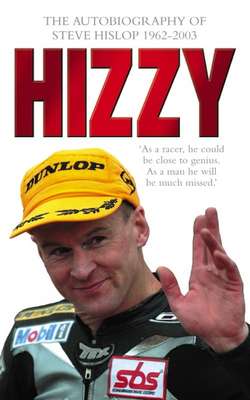

Читать книгу Hizzy: The Autobiography of Steve Hislop - Steve Hislop - Страница 8

4 Tales from the Riverbank ‘I poached salmon and sold them to pubs to help pay for my racing.’

ОглавлениеMany people have asked me why I didn’t turn my back on bike racing when my brother was killed and it’s still a difficult question to answer.

I think I just had an inbuilt desire to achieve something in my life and racing bikes seemed the only way I could do that. I certainly never blamed racing for Garry’s death as it was his choice to race and I never hated the sport because of what it had taken away from me. Bikes have always been part of my life and I continued to ride them after Garry died just as I always had done.

When I went to the inquest I learned that my brother had been leading the 350cc race and had broken the lap record before he crashed. There was a hairpin corner on the track and it was flooded from heavy rain in the morning so the organizers reshaped the corner using road cones. When it dried, the track surface became silty and dusty in the same way as a puddle dries when it’s stopped raining. Garry must have just clipped that silty surface next to the road cones and was high-sided off the bike – racing speak for being thrown over the top of the machine. Instead of landing relatively harmlessly as he would have done nine times out of 10 in such an accident, he landed on the back of his head and the back of his helmet caved in causing Garry to fracture the base of his skull. Ironically, that was the last race ever to be held at Silloth.

Garry is buried in Southdean cemetery, near Chesters village, right next to my dad: they died just three years apart. My dad was 43 and my brother just 19. Each headstone has a little motorbike engraved on it and Garry’s stone has an inscription reading, ‘He died for the sport he loved.’ Apparently it was me who asked mum if she would have those words engraved on it although I can’t really remember asking her.

Just before he died, Garry was being tipped as one of Scotland’s most promising riders and I’m sure he would have achieved similar results to me had he lived long enough. He was keen to turn professional in 1983 but, sadly, we’ll never know just how good he could have been. As I said, I don’t blame racing for what happened but I have often questioned the existence of a god since I lost my brother and father. What kind of god would take them away from me?

To cheer myself up a bit, I decided to go to the Isle of Man in June for a three-day break to watch the TT races but little did I know then that trip would change my entire life.

My first ever trip to the Isle of Man had been to the Manx Grand Prix in 1965 when I was just three years old and my dad took me over to support Jimmy Guthrie Junior. I went again to the Manx in 1975 but my first trip to the actual TT was in 1976, which was the last year the races counted as a round of the world championship. I watched my very first race from the Les Graham memorial near Bungalow Bridge. I could hear the bikes coming towards me from miles away because they were so loud back then; they were pure race bikes with pea-shooter exhaust pipes, not just glorified production machines like they race today. John Williams on the Texaco Heron Suzuki was the first rider I remember seeing and he was quite simply the fastest fucking thing I had ever seen in my entire life. He just blew my mind. Unbelievable! He did a 112mph lap that day which was the first sub-20-minute lap ever of the TT as far as I remember. But because he went so fast, he ended up running out of fuel and had to push his bike for a mile at the end to finish the race!

I was pretty much hooked on the TT from that moment on and went back there again in 1979 when I was 17 with Wullie Simson and another friend called Dave Croy. I helped Wullie and Dave in the pits, working for a rider called Kenny Harrison so it was my first real hands-on experience of the event. As it turned out, Wullie and Dave were the guys who helped me for years when I started racing, right up until I got involved with Honda. They were both a great help to my career.

Anyway, as I said, after Garry was killed I didn’t race very often and I certainly had no intentions of ever becoming a professional racer. I had also never really thought about racing on the Isle of Man myself. However, that all changed when I went to the 1983 TT races, this time with Wullie and a man called George Hardie who later was to become my mum’s partner and still is as I write this.

We were sitting on the banking just after the eleventh milestone munching on our pieces (Scottish for sandwiches!), enjoying the fresh air and watching the traffic go by before the big Senior Classic race got underway. Like everyone else around the course, we had our little transistor tuned into Manx Radio to listen to the race commentary, so that we knew who was who and what was going on. The men of the moment were Joey Dunlop and Norman Brown who are both tragically no longer with us. Norman was killed while racing in the British Grand Prix at Silverstone just a couple of months later and Joey, as everyone knows, lost his life in an obscure race in Tallin, Estonia in 2000 just a month after completing his famous TT hat-trick.

I could hear the bikes setting off over the radio but it was some time before I could actually hear them on the road for real. Eventually, I picked up the sound of Norman Brown’s Suzuki RG500 engine screaming along the mile-long Cronk-y-Voddy straight towards us, then he blasted into view and shocked the life out of me. Having seen the normal road traffic going past for the last couple of hours, words cannot describe the difference in speed as Brown went past our spectator point. Fuck me, he came through the corner at the end of Cronky down towards the eleventh milestone, lifted the front of the bike over a rise in the road, braked hard and back-shifted two gears before changing direction and blasting off towards Handley’s. He was going so fast that he almost blew me off the bloody banking.

Joey Dunlop was hot on his heels on a Honda RS850 and he had it up on the back wheel too and was pushing every bit as hard as Brown. My reaction was, ‘For fuck’s sake!’ I just couldn’t believe that anything on earth could go that fast. I was completely blown away with the whole spectacle.

In those split seconds that it took Brown and Dunlop to hammer past me, my life had changed forever. I determined there and then that if I never did anything else in my meaningless life, I would try to ride round the TT circuit like those boys. My mind was totally made up.

Having finally realized what I wanted to do with my life, I wasted no time in going about it when I got back home. As an amateur, I decided that my first attempt on the Mountain course should be at the Manx Grand Prix, which was being held in September, just three months away. I didn’t have long to go from being a TT spectator to a Manx GP competitor.

The bike was not a problem, because I had already bought Cookie’s Yamaha TZ250E for £800 and had enough spares to convert it into a 350 as well. But somehow I had to find money to fund the trip as well as getting hold of a van and getting all my entries organized. I was granted a Scottish national licence with no problem because I had a few races under my belt, then I blew £200 on a new set of leathers and then I had to save almost every penny of my meagre £36 a week salary to fund the trip.

I soon realized that wasn’t going to be enough cash so I started selling things as well. First to go was my father’s 350cc Aermacchi racing bike which netted me around £2000 then I sold my beloved Ford Escort Mexico – a mega car which I was really proud of. I had swapped it for the car I was spraying on the day Garry was killed but, true to form, I put the bugger straight through a hedge within a week. At least I was consistent. After the crash I spent a lot of time working on it and buying new parts but I needed cash to go racing so I sold it at a loss because I was so desperate. So for the first time in years I didn’t own a car but being a bike racer is like being a junkie; you’d sell your own granny to get what you need.

I even had to change my lifestyle to save money. I stopped going out to the pubs with my mates and refused to go for a pint even when they called round to the house. When I wasn’t working on my bikes, I just stayed in and watched television. I even knocked back the chance to go to Ibiza on holiday with the rest of the lads but it never got me down because I was so focused and all I thought about was lining up on the grid on the Isle of Man.

When I filled in the entry forms for the 350cc Newcomers race and the 250cc Lightweight event at the Manx the only person I told was Wullie Simson because I knew most people were against me racing after what had happened to my brother. I felt a bit sneaky going behind peoples’ backs and not telling my mum or anyone else about my plans but that’s the way it had to be; I really didn’t want to upset anyone but I knew I had to race. I even prepared my bikes in secret and just told anyone that asked that I was doing overtime at the garage.

But it wasn’t long before my little secret got out thanks to the race organizers. Once I’d posted off my entry forms I’d forgotten all about them until I came home from work one night and the shit really hit the fan. My mum and stepdad looking thoroughly miserable confronted me. I just said, ‘All right? How’s it goin’ folks?’ but Jim’s response was to slap a postcard down on the table in front of me and shout: ‘What the hell is this?’ It was the confirmation of my race entries written on a bloody post card for the whole world to see! Shit.

‘Dear Steve, just to confirm we have received your entry for this year’s Manx Grand Prix.’ I thought ‘Fuckin’ hell, I’ve been rumbled here.’ Jim went absolutely apeshit screaming at me, ‘How can you do such a thing to your mother?’ giving it all that guilt-trip bollocks. I explained it was just something I had to do and defended myself as best as I could but it was obviously falling on deaf ears. My mum and Jim continued arguing and then she said something I’ll never forget. He was rattling on about me bringing more grief into the house after Garry had already brought enough when my mum shouted, ‘Why the hell should Steve live his life in the shadow of someone else?’

It was a brave thing to say. I mean, I know I’m a selfish person for doing what I do (as I think all bike racers must be) but my mum saw beyond that and recognized my real passion for racing. Jim hated the idea of me racing but I never expected him to understand and I didn’t care about his opinion anyway. But I really appreciated what mum said because she obviously realized it was unfair to deprive me of something I wanted so badly just because my brother had been killed doing the same thing. We don’t stop driving cars because someone else has an accident, do we? To me, bike racing was no different.

My mum was the only person who didn’t try to discourage me from riding bikes after Garry’s death. Everyone else, aunties, uncles, colleagues, the whole lot of them said, ‘Well, that’ll be the end of the racing in your family then, Steve’, but my mum was different and I still respect her for that. She even walked out on my stepdad for a while when I went to the Isle of Man because they had been arguing so much about me racing and she refused to side with Jim when he wanted to stop me.

In a bid to get in shape for my Island debut, I cycled the 12 miles every day to work and back on a borrowed pushbike for six weeks. Some nights it was freezing cold and pissing with rain and just thoroughly miserable as I was cycling home and my hands would be red raw with cold but I just kept an image of Joey Dunlop and Norman Brown in my head and that drove me on.

I entered some races at Knockhill in Fife a few weeks before the Manx just to make sure the bikes were going OK. I still had the little 125cc bike that Garry had ridden and I wanted to sell it so I figured a good race result would also be a good advert for the bike. I finished second to Roddy Taylor who was Scottish champion at the time so I was quite pleased with that and managed to sell the bike as well. I was then lying about fifth or sixth in the 350cc race when I fell off and I remember being really pissed off about that because I scuffed my brand new leathers that I’d bought specially for the Manx!

Anyway, with everything packed up in the van, Wullie Simson and I caught the ferry from Heysham and four hours later we were on the Isle of Man and I was itching to get out onto the course to start learning it. One of the questions I still get asked a lot is how I learned the TT course so well. There’s no real secret, it’s just about putting the time in and having an aptitude for it. I’m very good at learning things like that and within a couple of laps of any foreign circuit, I was usually on the pace. But I know of some good riders who went to the TT and just couldn’t get their heads round the course.

The TT is different to learn compared to short circuits because it’s got well over 300 corners and you need to know where every one of them goes, where every bump is, every drain cover and every rise in the road. You need to find the quickest but safest lines to take as well as knowing where all the damp patches tend to linger after it has rained. You must know where the wind is likely to get under the bike and lift it or blow you sideways. You must know your braking points for every corner on different types of machine and you’ve got to know what gear to be in for them all too to get the optimum revs, grip and drive. On top of that there’s cambers to learn, both converse and adverse, and loads of little tricks to gain time like using kerbs or bus stops to run wide, meaning you can take certain corners faster. And when you’ve learned all that, you need to find out how you can go quicker still by shaving off fractions of a second each lap. In short, it’s the most difficult and demanding course in the world to learn and you never, ever stop learning it. There’s never been and never will be a perfect lap of the TT.

But I had a bit of a head start as a kid because I used to sit in the back of cars and vans when my dad and Wullie Simson went round learning the course themselves. I listened carefully to everything they said about each corner and where the apexes and peel-off points were and I learned an awful lot that way. It was just through boyish enthusiasm because I never thought I’d ever race at the TT but somehow all of that knowledge stuck in the back of my mind and I put it all to good use when I eventually did come to race there.

I can’t actually remember it but my mum tells me that I used to be able to recite the main points on the TT course when I was just five years old because I’d heard my dad and all his pals talking about it so much. When I used to sit on the arm rests of the sofa with Garry as kids playing at racers apparently I’d do a running commentary, ‘And Jimmie Guthrie’s coming round Quarterbridge and heading on out to Braddan’, or, ‘He’s coming down the Creg and heading for home.’ Mum says my dad used to sit gobsmacked listening to me and wondering where the hell I’d got it all from!

After I’d progressed from sofa racing and actually got onto the TT course for real I wasn’t one of those guys who did 300 laps in a van before practice. In fact, I only ever did about 12 complete laps on my own before lining up for the first practice session. Ten times TT winner and 15 times world champion, Giacomo Agostini, went to stay on the Isle of Man for two weeks before he first raced there and spent six hours every day going round and round the track to learn it. I never had to do that.

The first lap I ever did on a bike was in 1983 after watching Joey and Norman Brown in that Classic race. Jim Oliver had a little Yamaha RD250 with him and he let me do one lap on it after the race before we all went out for some beers that night. It was a good time to go round the track because most people had already been there for two weeks and had had their fill of laps so it was pretty quiet. I made sure I took a stopwatch in my pocket and started it off at Quarterbridge then went for it as fast as I could, especially over the mountain section where there’s no speed limit, another unique feature of the Isle of Man. Boy, I was really going over there, absolutely flat-out all the way on that little LC. I rode back round to Quarterbridge and stopped my watch; it read 32 minutes, which equated to a lap average of 78mph. I know that precisely because I still have a five-year diary from that period and I entered my time in it! That was going some for open roads so I was quite chuffed with myself – after all, some people still can’t do that in a bloody race!

These days, there are so many videos of on-board camera laps of the TT available to buy that a new rider could learn the course reasonably well before ever setting foot on the Isle of Man but they didn’t exist when I started out. I actually made one of those videos in 1990 called ‘TT Flyer’ and managed to clock the first ever 120mph lap with a camera on board. It caused quite a sensation at the time. I even wrote a book on the course itself a few years back explaining the right way to take every corner – that’s how well I know the place!

Speaking of on-board camera footage, I remember getting passed by Joey Dunlop a few times in my first practice week at the Manx, as he was recording footage for the ‘V-Four Victory’ video and had a huge big camera strapped to the tank. These days the cameras are so small you don’t even know they’re there but in 1983, it was like having Steven bloody Spielberg sitting on the tank with a full camera crew in tow! Anyway, Joey passed me so many times that I thought there was three of the little buggers – I didn’t realize that he was continually stopping to adjust the camera!

I broke down at Lambfell just before the Cronk-y-Voddy straight on my first ever practice lap – the bike just went flat and died on me. But I had come prepared and pulled out a little girlie purse that was riveted to the inside of the fairing and contained fresh spark plugs and a plug spanner! Sure enough, one of the plugs on the bike was fouled up so I changed it, bump-started the bike and was off on my way again. That’s the sort of DIY job which keeps you going on the Island and it was the norm back then as it probably still is now for riders who aren’t in big teams.

But I only got as far as Ballaugh Bridge on the same lap then the bloody thing died on me again. This time the big end was gone and it definitely wasn’t going any farther so my session was over. But it wasn’t all bad, as that’s when I first met the famous Gwen from Ballaugh. She’s spent years looking after riders who break down anywhere near the renowned humpback bridge and she always had pots of tea, cakes, biscuits and toast at the ready. You’ve got to remember that practice starts at 5am on the Island so I was really ready for a breakfast! So I ended my first practice session in the lap of luxury eating breakfast and drinking tea in Gwen’s house which was a lot better than what I’d have got back in our van. Ever since then, I always waved or wiggled my foot at Gwen just to say hello during a race, no matter how hard I was riding. I never knew when I might need her hospitality again.

The rest of practice week went okay and I eventually hit upon a pretty good way of learning the course better. Instead of trying to follow the newest young hotshot who may have been quick but reckless, I decided to tag on behind the older boys riding classic bikes. I figured that they had all probably ridden the course for years and would know their way around intimately, even if they weren’t going that fast in a straight line. It proved to be a good idea as their lines were spot-on so I really learned a lot by doing that. I remember I had to roll off the throttle on the straights so as not to pass them then I’d try to follow them through the twisty bits. But they usually lost me so I’d have to hang around until another rider came along and try to follow him for as long as I could.

The buzz of riding the Mountain course was every bit as awesome as I’d hoped for. Racing flat-out on real roads without worrying about tractors, coppers or anything coming the other way is an amazing thrill and that’s what attracts riders to the TT year after year despite the dangers. My favourite sections were from Ballacraine to Ballaugh and then from Sulby Bridge to Ramsay. I never enjoyed the mountain section as it’s just so bleak up there. I think I was put off from the start when I broke down there (again) later on in my first practice week and had to wait for hours for the van to pick me up. Not a good place to be stranded.

I was more like Joey Dunlop in that I loved to be in among the trees, hedges and stone walls. It was fantastic racing between them at such high speeds and that’s where I always made up time on the other guys who maybe backed off a little through those parts. Those sections took a lot more learning as well, which is more pleasurable in the end because it’s more of a challenge and very rewarding when you get it right.

The Newcomers race was on the Tuesday and it was the first race of the week as well as being the first of my Island career. I was 21 years old. Everyone thought Ian Newton was going to win because he had been quickest all through practice week but he was pushing himself too hard and he ripped the bales off a stone wall at the Black Dub on one lap when he clouted them with his bike. He was riding out of his skin and luckily, for the sake of his life, his bike broke down and that was that.

The race became a four-way scrap between me, Robert Dunlop (Joey’s younger brother), Ian Lougher and Gene McDonnell. Gene would later die in horrific circumstances when he hit a horse on the course at full speed in 1986. The horse had panicked and jumped on to the track when a paramedic helicopter had landed in a field to pick up Brian Reid who had crashed at Ballaugh and broke his collarbone. Both Gene and the horse died instantly. It was a harsh reminder of the bizarre hazards of the TT.

Race-wise, I had my fair share of problems despite all the preparation Wullie and I had done on the bike. After just five miles my back brake faded to practically nothing, then the wadding in my exhaust blew out making the bike go flat and as if that wasn’t enough, the chain started seizing up because it was too hot. The vibration from that in turn split the frame in some parts and on top of that my fairing had worked its way loose and was hanging off by the end of the race!

But despite all my problems I ended up finishing second to Robert Dunlop with Ian Lougher in third place. All three of us went on to have great TT careers and currently have 22 wins between us. As I write this, Robert and Ian are still racing there so they may well rack up some more wins yet.

Second was a brilliant result for me because I hadn’t expected to achieve anything when I went to the Island – I just wanted to ride the course and enjoy myself. As I said before, the bike was hanging in pieces at the end of the race so I was really lucky to get a finish at all and I even put in a lap at 103.5mph which was pretty quick back then for a 350cc machine.

The only disappointing thing was that I didn’t get a trophy. Only the winner of the 500cc class, the 350cc class and the 250cc class (all classes ran in the same race) got replicas. I just got a little finisher’s disc, which was a bit of a bummer. But I did get a trophy for my eleventh place in the 250cc event later that week which kind of made up for things even though the bike was a total nail – I could have kicked my bloody helmet round the course faster. But I had a great night at the presentation ceremony with Ian Lougher. We got totally legless and I remember pissing myself at him trying to dance to UB40’s song Red Red Wine, which was in the charts at the time. It was hilarious. Ian’s much better on a bike than he is on a dance floor!

When I got on the ferry and headed for home I started thinking about how much I had enjoyed myself over the last couple of weeks. The racing, the nights out, the atmosphere; it was just a great event and I decided there and then that I had to do it again the following year so I started saving for the 1984 event as soon as I got back home. I didn’t even consider racing a full season on short circuits because all I wanted to do was race on the Isle of Man again. Anyway, I couldn’t afford to do a full season with the money I was making.

Looking back now, I wish I could live my life over again. Those were good years when I was still young that I just pissed away, waiting for the Manx and the TT to come round again. What a bloody waste! Had I committed myself fully back then and somehow found some sponsors, who knows where I could be now? I certainly feel as if I should be sitting here with a couple of world titles under my belt, either in World Superbikes or Grand Prix but racing’s full of ‘ifs’ and ‘buts’, so I try not to dwell on it too much.

I did one more race at East Fortune at the end of 1983 and finished sixth on the 125 but that was it for the year. So I just plodded on with my job in the garage over winter, rode my Yamaha DT175MX trail bike to keep my hand in and daydreamed about racing in the TT.

I did, however, have one other way of getting an adrenalin buzz when I wasn’t racing – poaching! For years, my mate, Rod Heard, and I had been mastering the black art of illegally catching salmon and by this point, we were experts. My upbringing on the farm with all the fishing and sneaking up on crows to shoot them had made me a natural at poaching. I either used a shark hook for the job or sometimes I made my own hooks from an old pitchfork. I remember bending and forging specialized hooks in the garage just for poaching. We called them ‘cleeks’ where we came from and there’s a definite knack to using them but seeing as I started poaching when I was about 10 years old, I had mastered it. I even put motorbikes to good use when it came to poaching because I made a huge halogen floodlight which I powered with a bike battery!

I remember on one occasion, when I was about 13, I was hanging over the edge of a banking by the river and looking underneath the overhanging riverbank. There was a huge salmon in there just snoozing with its tail lightly swishing so I grabbed my cleek, held onto a tree and stretched out over the river as far as I could to get some leverage. I thrust the cleek into the ‘tail wrist’ of the fish (between the bones before the tail fin) and then all hell broke loose. Fuck me, the thing nearly pulled me right off the bank and into the water it was so strong. With a massive effort and not a lot of dignity, I managed to get it out of the water and onto the bank. When we finally got it home and weighed it, it was 11 pounds (or five kilos in today’s money) which is fairly big for a salmon.

Problem was, it was so big I couldn’t get it home on my pushbike so I had to conjure up another way of getting it onto the kitchen table. I hid the fish then walked into Bonchester village and rummaged through a few bins looking for empty lemonade bottles then took them to a shop, got about 20 pence back for them and used the money to call my dad from a phone box. ‘Dad, I’ve caught a fish but it’s a bit on the big side. Can you bring the car to take it home?’

So dad turned up, threw the salmon in the boot, and off he went with me peddling home after him. I sort of got into trouble that night because my mum and dad knew I had been poaching but at the same time, dad was chuckling a bit. After all, his son had proved his resourcefulness and there was a bloody great salmon for the whole family to eat, completely free of charge.

I only poached occasionally as a kid and it was mostly for laughs but by the time I was in my late teens, my mate Rod and I were poaching far more frequently. By then we had our own cars to transport the fish so we caught lots of them and started selling them to local pubs who would then serve them up as bar meals. It was a nice little earner.

We got chased many times over the years by water bailiffs, the police and various farmers but one night in particular stands out. We had caught about 16 salmon (which a top angler couldn’t even dream of doing on a two-week fishing holiday) and left each one hidden under a different tree while we caught more. That way, anyone turning up wouldn’t see a whole mound of fish, which would really have given the game away. Besides catching fish from under the overhanging riverbanks or ‘hags’ as we called them, we would wade into the river up to our waists with a torch because the fish were drawn to the light and stayed in it when you shone it on them. Then we’d simply hook them with our cleeks and throw them on the bank.

It was important to never wear Wellington boots because we soon learned we couldn’t run fast enough in them when we were being chased. Waterproof trousers were a no-no too because they were too heavy for running when they got wet and tracksuit trousers were just as bad. So it was jeans and training shoes only; after all, getting soaked was better than getting caught. We might have got away with it as kids but poaching is a serious offence when adults are involved.

Anyway, that night we were doing fine until we saw lots of spotlights heading straight for us. When that happened you forgot the fish and ran like buggery. We got as far as we could on our legs then dropped to our hands and knees and scrambled through ditches and bogs keeping as low as we could out of the spotlights. It was like a scene from The Great Escape! It was about nine o’clock and pitch black and I remember lying in a ditch watching all those cars and vans and all the commotion as the ‘lynch mob’ tried to find us. We were absolutely shitting ourselves.

Eventually, we made our escape down a railway line, crept into Rod’s house and got changed out of our wet clothes and sat about trying to look innocent in case there was a knock at the door. Rod’s mum thought it was all quite funny and she eventually took the dog for a walk to see if there was anyone still down by the riverside. When she said there was no one there we grabbed our torches and went back to try and find the fish that we’d hidden but every one of them was gone. Bastards! We had done all the hard work and they’d pissed off with our fish. How can you own fish swimming in a river anyway? I could never understand how taking fish could be a crime so I just took them. They’re as much mine as anyone else’s.

On most other nights though we did pretty well and managed to make some decent cash from selling our catch to local pubs. It’s fair to say that more than one customer has enjoyed a nice bar lunch of poached salmon (and I don’t mean the way it’s cooked) in a Borders pub without knowing it! Probably paid through the nose for it too.

Mostly, Rod and I used the extra cash to pay for petrol to arse around in our cars but I’m sure that sometimes the savings I had in my bank to go racing were boosted by my poaching activities. I guess I must be the only bike racer ever who poached salmon to help pay for racing! Just a shame I never managed to catch enough to fund a full World Superbike season.