Читать книгу Hizzy: The Autobiography of Steve Hislop - Steve Hislop - Страница 9

5 The Flying Haggis ‘The sport which took my brother’s life actually gave me a life.’

ОглавлениеMany people, including fellow racers and team bosses, have criticized me over the years for not trying hard enough if my bike’s not set up properly, and that stems from my training as a mechanic when I was a young lad.

I’ve always prided myself on being meticulous when it comes to setting up or fixing bikes, whether they were mine or someone else’s; I suppose in that sense I’m a bit of a perfectionist. So if a team expects me to ride a bike which isn’t handling properly or is unreliable or just plain uncompetitive, they’ve got another think coming. Why should I risk my neck on a bike which isn’t working properly and which could pitch me off at any second? It’s my bloody neck, no matter how much I’m getting paid to lay it on the line, and I won’t risk it unnecessarily to gain a position in a race because racing’s really not that important. Don’t get me wrong, if I’m feeling comfortable and confident on a bike I’ll push as hard as anyone out there but only if the machine’s right.

Maybe that’s been a big downfall in my career and it’s certainly caused some friction within teams I’ve ridden for, but that’s just the way I am. A commercial pilot wouldn’t take off in a plane if he knew it was faulty so what’s the difference with a racing bike?

I’ve never been a big crasher and that’s partly because I refuse to push bikes which aren’t up to it but I’m certainly not afraid of crashing – it’s all part of the territory in this sport and you have to accept that. But many accidents are avoidable so, if I can, I avoid them. Some team managers have complained that my team-mates seem to manage to get decent results on an identical bike to the one I’m riding when it’s not working right, so why can’t I? But that same team-mate was usually riding by the seat of his pants, crashing a lot and taking all sorts of risks just to get the occasional decent result. To me, it makes much more sense to work on getting the bike right and then the results will follow.

And it’s not that I’m a quitter either, as some people probably think. I’ve heard people say, ’Oh, Hislop will chuck the towel in if things aren’t going well,’ or, ‘He’ll come apart like a cheap watch when the pressure’s on.’ But it’s total bullshit. I will try everything I know to get a bike set up properly and I’m prepared to have some scary moments while I’m experimenting with different set-ups, too, if that’s what it takes. The 1994 TT is a good example. The Honda RC45 I was riding that year was a real handful round the Island and I don’t know how many near misses I had in practice, but I worked away at it all through practice week until I had it a bit more under control. My team-mates, Joey Dunlop and Phillip McCallen, had too many other bikes to set up so I concentrated on the RC45 to try to find settings for all of us. Both Joey and Phillip were happy enough with my set-up advice and Joey even borrowed my spare set of forks for the races. I haven’t seen them since but, knowing Joey, they’re probably still lying around in his pub somewhere! The point is that initially the bike was so bad that Joey didn’t want to ride it and that’s really saying something because Joey could ride anything round the TT. But I persevered because I thought there was light at the end of the tunnel and in the end I won both races on it.

It was the same with the Norton in 1992. It was an absolute nightmare to ride at the beginning of practice week, bucking and weaving everywhere but I stuck with it, too, and got it going right for the Senior class race which I won. But sometimes bikes are beyond help and I flatly refuse to risk my life on an under-powered or poor-handling bike just to get a sixth place. No way!

I certainly had plenty of time to get my Yamaha ready for the 1984 Manx Grand Prix because it was the only race I did all year except for one outing at Knockhill that I treated as a shakedown session for the Manx. My bike was a 1978 model, which was obviously getting a bit long in the tooth, so I spent a good bit of cash upgrading it that year. I bought an alloy frame to make the bike lighter and new bodywork to make it look more modern, together with some other smaller parts. It ended up looking really good, even though it was a bit of a hybrid. I really enjoyed my race at Knockhill. It’s always been a good track to ride on smaller bikes but I think it’s too tight and twisty for modern Superbikes so I’ve come to dislike it in the last few years, even though it’s my ‘home’ circuit in the British Superbike championship.

Wullie Simson came over to the 1984 Manx with me as did Wendy Oliver, who I was seeing quite seriously at the time and who was the daughter of Jim Oliver, my boss. I had entered the 350 in the Junior and Senior events and practice went okay apart from some problems with my new frame, which broke a couple of times. I got it welded up again but I wasn’t sure if it would last race distance. Sure enough, I was running in about third place in the Junior race when the bike started mishandling badly because the frame had broken again so I was forced to pull in and call it a day.

You never stop learning at the Isle of Man. Every time out on the bike, there’s something different whether it’s the weather, changes to the road surface or any number of other things; I was still learning that course the last year I rode it in 1994. I even used to lie in bed at night and visualize my way round it – every corner, every bump, every straight, lap after lap after lap. Sometimes I’d wake up and think, ‘Shit, I only got to Ballacraine last night. That’s no good.’ Some people count sheep when they can’t sleep but I used to do as many laps of that damned course as I could before sleep took over.

Anyway, after I’d pulled out of the Junior class race I doubted whether I’d be able to ride in the Senior event with the same dodgy frame. Luckily, I met up with Ray Cowles who had offered my brother a ride on his 500cc bike before he was killed. Ray was fielding Ian Lougher at the Manx but he crashed in practice and broke his collarbone, so Ray offered me the use of his TZ350 Yamaha for the Senior. I finished fifth in the race up against much bigger and faster 500cc machines which was pretty good going and I think I was the first 350 bike home, lapping at around 107mph.

I may have become the first man in history to lap the TT at over 120mph in 1989, but back in 1984, lapping at 107mph felt awesome. If someone had told me then how fast I’d eventually end up going round that track I’d never have believed it. The 350 lap record at the TT proper was only about 112mph, so I wasn’t far off the pace of the professional riders and that’s when someone suggested I enter the TT and get some money back for my efforts instead of doing the Manx again. The Manx was, and is, an amateur event but the TT paid start money to riders so at least some of my expenses would be covered, and if I managed to win some prize money then so much the better.

I certainly needed the money because I was broke when I got back from the Isle of Man. So broke, in fact, that I had to sell my Yamaha RD250LC road bike. That left me with no transport at all, but Jim Oliver once again came to the rescue and gave me a Honda C70 step-through scooter just like the ones you see grannies riding to the supermarket on. All that was missing was a little basket to put the cat food and tins of corned beef in.

The bike was an MOT failure so it was worth practically nothing but I was grateful to Jim all the same. Everybody laughed at me on that thing but I rode it every day regardlessly for two years. There I was, Steve Hislop, second in the Manx Grand Prix and just six months away from becoming a TT rider and my only road bike was a daft, old granny’s scooter. I even remember going to work a few times in my papa’s Reliant Robin three-wheeler for want of anything better! But I eventually had the last laugh as I started a trend for riding scooters in the area. A few of my mates got strapped for cash too so they all took my lead, sold their cars and bought scooters. From feeling like an idiot riding one on my own, it actually became a brilliant laugh with all of us riding round together on them.

Looking back now I really should have spent that winter looking for sponsorship, but I was never any good at that. I was very backward at coming forward and I could probably have sold myself a lot better if I’d been a more cocky type. I did write letters to local firms, asking if they’d be interested in helping me out, but I realize now I didn’t push hard enough. I hated the thought of going begging for money.

One person who did help me a lot, though, was a guy called Brian Reid who used to drink in my mum’s pub. He helped out writing letters and with other things, and I used to take him to the races sometimes. He became one of my biggest supporters and even helped start a Steve Hislop supporter’s club to try to raise some money for racing. One night, as he was playing pool in the pub, Brian stumbled backwards quite dramatically and we all thought he was pissed so we just laughed about it. However, it turned out to be the first signs of a rare disease of the central nervous system and he’s now in a wheelchair for life. But eventually he got the coolest wheelchair around when it was sprayed up as a replica of my famous ‘Hizzy’ helmet in shocking pink and blue!

Brian’s a great bloke and has such a passion for bike racing. He wrote to all sorts of people such as Paul McCartney and Richard Branson asking for sponsorship and eventually he landed me my first proper sponsor – Marshall Lauder Knitwear of Hawick. Not quite Richard Branson, but it was a start and I was grateful for it.

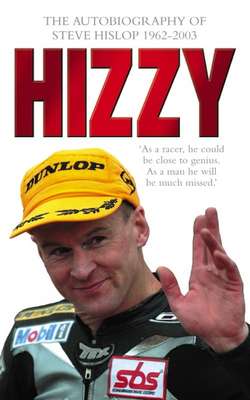

Brian was also responsible for the ‘Flying Haggis’ logo on my helmet. I’d been nicknamed that by commentators and Brian thought it would be a good idea to play on it to get myself noticed a bit. He took my helmet up to the day-care centre he attended and one of the art teachers painted the haggis with wings, and I’ve kept a variation of that design to this day.

Prior to my first TT in 1985, my employer, Jim Oliver, asked me what bikes I had to ride. I told him I only had the Yamaha TZ350 and to race that in the Senior class against 500cc machines was going to be an uphill struggle. When you make the effort to go over to the Isle of Man it makes sense to enter as many races as possible to make it worthwhile and increase your chances of winning some prize money; if you’ve only got one bike and it breaks down, it’s all over. Jim knew this so he pointed to a Yamaha RD500 in his showroom and said, ‘Take that for the Production race and enter the Formula One on it as well while you’re at it.’ Result. It was only a standard road bike but at least it would be good enough for the Production race. I ran that bike in on the roads of the Scottish Borders with Wendy Oliver on the back most of the time and no matter how fast I went, she prodded me to go faster. She was totally mad. As usual, I had my one meeting before the Island trip to make sure my 350 Yamaha was going okay. It was a miserable, sleety, wet day at East Fortune in East Lothian and I bagged a couple of second places, but my heart’s never been in racing when conditions are like that and it still isn’t. Despite what a lot of people think, I can actually ride in the wet but I just don’t like it. After all, I did keep up with Mick Doohan for a whole session in the pissing rain at Suzuka in 1991 and there’s no one faster than him.

Apart from my rides in the F1, Production and Senior races, Ray Cowles also gave me a bike for the Lightweight race so that gave me a ride in almost every race but the sidecars!

At least my crossing to the Isle of Man went smoothly again, which couldn’t be said for Joey and Robert Dunlop that year. They took their customary means of travel, which was a fishing boat and the bloody thing sank! Joey’s Hondas were being transported on a ‘proper’ boat, but Brian Reid and some of the other Irish boys watched helplessly as their bikes sank to the bottom of the Irish Sea. Everyone escaped unhurt and the bikes were all recovered but had to be stripped and soaked in diesel to stop the salt water corroding them.

Many people would be psychologically scarred after an event like that but Joey just jumped on a plane, headed for the Isle of Man and became only the second man in history to win three TTs in a week. The next man to achieve that honour would be me, but that was still a few years off. Just for the record, the late, great Mike Hailwood was the first to win a treble back in 1967.

Considering that 1985 was my first attempt at the TT and I didn’t have the best of machinery it wasn’t a bad week for me. I finished twenty-first in the Formula One race and tenth in the Production 750 (I was the first 500 home and managed a lap at about 108mph). I pulled out of the Lightweight class when Ray Cowles’s bike broke down and then I finished eighteenth in the Senior class on my little 350 Yamaha.

Most people agree that you’ve got to go to the TT for three years to learn it properly before you can start thinking about winning races and that’s exactly the way it worked out for me. So although those finishes may not look fantastic on paper, they represented a steady learning curve and, anyway, simply finishing a TT race is an achievement in itself. Jim Oliver was especially pleased because the Yamaha RD500 he loaned me got sold straight after the TT – it had been sitting in his showroom for months beforehand because he just couldn’t get rid of it!

I came back from the Island quite full of myself because I felt I had done really well. I hadn’t gone that much faster than I did at the Manx, but I had a lot more experience under my belt and knew I was going in the right direction. I was used to coming back from the Island in September when the Manx was finished and that was always pretty much the end of the racing season. But this time it was still only June when I got back home to Scotland and I really wanted to go racing again. That was the first time it had ever dawned on me that there was more to bike racing than just two weeks on the Isle of Man each year. It sounds stupid but I had never really considered going short-circuit racing properly – it just never entered my mind.

There was a meeting at East Fortune a few weeks later so I entered that and got a third place in one of the races. That’s when a guy called Frank Kerr came up to me and asked what I was doing in September. I said I had no plans so he asked if I wanted to ride for Scotland in the annual Celtic Match Races, as he was the Scottish team’s manager. It wasn’t a big thing really but there were teams from Scotland, Ireland, Wales and the Isle of Man and I thought it sounded like a bit of fun so I agreed to take part. When I asked him where it was he told me it was at Pembrey. I thought, ‘Where the fuck’s that then?’ Pembrey? I had never heard of it. It turned out to be in Wales.

There were races on the Saturday and the Sunday, and in both the 250 and 350 events I finished second to Irish rider Mark Farmer with whom I immediately became friends but who, like too many bike racers, was to lose his life at a young age. Mark’s death at the 1994 TT was extra sad for me because I was the last man to see him alive. I passed him in practice between Doran’s Bend and Laurel Bank when I was on the Honda RC45 and he was on the experimental New Zealand-built Britten machine. Because we were good mates, I looked back at him as I passed and gave him the fingers but then a couple of corners later at the Black Dubhe crashed and was killed. Mark had been a great friend of mine since I met him back in 1985 and his death was a great loss to bike racing.

I also got a second, third and fourth in the open class at the Match races to make me the highest points scorer in the Scottish team and we won the competition overall, too. It was a brilliant weekend both in terms of racing and in meeting new people and getting pissed up. That’s when I realized what I had been missing all that time, so I decided there and then that somehow, I was going to get the money together to race a full season in 1986.

I finally realized too, that all those years of getting drunk and crashing cars had been totally wasted. I had been a good-for-nothing waste of space but now that I had decided to go racing full time I was determined to make up for it. Now I had a purpose in life – a reason for not going out boozing, a reason for working late, a reason to live, and that actually made me feel extremely good.

So from that point on, the piss-artist bum was gone and he was replaced with a focused and dedicated motorcycle racer. Bike racing may be a dangerous sport but, ironically, the sport which took my brother’s life actually gave me a life and plucked me out of obscurity.

Obscurity doesn’t pay much, as I was finding to my cost. My job as a mechanic never paid well and even when I left Jim Oliver’s in 1988 to become a professional racer with Honda I was only on about £90 a week which is shite really. It wasn’t Jim’s fault; it was just the going rate.

Fortunately, as I said before, my mate Brian Reid really came good for me in the winter of 1985 by finding me some sponsorship through a guy called Leon Marshall of Marshall Lauder Knitwear. It wasn’t the most obvious company to be associated with bike racing but I wasn’t complaining. Leon asked me what my plans were for the coming season and I told him I wanted to do the British championships. He wondered why I didn’t just do the Scottish championship but I never saw the point in that. I was living on the border anyway so I figured I might as well travel down to the big English races than waste my time riding in Scotland getting no recognition. I’m not knocking Scottish racing but I’d been there done that and was ready for a new challenge.

I had helped work on bikes for another racing mate, called Jimmy Shanks, at some of the Marlboro Clubman events in England in 1985 and thought I could run with that level of competition, so that’s another reason why I was keen to race in England.

I wanted to ride in the (now defunct) Formula Two class, both at British and world level, so Leon offered to pay for the engine and exhaust system which I needed to make my bike competitive. It cost £2600 and my first reaction was, ‘What? Say that again.’ I couldn’t believe anyone would do that for me and thought, ‘Whoopee!’ Leon also gave me £100 in cash for every race meeting, which was more than I was earning in a week so it was invaluable help and I couldn’t have done it without him. So my bike was painted up with ‘Marshall Lauder Knitwear’ on the side and I must have become the first bike racer in history to be sponsored by a knitwear company!

I didn’t get my F2 engine right at the start of the year. But I still had enough parts to run my TZ350 Yamaha in the ACU Star 350 championship rounds, and it was at the Snetterton round early in the season when I first met Carl Fogarty who went on to become four times World Superbike champion. We were watching practice from the pit like two Billy-no-mates, and he just strolled up and said, ‘All right, how’s it going?’ or something like that, and that was the start of our friendship. I don’t think Carl knew that many people in racing back then and I didn’t either so we just sort of latched onto each other. When they could, my mates Tosh, Cosh, Tommy and Linton would come along and lend a hand as would my girlfriend, Wendy, but they could never all make it at the same time due to work commitments so it was usually just one or two of them, if any. Otherwise I just went on my own.