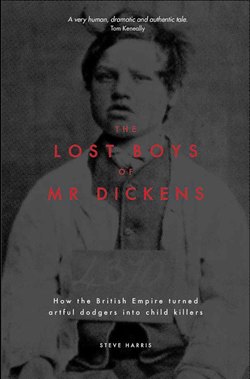

Читать книгу The Lost Boys of Mr Dickens - Steve Harris - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление4

A FLOATING BASTILLE

Even if he has been wicked, think how young he is; think that he may never have known a mother’s love, or the comfort of a home; that ill-usage and blows, or the want of bread, may have driven him to herd with men who have forced him to guilt. For mercy’s sake, think of this before you let them drag this sick child to a prison, which in any case must be the grave of all his chances of amendment.

— Charles Dickens, Oliver Twist

Before Henry Sparkes and Charles Campbell could be transported beyond seas they first had to be transported beyond their known world of Aberdeen and Nottingham to Britain’s first national prison: Millbank Penitentiary, a yellow brown mass of brickwork on the marshy banks of the Thames between Westminster and Chelsea.

Some boys saw Millbank as an esteemed badge of honour. They had grown up coming to regard ‘pluck’ or daring as the greatest virtue in life, their ‘trickery or ‘artful dodges…the highest possible exercise of the intellect’, because honesty was ‘monotonous and irksome’.1 Those who laboured for a living were ‘in plain English, fools’2 when the road of vice was ‘full of boundless joy’, as the House of Lords was told.3

In their own unique code, the greater the risk and crime, the higher the sense of manhood, self-esteem and superiority. Boys like Campbell and Sparkes inhaled their apparent importance and cleverness, pleased with themselves that their court appearances were attended by judges and barristers in wigs and gowns, pressmen taking notes and spectators sometimes paying a shilling. And that, despite their small size, they were held in such dread that society had to place them ‘behind huge massive bars which ten elephants couldn’t pull down’.4

In the fraternity and ‘flash patter’ of the street, there was a clear hierarchy or aristocracy: at the bottom were the ‘pudding snammers’, boys who only stole from bakeries to feed their stomachs; ‘files’ who picked pockets of watches and jewellery were rated higher than those who merely thieved handkerchiefs; ‘sneaks’ who robbed a shop till; ‘snakes’ who wriggled their way into small spaces for house burglaries; ‘bouncers’ who stole while pretending to be bargaining; and the ‘swell mob’ who dressed respectably to camouflage their criminality. Boys transported for life were of ‘greater consequence than the boy who is sentenced to seven years, while the lad whose sentence is a short imprisonment is not deemed worthy to associate or converse with’.5

Dickens visited Newgate not long before Sparkes and Campbell arrived in London, and observed of the young pickpocket boys behind bars:

There was not one redeeming feature among them, not a glance of honesty, not a wink expressive of anything but the gallows and the hulks…as to anything like shame or contrition, that was out of the question. Every boy…actually seemed as pleased and important as if he had done something excessively meritorious in getting there at all…worth the trouble of looking at.6

Even if they were motivated otherwise, it was almost impossible to avoid old haunts and habits. ‘Where else can we go?’ one said, ‘we cannot for our ‘pals’ would torment us to return’.7 Another said: ‘I do not want to thieve if I can get money honestly, but how am I to get it? Will you employ me? Will anybody be fool enough to employ me? Just out of gaol and with no character, just think of that sir, and tell me if I must not thieve!’8

William Miles, who interviewed dozens of boys like Sparks and Campbell in prisons and prison hulks as part of a report to the House of Lords in 1835, concluded: ‘[They] have no sense of moral degradation; they are corrupt to the core; they are strangers to virtue even by name…they are in a state of predatory existence, without any knowledge of social duty; they may lament detection, because it is an inconvenience, but they will not repent their crime. In gaol they will ponder on the past, curse their ‘evil stars’ and look forward…to their release, but their minds and habits are not constituted for repentance.’9

Their only ‘social duty’ was their own ‘artful dodge’. Society had its laws, watchmen and police, but food and thievery trumped starvation and honesty, and boys marched to a ‘we beat you’ drum10 in a life of taking chances. The chances of finding something to rob, being seen and detected, being prosecuted, being convicted, and a modest sentence. Chance was their anthem, with ‘every hour of their freedom…uncertain…in a kind of lottery adventure’.11

In this lottery of life it was merely ‘evil stars’ and bad luck if they were detected and punished, imprisonment ‘merely another step in the ladder of their sad destiny’.12 For Sparkes and Campbell their ‘evil stars’ saw them moving up the juvenile aristocracy from houses of correction to Millbank, a premier college of criminality and a rite of passage for those destined for Van Diemen’s Land.

Taking its name from a mill belonging to Westminster Abbey, the prison opened in 1816 as London’s largest, a £500,000 English Bastille lauded as the greatest in Europe for its revolutionary panopticon (Greek for all-seeing) design allowing centrally positioned guards to provide constant surveillance over 1500 transportation prisoners in six star shaped blocks.

The sights, sounds and smells of the multi-turreted stone fortress never left convicts who had passed through. Sitting on marshland and surrounded by a stagnant moat, its cold, damp and gloomy passages fuelled cholera, malaria, dysentery and scurvy. The ‘revolutionary’ Millbank was soon condemned for its design and conditions. The new penal science of dark, silent cells and isolation was, according to some newspapers emerging as a conscience voice, an abomination, an ‘unnatural…modern cruelty devised to impair the health, destroy the constitution, and obliterate the mind’.13 Reforming journalists described Millbank as ‘one of the most successful realisations, on a large scale, of the ugly in architecture, being an ungainly combination of the madhouse with the fortress’.14

But thousands of small boys endured this madhouse-fortress. Reforming journalist, social researcher and future Punch magazine founder, Henry Mayhew lamented ‘the little desperate malefactors…many are so young they seem better fitted to be conveyed to the prison in a perambulator than in the lumbering and formidable prison van’.15 One governor even recalled ‘a little boy six and half years old sentenced to transportation’.16

The Morning Chronicle — the first newspaper to steadily employ Dickens — had earlier declared ‘there is but one remedy — to place as much gun powder under the foundation as may suffice to blow the whole fabric into the air’.17 But sheer numbers of prisoners meant it could not be blown up, nor could little boys who veered from the ‘right path’ be spared.

Under pressure from reformers, some officials proclaimed they were endeavouring to better classify and manage prisoners based on age, criminal record, and behaviour, and take greater account of the capacity of young boys without education or moral guidance to understand the consequences of their thievery or falling under the influence of older boys and men. But the reality was a shadow of any stated intent, and houses of correction and prisons commonly held ‘thirty or forty [to] sleep together; and as they are, for young ones, of the very worst description of offenders, the consequence may easily be imagined’.18

Millbank was no exception. In between what Dickens described as a ‘melancholy waste’19 of ‘making money from old rope’ — picking apart thick strands of oakum, the old tarred rope fibres used between planks of a ship and sealed with hot pitch, for the prison to sell for re-use or other hard labour tasks — younger, smaller and weaker boys had to survive the same code of self-interest and self-preservation they had known on the street.

Bigger, more hardened boys, known as nobs, quickly educated or intimidated others to remain silent about their bullying, theft of food, corruption or sexual abuse. Under the code of the nobs, and the ancient code of ‘honour among thieves’, staying silent offered the best chance of avoiding punishment. Boys also had to obey a strict official code that, by the late 1830s, saw more younger offenders kept in silence and separation to prevent ‘contamination’ and allow longer periods of ‘reflection’ in the hope they would become more repentant. Breaking the silence, by word or gesture — even a meaningless smile to a fellow inmate — risked being strait-jacketed or shackled for days; sometimes soaked in water, beaten or whipped; or being ‘broken’ by spending time in ‘solitary confinement like a dog in a kennel’.20

Some boys baulked at the two codes of intimidating wardens or fellow boys and the appalling conditions. ‘Prisoners showed their resistance in various small ways such as working as slowly as possible, talking during their work, and stealing other prisoner’s products and passing them as one’s own…prisoners also threatened or bribed guards and other prison workers.’21 But some were broken: ‘Few days passed but some desperate wretch, maddened by silence and solitude, smashed up everything breakable in his cell in a vain rebellion against a system stronger and more merciless than death.’22

Millbank Prison Mayhew. Image courtesy Alamy Stock Photos, A67BWD

The ‘modern’ imposition of ‘darkness’ was a mental punishment seen to be more painful than the physical, and it would follow convicts all the way to Port Arthur and Point Puer. Dickens was appalled when he witnessed prisoners in America never looking upon a human countenance or hearing a human voice:

He is a man buried alive, to be dug out in the slow round of years, and in the mean time [sic] dead to everything but torturing anxieties and horrible despair…wasted in that stone coffin…hears spirits tempting him to beat his brains out on the wall.23

Dickens condemned it as ‘cruel and wrong’ and was supported by the Illustrated London News, the world’s first illustrated weekly news magazine, which called for an end to such ‘experiments…[that] degrade the sacred name of justice…make the law monstrous…a disgrace and sin’.24

Unlike some, Sparkes and Campbell did not have to endure Millbank’s experiments for a long period. Five weeks after his sentence in Nottingham, Sparkes was among those removed by longboat from Millbank to the prison hulk Euryalus in February 1839. Campbell followed the next year, two months after his sentence in Aberdeen.

Prison hulks, another penal experiment and expediency, were introduced in 1776 after the American Revolution. The decision was initiated as a ‘temporary’ two-year utilisation of unseaworthy and de-masted Naval and commercial ships as floating prisons, to help cope with the rising tide of prisoners and overcrowded gaols.

The first prison hulk was the Justitia, named for the Roman personification of justice and moral force, widely portrayed as Lady Justice with a blindfold signifying the law being applied with no regard to wealth or power. But few of wealth and power were to be found on the Justitia and what became a fleet of hulks at Chatham Thames estuary in north Kent — where Dickens spent some childhood years and incorporated some of his memories into Great Expectations — and Sheerness, Deptford, Woolwich, Gosport, Plymouth, Portsmouth and Cork. The ‘temporary’ hulk fleet lasted eighty years.

Some boys would have anticipated that after stints in Houses of Correction, regional gaols and a few months at Millbank they would soon be leaving such misery behind, about to embark on a voyage to a new and perhaps better opportunity — even an adventure. But their hopes were dashed, Sparkes and Campbell spending seven long months on Euralyus at Chatham in conditions that would cause even a resilient and optimistic boy to question his sentence to the other side of the world.

Gloriously launched by the British Navy in 1803, Euryalus was named after one of the Argonauts, the mythical Greek band of heroes accompanying Jason in his search for the Golden Fleece. As a 36-gun frigate, the ship had an illustrious naval history in the Napoleonic Wars accompanying Lord Nelson at the 1805 Battle of Trafalgar, and the War of 1812, but there was nothing heroic or golden about it as an aged, de-masted prison hulk.

The outline of dismembered masts in the gloomy Thames mist might have reminded Sparkes and Campbell of the gibbets which horrified boys in Nottingham and Aberdeen. The hulks certainly had their ghosts: death rates had been as high as one in four when the first hulks were employed and were still one in ten by the turn of the 19th century. They were the pits for the unpitied, the physical and psychological conditions so bad some prisoners averred a preference to hang rather than endure what would come to be seen ‘of all the places of confinements that British history records…the most brutalising, the most demoralising and the most horrible’.25

Sparkes and Campbell were a little more fortunate than their predecessors, who were held in irons alongside older youths and adults before calls for better protection of children led to the Captivity becoming the first hulk set aside exclusively for boys in 1823. But it was deemed unsuitable and, after two years, was replaced by the Euryalus, a ship which a Select Committee on Gaols and Houses of Correction also recommended in 1835 be abandoned immediately. But authorities did nothing for another seven years, during which another 2500 boys under fourteen, some as young as eight or nine, were hustled aboard.26

Regardless of age, such boys were seen by authorities in simple terms: as prisoners who were no longer entitled to walk in the land of their birth and were being banished for the ‘good’ of the country, and perhaps for themselves.

The conscience of Britain was beginning to be stirred by social reformers like Elizabeth Fry, Quakers like Samuel Hoare, evangelical politicians like Thomas Buxton, lawyer-authors like Thomas Wontner, and reporter-authors like Charles Dickens, Henry Mayhew and George Reynolds. But authorities steadfastly wanted to cleanse themselves of unwanted ‘vermin’, drain away the ‘dregs’ and win the war on ‘wickedness’.

Young boys on the frontline were not spared, judged more on reputation and looks than the seriousness of their offences and denied benefits of understanding or mercy. So as two casualties of the war, Sparkes and Campbell had to be held in what a Royal Navy captain described as a ‘floating Bastille’.27

Prison-ship in Portsmouth Harbour, convicts going aboard, illustration and etching, Edward William Cooke, 1828. Image courtesy National Library of Australia, nla.obj-135934086.