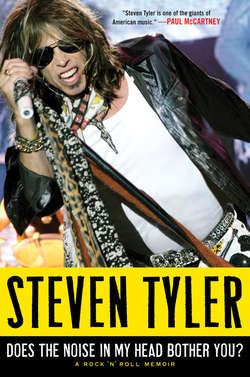

Читать книгу Does the Noise in My Head Bother You?: The Autobiography - Steven Tyler - Страница 6

ОглавлениеCHAPTER ONE

Peripheral

Visionary

I was born at the Polyclinic Hospital in the Bronx, March 26, 1948. As soon as I could travel my parents headed straight out of town to Sunapee, New Hampshire, to the little housekeeping cottages they rented out every summer, kind of an old-fashioned bed-and-breakfast deal only it was 1950. I was put in a crib at the side of the house. A fox came by and thought I was a cub, grabbed me by the scruff of my diaper, and dragged me into the woods. I grew up with the animals and the children of the woods. I heard so much in the silence of the pine tree forests that I knew later in life I would have to fill that void. The only thing my parents knew was that I was out there somewhere. They heard me cry in the forest one night, but when they came up to where I was, all they saw was a big hole in the ground, which they thought was the fox’s den. They dug and dug and dug, but all they found was the rabbit hole I’d fallen into—like Alice.

Trow-Rico Lodge and the lawn I was mowing when Joe Perry drove up, summer of ’69. (Ernie Tallarico)

And like Alice I entered another dimension: the sixth dimension (the fifth dimension was already taken). Since then, I can go to that place anytime I want, because I know the secret of the children of the woods; there’s so much in silence when you know what you’re hearing—what dances between the psychoacoustics of any two notes and what reads between the lines is akin to the juxtaposition of what you see when you look in the mirror. My whole life has been dancing between these worlds: the GOAN ZONE, the Way-Out-o-Sphere and . . . the UNFORTUNATE STATE OF REALITY. In essence, I call myself a peripheral visionary. I hear what people don’t say and I see what’s invisible. At night, because our visual perception is made up of rods and cones, if you’re going down a dark path, the only way to really see the path is to look off and see it in your peripheral vision. But more on this as we progress, regress, and digress.

When I finally got pulled out of the rabbit hole, my parents brought me back to the third dimension. Like all parents they were concerned, but I was afraid to tell them that I have never felt more comfortable than being lost in that forest.

In Manhattan we lived at 124th Street and Broadway, not far from the Apollo Theater. Harlem, man. If the first three years of your life are the most informative, then surely I needed to hear that music, and I was inspired by the noise coming out of that theater. It had more soul than Saint Peter.

A few years ago I was back at the Apollo, and saw the park where my mom had pushed me in my carriage. My first visual memory is from THAT PARK: trees and clouds moving above my head as if I were floating above the earth. There I am, a two-year-old astral-projecting infant. At age four, I remember going to get a gallon of milk with two quarters, walking with my mom hand in hand through passages and corridors of the basement of our building and through tunnels into the adjoining building where the milk machine was. I thought I was . . . God knows where. I might as well have been on Mars. Ah, it was the mysterious world of childhood, where someone is always leading you by the hand through a dark passageway and into a brand-new world just waiting for the child’s overactive imagination to kick in.

My mother lit the fire that would keep me warm for the rest of my life. She read me parables, Aesop’s Fables, and Rudyard Kipling’s Just So Stories. Children’s tales and nursery rhymes from the eighteen hundreds, nineteen hundreds: “Hickory Dickory Dock,” Andrew Lang’s The Nursery Rhyme Book, Hans Christian Andersen, Helen Bannerman’s Little Black Sambo. So great! Never mind the “Goose That Laid the Golden Egg!” My mom would read me all these stories every night at bedtime. But one night when I was around six, she stopped.

Happy days—Mom and me and Crickett, my Toy Fox Terrier, 1954. (Ernie Tallarico)

“You gotta learn how to read ’em yourself,” she said. Up until then I’d been reading along with her as she pointed to the words. We did this for months until she knew I kinda had the idea, then suddenly there’s no Mom looking over my shoulder. She just left the book by my bed and I became distraught. “Mom, I wanna hear the stories. Why won’t you read to me anymore?!” I said. And then one night I thought to myself, “Uh-oh, now I gotta get smart.” Naah. . . . I’ll just become a musician and write my own stories and myths . . . Aeromyths.

Mom used to tell me of a man she’d seen on the Steve Allen Show, in 1956 when I was eight. His name was Gypsy Boots. He was the original hippie, a guy who lived in a tree with hair down to his waist and who promoted health food and yoga. Gypsy was the protohippie. In the early thirties he had dropped out of high school, wandered to California with a bunch of other so-called vagabonds, lived off the land, slept in caves and trees, and bathed in waterfalls. I was totally seduced by that lifestyle. Boots’s message was this: As primitive as his world seemed, he wanted people to think that he would live forever. Hey, he almost did, dying just eleven days before his ninetieth birthday in 1994.

Next in my life came a bohemian composer named Eden Ahbez, who wrote a song called “Nature Boy” (which my mom heard on a Nat King Cole record). He camped out below the first L in the Hollywood sign, studied Oriental mysticism, and, like Gypsy Boots, he lived on vegetables, fruits, and nuts. My mom sang that song to me before I went to sleep. I’ll never forget how it made me think that I was her nature boy.

The song tells the story of how one day an enchanted wandering Nature Boy—wise and shy, with a sad, glittering eye—crosses the path of the singer. They sit by the fire and talk of philosophers and knaves and cabbages and kings. As the boy gets up to leave he imparts the secret of life: To love and be loved is all we know and all we need to know. With that Nature Boy vanishes into the night as mysteriously as he had come.

Unfortunately the people who own the rights to “Nature Boy” won’t let me publish the actual words to the song in this book (still, you can just Google them), but I promise it will be on my solo album come hell or high water.

Then there was Moondog. What a fantastic character, a blind musician who dressed up like a Viking with a helmet and horns and a spear to match. He hung out on the corner of Fifty-sixth Street and Sixth Avenue. I saw and smelled him every morning on my way to school. Oddly enough, he lived up in the Bronx, apparently in the woods, back behind the apartment buildings I grew up in. Was that a coincidence or was that God secretly telling me, “Steven, thou shalt become the Moondog of your generation”? Or at least the leader of a rock ’n’ roll band.

What I heard about Moondog was that he wrote “Nature Boy,” but what do I know? Maybe Eden Ahbez is Moondog spelled backward. . . .

My mother’s birth name was Susan Rey Blancha. At sixteen she joined the WACs (Women’s Army Corps). She met my dad while they were both at Fort Dix in New Jersey during World War II. One night he had a date with a woman who was rooming with my mom. The roommate stood him up, and instead he was greeted by my mother, who happened to be playing the piano at the time. My dad walked over to her and said, “You’re playin’ it wrong.” It was love at first fight! They got married and had lil ol’ Lynda, my sister, and lil ol’ me came two years later. Ha-ha! That’s my mom, that’s my dad, and that’s why I’m so fuckin’ detail-oriented—and such a maniac. I got the traits that I don’t want and the ones I do. Because you’re an offspring, you pick up those traits unconsciously, in case you haven’t noticed. You become your mom!

My mother, Susan Rey Blancha, at eighteen in 1932. (Ernie Tallarico)

So that’s how I happened, 1948, a rare mixture of classical Juilliard boy meets country pinup girl, who, by the way, looked like a cross between Jean Harlow and Marlene Dietrich with a tinge of Elly May Clampett. And if God’s in the details—and we know She is—then I’m the perfect combination. I’m the N in my parents’ DNA. So now, if anyone’s mad at me and calls me a dick, I know they really mean Fort Dix. My daughter Chelsea always thought God was a woman from the day she was born. It was so nurturing hearing that from a child, that God would have to be a woman, that I just never questioned it. (No wonder I keep watching Oprah.)

Chelsea Anna Tyler Tallarico on our rope swing, Sunapee, New Hampshire, 2008. (Steven Tallarico)

Mom was a free spirit, a hippie before her time. She loved folktales and fairy tales but hated Star Trek. She used to say, “Why are you watching that? All the stories are from the Bible . . . just six ways from Sunday. Get the Bible!” And I thought, “Oh, boy, that’s just what I wanna do after I’ve rolled a doobie and I’m smokin’ it with Spock.” And by the way, that’s why teenagers today go, “Whatever!” But you know—and I can only admit this in the cocktail hours of my life—SHE WAS RIGHT!!!!! Isaac Asimov’s I Robot, Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World, that’s where they got their inspiration. In the same way that Elvis got his sound from Sister Rosetta Tharpe (I dare you to YouTube her right now), Ernest Tubb, Bob Wills, and Roy Orbison. And they, in turn, begat the Beatles and they begat the Stones and they begat Elton John, Marvin Gaye, Carole King, and . . . Aerosmith. So study your rock history, son. That be the Bible of the Blues.

I was three when we moved to the Bronx, to an apartment building at 5610 Netherland Avenue, around the corner from where the comic book characters Archie and Veronica supposedly lived (I guess that makes me Jughead). We lived there till I was nine—on the top floor, and the view was spectacular. I would sneak out the window onto the fire escape on hot summer nights and pretend I was Spider-Man. The living room was a magical space. It was literally eight feet by twelve! There was a TV in the corner that was dwarfed by Dad’s Steinway grand piano. There’s my dad sitting at the piano, practicing three hours every day, and me building my imaginary world under his piano.

Me and Dad, 1958. It did snow more back then. (Ernie Tallarico)

It was a musical labyrinth where even a three-year-old child could be whisked away into the land of psychoacoustics, where beings such as myself could get lost dancing between the notes. I lived under that piano, and to this day I still love getting lost under the cosmic hood of all things. Getting into it. Beyond examining the nanos, I want to know about what lives in the fifth within a triad . . . as opposed to DRINKING a fifth! I’ve certainly got the psycho part . . . now if I could only get the acoustic part down (although I did write a little ditty called “Season of Wither”).

And that’s where I grew up, under the piano, listening and living in between the notes of Chopin, Bach, Beethoven, Debussy. That’s where I got that “Dream On” chordage. Dad went to Juilliard and ended up playing at Carnegie Hall; when I asked him, “How do you get to Carnegie Hall?” he said, like an Italian Groucho, “Practice, my son, practice.” The piano was his mistress. Every key on that piano had its own personal and emotional resonance for him. He didn’t play by rote. God, every note was like a first kiss, and he read music like it was written for him.

I remember crawling up underneath the piano and running my fingers on top of the soundboards and feeling around. It was a little dusty, and as I was looking up, dust spilled down and hit me in the eyes—dust from a hundred years ago . . . ancient piano dust. It fell in my eyes and I thought, “Wow! Beethoven dust—the very stuff he breathed.”

It was a full-blown Steinway grand piano, not a little upright in the corner—a big shiny black whale with black and white teeth that swims at the bottom of my mind and from a great depth hums strange tunes that come from I know not where. 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea had nothing on me.

Later on, I went back to visit 5610 Netherland Avenue. I knocked on the door of apartment 6G, my old apartment. It had been years, and the man who answered was drunk and in his underwear and undershirt.

“Dad?” I asked. He cocked his head like Nipper, the RCA dog.

“Hi, I’m—” I started to say.

“Oh, I know who you are,” said he. “From the TV. . . . What are you doin’ here?”

“I used to live here,” I said.

“Well raise my rent!” said he.

So I went in and looked around, and doesn’t it always seem that the apartments we all grew up in are so much smaller compared to how they felt thirty years ago? My god, the kitchen was tiny, four by six! The bedroom I grew up in with my sister, Lynda, and my parents’ master bedroom facing the courtyard—you couldn’t have changed your mind in there, never mind your clothes. How the hell did my father get a Steinway grand into that living room? So weird seeing this very tiny apartment with an even smaller black-and-white-screen TV on which I’d watched in wide-eyed abandon shows like The Mickey Mouse Club and The Wonderful World of Disney, which premiered on October 27, 1954. So between growing up at three underneath a piano and seeing my black-and-white television world turn into color by the age of six, that was enough right there to prepare me for life. I couldn’t wait to jump into the middle of it.

My father, Victor Tallarico, 1956. (Ernie Tallarico)

My dad played those sonatas with so much emotion it vibrated into my very bones. When you hear that music from beginning to end day after day, it becomes embedded in your psyche. Those notes vibrate in your ears and brain. So for the rest of your life your emotions can be easily subliminally tapped into by music.

Most humans who are panning for gold—looking for that ecstatic moment—first find it in their own sexuality; then they have an orgasm and whoops, it’s over. Now, imagine someone exploring, perhaps in search of their destiny. He stumbles upon a cave and out of sheer curiosity crawls inside and then looks up—it’s all glittering and sparkling, and for that first moment I was in Superman’s North Pole crystal palace cave and the crystals resonated with Mother Earth’s birthing cries.

I didn’t know what I was hearing, and didn’t understand then where it all came from. It didn’t matter. I wanted to be a part of that. Little did I know, I was. It was pure magic. My dad manifested those crystal moments playing the notes of those sacred sonatas. It was like a mixture of Yma Sumac and the songs of humpback whales—these godlike sounds came showering down on me.

Dad at the Cardinal Spellman High School graduation in the Bronx, 1965. (Ernie Tallarico)

Just recently my dad came over to the house—he’s ninety-three now! And I sat down next to him at the piano and he played Debussy’s Clair de Lune. It was so much deeper than anything I have ever done or ever will do. It was so deep and invoked so much of that early emotion laid on top of my adult emotions that I wept like a baby. I remember that when I first heard it as a child I almost stopped breathing. Sometimes you can’t appreciate how fortunate you are until you look back and get to glance into the what-it-is-ness and see how it all reflects off from whence you came. I started there, so now I’m here. I guess we’re all here . . . ’cause we’re not all there.

Sunapee, New Hampshire, was where I spent my summers as a kid. Driving up to Sunapee we’d go past Bellows Falls and Mom would say, “Bellows Falls? Fellow’s Balls!” There was so much to my mother. Like the way she’d get me to eat my peas. “Whatever you do, do not eat those!” And I gave her a frog smile.

A few years later, say around 1961, when I’d call for my mother from the other side of the house, my mom would go, “Yo! Where are you? Where’d you go?” Now I wonder where she’s gone. She was a beautiful Philadelphia Darby Creek country girl who came to the city to bring us up, let me have long hair in school, argued with the principals, drove us to our first club dates, and loved and nurtured me—the whoever I was and/or wanted to be.

In the fifties, it would take us seven hours to go from New York up to New Hampshire because in those days it was all on back roads (there were no highways). But the ride up to Sunapee was filled with fantastic roadside attractions. A giant stone Tyrannosaurus rex on the side of the road, wooden bears, Abdul’s Big Boy, and the Doughnut Dip, with a huge concrete doughnut outside.

Trow-Rico, our summer resort in New Hampshire, was named after Trow Hill, a local landmark, and Tallarico, my father’s name, just smushed together. The cottages were on 360 acres of nothing but woods and fields. It was my grandfather Giovanni Tallarico’s dream when he came over from Italy in 1921 with four other brothers. Pasquale was the youngest, a child prodigy on the piano. Giovanni and Francesco played mandolins. Michael played guitar. They were a touring band in the 1920s—it’s where I get my on-the-road DNA. I’ve seen brochures for the Tallarico Brothers—they performed in giant hotels with huge ballrooms in places like Connecticut and Detroit. They went from New York by train to these hotels all over the country and played their type of music, to their type of people. Sound familiar?

Where it all began . . . or, why I must love to tour.

My mother’s father—that was another story. He got out of Ukraine by the skin of his teeth. The family owned a horse-breeding ranch. The Germans invaded and machine-gunned the family down in front of my grandfather. “Everyone out of the house!” Bb-r-r-r-r-a-t! They gunned down his mother, father, and sister. He got away by jumping down a well and managed to grab the last steamer to America.

Trow-Rico is where I spent every summer of my life until I was nineteen. On Sundays my family would throw a picnic for the guests. My uncle Ernie would cook steaks and lobsters on the grill, and we’d make potato salad from scratch. We served all the guests—which came to what? eight families, some twenty-odd people—in our heyday. After dinner, while the sun was going down, we’d fill in the trailer with hay, attach it to the back of a ’49 Willys Jeep, and take everybody on a ride all over the property. We also had a common dining room where we served them breakfast and dinner, and guests would do lunch on their own, all for, like, thirty dollars a week. Sometimes six dollars a night. And when the people left, my whole family got pots and pans out of the kitchen and banged them all together—behold the origin of your first be-in!

Summer of 1954 at Trow-Rico. I’m at the top on the left, Lynda is in the straw hat, and Sylvia Fortune, my first girlfriend, is on the right with her legs crossed. I was infatuated with her. . . . (Ernie Tallarico)

As soon as I was old enough, they put me to work. First it was clipping hedges. When I snapped back, “What do I have to do that for?” my uncle said, “Just make it nice and shut up.” He used to call me Skeezix. He’d spent most of World War II in the Fiji Islands, so he knew how to take care of business and anything else that gave us any trouble. I helped him dig ditches and put in a water pipeline over a mile of mountain and dug a pond with my bare hands. I washed pots and dishes at night and mowed the lawns with my father when I was old enough to push a mower. I cleaned toilets, made the beds, and picked up all the cigarette butts that the guests left behind.

We would rake up the hay with pitchforks and put it in the barn below the lower forty. The downstairs of the barn was empty except for maple syrup buckets and wooden and metal taps for the trees that some family had left before we lived there. It was quite an adventure going down there—full of spiderwebs, stacks of buckets, glass jars, and artifacts from the twenties and thirties—all those dusty, rusty things kids love to get into—me in particular.

Upstairs in the barn, there was a hayloft door with an opening where you’d load the hay in and out. I could climb up there and jump down from the rafters of the ceiling. I did my first backflip in that barn, because the hay was so soft, it was like landing on, well, hay. I always kept an eye out for pitchforks left behind. Land on one of those suckers and I would have learned how to scream the way I do now . . . twenty years earlier.

Before I could go to the beach with the rest of the guests I had to finish doing my chores. After a while I came up with a plan. It was called: get up earlier.

Every Tuesday, Thursday, and Saturday during the summer my father played the piano at Soo Nipi Lodge along with my uncle Ernie on sax. They had a trumpet player named Charlie Gauss, a stand-up bass player named Stuffy Gregory, and a drummer who will go unnamed. Soo Nipi Lodge—which today would probably be called Snoop Dog Lodge—was one of the classic old hotels, like the one in The Shining: all wooden and splendiferous and huge, with dining rooms and decks outside with rocking chairs and screened-in porches. Chill central by today’s standards. They began building these resorts in the 1870s, when horses and buggies brought the guests from the train station to the hotels. The only thing missing was the musicians to play music and entertain the guests—and this is probably how the Tallarico brothers came to buy the land there.

During Prohibition, people would take the train up from New York to Sunapee, and the booze would come down from Canada. Some folks drank, some didn’t. Maybe they came up for the weekend to see the leaves turn, but I have a funny feeling they got on the train for a quick weekend away—take horse-and-buggy rides, stay at the big hotels, and cruise in the old steamboats. The ones in Sunapee Harbor today are replicas of the original ones from a hundred years ago. Very quaint. Ten miles up the road was New London, the original Peyton Place, where, oddly enough, Tom Hamilton was born. But then again, it all makes perfect sense to me now.

On Sunday nights, Dad would give recitals at Trow-Rico. People from miles around would come over to hear him, and my grandma, my mother, and my sister would play duets. All the families that came up had kids, and Aunt Phyllis would holler, “C’mon, Steven, let’s put on a show for them!” Downstairs from the piano room was the barn’s playroom: Ping-Pong, a jukebox, a bar, and, of course, a dartboard. There was also a big curtain across one corner of the room that made a stage where my aunt Phyllis taught all the kids camp songs like “John Jacob Jingleheimer Schmidt” and the “Hole in the Bucket” song. I would pantomime to an old 78 recording of “Animal Crackers.” It was an evening of camp-style vaudeville. For the finale, we hung a white sheet in front of a table made from two sawhorses and a board. Someone from the audience would be brought back to lie on the board, and behind them a giant lamp cast shadows on the sheet. My uncle Ernie would perform an operation on the person lying down, pretending to saw him in half and eventually pull out a baby—quite horrifying and hilarious to the audience. It was all very tongue-in-cheek but certainly the beginning of my career.

We must have done a hundred and fifty or more of those shows over the years. I was a serious ham. I’d do cute things kids can get away with—especially to adoring relatives. It was like something from a Mickey Rooney movie. I’d learned all the lyrics to that song “Kemo-Kimo.”

Keemo kyemo stare o stare

Ma hye, ma ho, ma rumo sticka pumpanickle

Soup bang, nip cat, polly mitcha cameo

I love you

And then I’d add something like “Sticky sticky Stambo no so Rambo, had a bit a basket, tama ranna nu-no.” What the hell was that? The beginning of my love for real out-there music and crazy lyrics.

Before I got involved in doing chores at Trow-Rico, before I discovered girls and pot and playing in bands, I had a great life in the woods with my slingshot and BB gun. As soon as we got up there, I’d be gone in the woods and fields. And I never came back till dinnertime. I was a mountain boy, barefoot and wild. I walked through the woods, looked up at the trees, the birds, the squirrels—it was my own private paradise. I’d tie a stick to a rope and make a swing from any tree branch. I was brought up that way, a wild child of the woods and ponds. But of course, nobody believes that about me. They don’t know what to think when I say, “You know, I’m just a country boy.”

1961—we all gotta start somewhere. . . . (Ernie Tallarico)

No waves, no wind. If you go into a recording studio that’s soundproofed, something just feels wrong to your ears. Especially when they close the door—that’s sound deprivation, it’s anechoic, without echo, without sound. Not so in the woods. In that silence I heard something else there, too.

I lost all that mystery when I was on drugs. Coming out of that din I was able to feel my spiritual connection to the woods again. Drugs will steal you like a crook. Spirituality, over. I could no longer see the things I used to see in my peripheral vision. No periphery, no visions.

I used to go up in the woods and sit by myself and hear the wind blow. As a kid, I’d come across places where the woodland creatures lived. Tiny human creatures. I’d see mossy beds, cushions of pine needle, nooks and crannies under the roots of upturned trees, hollow logs. I’d look around for elves, because how could it be that beautiful and strange and nobody live there! All of this tweaked my imagination into such a state that I knew there was something there besides me. If you could sleep on moss that thick it would be bliss. I’d smell that green grass. I would see a natural little grotto in the woods and say to myself, “That’s where their house must be.”

A few years ago I found a moss bed for sale at this lady’s little store in New London. The place was full of nature stuff—and had a big wooden arch in front and giant bird wings. The bed is made of twigs, with a moss mattress, grouse feathers for pillows, a wooden nest, an ostrich egg cracked in half with a little message on it, and the prints of the fairies that were born on the bed. We kept it in the house so my two children, Chelsea and Taj, would see it and just know that fairies were born on that bed. They’d say, “For real?” and I’d say, “For real.”

I bought the two fields I used to go walking in. I haven’t gone out into the woods lately to see if they’ve been touched; I’m afraid to find out if it’s all still there as I remember it. But I grew up with these creatures. I was alone in the forest but I was never lonely. That’s where my first experiences of otherness came from, of the other world. My spiritual ideas didn’t come from the Lord’s Prayer or church or pictures in the Bible, they came from the stillness. The silence was so different from anything I would ever experience. The only noise that you heard in a pine tree forest was the gentle whistling sound of the wind blowing through the needles. Other than that, it’s just quiet . . . like after a fresh snow. . . . It really quiets down in the woods . . . cracking branches . . . nothing. It’s like when I took acid—I felt the wind brushing against my face although I knew I was in the bathroom and the door was closed. This was Mother Nature talking to me.

I would walk through the woods and walk and walk. I would find chestnut trees, fairy rings of mushrooms, bird’s nests made with human hair and fishing line. I would imagine I was in the jungle in Africa and climb up on the gates at the entrances to the big estates and sit on the stone lions (until someone shouted, “Get down from there, kid!”).

That’s where my spirit was born. Of course I got introduced to spirituality through religion, too, from the Presbyterian Church in the Bronx and my choir teacher, Miss Ruth Lonshey. At the age of six, I learned all the hymns (and a few hers). I fell in love with two girls on either side of me in the choir. And of course they had to be twins. I remember being five and sitting next to my mother in a pew at that church, looking up at the altar that held the Bible and a beautiful golden chalice, with the minister looming over it. There was a golden tapestry that hung down to the floor with a crucifix embroidered on the front. I was all wrapped up in the tradition of getting up, sitting down, getting up, singing, sitting down, praying, singing, praying, getting up, praying, singing, and hoping all this would take me somewhere closer to heaven. I thought for sure God must be RIGHT THERE under THAT altar. Just as I’d thrown a blanket over the dining room chairs to create a fortress, a safe, powerful place, kinda churchlike, with the added bonus of imagination. WOW, all of this combined together in one beautiful moment of ME, feeling GOD. But then I’d met Her once before in the forest.

I would walk in Sunapee with a slingshot in my back pocket over the meadow and through the woods until I got lost . . . and that’s when my adventure would begin. I would come upon giant trees so full of chestnuts that the branches would bend, bushes full of wild blackberries, raspberries, and chokecherries, acres of open fields full of wild strawberries in the grass—so much so that when I was mowing the lawn, it smelled like my mom’s homemade jam. I would find animal footprints, hawk feathers, fireflies, and mushrooms in the shape of Hobbit houses that I was told were left by Frodo and Arwin from Lord of the Rings. Incidentally, those were the same mushrooms that I would later eat and that would magically force my pen to write the lyrics to songs like “Sweet Emotion.” In choir, I was singing to God, but on mushrooms, God was singing to me.

I pretended I was a Lakota Indian with a bow and arrow—“One shot, one kill”—only I had my BB gun—“One BB, one bird.” Me and my imaginary buddy Chingachogook, moving silently through the woods. I was a deadeye shot; I’d come back after an afternoon of killing with my slingshot and Red Ryder BB gun with a string of blue jays tied to my belt. That part wasn’t imaginary. I had watched every spring how blue jays raided the nests of other birds and flew away with their babies. My uncle had told me that blue jays were carnivorous, just like hawks and lawyers.

I’d go out fishing with my dad on Lake Sunapee in a fourteen-foot, made-in-the-forties, very antique, giant wooden 270-pound rowboat that only a Viking could lift. The handles on the oars alone were thicker than Shaq at a urinal. You’re out in the center of the lake, sun beating down like in the Sahara. You’re burning, you can’t go any farther. By the time we rowed out to the middle, where the BIG ONES were biting, we all realized we had to row back. We being ME. A-ha-ha-ha! I became Popeye Tallarico. Mowing the lower forty acres once a week gave me the shoulders to row back to shore (and to carry the weight of the world).

Up in the woods from the lake there were great granite boulders pushed there by glaciers during the Ice Age. There were caves up above the road I lived on in Sunapee with Indian markings on the walls—pictographs and signs. They were discovered when the town was settled back in the 1850s. The Pennacook Indians lived in those very caves. After killing off all the Indians, the whites built and named a seventy-five-room grand hotel after them, Indian Cave Lodge, the first of three grand hotels in the Sunapee area and the first place where I played drums with my dad’s band back in 1964—also just a half a mile away from where I first saw Brad Whitford play.

In the town of Sunapee Harbor there used to be a roller-skating rink. It had been an old barn; they opened up the door on the right side and the door on the left side and they poured cement around the outside of the barn so you could skate around the barn and through the middle out the other side. As a kid, it was a great little roller-skating rink. And back then, you could rent skates on the inside of the barn along the back wall and buy a soda pop, which they would put in cups that you could grab as you skated on by. Later on they put a little stage where a band could play behind where they rented the skates. By the next summer, not only could you roller-skate, but you could also rock ’n’ roller-skate to your favorite band. It was the first of its kind and it was called the Barn. Across the street was a restaurant called the Anchorage. You could pull your boat up and after a long day of waterskiing, sunbathing, or fishing-with-no-luck, get fish and chips. . . . And speaking of chips, no one made french fries better than one of the cooks that worked at the Anchorage—Joe fucking Perry. I went back there to shake his hand and there he stood in all his glory, horn-rimmed black glasses with white tape in the middle holding them together. He looked like Buddy Holly in an apron. I said, “Hi, how are ya?” or was it, “How high are ya?” At the time I was with a band called The Chain Reaction—and little did I know that my future lay somewhere between the french fries and the tape that held his glasses together.

At the end of each summer I’d go back to the Bronx, which was a 180-degree culture shock. A return to the total city—tenements, sidewalks—from total country—where the deer and the antelope rock ’n’ roam. Haven’t met many people who experienced that degree of transition. Where we lived was the equivalent of the projects: sirens, horns, garbage trucks, concrete jungle—versus the country—rotted-out Old Town canoe bottoms from the early 1900s, remnants from the last generation who once knew the original Indians. Holy shift! By September 1, all the tourists who made New Hampshire quiver and quake for a summer of fun had fled for the city from whence they came like migrating birds. Welcome to the season of wither. One was grass, green, and good old Mother Nature, and the other was cement sidewalks, subways, and switchblades. But somehow I still found a way to be a country boy, so even in the city I could be Mother Nature’s son—but with attitude.

Kids would ask me, “Where’d you go?” I’d tell them, “Sunapee!” Sunapee was a great mysterious Indian name. It was like coming from a different planet. When I got back to the city I would invent fantastic adventures for myself: escaping from a grizzly bear, attacked by Indians. “You’ve got a .22?” “You what?” And then I started the bullshit: “I got bit by a rattlesnake . . . ,” showing them a scar I got falling into the fireplace that summer. It was kind of like believing your own lie; you tell a lie and it grows. “The thing came at me, it was drooling, it had blood on its fangs from the camper it’d recently killed.” “You’re kidding me?” “No, seriously, it was rabid, but I nailed it right between the eyes with my .22.” Well, I didn’t want to say I was mowing lawns and taking garbage to the dump. That didn’t cut it with the girls, or the guys who wanted to beat you up if you didn’t represent a Bronx-type attitude. I wanted to talk about how I killed a grizzly with my bare hands—I was Huck Finn from Hell’s Kitchen. City people have bizarre ideas about the country anyway, so I could make up anything I liked and they’d believe me. Remember, this was 1956. And Ward Cleaver actually had a son, not a wife, named . . . Beaver.

I was about nine when we moved from the Bronx to Yonkers. I hated being called Steve. I was known as Little Stevie to my family and that’s cool because that’s my family. But being called Steve by anyone other than my family sucked. Getting moved from the Bronx to a place called Yonkers (a name almost as bad as Steve) took a little adjusting to. It was too white and Republican for a skinny-ass punk from the Bronx. My best friend’s name was Ignacio and he told me to use my middle name, which is Victor, a-lika my poppa! This suggestion, coming from a kid whose name sounds like an Italian sausage, was perfect. So for a year everyone called me Victor and that’s just how long that lasted.

At twelve, my first band . . . me, Ignacio, and Dennis Dunn. (Ernie Tallarico)

Moving from the Bronx to Yonkers was okay because we lived in a private house with a huge backyard and woods everywhere. There was a lake used as a reservoir two blocks from my house, where my friends and I fished our teenage years off. It was filled with frogs, salmon, perch, and every other kind of fish. There were skunks, snakes, rabbits, and deer in my backyard. There was so much wildlife in those woods that we all started trapping animals, skinning them, and selling their fur for pocket money, a kind of backwoods hobby I learned from the 4-H friends I grew up with in New Hampshire. When I was fifteen I found a toy store that sold wading pools for toddlers in the shape of a boat. I bought one and humped it down to the lake, paddled out and picked up all the lures that were caught in the weeds. I wound up selling them to the same people who had lost them to begin with. I was a reservoir dog before it was a movie.

At fourteen I found this pamphlet in the back of Boy’s Life or some other wildlife magazine, with an ad for Thompson’s Wild Animal Farm in Florida. You could buy anything from a panther to a cobra to a tarantula to a raccoon. A baby raccoon? Wow, I gotta have one! I sent away and it arrived in a wooden crate looking up at me with eyes like a Keane painting or a Japanese anime schoolgirl. I gave him a bath, threw him over my shoulder, and headed down to the lake. It was there that he taught me how to fish all over again. I named him Bandit because when you turned your back he would either pick your pockets or steal all the food out of the refrigerator. After a year of his ripping the house apart, I realized that a wild animal kept in the house is not the same as having a domestic animal as a pet, so I had to keep him in the backyard. You’ve got to just feed them and let them be wild. If you take them in, they adopt your personality—and at age sixteen, I was full of piss ’n’ vinegar, which is not what you want a wild animal to be. He ripped down every curtain my mom put up in the house. I loved Bandit and he changed my mind about killing animals. I wound up giving him away to a farmer in Maine where he grew to a ripe old age, huge and fat. Eventually chewing his way to freedom, he bit through an electric wire and burned down the barn. You can still see his face in Maine’s Most Wanted. Way to go, Bandit!

Back in the Bronx, the kids would assemble in the courtyard every morning at good ’ol P.S. 81. “All right, class, line up!” at 8:15 A.M. sharp. One morning when I was in third grade, there was a girl in the courtyard and I must have grabbed a broken lightbulb and chased her around—like any smart (ass) little boy looking for affection would do. This was my way of proving that there was more to adolescent courtship than snakes and snails and puppy dog tails.

Her mother went to the principal’s office. “If Steven Tallarico’s not thrown out of this school, I’m taking my daughter out! He chased my daughter with a LETHAL WEAPON (blah blah blah). He’s an animal!” I was already Peck’s Bad Boy, and this didn’t help. They brought my mom in. They wanted to send me to a school for wayward lads and lassies, who are known today as ADHD kids.

“What? Are you kidding?” my mother said to the principal. My mom was soooo for me. “You know what? I’m takin’ him out of this school. Fuck you!” She didn’t say that, but her EYES did. And she DID take me out. I moved on to the Hoffmann School, which was a private school in Riverdale hidden in the woods, oddly enough, by Carly Simon’s house. Unbeknownst to me, Carly also lived nearby in Riverdale. Thirty years later, when we did a concert toether on Martha’s Vineyard, she told me that she also went to the Hoffmann School.

I was excited about the Hoffmann School, but I get to the place and find out it’s full of “spaycial kids.” Kids that go “Fuck YOU!” in the middle of class, who have some Tourette-type syndrome and scream their lungs out. A little wilder than public school, I would say: kids sniffing the glue during art class and writing graffiti in the hallways . . . kids eating finger paint and everyone shooting spitballs with rubber bands at each other. WOW, my kind of place!

These were kids like me, hyper, acting-out kids—real brats! Not that I was that exactly. I just had too much Italian in me, the kind of Italian who, you know, is loud, opinionated, in-your-face, with no brakes. But I knew that if I totally let go, there was going to be fucking cause and effect and it would end with a ruler across my knuckles. Still, I’d do anything I could think of. I remember once combing my hair in the lunchroom with a fork! That time I got off easy; setting a fire in a trash can was a different story.

So that was the Bronx, still somewhat wild. On my way to the Hoffmann School I cut through a field, jumping over a stone wall. Over the river and through the woods. There was a cherry tree that was so thick and fat, the size of an elm tree, and when it bloomed it was like an explosion of pink and white petals, like a snowstorm. In summer it was loaded with cherries.

I’d go around behind the apartment buildings looking for stuff to get into. I found this big, beautiful pile of dirt, which later I realized was landfill from all the apartment buildings in that area. A ten-story mountain of dirt you had to climb as if you were scaling Mount Everest. A kid’s dream! To me that pile of dirt was a mountain—Mount Tallarico. “Let’s go climb the mountain,” I’d tell my friends. When you got to the top of it there was a whole acre of land with weeds and saplings—and praying mantis nests and all sorts of things that no one could get to. Of course I had to bring a praying mantis nest home. It looked like something from between my legs—all round, tight, wrinkly, and kinda figlike. I hid it in my top drawer because I thought it was so cool. I woke up two weeks later and my room was full of little baby praying mantises—thousands of them! They’d just infested the place, all over our bunk beds, blankets, pillows, on the walls, and . . . “Mom!”

We opened the windows, ran out, and closed the door. Needless to say, I slept on the living room couch for almost a week. When we finally went back in they were all gone.

On the top of that mountain was a small tunnel that I’d seen but never explored. One day I crawled in a few feet, but it was dark and musty so I didn’t go too far. The older I got, the farther I’d go. Finally one day I was crawling back in there and I said to my friend, “Hold my feet!” Because as a kid all you’ve got in your mind is that it’s the rabbit hole, which I didn’t want to know anything about at that age. Later on, I paid the Cheshire Cat a million dollars to be my roommate! How strange that after we moved in together, he almost cost me my life.

I was being really cautious, wriggling farther and farther in, shining a flashlight as I went, with my friend holding my feet. And what do I find there but an old M1 rifle that someone had used to hold up a liquor store around the corner from 5610 Netherland Avenue. So I took the rifle and walked through the streets to my building with it over my shoulder like General Patton. And I thought, “Wow, look what I got! I can’t wait to show my mother.” She eventually called the police and told them where I found it. I was written up in the paper the next day and I had my fifteen minutes of fame. Quite a change for the kid who was always getting in trouble. Okay, I became a hero while trying to make trouble, but still . . . a fabulous first.

Meanwhile, back at the raunchy, I mean the ranch (à la Spin and Marty) in Sunapee, Joe Perry lived on the lake just six miles from me, over in The Cove. It was, like, all our lives as kids, he was there and I was there and we never ran into each other. We did the same stuff. He swam all day and lived in the water—and the lake water’s fucking freezing—any more than half an hour and your lips were purple. I’d get out of the water and lie on my stomach in the sand at Dewey Beach, stretching my arms out like wings and pulling the hot sand up to my chest, trying to warm up like a lizard on a rock. I can only imagine what my heart must have been doing, going through the hypothermia shuffle.

Me, six years old, with my sister, Lynda, and cousin Laura at Dewey Beach. I look like my son, Taj. (Ernie Tallarico)

But it wasn’t all purely idyllic up in Sunapee—there was racism, and we were Italian. The Cavicchio family used to put on water-ski shows in the harbor. They brought the show from Florida. They were the only ones who knew how to perform the water-ski jump, ski barefoot, and pull seven girls behind the boat, girls who would climb on each other’s shoulders to make a human pyramid. Then one day they took the docks away at Dewey Beach to drive the Cavicchios off. An era was over. Now, no one could go to Dewey Beach and water-ski off the dock. My uncle Ernie, however, had a different plan. He knew that once anybody learned how to water-ski, it was more fun starting with your ass sitting on the dock instead of in the cold water. So he built a nine-by-nine-foot raft, put barrels underneath to keep it afloat and four chains on the corners that went down to four rocks that anchored it to the bottom to keep it in place. Whoever tore the dock down couldn’t stop us, because the raft was far enough offshore that it wasn’t in anyone’s way. But someone got pissed that we had gone against the grain. One dark night they decided to take fat from the Fryolators at one of the harbor restaurants and smear it all over the top of the raft. It became so greasy and smelly that no one could or would want to water-ski off it. How odd is it that the fat from the Fryolator that Joe Perry used to make my french fries was the same shmutz that caused the first oil slick on Lake Sunapee? It was a countrified version of the Exxon Valdez . . . only it tasted a bit better.

I would hitchhike from Trow-Rico down to Sunapee Harbor on Friday night and meet up with the guys in town. The thing to do was to find someone to buy us some beer; then we would play this game of jumping from boathouse to boathouse, just like roof jumping in New York, only in New Hampshire, on the lake. The rule was you weren’t allowed to touch land, and whoever made it to the farthest boathouse got the six-pack of Colt 45 and the girl that thought it was cool. Cheap thrills. The Anchorage Restaurant down at the harbor had three pinball machines that were lit up all night long, especially if Elyssa Jerett was there. Nick Jerett, her father, played clarinet in my dad’s band. She was the most beautiful girl in Sunapee—and she later married Joe Perry. But back at the Anchorage, she was going full tilt all night long—she was a Pinball Wizardess!

My cabin up in Trow-Rico was tiny. It had a double-decker bunk bed, one bureau, and one window that pulled down with a chain. I slept on the top bunk, and in the morning my father would wake me up by throwing apples from the crabapple tree. Around 7:00 A.M. If I’d gotten any sleep at all, it was rise and shine no matter what. He didn’t throw the apples hard, but it was loud enough to wake me up. The sound and the rhythm of the apples hitting the side of the cabin was a muffled kind of music to me, kind of like the backbeat of a snare drum—it always reminded me of how loud a snare should be in a track.

My cabin where Dad threw apples at me to wake me up. (Ernie Tallarico)

Dad knew I loved playing drums, so he offered me a job playing with his band three nights a week, all summer long. What his band played was kind of like the society music you hear in The Great Gatsby tradition. We played cha-chas, Viennese waltzes, fox trots, and show tunes from Broadway musicals, like “Summertime” from Porgy and Bess. I was mortified when girls my own age walked in, turned around, and walked out. I so wanted to go into a rockin’ version of “Wipeout” or “Louie Louie,” instead of a waltz from Louis XIV, or so it seemed. We’d set up in the grand ballroom of the Lodge, and from 7:30 to 10:00 P.M. we played four sets, each a half-hour long. I had to pull my long hair back, slick it down with pomade and butch wax, and put it in a ponytail. I looked like a fourteen-year-old Al Pacino in Scarface!

I got two or three summers of that under my belt, playing every night for two months with my dad. The audience was older, but now and then some folks would bring in their daughters; it was a family affair. And while I was playing one night this good-looking girl in a white dress came in with her parents. I watched her from behind the drums, eyeing her up and down and fantasizing as little boys do. Her mother would look on while her father, of course, had the first dance with his little cherub. How cute! She had to be fourteen—plump, pubescent perfection, flashing her big green eyes, and hair down to her waist. “Oh, my god,” I thought, and overcome with teenage lust, I let my hair down, though it made my dad very angry. I wanted to let my FREAK FLAG FLY! I’m sure that hearing the songs we were playing, if she weren’t with her parents, any girl in her right mind would have been gone in two seconds! I could see her thinking, “I’m so outta here!” . . . and so was I! The chase was on! During the break, Dad was in the bar with the band and I was drooling in the hallway, looking for the cherub in the white dress.

There was a guy named Pop Bevers who used to come and mow the fields when we got up to Trow-Rico in July. He chewed tobacco—big plug o’ Days Work. I’d sit and talk with him while he rolled his cigarettes and taught me how, too. I’d make my own cigarettes using corn silk. I’d put it on the stone wall, dry it out, roll it up in cigarette paper, and smoke it. Corn silk! I tried chewing tobacco once and got so sick I blew chunks all over my sister Lynda.

Lynda, 1967. Vargas, look out. . . . (Ernie Tallarico)

Then came the drinking years. All summer long my family would collect large quart bottles of Coke. My mom would save empty pop bottles, beer bottles, and wine jugs during the winter when we lived in the Bronx and Yonkers, and we’d bring cases of empty bottles up to Trow-Rico. At the end of the year, when the guests would leave, it would be apple season, and my entire family and I would go pick apples at an orchard and bring them to a place that pressed the fruit. We’d take the juice and put it into the bottles and keep them in the basement of Trow-Rico where they would turn into hard cider. One evening after a show at our barn (where we played every Saturday night), my cousin Auggie Mazella said, “C’mon, let’s go in the basement.” We grabbed a bottle and drank the whole thing out of the tin cups from our Army Navy surplus mess kits. The top of the kit became a frying pan in which you could cook your beans over a can of Sterno. It had a couple of plates, a cup, and silverware—the coolest thing.

The hard cider was strong stuff. We drank it just like we were drinking apple juice, and with no clue that we were getting hammered fast. I stumbled into the barn where the band was jamming and began to entertain the startled guests in an altered state, one to which I would soon become well accustomed. The glow shortly wore off. I felt queasy, staggered outside, fell flat on my torso, and woke up with a mouthful of yard. I crawled back to my cabin. Had I learned my lesson? Yes! But not in the way you’d think.

One night at the Soo Nipi Lodge my childhood ended. I went from sitting with Daddy in the bar, having a Coke and eating peanuts, headlong into the evil world of dope! I met some of the staff, the busboys who lived down in the bungalows. Went out there and somebody twisted up a joint. Now, back then, we’re talking 1961, a joint was thin. They were tiny. Pot was so illegal I didn’t want to know about it. Another night I went into town to see a band at the Barn and one of the guys rolled a joint in the bathroom. He goes, “Hey, you want to smoke this?” “Nope,” I said. “I don’t need that! I got enough problems.” Plus I’d seen Reefer Madness, so I passed it up, but then I got curious. I don’t know if was the smell or the romance, but eventually everything that I did was illegal, immoral, or fattening.

Shortly thereafter I started growing pot, hiding it from the family—as if they would ever know what it was. I thought if I put it right there in the field, knowing my luck someone would probably mow it down. So I went up to the power lines and planted some seeds, thinking that maybe that was far enough away. I figured I could just go up there and water the plants whenever necessary. But first off, I took a fish—a perch that I’d caught in the lake—chopped it up in little pieces, and put it on the stone wall so the summer heat would ferment it. After two weeks, flies are buzzing around it. It’s rotten, just stinky! I mulched it with dirt, put it in the ground, took my pot seed, and went up and watered it every day. Two months later, I have a freakish bonsai of a pot plant. It’s had plenty of fertilizer, but for some reason it wasn’t growing. The stems were hard like wood. What’s wrong? I wondered. Maybe it was because New Hampshire’s cold at night—that’s it! Wrong. Turns out they’d sprayed DDT or some pesticide under the power lines that stunted the plant’s growth. Hey, motherfuckers! I was pulling leaves off and smoking it and getting high anyway. But the plant only had seven leaves on it. Still, I loved getting high and being in the woods. I would trip and go up to the mountains and streams with Debbie Benson—she was my dream fuck when I was fifteen.

I’d get high smoking pot with my friends in my cabin. We’d lock the door, even though I never had to hide my pot smoking from my mom. I’d say, “Mom, you’re drinking! Why don’t you smoke pot instead?” I’d twist one up and say, “Ma, see what it smells like?” She never said, “Put that out!” mainly because Mom loved her five o’clock cocktail (or the contact high).

When I couldn’t get a ride from Trow-Rico down to the harbor—which is what, four miles?—I walked. In New Hampshire at night in the woods, it was so dark, you couldn’t see your hand in front of your face. All those terrifying stories I’d told to my friends back in the Bronx came teeming to life. Wolf packs! Black widow spiders! Silhouettes of the Boston Strangler! Blood-thirsty Indians! I knew there weren’t any Indian tribes left up at Sunapee. We—the white man—had wiped them out. But what about the ghosts of the Indians? They would be really pissed off, rabid with unquenchable bloodlust. Or else I was trippin’ on my mom’s homemade hard cider.

When clouds went over the moon the road got pitch black and I went, “Oh, shit!” I tapped my way with a stick like Blind Pew from Treasure Island. Really lonely . . . and scary. Yonkers and the Bronx were always lit up. You could hide in the snowbanks and when a car came around the corner you could grab on to the bumper and ski along behind it. But in Sunapee I almost had to crawl on my hands and knees to follow the white line down the middle of a dark country road. Later on I’d be back on my hands and knees following another kind of white line down a different dark road.

When I lived up there and September came and everybody was gone, I’d feel abandoned. Rough stuff when you’re young. I used to think, am I going to be that crotchety old fuck yelling at kids to get off of my lawn? No, that’s not me. I was the kid pissing on the lawn. You know, at this point in my life, I’m still in the woods. There’s still so much I’m not sure of, and I kinda like that. It’s the fear that drives us.

“Seasons of Wither” comes from the angst and loneliness of those nights when I was walking down that spooky road.

Fireflies dance in the heat of

Hound dogs that bay at the moon

My ship leaves in the midnight

Can’t say I’ll be back too soon

They awaken, far far away

Heat of my candle show me the way

Now something new entered my life, less scary in one way but in another, more terrifying since it involved girls—that was long before I figured women out. “Right, Steven. You never did figure them out, did you? Just became a rock star and that sort of solved the problem.” Ya think?

Anyway, my cousin Augie and I had talked these two girls into going camping overnight with us. Two girls, a tent, day-gives-way-to-night, booze. Oh, man, you never know what could happen with that scenario. We could get lucky. . . . We came to a beautiful, rolling hill. It looked so plush and soft at night: “Wow! Where are we?” “I don’t know, man, but let’s pitch the tent and, uh, heh-heh, y’know. . . .” We had a six-pack of beer, girls, what could be bad? I don’t think we were doing the wild thing, but definitely making out and getting drunk. I wish I’d had the evil mind back then that I have now—but when you’re a boy you’re mortally afraid of girls! Terrified!

We wake up in the morning to someone shouting, “Four! ” I will never forget that. We looked at each other. What does that mean? Four? Louder this time, and then a golf ball slams into the side of the tent. Oh, “Fore!” We’d pitched the tent on the third hole on the golf course. Naked and hungover, we grabbed our stuff and ran like hell.

When I was six or seven, I went to church and sang hymns. There was a table with candles on it, and I thought God lived under that table. I thought that through the power of song, God was there. It was the energy rolling through those hymns. When I first heard rock ’n’ roll—what did it do to me? God . . . before I had sex, it was sex! The first song that went directly into my bloodstream was “All for the Love of a Girl.”

Way before the Beatles and the Brit Invasion, when I was nine or ten, I got a little AM radio. But at night up in Sunapee, the wind howled and I couldn’t get the radio stations I wanted, so I ran a wire up to the top of the apple tree. It’s still there! And I picked up WOWO out of Fort Wayne, Indiana, and heard “All for the Love of a Girl.” It was the B-side of Johnny Horton’s “Battle of New Orleans.”

“All for the Love of a Girl” was a slow pick-and-strum love song with Johnny Horton, curling his lips around the lyrics, twanging each word as if it were a guitar string.

It was very basic, almost the archetypal love song. It’s kind of an every-love-song-ever-written ballad. It’s all there in four lines. Bliss! Heartbreak! Loneliness! Despair! I sat in the apple tree and lived every line of it. The only thing missing was my raging schooner—the likes of which you could pup a tent with.

When I heard the Everly Brothers’ “I Wonder If I Care as Much” and those double harmonies . . . I lost my breath! No one ever did that anguished teen love song better than the Everly Brothers. “Cathy’s Clown,” “Let It Be Me,” “So Sad (to Watch Good Love Go Bad),” “When Will I Be Loved?” Oh, man, those heartrending Appalachian harmonies! Those harmonic fifths! I mean, God lives in the fifths, and anyone who can sing harmonies like that . . . that’s as close to God as we’re gonna get short of a mother giving birth. Behold the act of Creation . . . divine and perfect.

If you have any doubts, try this: Take a deep breath and hold one note with somebody—a friend, your main squeeze, your parole officer: “Ahhh.” When two people hold the same note and one person goes slightly off that note you’ll hear an eerie vibration—it’s an unearthly sound. I think in those vibrations there exist very strong healing powers, not unlike the mysterious stuff the ancient shamans understood and used.

Now sing in fifths, one sing a C and the other a G. Then one of you goes off key . . . that’s dissonance. Fifths in muscal terms are first cousins and in those fifiths there’s a magical throb. If you close your eyes and you touch foreheads, you’ll feel a wild interplanetary vibration. It’s a little-known secret, but that’s how piano tuners tune a Steinway.

God and sound and sex and the electric world grid—it’s all connected. It’s pumping through your bloodstream. God is in the gaps between the synapses. Vibrating, pullulating, pulsating. That’s Eternity, baby.

The whole planet is singing its weird cosmic dirge. The rotation of the earth resonates a great, terrible rumbling, grumbling G-flat. You can actually hear the earth groan like Howlin’ Wolf. DNA and RNA chains have a specific resonance corresponding exactly to an octave tone of the earth’s rotation.

It all really is cosmic, man! Music of the fucking spheres! The third rock from the sun is one big megasonic piezoelectric circuit, humming, buzzing, drizzling with freak noise and harmony. The earth’s upper atmosphere is wailing for its baby in ear-piercing screeches, chirps, and whistles (where charged particles from the solar wind—the sun’s psychic pellets—collide with Mother Earth’s magnetic field). Earth blues! Maybe some shortwave-surfing extraterrestrial out there listening through his antenna will hear our cosmic moan.

You can just about guess that anything can—is gonna—happen, so long as we stay here on earth. In a Stratocaster, say, you use a pickup wrapped with a few thousand coils of copper wire to amplify the sound of the strings. The vibration of the nearby strings modulates the magnetic flux and the signal is fed into an amplifier, which intensifies that frequency—and blasts out into the arena. In the same way that you can take a note and amplify it, you could amplify the whole fucking planet. Planet Waves!

Take a compass. It’s just a needle floating on the surface of oil that’s not allowed to float freely. The power holding that needle is magnetism. The needle is quivering, picking up the slightest frequencies. Now, if you could amplify that . . . In thirty years, they’re gonna be able to do that, and I’ll have been sitting here going, “You know, there’s power in the needle of a compass and . . .” It’s actually a magnetic grid, the earth, so if you could amplify the magnetic frequencies of a guitar string, you could certainly amplify the magnetic frequencies of earth and beam it out there . . . Then you’d have the galactic blues blasted and Stratocasted out to the farthest planet in the cosmos.

Right outside my house in Sunapee there’s a big rock that my kids used to call “Sally.” It was their favorite thing to climb ’cause it was big and menacing and it drew them in. I had a special mystic boulder, too, but I never named my rock. It was right behind Poppa’s cabin. It’s probably thirty feet around and seven feet high, its surface so slick and smooth you can’t get a grip to climb it. But next to this rock was a tree, and using the tree I leveraged myself up and onto the top of the rock. I thought, “If I can get on this rock and stand where no other human has ever stood . . . I can communicate with aliens.” This raised some eyebrows among the other eight-year-olds on the playground.

When I scaled the boulder, my first thought was Holy shit, I’m on the top of the world! This is MY ROCK. Then I ran down to the basement of Trow-Rico, grabbed a fucking chisel—an inch around, six inches long—got a big ball-peen hammer—a really fat one that we used for chipping away stone to make stone walls—and I carved “ST” into that rock, so when the aliens come—and someday they are gonna come—they’ll see my marking and know that I was here and needed to make contact, and that I was one of the humans who wanted to live forever. That was my kid thought. I visited that rock recently, wet my finger, and rubbed it on the place where I’d carved my initials—and they were still there! I took some cigarette ash and put it in the S so I could take a photograph of it. E.T. meet S.T.

That was my childhood. I read too much. I fantasized too much. I lived in the “what-if?” When I read Kahlil Gibran I recognized the same alien shiver of wildness: And forget not that the earth delights to feel your bare feet and the winds long to play with your hair.

Trow-Rico went the way of my childhood . . . lost and gone forever, my darling Clementine. It stopped being a summer resort somewhere around 1985.

You can’t go home again; you go back and it’s not the same. It’s all crazy, small. Gives you vertigo, trying to go back. Like if you went to visit your mom, walked into the kitchen, and she had a different face.