Читать книгу Catheter, Come Home - Steve Rudd - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

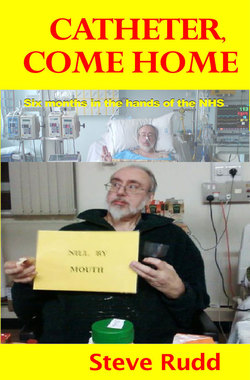

Оглавление1: Prologue

My name is Steve Rudd. I ate a dodgy stir-fry and almost ended up in a coma. Sadly, however, unlike Life on Mars, I didn’t get to travel back to 1973 and drive Sam Tyler’s Ford Capri through the stacks of cardboard cartons on the corners of the rainy, grimy, cobbled back streets of Manchester; nor did I get to meet Gene Hunt and fire up the Quattro. Not any Quattro. Not even Suzi Quattro. Still, from my own recollections of 1973, it wasn’t all it was cracked up to be, anyway.

What it did mean, however, was that I spent about five months (give or take a few dreary days) in the care of a major Northern NHS hospital, serving a combined population of many hundreds of thousands of people across the Pennines.

It had all started relatively innocuously. We were looking forward to our annual holiday on the Isle of Arran, and Debbie, my wife, had been busy getting the camper van loaded and ready. She was extra-busy as well, because she was job searching. She had decided that after 21 years being a residential social worker, enough really was enough.

In 2009, despite being very ill herself, she had managed to battle through her course and qualify as a teacher of adult literacy. Now, with the summer holidays approaching, she was looking forward to graduating “officially”, and after the holidays she was going to come back and put in her official resignation straight away, thus ending her “day job” after 21 years as a residential social worker, while simultaneously applying for any and every teaching job going, before the start of the new term.

So, change was in the air, as she spent time packing stuff into the camper van, ready for the off, and I, too, was counting down the days until we could load Tiggy on board, settle her down on her special little dog-bed in the back, leave Kitty once more in the tender care of Granny, and set off on our annual trundle up the M6, leading eventually to the ferry port at Ardrossan, to embark for Arran.

We’d planned to go on July 19th 2010. As good a day as any, we thought. On July 8th, Debbie was doing one of her final overnight sleep-in shifts at Beech, leaving me on my own for the night. So I did what any self-respecting, self-catering husband would do, I decided to use up some leftovers. Leftover rice, from the day before, what’s not to like? Add a can of stir-fry vegetables. Some soy sauce, and turn the heat up. Sorted.

I must admit, I had misgivings even when I was eating the stuff. Mainly, though, because I hadn’t heated it through enough, and it was a bit cold. I toyed with the idea of putting it back on the gas, but I knew I was going to be busy later, so I pressed on regardless, and had it lukewarm. I offered my leavings to the dog. She declined. Sensible dog.

The pains started shortly afterwards, shooting pains in my stomach, to be precise. For over an hour, I was completely immobilised by it, just sitting there clutching my stomach, until it eventually subsided a bit. I had no doubt that, somehow, I had given myself food poisoning or something. I managed to phone Debbie on her mobile and let her know I was feeling grim and going to bed, all thoughts of any further work abandoned for the night.

Somehow, I dragged myself upstairs and got into bed, complete with hot water bottle clutched against my stomach. Eventually, I fell into a fetid, foetal, fevered sleep.

The next day, I actually felt slightly better. I wouldn’t say I was back to normal, but there was an important meeting at my day job about a potential new distribution contract being scheduled so I did make an effort, braced myself with a strong cup of coffee, and made the journey to the office. I wasn’t at my best, all day. In fact, on reflection, now, I can see that I hadn’t been at my best for some days, weeks or even months. I managed the meeting competently enough, but soon afterwards I started feeling ropey again, and left work early.

When I got back on that Friday night, I went straight to bed, something which I rarely, if ever do. I didn’t need the hot water bottle this time around, but I did still feel grim, grey and grotty. Saturday morning came and went, unbeknown to me. Eventually, about lunchtime, I surfaced. I didn’t feel at all good. In fact, in the armchair downstairs by the fire, I quickly fell back to sleep again. Both Debbie and I realised I wasn’t doing anybody any favours by just lying around like a drugged-up walrus, so I dragged myself back upstairs again, and went back to bed.

And stayed there all Sunday, and some of Monday morning. Having decided that I was feeling too ill to try and drive, I phoned the local surgery. No, there were no home visits, but if I could get to the surgery, I could see the Emergency Doctor. Whoever he was. I decided to attempt it.

I got as far as the bathroom before I fell. Once on the floor, I found I couldn’t lever myself up, nor could Debbie, a) because I weigh much more than her and b) she wasn’t supposed to be exerting herself anyway. By a process of sitting up and shuffling on my bottom, I managed to get down the stairs and onto the settee next to the fire. It was pretty clear that I wouldn’t be attending at the surgery, so we rang them back. No, there was nobody available to come out and see me. They suggested if it was really bad, calling an ambulance.

I stayed on the sofa for the remainder of Monday, Monday night, all Tuesday, Tuesday night, all Wednesday, and Wednesday night. It wasn’t as much of a trial as you might think, since I wasn’t eating or drinking anything. I just passed the time dozing in a sort of pain-haze. I had several attempts to get up, but couldn’t summon the strength. On the Tuesday, I had rung the surgery as soon as the appointment line opened, trying to get a home visit. Nothing doing. In fact, on Tuesday, all of the appointments at the surgery itself had already gone by the time I climbed from number 47 in the queue to actually speaking to a human being. So that was Tuesday. On Wednesday, the same again – but this time the surgery did offer to send a squad of district nurses round to take my temperature. Or I could call an ambulance. I persisted, and finally managed to speak to “the Emergency Doctor” by phone, describing my symptoms to him as best I could. He prescribed me some anti-biotics - I can’t remember the name but it began with “Endo” – oh, hang on, it was Erithromythrin - over the phone, sight unseen. Desperate for any remedy by this stage, I despatched Debbie to the surgery for the prescription, she returned with the drugs, and I popped some straight away. No discernible effect.

Finally, on the Thursday, I had to deploy my secret weapon on the surgery. A phone call from my little sister. Sis was in fact a “sister” in more ways than one. She ended up as a ward sister at Leicester Royal Infirmary after twenty years of various nursing. Nowadays, she is in charge of a squad of district nurses in Northamptonshire. Not a lady to mess with. After she had called the surgery and used a few choice medical phrases, probably including all the ones she learnt when she dropped a full bedpan on her foot as a student, the Emergency Doctor phoned me back. Would this afternoon be convenient? I replied that, in my present state, there was no need to consult a diary, I wasn’t going anywhere.

At about a quarter to two, he turned up, and was ushered into my presence by Debbie. Tiggy, on her own sofa, in the warm, sunny conservatory, raised a quizzical eyebrow in his direction, determined that he was an unlikely source of either treats or threats, and promptly went back to sleep. He, meanwhile, took one look at me, at my general demeanour, and at my distended abdomen, and dialled 999 on his mobile for an ambulance. And that was him, gone.

The ambulance came not long after. Two burly ambulancemen hauled me upright, the first time I had stood up on my feet for three days, and frogmarched me out to the lobby. Once they had got me through the narrow part near the kitchen door, they sat me firmly in one of their little wheelchairs. Then they wheeled me out, along the drive, winched me up into the back of the ambulance, transferring me on to a trolley. Debbie handed them a bag of things she had hastily thrown together for me, the doors closed on her, the blue light came on, and we set off in a cloud of dust. And that was me, gone.