Читать книгу Predator - Steven Walker - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

1

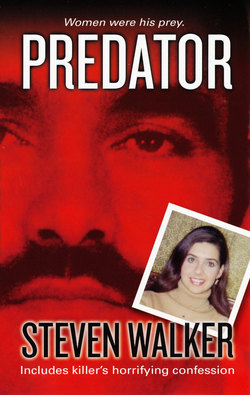

ОглавлениеDeborah Sheppard

August 2007

The rusting wheels of justice were given a shot of oil and slowly began to turn. A statement of probable cause and a motion for arrest warrant was signed August 28, 2007, by Michael L. Wepsiec, state’s attorney for Jackson County, Illinois. There were four counts of murder while committing forcible rape brought against the defendant in connection with the death of Deborah Sheppard.

The next day, the warrant of arrest commanded all peace officers of the state of Illinois to arrest Timothy Wayne Krajcir, and bring him without delay before the presiding judge of the First Judicial Circuit Court in the Jackson County Courthouse, in the city of Murphysboro. The amount of bail was already determined to be set at no less than $1 million.

Adrenaline was stirred. Lieutenant Paul Echols, of the Carbondale Police Department (CPD), couldn’t help but feel alive; to feel like he had made a difference and had a positive impact. He knew that he had played an integral part alongside the coordinated efforts of many others that finally helped to bring the case to a point where it might finally be solved. It was a cold case that had been pursued relentlessly for years without resolution. Echols was confident that Krajcir was guilty, but unless Krajcir confessed, his guilt or innocence would have to be determined by a judge or a jury based on the evidence.

Carbondale, Illinois, is smaller than Cape Girardeau, Missouri. Give or take a couple of thousand people, its population has hovered around the twenty-five thousand mark since 1970. There is one Muslim temple, one Jewish synagogue, two Catholic churches, and forty-seven Protestant churches located within the city limits. Carbondale is the epitome of the stereotypical White Anglo-Saxon Protestant (WASP) environment. Carbondale was selected as “Best Small City in Illinois” in 1990, and again in 1997. It was also awarded the Governor’s Hometown Award in 1991 and 1992. There is a central business district in the downtown area. There are several strip mall centers, and the University Mall is the single enclosed shopping area. There are two high schools and there is the nearby John A. Logan Community College in Cartersville. Carbondale is also home to Southern Illinois University (SIU), a comprehensive teaching and research institution with approximately sixty-one graduate programs and professional schools of law, medicine, and engineering. With about 6,800 employees, it is the area’s largest employer.

Being allotted the time to investigate cold cases, Lieutenant Echols had recently been responsible for helping to convict Daniel Woloson for the murder of Susan Schumake. She was a Southern Illinois University student who was murdered August 17, 1981. Her body was found along a trail, commonly referred to as the “Ho Chi Minh Trail,” which was frequented by students on their way back to the residence halls. The trail cuts across US 51 where the southernmost overpass walkway currently exists on the campus. Today the walkway contains a plaque that commemorates the current walkway in memory of Susan Schumake. As a communications major, Schumake was walking home at night from a WIDB radio station employee meeting in the Communications Building and was killed. Her roommates reported her missing that night, and her body was found two days later—apparently dragged about thirty yards off the trail.

Susan’s brother, John, described her as someone who was quiet in large groups or with people she didn’t know very well.

“If you knew her really well, she could be really funny and very engaging,” he said. “She was a very kindhearted person. I would say that one of the words that describe her best is peacemaker.”

John said that his sister enjoyed writing poetry and that she wanted to pursue a career in radio journalism. He had a lot of tapes of her preparing vocal spots for on-air journalistic reports.

About a month after Schumake’s body was discovered, Timothy Krajcir, who was deemed a sexually dangerous person and recently paroled, became a viable suspect in the homicide. Police investigators interviewed Krajcir but they had no solid evidence to connect him to the crime, and he denied having any involvement with Schumake.

Echols had just joined the force seven days before Schumake was murdered, and he did not become involved in the investigation. Now he had the opportunity to look into the case, which had remained unsolved for over twenty years. Before Woloson, the primary suspect in the case was John Paul Phillips, who was sentenced for the 1981 rape and murder of Joan Wetherall and was a suspect in the murders of at least two other women. While serving a forty-year sentence, Phillips died of a heart attack in 1993. He was posthumously eliminated as a suspect in the murder of Schumake in 2002 after his body was exhumed and a DNA sample taken from the marrow of his thighbone did not match preserved vaginal swabs taken from Schumake.

Echols began to look at the history of previous suspects and spent time attempting to procure DNA samples from them. Two previous suspects in the case voluntarily provided DNA samples, and the results eliminated them from suspicion. When initially contacted, Woloson refused to provide a DNA sample, but through a twist of events his DNA was obtained. With the assistance of the Michigan State Police (MSP) and the Washtenaw County Sheriff’s Department (WCSD), DNA samples were obtained from cigarette butts found in a vehicle that Woloson had recently owned. Media sources provided conflicting reports regarding the vehicle in question. One report stated that the butts were recovered from a vehicle that Woloson recently sold. Another reported that Woloson loaned his car to a prostitute, but it was never returned—the car was involved in a crime and traced back to Woloson. The first cigarette butts tested were found to be smoked by a woman. Several months later, a second set of butts were tested and the DNA proved to be a definitive match to Woloson, who was arrested on September 23, 2004. That was the date of Frank Schumake’s birthday—Susan’s father—but he died seven years earlier and never had the gratification of seeing justice for his daughter’s murder. The evidence led to Woloson’s conviction in connection with Schumake’s murder. In his closing argument, Jackson County state’s attorney Michael Wepsiec said that “the DNA in this case doesn’t lie. The defendant is the person in this great whodunit. Daniel Woloson is the person who killed Susan Schumake.”

Woloson received a forty-year sentence, but credit for good behavior and time served may mean that he could be released in less than twenty years. He continues to claim that he is innocent and is currently appealing his conviction.

It was new technology that prompted Echols to look into other unsolved cases like that of Deborah Sheppard, who was also an SIU student. According to Carbondale police chief Jeff Grubbs, Echols didn’t pick Sheppard’s case because of any specific reason. Grubbs said that it was part of Echols’s job to investigate any open cases that remained unsolved, and the one involving Sheppard’s murder was just one of several.

It was DNA evidence from Sheppard’s purple shirt that Echols resubmitted for examination that linked the murder to Timothy Wayne Krajcir. According to an article in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, Echols said that investigators who worked on the Sheppard crime scene twenty-five years earlier were not initially going to collect the shirt because it didn’t appear to be linked to the crime. But when they turned her body over, fluid spilled out from her mouth and got on the shirt, so they decided to take it as evidence. The stained shirt was stored and preserved well enough that Echols was able to submit the evidence to the Illinois State Police Forensic Science Laboratory. A forensic scientist was able to develop a DNA profile from the stain on the shirt, which was found to contain seminal fluid. The profile that the lab technician developed was compared to the DNA profiles in the Combined DNA Index System (CODIS).

CODIS is a federally funded computer system that stores DNA profiles created by federal, state, and local crime laboratories throughout the United States, and authorities have the ability to search the database of profiles to identify suspects in crimes. In its original form, CODIS consisted of two indexes, the Convicted Offender Index and the Forensic Index. The Convicted Offender Index contains profiles of individuals already convicted of crimes. All fifty states have passed DNA legislation authorizing the collection of DNA profiles from convicted offenders for submission to CODIS. The Forensic Index contains profiles developed from biological material found at crime scenes.

A DNA profile was able to be developed from seminal fluid on the piece of clothing, and on August 9, 2007, a computerized search of CODIS revealed a match to Krajcir, who was already incarcerated at the Big Muddy River Correctional Center.

On August 21, 2007, Lieutenant Echols and Sergeant Michael Osifcin drove to Ina, Illinois, to question Krajcir in regard to the offense. During the interview, Krajcir denied having anything to do with Sheppard’s murder. The next day, Echols and Osifcin pursued their questioning at a second interview. This time, knowing that the DNA evidence against him was irrefutable, Krajcir finally broke down and admitted that he had committed the crime.

Deborah Sheppard was from Olympia Fields. Deborah was the firstborn child in her family and served as a surrogate mother to her two younger siblings. She loved animals and had an interest in pursuing a career in veterinarian medicine, but when she moved to Carbondale to attend SIU, she majored in marketing.

On April 8, 1982, she was a twenty-three-year-old African American senior who looked forward to her upcoming graduation. Sheppard didn’t know who Krajcir was at the time, but he was also a student at SIU, who was recently paroled despite objections from the Jackson County Prosecutor’s Office. The state’s attorney feared that if Krajcir was released, he had the potential to commit violent, sexual criminal offenses. His intuition proved correct.

Krajcir confessed that he broke into Sheppard’s apartment and then attacked her as she came out of the shower. He said that he threw her down on the living-room floor and raped her. He said that he wore a blue bandana to cover his face, but Sheppard managed to pull it down. After the rape, he strangled her to death. Krajcir told Echols that he had to kill her because she had seen his face, and he didn’t want her to be able to identify him.

In the late evening hours of April 8, Edward Cralle found the front door to Sheppard’s apartment left slightly ajar. Upon entering, he found her naked body lying on the floor, and the phone cord had been cut. After her body was discovered and an autopsy was performed by Dr. Steven Nernberger, of Anderson Hospital in Maryville, Illinois, the Carbondale Police Department issued a statement that there was no indication of foul play connected with her death. Deborah’s father, Bernie Sheppard, was not convinced. His daughter was happy, young, and healthy. He claimed that the original report filed by officers at the scene ruled the death as “suspicious” and a probable homicide. Bernie Sheppard also claimed that the initial report was changed under the orders of Edward Hogan, the Carbondale police chief. Sheppard said that when he asked for an explanation, he was told that it was decided that mistakes made on the initial report were subsequently corrected. Sheppard believed that it was a conspiratorial attempt to cover up the murder. He said that the police did it deliberately because there were a growing number of unsolved homicides in the area at the time, and they did not want to absorb another one.

Over the last decade, there have been many allegations made against police departments for manipulating crime statistics in order to reduce the number in incidents of violent crime. It has been documented that the Patrolmen’s Benevolent Association (PBA) in New York City accused officials in 2004 of reclassifying felonies as misdemeanors, logging in rapes as “inconclusive incidents,” and labeling incidents of attempted murder as simple criminal mischief. In Los Angeles, the Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD) showed a 28 percent reduction in violent crime in 2005 after they reclassified domestic assaults in which the victims suffered minor or no injuries. Several police officers in New Orleans were fired in 2003 after they were accused of downgrading incidents of violent crimes. There is no doubt that this type of unethical and often illegal behavior exists within law enforcement agencies across the country, but Sheppard had no evidence that this was the case in Illinois.

Sheppard also said that because his daughter was black, racism probably played a role in the alleged cover-up. Whether that was true or not, the fact remains that this was only conjecture on his part, and he had no proof to back up his accusation. At the time, he told the Chicago Tribune that he did not care how much time, money, or heartache was involved, he was going to do whatever he could to make sure that his daughter’s killer was found and convicted.

Sheppard’s family had her body flown to Chicago and paid to have Cook County medical examiner Robert Stein perform a second autopsy. Stein determined that she had suffered several blows to the head and was strangled to death. He also found evidence of seminal fluid inside her mouth. Sheppard’s death was now considered a homicide.

Bernie Sheppard said that if it had not been for the fact that he had access to people in prominent positions, his daughter’s death would have been swept under the rug as a natural-death situation, and it would have been forgotten about. Sheppard’s theory of conspiracy and racism is only speculative, and during an interview in 2008, former Carbondale police chief Hogan provided a different version of the events that took place twenty-five years earlier.

Hogan said that precinct sergeant Jim Rossiter was the first police officer to arrive on the scene. After finding Sheppard’s body, Rossiter called a police dispatch operator who, in turn, contacted Hogan. When Hogan arrived at the apartment building, he noted that there was no indication of a struggle. “There were no broken dishes, no broken furniture, and no injuries to the body that were discernable to the naked eye. It was a clean scene,” Hogan stated.

There were four apartments in the two-story building and Sheppard lived on the ground floor on the east side of the structure. A window to the living room was found open. After Sheppard’s death was ruled to be a homicide, Hogan changed his story and said that he initially suspected that the intruder entered through the open window and then waited for Sheppard to come home. He said that Carbondale police investigators collected all the evidence they could find and spent several days questioning other residents in the building and around the neighborhood.

“We did as extensive of an investigation as possible at the time, but, of course, we didn’t have the expertise or equipment that is available today. No fingerprints were found at the scene, and we kept running into blind alleys with nothing breaking in our favor,” Hogan said.

When asked about Sheppard’s accusation that racism contributed to the hindrance of the investigation, Hogan replied that there was no prejudice on the side of the police department.

“If you know Illinois, you’ll know that there are areas in and around Chicago, and then there is the rest of the state. They are two different worlds. Sheppard comes from one of the ‘colored counties’ and much of what he believes is just a figmentation of his hostility. I have no doubt that it appeared like that to him. He called us a bunch of hick country bumpkins that didn’t know what we were doing. The fact is that we did everything we could. If we would have had the technology that exists today, things might have been different at the time, but we did collect all the evidence we found, and we were able to preserve it well enough to allow it to be used when the technology did finally become available,” Hogan said. Despite Hogan’s insistence that there was no element of racism that played a role, his comment about the “colored counties” might indicate otherwise. The real truth of the matter regarding racism and a possible intentional cover-up of the homicide probably lies somewhere between the perspectives of both Bernie Sheppard and Edward Hogan.

Evidence and leads may or may not have been compromised due to the passage of time between the discovery of Sheppard’s body and the official declaration that it should be dealt with as a homicide, but the end result was that despite the efforts of the CPD, they were left with no suspects and no motive for the crime. A Tribune reporter quoted a Carbondale police officer at the time stating, “If we don’t get a break and make an arrest now, we probably never will.”

Once Krajcir was officially charged, Carbondale police chief Bob Ledbetter released a statement in which he quoted, “I must note that this investigation didn’t sit in a box on the shelf as some might suspect. This case was always assigned to a detective over the years, and new leads would be investigated from time to time, always resulting in another frustrating dead end.”

In 2007, when Echols informed Bernie Sheppard that they had at last found the man responsible for killing his daughter, Bernie said that he might finally get a bit of relief knowing who was responsible. Bernie Sheppard also said, “I want to see him executed. I want to sit right there and watch him take his last breath…. That’s what I want.”

Unfortunately for Sheppard, the state of Illinois didn’t have capital punishment in 1982, so according to the statutes of law at the time the crime was committed, Krajcir would only be able to receive a maximum penalty of forty years if he was convicted.

A preliminary hearing for Krajcir was scheduled for September 28, 2007, and it was ordered that his bond remain at $1 million. The date to enter a plea actually took place on October 1, and the courtroom in the Jackson County Sheriff’s Department (JCSD) fell silent as Timothy Krajcir was escorted into the room in handcuffs. Bernie Sheppard attended the hearing to see the man who had killed his daughter. He admitted that his real purpose for attending was to seek vengeance. He didn’t care if it meant spending the rest of his life in prison—he wanted to kill Krajcir. Sheppard didn’t bring a weapon to the hearing. He wanted to feel Krajcir die between his bare hands. The opportunity never presented itself, and with two bad legs, Bernie Sheppard probably wouldn’t have been much of a match against the fit and athletic Krajcir.

Defense attorney Patricia Gross entered a tentative plea of not guilty to the judge. A pretrial date was set for November 13, when the presiding judge would decide if a bench trial or a jury trial would proceed unless a plea of guilty was entered before then. Plea negotiations could now be pursued by the prosecutor, and if an agreement could not be reached, a trial date of December 10 was scheduled.

Despite the new DNA evidence and Krajcir’s confession during his interview with Echols and Osifcin, in the eyes of the law, his plea of not guilty made him innocent unless a judge or jury decided differently.