witnesses told the court they had seen Campbell and Boynes lingering in the Shiprow building. A Mrs Mitchell said Boynes ‘came to my door asking for charity, but got nothing, I desired him to go to work’.28 She then saw him outside the room of widow Margaret Grant, who had locked her garrett room before returning to find a chair at her door and some boards removed from above the door.

Perhaps in a protective ruse, or mere brazenness, Campbell was also seen going to another room again ‘asking for charity’, with ‘his coat buttoned and something bulky below it…some white cloth sticking out below his coat’.29

Out in the street, Campbell’s number was up when a sailor overheard him tell Boynes ‘I winna tell if you dinna tell’, to which Boynes responded ‘and I winna tell if you dinna tell’. The sailor could see something stuffed underneath their jackets and enjoined a fellow sailor at Trinity Quay to follow the boys and apprehend them. Spotting the sailors, Campbell ‘made off at a quick pace’, while Alexander declared ‘it was not me who did it but that boy’ before running off himself. When Campbell was seized he reciprocated, saying, ‘it was not me who stole them, it was that boy running away,’ pointing to Boyne.30

Questioned at Aberdeen police station each boy continued to blame the other. Notwithstanding their ‘dinna tell’ compact, a sergeant said Boyne told him they ‘had been on the outlook all that day in Shiprow to steal something at Campbell’s suggestion to enable him to procure pies in the evening’.31 He maintained Campbell went into the widow’s room and emerged with the cotton shifts, giving him one to wear or sell in which case ‘he would get a sixpence for it’.32

The ‘it wasn’t me it was him’ ploy was oft-used among street-wise juvenile pickpockets and thieves hoping it would help their chances if they could create doubt or convincingly point to the real ‘baddin’. But the police were not persuaded by Campbell’s efforts to pin the crime on Boynes, or his cunning argument that he had not broken into the garret room because its door was not locked, and knew Campbell ‘to be by habit and repute a thief’, convicted three times under the names of Charles Campbell, George Hendry Henderson/Campbell, and George Campbell.33

When the jury foreman duly announced the charge unanimously found proven, Campbell’s final ‘chance’ rested with Lord Medwyn, a Scottish Episcopalian who had edited a new edition of the catechism: ‘Thoughts concerning Man’s Condition and Duties in this Life, and his Hopes in the World to Come’.

Medwyn initially said ‘in consequence of their youth, [he had] felt inclined to a lenient sentence’ but the boys’ crime was ‘heinous’. He sentenced Alexander Boynes to eighteen months imprisonment, but obviously felt Charles Campbell was the real ‘baddin’: ‘Theft, especially when committed by means of house-breaking and by a person who is by habit [sic] and repute a thief, and who has been previously convicted of theft, is a crime of a heinous nature and severely punishable.’34

It was futile to send his like to a prison which turned young petty offenders into ‘more expert thieves and more hardened criminals’,35 so he ‘could not propose a sentence less severe than transportation’.36

A boy of eleven or twelve who wanted to steal some cotton shifts in order to buy a pie was to return to Aberdeen prison, an ancient tower which reformer Elizabeth Fry described as ‘a scene of unusual misery’,37and wait to be ‘transported beyond seas for the period of seven years’.

Beyond seas for seven years. This was an unimaginable journey and duration for young boys like Charles Campbell and Henry Sparkes. It had been a punishment since Queen Elizabeth, frustrated at the continued crimes of poor street folk despite whippings and burning of a 1 inch (2.5 cm) hole in their right ear, declared such ‘rogues’ ought to face death or be transported with the letter ‘R’ branded on their bodies as ‘incorrigible and dangerous rogues’ to a colony overseas. Two centuries on and England was still looking to rid itself of ‘rogues’ through exile, even if they were victims of hunger or homelessness like Charles Campbell and Henry Sparkes.

No amount of tears or fears could elicit any mercy. After hearing one boy’s mournful plea — ‘I never knew what it was like to have the attentions of a father and mother…I was cast abroad…at a very early age’ — and how he would rather die than be transported, a judge sentenced him to be transported ‘for the term of your natural life’ with a stern warning38:

You speak as if this life were all. Remember, that this life is inconsiderable; it is nothing at all to what is to come after; and if you were to shorten your term of existence by any act of violence, or if you fail to employ the days yet allotted you in penitence for your crimes and preparation for another state, all that you have been suffering for is but nothing as to what you will suffer for eternity.39

Lawmakers and judges saw boy thieves like Henry Sparkes and Charles Campbell as criminals unchecked by irresponsible parents, unwilling to stay on a path of honesty, and unable to be ‘corrected’. One House of Correction governor, George Chesterton, told a House of Commons select committee reformation was ‘utterly hopeless’, as ‘boys brought up in a low neighbourhood have no chance of being honest, because on leaving a gaol they return to their old haunts and follow the example of parents or associates’40 who ‘wait round a prison gate to hail a companion on the morning of his liberation, and to carry him off to treat him and regale him for the day’.41 So the judgment was that ‘they go to a place where they must suffer disgrace and hardship, and where they must lose that which is the most painful to a human being to lose – all hope of liberty’.42

For Sparkes and Campbell, such a place was Van Diemen’s Land. After the North American revolution closed Britain’s dumping ground across the Atlantic, it scanned its remaining empire and chose the Great Southern Land, formerly ‘Terra Australis Incognita’ or ‘the great unknown land’, as its place of exile. Reached only by long and perilous journey and surrounded by ocean at the very bottom of the known world, Van Diemen’s Land was its own perfect island for the condemned, and a hitherto untried system of a government transporting convicted men, women and children to seed a new colony.

Henry Sparkes and Charles Campbell had probably never seen a map that showed their destination, as close to the icy edges of Antarctic as London to Rome. They might have heard of it as ‘Van Demon’s Land’, or that it was somewhere near where Gulliver’s Travels’(1726) author Jonathan Swift had placed Lilliput, his place of greatest imaginable isolation, but leaving the courts of Nottingham and Aberdeen, Sparkes and Campbell could not possibly imagine what lay ahead.