Читать книгу Predator - Steven Walker - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

4

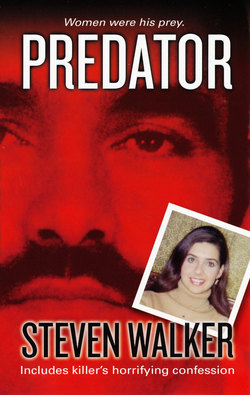

ОглавлениеSheila Cole

November 1977

Cape Girardeau is often described as a big town or a small city, depending on one’s point of view. It hosts a plentiful stock of hotels and motels, bars, and hundreds of choices of places to eat, from fast-food chains to fine-dining establishments. There is a downtown that caters to tourists with a desire to explore American history as well as to the college students who attend the Southeast Missouri State University. There is plenty of free downtown parking available for people who want to visit the unique shops, galleries, and pubs that are nestled along the banks of the Mississippi River. What was not generally plentiful were horrific crimes of murder.

On November 17, 1977, just three months after the Parsh murders, a SEMO State University student was found dead. She was discovered at a rest stop along Illinois Route 3, just south of McClure, Illinois. Her fully clothed body was lying faceup on the floor in the women’s restroom, with two .38-caliber gunshot wounds in her head.

A passing motorist who pulled over at the rest stop discovered the body and anonymously called 911 to report it. Deputy Kenneth Calvert, of the Alexander County Sheriff’s Department (ACSD) in Cairo, Illinois, was the first to arrive on the scene. He saw the body of a fully clothed white female lying faceup on the floor at the north side of the restroom. A wound was clearly visible on the victim’s head, where a large quantity of blood had pooled around it. It did not take long for other officers from the sheriff’s department to arrive.

The scene was photographed and processed by Special Agents Gary Ashman and Connell Smith, of the Illinois Division of the Federal Bureau of Investigation. One bullet was found lodged in the north wall of the restroom. A second was recovered from the floor underneath the victim. Two partial footprints were found near a trash container. A woman’s purse was discovered inside the trash can. The purse contained a photo driver’s license belonging to twenty-one-year-old Sheila Cole, of Crest Oak Lane in Crestwood, Missouri. Also inside the purse was a checkbook. The last entry, dated November 16, was in the amount of $8.97 for a purchase from a Wal-Mart store. Other items recovered from her purse included credit cards, traveler’s checks, a small amount of cash, and some personal items. The motive for her murder was obviously not robbery. There was also a Wal-Mart sales catalog in the purse, which was addressed to Sheila Cole, residing on Sprigg Street, in Cape Girardeau, Missouri.

Once all the evidence was collected from the scene, Alexander County coroner Thomas Bradshaw had the body removed and transported to the Crain-Barkett Funeral Home in Cairo, Illinois.

The Cape Girardeau police were notified of Cole’s murder and were told that she had been living in an apartment located on Sprigg Street, directly across from the police department, and, coincidentally, next door to the convalescent home where Floyd Parsh temporarily lived after his wife and daughter were murdered.

Special Agents Ashman and Smith were accompanied to the Sprigg Street address by Cape Girardeau patrolman Ronald Thomas. When they knocked on the door, they were greeted by Joan Barnard. Barnard said that she shared the apartment with Sheila, Connie Walker, and Jan Gredizer. They were all students at Southeast Missouri State University.

Barnard told the investigators that the last time she saw Sheila was at about 3:30 P.M. the previous day in the apartment. Barnard said that Sheila left at that time to go see her boyfriend, Matthew Sopko, a student who lived in a dormitory on campus. She also told them that Sheila’s bed had not been slept in, and her light blue Chevy Nova was gone.

Cape Girardeau police captain William Stover was able to get a thorough description of Sheila’s car, along with its vehicle identification and license plate numbers, by contacting the university’s security police. The Illinois State Police (ISP) then dispatched that information with a notice that the vehicle should be secured for fingerprints if it was found.

When Matthew Sopko was interviewed, he said that Sheila had picked him up at the dormitory at around 4:00 P.M. and that they went to get something to eat at McDonald’s, and then did some shopping at the Kroger grocery store. Sopko told the investigators that Sheila dropped him back off at the dormitory about an hour later, and that he had not seen or heard from her since. His roommate, William Doyle, confirmed that story. He said that Sopko had been dropped off by Sheila at around 5:00 P.M., and he and Sopko were together until around midnight. Doyle stated that Sopko spent a lot of time at Sheila’s apartment—sometimes as many as three or four nights a week. He also provided investigators with a note that he found on Sopko’s desk. The note read, Sheila, I love you with all my heart. There is nothing I wouldn’t do for you, but there is nothing that I can do for you. I guess you need me like a hole in the head.

John Boyce, who lived in an apartment in the same building as Sheila, said that he remembered seeing her car parked in front of the building sometime between five-thirty and six o’clock that evening.

Gredizer, Sheila’s other roommate, said that she was studying at the kitchen table when Sheila left the apartment again, at around 7:30 P.M., to go to Wal-Mart and pick up some film she had developed there.

Throughout all of these and many other interviews, the timeline of Sheila’s whereabouts remained unbroken. Every minute of November 16 was accounted for, until she had gone to pick up her photos. She was never seen alive again by anyone other than her killer. Sopko laid eyes on her one more time. He was asked to come to the Crain-Barkett Funeral Home to identify her corpse. Later that evening, Dr. Cornelio Katu-big, of Marion, Illinois, performed an autopsy in front of the coroner and Special Agents Ashman and Smith.

DNA technology didn’t exist in 1977. One of the main purposes of an autopsy was to determine the cause and time of death, not to collect other evidence to solve a murder. In Sheila Cole’s case, the cause of death was determined to be a result of a gunshot wound to the back of the neck and one to the right side of the bridge of the nose. The autopsy report provided no other information except that there was no evidence of injury to her external genitalia.

Sergeant Brown, of the Cape Girardeau Police Department, said that the hurried process of the autopsy and the embalming of Sheila Cole’s body were detrimental to discovering any possible physical evidence that might have led them to a suspect. He said that the body was embalmed even before some investigating authorities were notified of her death. As a result, physical evidence that would have been beneficial may have been lost.

Patrolman Sam Light reported for duty at 11:00 P.M. on November 17. During his shift, he reported that he observed a blue Chevy Nova in the Wal-Mart parking lot. Detective John Brown relayed this information to the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), and late the next morning, on November 18, Special Agents Ashman and Smith located a light blue 1976 Chevy Nova in the Wal-Mart parking lot located on South Kings Highway in Cape Girardeau. (Today it is a Hobby Lobby store.) The serial number and license plate matched Cole’s car. The keys were left in the ignition, and the driver’s door was unlocked. It had rained during the evening of November 16, and the windshield wipers were left in the on position. A paper bag in the trunk of the vehicle contained photographs that were recently developed at Wal-Mart and a sales receipt totaling $8.97, corresponding with the last notation in Sheila Cole’s checkbook.

An employee at the nearby Service Laundromat told investigators that she left work at approximately 10:45 on the evening on November 16 and that she believed that the blue Nova was parked in the Wal-Mart lot at that time.

A Wal-Mart employee told Brown that at about 10:30 A.M. on November 17, she heard a page over the store’s public-address system asking for the owner of a blue 1976 Nova to go to the service desk. Apparently, nobody showed up.

The entire car was processed for the collection of evidence. Items sent to the Southeast Missouri Crime Laboratory for examination included hairs found in the vehicle, the floor mats, a gum wrapper, and the contents of the ashtray. No fingerprints were found on the cigarette butts or the gum wrapper. There were only two brands of cigarettes found in the ashtray; the brand that Sheila smoked and that of her boyfriend, Matthew. Hair samples found in the car matched those of Sheila, Matthew, and Sheila’s roommate Connie Walker.

Sergeant John Brown, of the Cape Girardeau Police Department, said that he had no reason to believe that the murder of Sheila Cole was related to the Parsh murders, but for good measure, bullets retrieved from the Parsh house were sent to the FBI lab in Washington, DC, for comparison.

A white pair of panties belonging to Cole was sent to the Bureau of Scientific Services in DeSoto, Illinois, for analysis. No hair or fibers were found. The crotch area was heavily stained, but chemical tests failed to confirm if that was caused by seminal fluid.

No further lab work was authorized unless additional evidence became available. After dozens of additional interviews, up to this point, investigators in both Missouri and Illinois had exhausted their leads, and they still were no closer to discovering who was responsible for the murders. That did not deter them from continuing to investigate every avenue available, no matter how insignificant it appeared.

One witness, Jess Norton, claimed that he had been traveling north on Illinois Route 3 at around 11:00 P.M. after he crossed the Mississippi River from Missouri and entered Illinois. He said that the blue midsized car in front of him pulled into the rest stop where Cole was murdered. He described the passengers as a male and a female, and his description of the female was similar to that of Sheila Cole. He was subsequently hypnotized by an FBI investigator and repeated the same information.

There was no physical evidence at the time to prove that Cole was a victim of rape. Robbery was ruled out because the killer had not taken the traveler’s checks from her purse. Because there was so little evidence left at the scene, authorities could not even confirm if Cole’s assailant was a man or a woman. Special Agent Ashman was quoted by the Missourian newspaper as saying, “People must realize that we have to have something to work on. We’re not miracle workers who can pull a suspect out of thin air.”

With no apparent motive in the slaying, investigators said that locating the handgun and tracing it through its serial number might be the only link to discovering the coed’s killer. It seemed like a long shot, but detectives from the Illinois Division of Investigation called in a septic tank cleaning service to pump out the waste matter from the pits under both the men’s and women’s toilets at the McClure rest area. Once the pits were emptied, investigators probed the debris with claw arms and long-handled shovels to search for a handgun. At best, this might have been considered an unsavory task, but Ashman explained that “it’s just something we have to check out. Experience has taught us that you can’t second-guess these killers.” Unfortunately, the attempt to recover the gun used to kill Sheila Cole was unsuccessful. There was still hope that some useful information might be revealed from the bullets that were recovered at the scene.

Sheila’s mother and father were obviously distraught at the news of their daughter’s death. Sergeant Brown said that for a long time afterward, Harold Cole, Sheila’s father, would drive to Cape Girardeau from his home in Crestwood almost on a weekly basis.

“He would just drive around, hoping that somehow he would be able to find Sheila’s killer. I think he knew that he never would, but he couldn’t just sit around feeling helpless. He needed to feel like he was doing something,” Brown said.

According to everyone who knew Sheila, she was a sweet girl who got along well with just about anyone. She had a contagious smile and an optimistic attitude. As a senior at SEMO State University, Sheila was a member of the Pi Kappa Alpha Little Sisters at the university and she enjoyed school activities. All her life, she had a fondness and fascination with animals, so she majored in zoology with a minor in chemistry. Her chosen course of study was academically challenging, but Sheila was very studious. She was also a social person who liked to party with her roommates and circle of close friends, but she was conservative with her money. Her roommates said that Sheila never had any financial problems and always found some type of job to make money during the summer months when she returned to live with her family in Crestwood.

During a coroner’s inquest on December 1, 1977, her father, Harold, testified that Sheila always acted conservatively and responsibly when it came to her possessions. “I’d like to make this point very strongly,” he said. “If her keys were found in her car, then she did not leave the car voluntarily. She always took her keys and locked the car.”

Her roommate Connie Walker also testified that Sheila was fastidious in her habits. Walker said, “Sheila’s car was her pride and joy. She took good care of it. She was always telling me to lock the door.”

Harold Cole said that the only enemy the family might have was a woman from Arcadia, Missouri, who was involved in a lawsuit over some money that his wife’s uncle gave to her. He also said that Sheila dated a boy named Jerry Seegers during her first year of college at St. Louis Community College (STLCC)—Meramec in Kirkwood, but that he moved on to attend Southern Illinois University in Carbondale, Illinois, when Sheila moved to Cape Girardeau.

Dixie Gail Keena, a friend of Sheila’s, told police about another former boyfriend named James Zeiser, who belonged to the Sigma Tau Gamma Fraternity. Each person that investigators interviewed led them to another interview, and another.

Lester Burchyett told investigators that Bob Lusk, of Ralph Edwards Realty, told him that Sheila had inquired about finding a house in McClure, Illinois. When police contacted Ralph Edwards, they were told that Sheila had not contacted their agency.

Round and round it went as dozens of interviews were conducted throughout the next month, and still, the police were no closer to solving the case. They did not even have a suspect or a motive.

Matthew Sopko agreed to submit to a polygraph examination December 2 at the Cape Girardeau Police Department. The results of that examination indicated that Sopko had no involvement in the murder of Sheila Cole.

During the course of the investigation, Illinois state troopers were told of women who claimed they had been stalked by strange men, a member of a mercenary group that killed “dirty women,” and a drunk man who sat at the bar in the Down’s Club and told the bartender he was going to kill somebody. It seemed that everyone knew somebody who might be the killer.

Special Agent Richard Evans, of the Illinois Department of Law Enforcement (IDLE), tracked down Sheila’s former boyfriend Jerry Seegers in Carbondale. He lived at the Tan Tara Mobile Home Park and still attended Southern Illinois University, where he majored in photography.

Seegers told Evans that he had not seen Sheila since he last visited her about a year earlier. He said that they had dinner together, went to the Trail of Tears State Park, and then spent the rest of the evening watching television in his motel room. He added that they did not have sex.

Seegers said that Sheila told him that she did not care for one of her roommates (she was living in the dormitory at that time) and that she was becoming disillusioned with Sopko because he “hassled” her about her foul language. He added that Sheila was not too fond of her brother, either. Seegers told Evans that he had learned of Sheila’s death from a television news report and that he would assist investigators in any way that he could.

Alexander County sheriff Donald Turner reported that a man named Charles Clifton told him that another man, Dean Bagby, came into the Hub Tavern on the morning of November 17 and said that he was in terrible trouble because he had shot someone. When Bagby was interviewed, he denied making that statement. Round and round it continued, but police were still no closer to the truth.

It was not until near the end of December that ballistic test findings determined that it was probable that the same type of gun used to kill Sheila Cole was also used in the Parsh murders. The lab examiner reported that in both cases the bullets appeared to be Remington-Peters .38-caliber 158-grain round-nose bullets that were probably fired from a Charter Arms undercover model pistol. On December 29, the cases were combined.

In a prepared statement, the Cape Girardeau Police Department released to the media that the Parsh and Cole murders might be linked to a single “psychotic” killer. The statement said that in addition to similarities in the ballistic test report, the apparent lack of a normal motive in the slayings—such as robbery, rape, or revenge—has led authorities to theorize that one psychotic individual could be responsible for all three murders.

Chief Gerecke said at the time, “We don’t want to be alarmists, but I feel it is our duty to alert the public.” He added that his own daughter was visiting during the holiday break from her school in Texas, and he had told her not to go out alone or pick anyone up while she was staying in the area.

The bodies of Mary and Brenda Parsh were so decomposed when they were discovered that no useful physical evidence could be recovered from their autopsies that would aid investigators to solve the case. In contrast to the longevity that contributed to the accelerated decomposition of Mary and Brenda Parsh as a detrimental factor, it may have been haste that contributed to a lack of evidence in the Sheila Cole case. According to Sergeant Brown, Cole’s body was already in the process of being embalmed before some investigating authorities were even notified of her death.

While the ballistic test showed similarities in the bullets used in the Parsh and Cole murders, the report did not provide definitive proof that the same weapon was used in both cases. Federal, state, and local authorities worked together to search for another common thread that might link the victims.

Sheila Cole lived in an apartment building that was located next door to the nursing home where Mr. Parsh lived for several months after his wife and daughter were killed, but he said that he had never spoken to or even had known who Cole was.

Before moving to Milwaukee, Wisconsin, Brenda Parsh lived and worked in St. Louis. Cole’s family lived in Crestwood, which is located outside of St. Louis, but there was no indication that they ever ran into each other or even knew each other. In considering any possible connection with the background of the victims, Brown said, “Nothing seemed close or to overlap at all.” He added, “That was just about the time that ‘Son of Sam’ was prominent in the newspapers and maybe that triggered something. If we have a true psychotic here as well, he might strike again.”

1978–1981

I just went nuts. Back in ’77 and ’78, I think I just went a little crazy.

—Timothy Wayne Krajcir