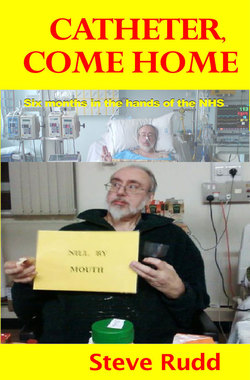

Читать книгу Catheter, Come Home - Steve Rudd - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление2: Admission

The first ward I was admitted to was a general assessment unit at Huddersfield Royal Infirmary, which is where I guess all the waifs, strays and neer do wells get dumped – at least until someone with a smattering of medical knowledge can decide whether they are dead or not, and if not, how much of the NHS’s resources it is worth expending on them, and at what likely reward.

It was teatime when I was first admitted, and predictably, the first steps were to document that I was indeed Steven James Rudd, dob 06/04/1955, that I was not diabetic, allergic to anything, or on any long term medication. They also rigged up a drip and started pumping clear fluid of some sort into my arm. I wasn’t fazed by this, I mean, come on, I have seen Holby! I may even have used the word “intubated” in my incoherent ramblings in a vain attempt to impress them. Soon I had added “Patient 461169” to my impressive list of titles and decorations I’ve collected in my life, which had hitherto been a very short list, but at least for this one, unlike, say, my university degree, I got to wear a tangible manifestation of it, for all to see, in the form of an indestructible laser label bearing the number, round my wrist. Still, it could have been worse, it might have been on a luggage-tag, tied to my big toe.

The first slightly strange departure from what passed for normal came when one of the doctors, young, female, blonde, pleasantly pneumatic, utterly charming, came to my bedside and said that they had been having a word about me, and they thought I would benefit during my stay with them by having a catheter fitted, to drain the urine from my bladder as I produced it, thus saving me the trouble of having to pee. It seemed to me to be an admirable idea, so I assured her I had no objection.

Unfortunately for me, it turned out not to be the luscious Dr Pneumatic that fitted it, thereby denying her the sight of my todger in all its glory, but a rather callow, nervous youth who appeared to be about 14, and whose only intelligible mumbled sentence, as he first snapped on the rubber gloves and then introduced the thin plastic tube on its rather improbable journey, inexplicably contained the word “balloon”.

Anyway, suitably fitted, there it was. I looked at the clear plastic tube leading from it over the edge of the bed and in no time at all, I had invented “Catheter Scalextric”, whereby you try and hurry the pee around all the curves and into the bag. Other than that, it looked just like the tubing used in home winemaking, and I was glad that I had never made white wine at home, only red, or I may have been put off the enterprise altogether in future.

There was some talk amongst the knot of miscellaneous medics who kept glancing over and muttering about me, that I might be transferred on to a more general, surgical ward, which left me in a rather anxious fame of mind, but I was also told that, given how late in the day it now was, I was unlikely to be moved that night. Relieved, I settled down to sleep, awaking suddenly at about midnight, when one of the porters dinged the tip of my catheter against a door jamb, as I was being moved into my new ward. Welcome to the Hotel California. Too tired to care by now, I cursed the throbbing, and went back to sleep.

My first impression of the new ward, next morning, was not a good one. Two beds along from mine was a guy who had just woken up with a massive pain in his head, a fact he was stressing to the nursing staff over and over again in no uncertain terms, very loudly, with added expletives for emphasis. This triggered a full-scale, draw-the-curtains emergency, with people piling in left, right and centre, to try and stabilise him, I guessed. Eventually, they wheeled away his bed, with him on it, still plumbed into to tubes and monitors, out of the general ward and into a side room where they could, presumably, work on him, but he died there, an hour later. According to others on the ward, he was a former engineer, aged only 61, and he’d been sitting up and chatting with them all the night before, as good as gold.

Having taken time out to reflect on that sobering experience, I realised that the ward was starting to take on an even-busier aspect. At the same time, though, everything gravitates to the same level, and everyone tacitly joins in the “Mustn’t Grumble” Dunkirk-Spirit type humour, false bonhomie and general “thumbs up” cheerfulness, where a smile can sometimes almost be a grimace, that we British adopt in socially uncertain situations, and that’s supposed to get us through. After a while, though, even this palled, and began to irritate me as much as fingernails down a blackboard.

I was also struck by the presence of some extraordinary patients, whose sole raison d’etre seemed to be to wander round and cause chaos. One such was Marnie, an elderly lady who was much given to rambling around (in both senses of the word “rambling”) the “Male” ward dressed in her nightie, asking people what they were doing. When apprehended by the nurses and pointed back to her own bed, she invariably turned nasty, telling them in no uncertain terms how she didn’t like them, and they could go away, in a manner involving concepts of sex and geography(!) She would not have been out of place in 18th-century Bedlam or Newgate, and she repeated the same performance at regular intervals all day, and every day I was on that ward. A finer candidate for a tranquilising dart in the neck, I never did see.

The whole ward was full of extraordinary characters, though, many of whom seemed to just wander around at will, including a bloke who pushed a large upright cart full of the morning’s newspapers, magazines, sweets, and bottles of coca cola etc., which he sold to the patients. So you could be assessed for obesity, then celebrate afterwards by buying a toffee crisp, a mars bar, and a tube of pringles. Suddenly, through the throng, came the coffee trolley with one squeaky wheel. I assume that, somewhere in the original Beveridge Report, there is a clause stating that all hospitals must possess at least one coffee trolley with at least one squeaky wheel. This one was ours.

By far the most bizarre character, however, was the soup man, who came wandering up and down asking who wanted soup. He was actually a member of the catering staff, not just some random member of the public with an interest in soup, but even so… What was perhaps oddest about him was that his answer to the perfectly reasonable question “what flavour is it?” was that he didn’t know. I hadn’t realised, before I was admitted to hospital, the crucial importance of soup to the NHS. It is not too much to say that it has almost a semi-religious significance, so much so that it occupies its own, peculiar, semi-detached status from the rest of the meal provision, at least at HRI. But the most amazing and miraculous thing about NHS soup seems to be that – a bit like the Higgs Bozon – nobody can tell you what it is until after it has been created!

I think that deep down in the hospital kitchen, they must have something like the CERN large hadron collider, and at the appointed hour, the hospital’s Soup-Priest dons the ceremonial tabard, picks up the sacred tureen, and descends the steps to summon the Soup-Gods. The lights probably then do something similar to “Who Wants To Be A Millionaire”, there is a blinding flash, and he turns and raises both arms to heaven, before proclaiming to the waiting throng “Leek and Potato!” (Is that with croutons, or leptons?)

My soup-related reverie was distracted by Jim, on the bed diagonally opposite. He (lucky chap) was getting ready to go home that day, and he very kindly offered me the remains of his bags of boiled sweets. Which, apparently, someone had originally passed on to him. It felt like handing on a baton, and we fell to talking about how your horizons got shortened in hospital. He had a fairly high-powered job in the real world, and we got talking about “To Do” lists. I revealed that since coming in to hospital, mine had shrunk to “Have X Ray, Move Beds if possible, Do Poo” and I had only managed two of them so far. Eventually, Jim departed, leaving me as the guardian of the sweets, and I wished him well. Then I returned to watching the endless stream of people still parading past me, through the ward.

By now, I was getting used to the speed at which things move in the NHS, which has its own time-space continuum, completely different to the rest of the universe. As an example, “five minutes” to a nurse, can be an elastic amount of actual time, anything from twenty seconds to an hour, depending how busy she is at the time, and how many unforeseen extra demands on her time crop up while the “five minutes” elapse. It is best, I found, to cultivate the virtue of patience. To be a patient, perhaps, or at least to be a little patient, as in the old “doctor doctor, I keep on getting smaller” joke. Old jokes were preoccupying me that day, for some reason. The presence of the drip putting liquid into my arm, and the catheter taking liquid out of my bladder, brought to mind the old joke from Catch-22, where Yossarian looks at the casualty in the medical bay, festooned with tubes, and suggests just tying them all together “to cut out the middleman.”

I spent my second night in hospital lying awake (I found, for the whole time I was admitted, that it is impossible to sleep at night in a hospital, don’t ask me why, it’s something to do with the people wandering about, muttering crazily and farting in their sleep, and that’s just the medical staff, especially the night duty nurses, who carry on their 3AM conversations at daytime pub noise levels, oblivious of people trying to get some kip).

I was listening to the changing tone of the thrumming of the central heating or something, some huge engine or dynamo deep down in the bowels of the cellars. It reminded me of trying to sleep in a Pullman seat on the night ferry from Holyhead to Dublin, and listening to the engines changing note in the middle of the night as the captain changed course to avoid the Isle of Man. With occasional input from passing drunks (I mean on the ferry, not in the hospital, but you get the idea).

Saturday dawned with the knowledge that I was to have an Ultrasound Scan that day. By now I had become accustomed to giving my date of birth – you are asked for it so often, in hospital, in fact, that I eventually took to automatically adding it to the end of my name, along with my patient number, as if I had been in the army. I may even legally adopt it, together with “vegetarian” and “not allergic”, as part of my full legal title. They wheeled me up to the X-Ray ward in my bed, and spent a considerable time smearing gel on my distended belly. They then took pictures of my insides. Simple as that. I even looked a bit pregnant. Perhaps I should have asked for one of those little printouts, like pregnant mothers carry round, to show people – “yes, and this is my spleen, ooh look, it’s waving its pyloric sphincter in that one. Yes, the radiographer said I had a cute distended abdomen, or something…”

The remainder of the weekend passed without any discernible incident. I was returned to my bed, and began to get a flavour of the way the NHS machinery goes into “slow” mode at weekends, with vast acres of time populated only by tumbleweed and passing people busy about some unknown purpose.

I had also begun to notice the daily routine of the place for the first time. Wake the people up, bath them, feed them, change the bedding, lunch, visiting, tea, visiting, evening food, then go to bed. All of which is one humungous logistics operation, that never stops, interspersed with the actual medicine and healing stuff going on, in unpredictable skeins that could lead anywhere.

I also noticed all of the different shades of the NHS uniform, and I realised that this was in recognition of the different parts they played in the endless logistics treadmill. The differing depths of the blues in the nurses’ uniforms denote seniority and experience as well, but there are also white tunics trimmed with red for blood staff (or “Flea-bottomists”, as I came to call them) white tunics trimmed with black for physios, light blue for student nurses, pale pink for the people in charge of food orders, except that “Soup” contingent seems to have its own “red” brigade – it would do, of course, soup being so apparently crucial to our well-being.

Then there are the green-clad cleaning company. I mean “company” in the Medieval, rather than the corporate sense, and this connection in my mind was what finally unlocked the key to what it was I was actually watching - It became obvious to me in that instant. The whole place was actually a monastery or “infirmary”, in the original medieval “Hospitalling” sense of the word. Still being run to fixed hours, with all sorts of differing pilgrims, visitors and inmates, and staff with defined duties.

Some of these, the kitchens and the cleaners of course, could even have been the same as in Medieval times, but in this modern monastery, we have subsumed religion and the liturgical aspects of monastic life to the lore of the doctors.

The principle, though, is still medieval charity, stretching back to the days when the local Lord would lay aside the wherewithal to treat “Twelve Lepers of Duxenforde” or some such phrase, and around that germ of a donation would grow up monastic buildings, farms, estate offices, the whole establishment. But the fact remained, and with dawning awareness I realised that I had fallen into a 21st century re-creation of the monastic ideal of charity to the sick.

A concept that went back to the time, ultimately, of the Christian ideal of the Good Samaritan and was based eventually on loving your brother as much as yourself. True, I was ill, and not loving every minute, but it was still majorly interesting, and I liked to think Beveridge would have seen the point, although the people who created the NHS were probably more interested in life before death. With soup.

And of course, like the Monasteries, the NHS hospitals are now living under the threat of Dissolution. The new Tory/LibDem administration is pledged to make massive cuts in the public services, although they have said they will “ring fence” spending on the NHS. Presumably, though that only means sticking to previously-planned expenditure, not increasing it in any way.

But it also turns out, now, at the time of writing, some18 months after the events which first prompted these thoughts, to include breaking up the NHS, turning it upside down, and putting it through a needless and costly reorganisation, though strangely, no-one you ask in the street can ever remember voting for this!

Having concluded my monastic analogy, I noticed a nurse, about to leave the ward, stop and reach out with her hand to get a toot of the general antiseptic, anti-viral gel, from a plastic dispenser on the wall, in just the same way as an earlier acolyte may have dipped her hand into a piscina for Holy Water on entering or leaving.

Later that day, nature (and some sort of laxative) having inevitably taken its course, I was introduced to the joys of the bedpan, the sort that looks like the wedge-shaped plastic dustpan of a dustpan-and-brush set. It was to be the first of many. I am pleased to say I managed to acquit myself, and not, as I had feared, to shit myself. Not that time, anyway.

By the Monday lunchtime it was clear I was not going home, or anywhere near it, any time soon. The consultant who was supposedly looking after me, for a start, did not do ward rounds on a Monday, so all I was able to find out about my condition anyway was that there was no abnormality showing on my ultrasound scan. Which of course turned out to be wrong, later. The “bloods”, which I discovered is what medical people call blood tests, had a high white blood count, so the consultant was going to take additional precautionary tests – now there was a mention of a Cat Scan on Monday. All of this was vouchsafed to me by a beautiful, slim young girl with perfectly almond-shaped light brown eyes. I couldn’t say for definite, but I assumed she was yet another doctor. The place was crawling with them. Plus, I noticed, they almost always went around in gangs, particularly when they did ward rounds. Perhaps they were scared of being mugged by the nurses.

I passed the time by watching the green-clad cleaners, who by now I had dubbed “The Worshipful Company of Swiffers”, all parading through the wards like the Pope’s Swiss Guard, implements at the ready. They split up, taking on different tasks, and their brushes and mops seemed to have been specifically designed for a single job - one young girl had an extending duster-type thing on a right-angle pole with which she carefully polished all the tops of the rails that held the curtains round everyone’s beds, and I found myself wondering if this was something she’d bodged up for the purpose, or whether there was actually a factory somewhere that made these extending dusters just for this singular purpose.

By now, I was having daily blood tests; also my blood pressure was being taken twice a day, I had had urine tests, a chest x-ray, a stomach x-ray, and so on. On Monday I discussed results with the House Doctor who had said there was nothing averse about my ultrasound and they took additional blood samples for culturing. I got used to people asking questions like “do you have a cultured stool?” (No, all ours came from IKEA) and “Are you catheterised?” (Who made me? God made me). The blood tests became so routine I could answer the questions about my name, date of birth and hospital number with all the nonchalance of a Prisoner of War in a black and white 1950s film about Colditz. I was always rewarded by the words “sharp scratch”, which is what the Fleabottomist invariably says as she sticks the needle in your arm.

Hospital is a strangely sexless place, despite what every hospital soap opera from Dr Kildare onwards would have you believe. During my entire stay in hospital, the number of nubile young women who had said to me “Mr Rudd, your penis is very swollen and inflamed”, and then gone on to examine it tenderly, while wearing thin latex gloves, will never be surpassed in my life. Sadly, however, every last one of them was acting in a purely professional capacity. The number of strangers’ hands to have touched my bottom is even greater. In fact, during my stay in hospital, I had things done to my nether regions which I had never even considered, in my sheltered life beforehand. And mostly by people who were being paid £7.64 an hour. I am not sure I would even touch my own bottom for £7.64 an hour.

There should be a statue in Whitehall of “The Unknown Hospital Worker” paid for and maintained out of an annual tax on drug company profits, and we should all make a pilgrimage there once a year, to lay flowers and to say thanks to the NHS.

I should have mentioned visitors, of course, both my own, and others. My visitors were a select, small band, at least at first. My sister and my brother-in-law hard-arsed their way up the motorway from Northampton on two successive weekends, Debbie came every day, sometimes bringing her Mum, and in the course of my stay I was also visited by Phil, who used to work for me, Debbie’s Dad, Owen my old schoolfriend and his wife Susie, who called in en route from Wales to Liverpool (as you do) three or four people from my office, and several people from the BBC Archers web site, of whom more later.

What surprised me, though, was the people who didn’t come. Strangely, it didn’t occur to me at the time, but afterwards it hurt. I won’t list them out here, they know who they are. Anyway, it’s all blood under the bridge now, but there’s nothing like a six month stay in hospital to bring home to you who your friends are.

Other people’s visitors were also interesting, as an inveterate earwigger on conversations, I sometimes had to bite my tongue to resist the urge to join in. One visitor I really missed seeing was Tiggy. Not only had the poor mutt been deprived of her holiday and her annual dip in the bracing waters of Kilbrannan Sound, but she must be wondering what had happened to Daddy. I suggested as much to Debbie, who replied that as far as she was aware, Tiggy showed no signs whatsoever of pining for me, and the cat didn’t care if I lived or died as long as there was someone there to open a tin of cat food for her, but then that’s cats all over.

I did have a brilliant idea for a business opportunity while I was musing on the absence of my furry chums – someone should start manufacturing hygienic fur-fabric stuffed pets with realistic appearances and similar body weights to household pets, so you could feel the weight of the dog on the bed at night, just as if you were back home.

My sister told me that when she was nursing at Leicester, it had actually been mooted at a meeting that patients should be allowed to bring their real pets into hospital, given the therapeutic value of stroking an animal, which has apparently been shown to lower blood pressure. The idea got as far as the Head of Infection Control, who is alleged to have heard about it and immediately roared,

“Pets?! F***ing PETS?!!”

in a voice that rattled the windows, and no more was said. So, who knows, perhaps my idea has legs – or not, as the case may be.

Anyway, by the end of the week, it had become clear that a) I wasn’t getting better and b) the surgeon was coming to see me, apparently. Which he duly did, accompanied by the usual entourage. He explained calmly that I was seriously ill. My bowel was perforated, and I had peritonitis. They were going to perform an operation called a bowel resection, which basically involves chopping out the bit with the hole in it, and then sew the two ends together, a bit like repairing a hosepipe, I guess. And when was I supposed to have this operation? Now, this afternoon, today, he said. Ah. Right.

While all that was sinking in, I said it sounded very serious. He said it was. I said that I guessed it wouldn’t be a local anaesthetic, then. He said it wouldn’t. Ah, I said (already shitting myself mentally at the prospect - but not physically, that was sort of the problem) and tell me, Doctor, is there any alternative, what happens if I don’t have the operation? Then you will die, he says, and that was that. With a flutter of clipboards, they were gone.

All sorts of thoughts flitted through my mind, not least of which being, right, this is it, Steve, you’re 55, it’s been a good run, but the Grim Reaper’s got his megaphone in his hand and he’s saying ‘come in, number 55, your time is up.’ I supposed I ought to let Debbie know what was going on, and one of the nurses said they’d call her.

Then they got me ready for the operating theatre and put me into one of those backless gowns which I have never quite understood the rationale for, but I was hardly in a position to argue. Another nurse appeared, hovering by the bed, and explained that she was a Stoma Nurse, who had come to mark me up. I wasn’t really processing what she was saying, in fact, up til that point, I had survived 55 years thinking that Stoma was an island in The Hebrides, but it turned out that what she wanted to do was to draw on my body with a felt pen where the surgeon had to attach a poo bag if it turned out I needed one. She actually marked two positions on my distended, painful stomach, presumably annotating them with ‘cut here’ or some other helpful comment, I was past caring, feeling tears weren’t far away, wishing there was time to discuss things with Deb, wondering what she would do, or think, or say, about the prospect of me having to have a colostomy bag. Even the old joke about having the shoes to match didn’t cheer me up.

The simple fact is, dear reader, I was scared. I quite like being alive, for all its many faults and shortcomings, death is a much dodgier proposition, I mean it might turn out to be all sweetness and light and a world without pain, injustice, and Celine Dion records, but who knows? And I certainly didn’t feel ready to find out, that summer’s day, as I lay there in a really bleak place inside my head, thinking of everyone else outside enjoying themselves.

Eventually, the nurse who’d been on duty all morning came back, and said they were still having trouble finding Debbie, and it was time for me to go to theatre. Well, I thought, I always wanted to be on the stage, and the show must go on. I turned to her,

“I’m scared,” I said. “What if I die?”

“You’ll be alright,” she replied, matter-of-factly. “I’m coming up there with you, anyway.”

She was as good as her word, and stayed with me while the porters wheeled me down the ward, along more seemingly endless corridors, into a lift, up or down, I had no idea, out of the lift again, and into a sort of wide foyer area where a bloke in scrubs was waiting for me. He was the anaesthetist, it turned out, and he had loads of forms for me to sign, to say that if I died I wouldn’t come back and haunt them, and stuff like that. She wished me luck, and I was sad to see her go.

Then they wheeled me into a sort of antechamber, and he asked me, slightly irrelevantly, I thought, whether I minded if these girls (he indicated a group of student nurses behind him) watched me being put under. I said I had no objection, and I realised what it was about him that was odd, he sounded Australian. I was still pondering why anyone would swop Australia for Huddersfield when I realised he was fixing the mask over me and playing up to the gallery of appreciative girls behind him (well, he was Australian) doing all the classic anaesthetist things of saying ‘count backwards from ten’ and shit like that, and then the darkness closed over me.