Читать книгу Playing Lady Gaga, Being Nan Pau - Steve Tolbert - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

2

ОглавлениеMya sat on stacked bags of cement, dazed, trembling, her school uniform – green skirt, white blouse – dripping blood and rain into a watercolour on the floor. Hair, then soapy stubble, followed. That it was her hair and stubble barely penetrated her mind. ‘Sule Pagoda?’ she asked finally.

‘Below it, yes. As an abbot I have keys to its locked doors.’

She grew aware of his robe dripping, of a bitter taste in her mouth. ‘Is there water?’

The abbot flicked the razor to clear it of stubble and put it down. He passed Mya a bottle of water. She drank, passed it back, and he continued shaving.

‘Monks are prohibited from touching women, and still you carried me here and … touch my skull … cut off my hair, shave my head.’

‘Under the circumstances the sangha1 will understand.’

He finished, used a cloth to dab at shaving nicks, then started sweeping up.

‘Widows’ heads are shaved,’ Mya said, her own shaved head feeling as shrunken as the rest of her.

‘As a sign of having left family life behind, yes.’

She pictured political prisoners – her father even – sitting on stools under this sort of low light. Shouting voices demanding answers. Fists, boots and belts lashing out, their bodies soon aching, as hers would be after she was discovered and taken away.

Fast, hard footsteps came down the wooden stairs.

Mya’s eyes shot to the door.

A padlock scraped, clicked. The door burst open and in came a boy monk, his shoulder bag bulging. ‘Many police are on the streets,’ he said, acknowledging Mya with a nod before diverting his eyes to the abbot. ‘I got to Botataung District, though, and to the unit. No police were there.’ He stretched a hand Mya’s way. ‘But this girl’s mother was, and … she knew, she knew.’

The abbot mumbled something before leaning the broom against the wall and eyeing Mya.

‘I gave her your message and package,’ the boy monk continued. ‘Then I went to the monastery and nunnery. No police at those places, yet.’ From his shoulder bag he took out a mobile phone, a camera, a brown umbrella, two books, a wash cloth, a pink robe, an orange under-dress, a brown sash, a sling shoulder bag, a pair of sandals and a small roll of money, and placed them on a shelf next to Mya. He grabbed a bucket and took off again, closing and locking the door.

Once the staircase went quiet again, Mya reached up, touched her shorn head then moved a hand over the clothes. ‘So what happens now?’ she asked, though she’d worked out at least part of the answer: this was the garb of a novice nun.

The abbot sat on a stool. ‘You’ll need to stay here a while.’

‘And if I go home?’

‘You will be arrested.’

‘Along with my mother?’

‘Standard government policy: punish the womb that gave birth to the protestor. It’s not just the single person who can go to prison, but the person’s entire family.’ He kept his eyes on her. ‘Your mother is Karen,2 I believe.’

‘Partly.’

‘As you heard, she’s been contacted. She knows what’s happened, as everyone in Yangon must know by now. She knows you’re in hiding. She knows once your brother’s body has been identified it will be cremated, along with the others killed, and their relatives will be arrested. So she is leaving Yangon now in disguise and getting as far away as possible.’

‘How far away?’

‘If you know the answer to that and you are caught, resistance will be ripped out of you and you will tell the interrogators everything they want to know.’

‘I read once about a group in Sri Lanka called the Tamil Tigers. When they were at war against the government, each one of them wore an amulet around their neck containing cyanide tablets. When they were about to be captured, they swallowed the tablets. Every market in Yangon sells rat poison.’ Her eyes lingered on his. ‘So where do I go to find her?’

‘Have you been to Karen State?’

‘No, but I have an uncle there. And I’ve heard stories about it. I know that Karen people consider Karen State their homeland and that their bloodthirsty army are fighting the country’s military there. I’ve read about Karen cannibals, about Karen with horns growing out of their skulls, about Karen who kill just to cut off and bury their victims’ heads under bridges for good luck.’

‘Stories the government features in its newspapers, its agents spread in the market places, its generals tell their soldiers. But the Karen people are no more monsters than you or I. If you go into Karen State, yes, you’ll be amongst the government’s bitterest enemies. But you understand that already.’

Mya gazed at the floor, an ache gripping her throat. She took a deep breath, clenched her teeth and told herself if she did not move she would not cry. Her mouth tightened and she burst out in loud hiccupping sobs, like a three-year-old. ‘I start the day with my mother and I end up … here with no family at all; this storeroom, or a prison cell, or … or escape to a war zone my only options in life.’ She bent over, covered her face with her hands. ‘I hate Myanmar, its pig government, its police and soldiers who torture and kill people who want to make the country a better place. If I had a gun I’d go out on the street right now and willingly spend my next ten lives in the darkest pit of hell for the chance to shoot every policeman I saw. I’ve never felt so much hatred – and when I leave here, I’m supposed to be a nun?’

‘A novice nun.’

‘A novice nun then.’ She shook her head at the lunacy of the idea.

‘A novice nun who must learn quickly to control her emotions.’ The abbot paused, giving Mya time to settle down. ‘If MI discovers anyone mourning over the death of a protestor, that person will be arrested.’ He stood up to move the broom and dustpan to the corner then sat back down on the stool and watched her. ‘The fact is the protest march was recorded. Soon MI will be looking for you and everyone else involved in the violence, if they’re not already doing so. They’ll know your face. They’ll know your family. Disguised as a novice nun, you have some chance of getting into Karen State and joining your mother.’

‘Whereabouts in Karen State?’

He shook his head. ‘This is what I suggest. You travel to Karen State as your mother has. Trusted people will contact you. You’ll know who they are when they use the words, “Myanmar is beautiful this time of year. Don’t you think so?” Don’t open yourself up to anyone else. Memorise whatever information you’re given. Don’t write anything down. Be accepting. Be patient. You can no more hurry life than hurry the phases of the moon.’

He paused, a smile on his face, as if he were modelling it. ‘Try each day to smile. It is good medicine. Learn to avert your eyes, to make a mask of your face, to disappear into yourself. Feel yourself grow invisible in your stillness. Remember, as a novice nun you’re learning to live more in the spiritual world than the temporal one, so it is expected you’ll use words sparingly, or not at all, and that you’ll simply nod to acknowledge things said to you.’

He pinched his right ear. ‘And remember, walls have these.’ He pointed to his eyes. ‘And trees have these. So don’t linger next to them … Of course, there is a chance you’ll be caught. So getting there will depend on good fortune and how convincing you are as a novice nun.’

He pointed to one of the two books among the pile of clothes. ‘A condensed version of the Buddha’s teachings: the Tripitaka. Try to read some of it. It will help you. The money is from your mother and the monastery.’

‘You could be in great danger by helping me.’

‘The mere act of living and thinking differently in Myanmar can be dangerous. Fortunately our religion teaches us to deal with that.’

To show her gratitude, Mya said, ‘The old nun will serve as my model. Every minute I’m wearing that robe I’ll be carrying her image inside me.’

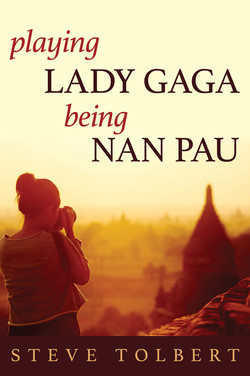

‘A younger version of that image, I hope, with hardier legs and better eyesight. Her nephew is a monk and a close friend of mine. Her name was Nan Pau and her karma was good … Yours can be too.’

‘Did I kill him – the policeman?’

‘And was that policeman killing the construction worker he was attacking before you intervened? It is how wars start. I doubt you did; but whether you did or not, the law is simple. There is only one crime – an act against the government. It covers all offences and punishment is the same, whether for speaking out freely or beating someone to death.’

‘Or hiding people who’ve done those things. I shouldn’t be here.’

‘You can leave whenever you want, but if you stay two or three days, the authorities will have completed their house-to-house searches. Their interrogation cells will be full. As well, you can prepare yourself by studying the Tripitaka. Waiting will also give me time to organise your escape and find you something more effective than rat poison should your escape end unexpectedly.’

Mya stared at him in disbelief.

He went on. ‘The first Sacred Truth – life is sorrow and suffering, true. But the suffering that comes from interrogation and torture goes beyond the teachings. And when Buddhist principles clash, compassion takes priority.’ He stood up. ‘So absorb who you are: a novice nun whose only desire in life is to worship and serve … and just quietly, to find her mother.’

Footsteps sounded on the staircase again. The door opened and the boy monk came in with a bucket of water. He set it down next to her and rushed out again.

The abbot picked up the camera from the stack of tiles, explaining, ‘Your new identity starts with a photo.’ He then handed Mya the robe, under-dress and sash, asking her to put them around her shoulders. When she had done so, he looked through the viewfinder and took her photo using the flash. ‘I’m leaving for a little while. While I’m gone you can clean up, put on your novice clothes and rest.’ He nodded towards a cot next to the nearest wall.

‘If something happens and I’m not back in an hour …’ He raised his eyes and pointed to a square on the ceiling that had been cut away and replaced with a panel of dark wood. ‘A prayer hall is above us. It has an elevated floor. You can hoist yourself up through the panel then follow the light and crawl out.’ He turned and left.

Mya washed and put on the novice clothes, then lay down on the cot. Nothing to do but mourn, feel numb, like her insides had been cut out. She picked up the Tripitaka and tried to read, but couldn’t. An hour, maybe more, before the sounds of scampering feet and thumping boots on the floor above startled her. Someone shouted, ‘OUTSIDE, OUTSIDE, NOW, NOW, NOW!’ There came a thud, like a bag of cement hitting the floor. Boots banged down the staircase. The padlock clattered; someone tried to wrench it off the latch. Then the boots went back up the stairs and moments later everything went still again.

She waited. Maybe a quarter of an hour passed without another sound before she climbed awkwardly onto the cement bags and lifted the panel high enough to peer out between the false ceiling and raised floor above, a rectangle of grey light to her right. She grabbed her things, shoved them in her shoulder bag and lifted herself up.

On her belly and forearms, Mya wriggled towards the light, emerging behind a large, glass-encased Buddha. She stood and peered around it. No one about, just the shrine-covered walls, and on the other side of the polished hall an altar laden with platters of hibiscus, jasmine and marigolds, smoking incense and dozens of flickering candles. Above the altar, a mammoth golden Buddha. On a cross beam above the Buddha, a swallows’ nest. Daytime still and Sule Pagoda was abandoned. Just something else she could never have imagined.

She walked out into the hall and sat in front of the Buddha, curling her legs behind her and gazing up at him. She explained how much she ached, how much she feared leaving Yangon. A thought came: maybe she could just hide in the storeroom, somehow arrange to have food brought in until … until when? She was eventually discovered?

The slap of flip-flops entered the hall. She jumped up, alarmed, about to run. ‘Police came and took the abbot away.’ The boy monk again, moving towards her. ‘I saw them from across the road.’

Mya recalled the abbott’s warning about what would happen on being caught by the authorities: ‘… resistance will be ripped out of you and you will tell the interrogators everything they want to know.’

The boy monk’s eyes were watery, his voice soft. ‘But there are no police now, so it is as safe as it will ever be for you to go.’

Her choice: either she got herself to the train station or walked out to the pagoda steps and sat and mourned until the police came and took her away.

The boy monk turned his back to Mya, bent over and lifted his robe. There came the sound of tape being ripped from flesh. He faced her again, a small, tattered book in his hand. ‘The abbot thought it would be better if I carried this, not him.’ He approached and handed Mya a guide book for English-speaking tourists.

She took it and the book sprung open to a page with an identity card fixed in the binding. She stared at the photo of herself – hairless, in a pink robe, brown sash over her left shoulder, and below her photo, a name – Nan Pau. She took out the ID card and flipped through the book’s pages filled with bus and train schedules, colourful photos and descriptions of famous places.

‘The night train to Moulmein leaves in two hours,’ the boy monk said.

Mya thanked him, knowing that in normal circumstances he wouldn’t have spoken to her, and her thoughts turned to the abbot. How long would he be able to hold out before telling his interrogators everything? ‘I must go now,’ Mya said, as much to herself as the boy. She dropped the book in her bag, left the hall and scampered down the steps, intent on getting to the train station as quickly as possible.

Outside the rain had stopped and the sun was beating down, drawing vapour from the wet pavement. Sule Pagoda Road was close to deserted, shops and stalls looking as abandoned as the pagoda. Only a few people on bicycles, an occasional motorbike taxi or car moving slowly up the road as if a truck-load of vipers lay tipped over up ahead.

The eerie quiet and lack of traffic weren’t all that surprised her. She thought she’d remain numb with grief, indifferent to being caught, and at first that was exactly how she felt. But as she walked, thoughts of her mother filled Mya’s mind. She needed Mya as much as Mya needed her. Mya’s feelings changed. She grew wary, conscious that Yangon was enemy territory now, that informers could be watching her from across the road, from windows and partially-hidden vehicles.

As she quickened her pace, her vigilance grew. She doubted she’d ever been more aware of herself, her surroundings and the exact distance between her and her destination. Alert to every movement and sound, she studied the road, footpath, cross streets, laneways and dead ends. And what struck her was how clean and tidy everything was: nothing at all to indicate a peaceful march for democracy, followed by a massacre, had ever taken place. Not a single blood stain or bullet casing; no bits of banner, flag or clothing – not even any plastic bag rubbish. It was like the entire area had been soaped down and swept clean by a massive broom, or most likely dozens of smaller ones.

She was approaching a boy and girl in school uniforms sitting on the low-walled border of a banyan tree, the boy eyeing its branches, his mouth pinched; the girl teary, slow to look away and keep her sorrow private. Mya recognised the girl from school, so lowered her eyes and faced the road as she passed them, half expecting her name to be called out at any moment. But the girl said nothing, and soon she and the boy rode past Mya on a bicycle, the girl side-on, head tilted into the boy’s back, her arms around his waist like he was all she had left in life. Mya watched them until they turned into a laneway and disappeared.

Remaining unrecognised boosted Mya’s confidence. Her determination strengthened; so too her anger. Images of her namesake – marble eyes, protruding bones – took over her thoughts. She recalled the nun’s words: ‘I should tell you, dear, I could not have got this far without your brother’s help.’ And just how far did Thant get you, old nun? Let me tell you: as far as the wall of police murderers who must have enjoyed their day. Think of the satisfaction they got. Like shooting birds out of trees. Using a hammer to crush a flea. And supposedly they’re Buddhists. Doesn’t that make you want to change your religion, old nun? It does me, even as I wear this robe to escape imprisonment. Buddhists arrested, beaten and killed by other supposed Buddhists. Myanmar’s in hell, old nun, and with the generals as our masters, it always will be.

She lost concentration and scolded herself, thinking: Nothing matters but getting out of Yangon, so get back to who you are – Nan Pau: positive, compassionate, self-disciplined; forever walking in the Buddha’s footsteps. And if she couldn’t be her, she might as well stop this farce right now and make up a banner saying something like, THE POLICE KILLED MY BROTHER. MAY THOSE RESPONSIBLE BECOME DOGS IN THEIR NEXT LIVES AND EAT CRAP. Then walk down the road with it, shouting and waving it in the air. How far? As far as her namesake got? Unlikely. A satisfying experience though; the rest of her pain-free life squeezed into a few minutes of revenge. And when the police came to arrest her, how long would it take for a bottle of rat poison to take effect? She looked down at her robe and shook her head. Had there ever been a more unlikely person to walk along this road in a novice’s robe?

Rat poison diverted her thoughts and caused her to revise her route. She needed to buy some before going to the train station.

On the next corner, a man in a red pin-striped longyi,3 white shirt and mirror sunglasses sat under a banyan tree. As Mya neared him, her heart beat harder, her stomach tightened. He might just as well have had his job description written across his chest, for although he wore different clothes now, Mya recognised him. She wanted to stop, to cross the road, to run.

Mister MI turned and saw her.

Mya lowered her eyes and passed him, her pulse in her throat. Seconds later hard-soled sandals, in time with her own, clapped the footpath behind her.

A trishaw driver pedalled past, his arms and shoulders shiny with sweat, his passenger seat empty. ‘Yes, please,’ Mya shouted, in a voice more resembling a market seller’s than a nun’s. ‘I want to go …’ The words ‘Chinese Market’ froze on her lips, the disinterested driver well down the road by the time she finished her sentence. She continued on, listening for those sandals but no longer hearing them. She slowed, stopped, looked around. Relief was instant. No one was behind her. On she went, past vacant vendor and fortune-teller stalls, the Sakura Tower and Trader Hotel, until she spotted the railroad overpass up ahead.

One more intersection: the massacre site, where policemen were stopping vehicles, checking ID cards and possessions, pulling people out and questioning them. Mya watched as two men were shoved into the back of a cage truck and driven away.

Fear nudged her back into the shade of a tamarind tree. Her eyes darted about. She recalled a shop that sold traps and poisons across the road and down a nearby side street. How to get there without crossing that intersection? She stepped out of the shade, turned and looked straight into the face of Mister MI, his mirror sunglasses boring into her. Only his lips moved. ‘You’re looking confused,’ he said. ‘Why? Does this road, that intersection, bring back recent memories for you?’

She, novice imposter, was about to be arrested. Her eyes found the footpath. Face hot, throat constricted, she tried to speak, but couldn’t. She forced a smile, gazed at cracks in the footpath and waited for what came next.

‘Your ID card.’

Mya took it out and handed it to him.

‘You’re trembling.’

It took all her concentration to reply, ‘A little. The city feels very tense.’

His eyes jumped from Mya to the card – once, twice. He returned it. ‘Have you come from the Sanchaung Nunnery?’

Stupid man. Where else would a novice nun walking in this area come from? Importantly, he didn’t grab her or appear to recognise her. She answered him in her quietest voice, ‘Yes, I have.’

‘A good distance away from there, aren’t you? Have you walked or taken transport?’

Mya looked out at the road, a sponge for so much blood just hours earlier. ‘I got transport,’ she lied, hating him. ‘I’m going to visit friends nearby.’ May you choke on a fish bone and die in agony. Holding her body very still, she forced another smile.

‘I trust they avoided the protest march here and are well.’

‘Very well, thank you.’ With every lying word she spoke, she sounded more and more pathetic to herself. In another life she’d have told him whose backside to crawl up. Though, like now, maybe only in her thoughts. ‘I want to buy a few things at the Chinese Market before going to my friends’ place.’

He studied her before flicking the back of his hand as if shooing her away. ‘Go then. You need only buy food for yourself for a day, maybe two, I should think.’

She had no idea what he meant by that.

‘Go on, off you go.’

Mya turned and crossed Sule Pagoda Road; she thought for the last time ever.