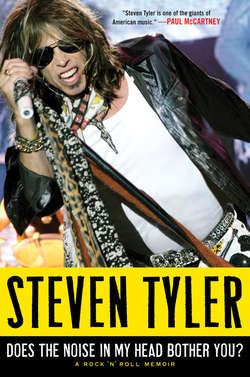

Читать книгу Does the Noise in My Head Bother You?: The Autobiography - Steven Tyler - Страница 8

ОглавлениеCHAPTER THREE

The Pipe That

Was Never Played

Before we get started, you’re probably asking yourself, “Is this about that famous pied piper from that children’s story or just another clever drug reference?” Read on . . . seek and ye shall find. . . .

I’m a great believer in moments arising. You’ll miss the boat, man, if you’re not ready for star time. Then at least you need a brother like the Kinks, Everly Brothers, and of course the Stones. And I was ready, ready as anybody could be. “Keith, gimme an E!” And the emcee is saying, “Let’s hear a big hand for old Whatsisname and the Miscellaneous Wankers.” Yeah, yeah, yeah . . . but I always thought I needed a brother to rock the world—and FATE would take care of the rest.

I’d been a rock star ever since I could remember. I came out of my mother’s womb screaming for more than nipple and nurture. I was born to strut and fret my hour upon the stage, fill stadiums, do massive amounts of drugs, sleep with three nubile groupies at a time . . . AND endorse my own brand of barbecue sauce (oh no, that’s Joe). All I needed was for the rest of the world to see who I truly was—Steven Tyler, the Demon of Screamin’, the Terror (or tenor) of tin pan time and space. Recipe demanded a cookin’ band, a few hit records, and, as alluded to a moment ago, my mutant twin. Was that too much to ask?

By the summer of 1970, sixties megalodons and heavy metal raptors still ruled the land—the Stones! The Who! Pink Floyd! Black Sabbath! Deep Purple! Led Zeppelin! All those poncey Brits with their bloody million-quid blues riffs, limey accents, Marshall amps, flaunting their foppish King’s Road clothes. We didn’t stand a chance, mate. Back in the USA little bands came and went. They huddled in the underbrush trampled by the passing Ledzeposaurs. If you heard a bustle in the hedgerow—that was us. I’d been in my share of these little bands, eking out a living gigging for sixty dollars a night (if we were lucky) in crummy clubs, gymnasiums, dance halls, and dives.

I was even the designated rock star of Sunapee (summer population, 5,400; winter population, 500). I had 45s on the jukebox at the Anchorage where we all hung out. I had a couple of singles out, the very pop and Brit Invasion–like ballad “When I Needed You” and the Beatlesque, Dave-Clark-Five-sounding “You Should Have Been Here Yesterday” with Chain Reaction. I was a local hero . . . a rapidly evolving legend in my own mind. But that was all. I’d burned through countless bands and come home a beaten child.

I started mowing lawns. I had a little piece of hash that I kept in my hash coffin and smoked in my hash pipe, which was labeled The Pipe That Was Never Played. A couple of tokes, get loaded in an old drafty house with little curtains that closed. I’d sit around with my friends. We’d talk about what we were going to do for a living. Maybe we’ll become cops—I actually said that! Oh, I swear! I wanted to be a local cop like my best pal, Rick Mastin, who carries a badge on the lake. I can drive around at night, I thought, at least have something to do, like Biff, the old cop in the harbor. What would we be doing when we’re sixty? That was another topic of conversation. Ah well, we’ll smoke cigars and sit on the deck. But as soon as the words came out of my mouth I heard a high-pitched bat shriek in my brain. No, I don’t think so.

Sunapee is not unlike Our Town—only smaller, a little more artificial (because it’s a vacation resort) and on a lake. Sunapee Harbor is just like the postcards of itself: quaint cottages, souvenir tchotchke shops, colorful local characters, aging rock stars. . . . The masts of sailboats sway in the harbor. It’s sooo picturesque. A perfect little stage set designed for tourists. Antique paddle-wheel boats docked next to an airbrushed little park. The crew wear Gilbert and Sullivan naval uniforms, and the captain narrates the cruise—the history, landmarks, and lore of crystal clear Lake Sunapee—as he indicates points of interest for the enlightenment and entertainment of the gawking visitors. “Now, over here, to your right, is the lighthouse where legend has it two star-crossed lovers would meet on moonlit nights . . . and over there is the summer home of degenerate rock star and control freak Steven Tyler [gasp!], who spent his summers here as a child mowing lawns and talking to elves. . . .”

They actually do an Our Town bit (billed as Crackerbarrel Chats) where old-timers (playing themselves) sit around an old woodstove at the Historical Society Museum and share, firsthand, their memories, experiences, and photos of days gone by. I’ve signed up for next year. My subjects will be whittling, bird-call clocks, the size of Slash’s cock, and how to throw a TV set out of a hotel window into a swimming pool so it explodes when it hits the water. (Hint: extension cords.)

Sunapee’s quaint all right, but if your aspiration in life is to be a rock star, then you’re in trouble. This isn’t the place to be. I knew that in a few weeks the town would start to close up. Like Brigadoon, every September it all evaporates. They fold up the flats, strike the set, and overnight it’s this deserted village—the kind of town you see in Stephen King movies where the place has been abandoned due to a supernatural fog. I’d stand in Sunapee Harbor all by myself and there’d be nobody there. It gave me the creeps! No wonder the town is filled with alcoholics—there’s nothing else to do.

Winters in Sunapee are brutal. Six months of howling wind and driving snow. A Siberian nightmare! And I’d spent plenty of winters in Sunapee, licking my wounds, getting high as a kite, brooding, regrouping, reassembling myself, and practicing my Jagger pout.

I’d spent too many winters up there doing that. I wasn’t going to do it again. I said, “That’s fucking it.” I prayed to the Angel of Cinder-Block Dressing Rooms and Ripped Naughahide Couches, “Deliver me from this horror!”

And then one day—like an apparition—Joe Perry! Joe pulled up to my parents’ place in Trow-Rico in his brown MG. There ought to be a plaque to mark the spot where that happened. God, I can see it in my mind’s eye—the pebble retaining wall below the big house, the steps up to the house where I used to clip the hedges—it was such a Technicolor wide-screen moment. He got out of his little Brit sports car. He was wearing black horn-rimmed specs.

“Hey, Steven, we have a band and it’s playing the Barn tonight. I wanted to invite you to come down and see us. You know Elyssa, right? She’ll be there.” Oh, yeah, I knew Elyssa, the pinball wizardess. She was Joe’s girlfriend, drop-dead gorgeous.

Now Joe, Tom Hamilton, and a little kid called Pudge Scott were in a group called the Jam Band that played around Sunapee and Boston. I went down to see them play that night at the Barn. There was Joe, Tom Hamilton on the bass, Pudge Scott on the drums, and a guy named John McGuire singing lead. All of them totally disheveled, fronting that unbridled bohemian cool of the early Brit rock bands. Joe looking a little dorky with his black-rimmed glasses patched with masking tape and his guitar way out of tune.

John McGuire was the original shoe-gazer . . . an affectation later taken to a high art form by Liam Gallagher of Oasis and others in the postgrunge bands of the nineties like Adam Duritz in Counting Crows. With these guys the lead singer looked down at his feet instead of out at the audience. Supposed to indicate authenticity, disdain for showbiz—but what the hell. I’m watching John McGuire looking down at his shoes and I’m thinking, God, no eye contact there, no connecting with the audience—what is that? Then I notice he isn’t exactly looking at the floorboards. He had a couple pages of Playboy taped to the floor of the stage between his feet, and he was looking down at her tits, you know—how great was that? Wonder if Eddie Vedder had pages of Surfer Magazine taped to those early Pearl Jam stages?

Joe sings lead on the next song. I’m sitting down with Elyssa watching Joe sing “I’m Going Home,” you know, the old Ten Years After song? Joe couldn’t sing at all. He sings like the Brit blues blokes, like Alvin Lee.Those kind of songs where you don’t have to hold a note (because you can’t actually sing), doing the early rock stutter, the way Ray Davies does “All Day and All of the Night.”

Next song. And then they went into “Weeeellll, beh-bee, if you gotta rock gong-gong-chick-gong, I got to be your rockin’ horse.” Joe’s singing it kind of like Dylan, because he couldn’t really hold notes back then—nor did he want to. Singing pretty, on key, was pop shit. Leave that to Dusty Springfield and Joannie Baez. The blues cats were aiming for the genuine Delta gris-gris growl.

They played only three songs the whole night—a lot of riffing, noodling—one of them being Fleetwood Mac’s “Rattlesnake Shake”—the mojo-driven Peter Green version (rough and dirty, pre–Stevie Nicks and the megahits). Fleetwood Mac’s Live at the BBC—we’d use that as our reset button. It’s the Holy Grail, the kabbalistic shit, pure unstepped-on melodic sensibility. Get that record, it’s all in there.

Joe couldn’t carry a tune to save his life and I thought, Oh, my god, these guys really suck! Oh, shit, these guys are so bad, they’re so out of fuckin’ tune, it’s embarrassing! I’ve got to get out of here!

They were playing this great Brit fret-burning blues, but they were horrible. They were out of tune, out of time—and I’m an animal of the beat, I have the ears of a bat. If a drum beat is a hundredth of a second off, I become unstable. I rant, I rave, it has to be fixed or the world will stop spinning on its axis. I drive my band crazy with this shit.

I was sitting there in the audience right next to Elyssa looking at Joe play. He had his Keith Richards moves down. The menacing hatchet-face scowl and bent knees as if the riff was so heavy it was weighing him down. The cool-chop look slightly undercut by his horn-rimmed glasses, white tape in the middle, hair down to his shoulders.

Goes into the second verse. . .

He do the shake

The rattlesnake shake

Man, do the shake

Yes, and jerk away the blues

Now, jerk it

Then—and this is the moment—Joe lurches into the guitar break: BOOAH DANG BOOAH DUM. Fuck! When I heard him play that, ah man, my dick went sooo hard! He blew my head off! I heard the angeltown sound, I saw the light. I was having that moment—the moment. Remember the scene in the movie The Miracle Worker about Helen Keller and her teacher? For a million years they’d done the hand signal thing. Then one day, out by the water pump, she signs W-A-T-E-R. At that moment, the levee broke.

Then he played the Yardbirds number “Train Kept a-Rollin’,” which became our top-this-motherfucker closer. Like me, an old Yardbirds fan—hence our mantras: “Train Kept a-Rollin’ ” and “I Ain’t Got You.”

My ear was a little more finely tuned than these guys’, but what I saw was this rough, raw, uncut rock ’n’ roll thing, the X-factor, the wild thang that runs through rock from Little Richard to Janis Joplin. Now that’s what was missing from the other bands. It’s not something you learn, it’s something you are. You play what you got. I’m thinking, with me make-believing rock star (which I could do so well) and Joe channeling Beck-Keit-Page, who could stop us? Who? They were in a very raw, rough state—but so what? If the horse doesn’t want to be ridden with a fucking bit in its mouth the whole time, what the fuck, let it go. If you’ve got this monstrous animal, let it run.

It was so fucking great it made me cry, and then the thought came into my mind just like the midnight train steaming into the station: What if I take what my daddy taught me, the melodic sensibility I’ve got, with the broken glass shards of reality that these guys wove together? We might have something.

Oh, yeah! When they did “Rattlesnake Shake” the fuckin’ energy coming off them was radioactive, they had the juice that all the bands I’d ever been in before couldn’t touch. The sacred fire! With all the acid and Tuinals and crystal meth, we couldn’t get to what they were doing on the natch. Right there what was beaming through was the white-hot core of Aerosmith. I went, “Ye-esss! YES!!!” I heard that high ecstatic voice, locusts were singing in my brain! And then I knew we’d have our day.

My whole life I’d been searching for my mutant twin—I wanted a brother. I didn’t want to be in another band without a brother. I needed a soul mate who would go “Amen!” Someone I could say “Fuck yeah!” to when I heard a million-dollar riff. In all the bands I’d been in from ’64 to ’70 there’d always been that one thing missing, the essential ingredient. Joe was the missing link. I wanted that Dave Davies–Ray Davies (that was real blood), Pete Townshend–Roger Daltrey, and of course, Mick-Keith thing. I’d never had that.

We’re polar twins. We’re total opposites. Joe is cool, Freon runs in his veins; I’m hot, hot-blooded Calabrese, a sulphur sun beast, shooting my mouth off. JOE’S A CREEP . . . I’M AN ASSHOLE. He’s the cowboy with the brim of his ten-gallon hat pulled down, the Hell-it-don’t-matter-none dude. But goddammit, is he always going to win? Am I always going to be the one with egg on my face? Of course, contrariness is the way the great duos have always thrived. Mutt and Jeff, Lucy and Desi, Tom and Jerry, Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis, Shem and Shaun, Batman and the Joker.

Right off, there was teeth-grinding competitive antagonism. The internal combustion engine that drives us. It’s in our DNA, part of our chemistry. The two-way thing going on . . . combination of the two. When I met Joe, I knew I’d found my other self, my demon brother . . . the schizo two-headed beast. Joe comes up with a great riff and immediately I think, “You fuck, I gotta top that motherfucker. I’m gonna write words that’ll burn up the page as soon as I lay them down!”

But you know what? Antagonism, pure nitro-charged agro, fuels inspiration. Do I have to explain these things to you? And you can’t control animosity, can you?

We’ve been chained together for almost forty years, on the lam, like Sidney Poitier and Tony Curtis in The Defiant Ones. Writing songs together, living next door to each other, touring, sharing girls, taping, getting high together, cleaning up together, splitting up . . . getting back together. There is a love there, no matter what. As soon as the anger gets resolved, we’re bosom buddies, nothing can ever drive us apart, but something inevitably comes up and I say, “Whoa! Wait a fuckin’ minute!”

Nobody can make me as crazy as Joe. No one drove me to the coffin for a reminder of the pied piper dream more often than Joe. Not ex-wives, not ex-managers—and you know how mad they can make me. Joe Perry is fucking Joe Perry—nothing I can do about that. Nothing I want to do about it. If he walked out onstage covered with vomit and shit and a needle hanging out of his arm, people would still applaud him and scream because he does the guitar god better than anyone. He’s the real deal. Not that the real deal is always the best deal.

Also the doomed, self-destructive rock star thing . . . straight out of the old Rock Star Handbook. Which is why I’ve got to keep my eye on him. Someone has to! Women love him; they have to live with his shit, his sniveling, smoking, and doping too much. I see him from the outside. Joe fucking Perry is the ultimate . . . but I’m the one who can see the shadow over, under . . . and inside him.

And there is a fucking Cloud of Doom passing over his head. My relationship with Joe is complex, competitive, fraught, really sort of fascinating in a hair-raising kind of way. There’s always going to be an undercurrent, ongoing tension, periods of homicidal hostility, backstabbing jealousy, and resentment. But hey, that’s the way the big machine works.

We’d joined that illustrious company of brawling blues brothers: Mick and Keith! Ray and Dave Davies! The Everly Brothers! That’s us, the Siamese fighting fish of rock! Awright! Bring it on.

But whatever happens, when we go on tour it fuses us together, we become the big two-headed beast. I see Joe every night and I go, fuck, that’s it, I get it! This is why we do it! And why I love it. Everything kind of washes away. All of that.

After that night, the Rattlesnake Shakedown, I was ready to make it happen. Tom and Joe were still in high school when I first met them, thinking about going to go to college. I had already burned my boats. I was never going back. I said to myself, Fuck it, I’m going to take a chance and move in with everybody.

Now, I knew we could do it. I loved sixties music; Brit rock stars were the shit. I wanted that sound so bad. And almost as much as I wanted the band, I wanted that lifestyle. I wanted it more than anything. I could taste it. The band was going to be the sixties Mach II . . . the Yardbirds on liquid nitrogen.

We’d all move to Boston and get down to the serious business of becoming famous. We had everything else, now all we needed was the fame to go with it. And being that I’m a little more crazed than most people, once I saw the light, I went for it hell for leather. My bags packed, at the end of that summer I said good-bye to my mom and dad, going, “Okay, here we go, this is the shit.”

The day we drove down—and here you have to stretch out the syllables—d-r-o-o-o-o-ve down to Boston from New Hampshire, I remember looking out the window at the trees and hills rolling by. I was feeling a little pensive (for me). I was a bit anxious about moving in with everybody; but at the same time I was ecstatic. It was a good anxiety, nervous and excited at the same time. And just then, the highway opened up—right at the junction, right at that spot on the highway where you see the skyline of Boston, and you go, “What!?” Because it suddenly goes from trees, woods, and crickets to cars flashing by and skyscrapers and apartment buildings. . . . Just at that moment, I went, “Oh, shit, the city!” I was sitting in the backseat. I grabbed a box of tissues from the back window of the car and asked if anyone had a pen and started to write on the bottom of the Kleenex box.

I’m in my bubble in the car. It’s like a projection booth where I’m screening our future on the windshield, a wide-screen movie of coming attractions—I can see it! Joe’s Les Paul gnawing through reality like a sonic shark, little pop tarts throwing their panties onstage, the high of fusing twenty thousand people into your own fantasy. The car’s moving (it’s also in the movie) . . . images and words colliding, generating a kind of spell of what I wanted to happen.

At the moment that I saw the Boston skyline, words began flooding into my head: Fuck, we gotta make it, no, break it, man, make it. We can’t break up, we gotta make it, break it, make it, you know, make it. And I began writing: “Make it, make it, make it, break it,” saying the words over and over to myself as I wrote them, like a prospector panning sand in a stream, back and forth and back and forth—water and sand, water and sand—until a little nugget emerges out of the sand. And there in the back of the car I thought to myself, What would I fuckin’ say to an audience? If we write songs, get up onstage, I’m gonna be looking the audience in the eye, and what am I gonna say? What would I want to say? I’m starting to pan for the gold: What do I say? What would I want to say? What’s cool to say? All those ideas were beginning to gell into one fuckin’ phrase. . . . Whoops, here we go!

Um . . . good evening, people, welcome to the show . . .

[First-person, me singing to the audience . . . ]

I got something here I want you all to know . . .

[The collective we, the band . . . ]

We’re rockin’ out, check our cool . . .

[Um, no, no, that’s no good, uh, talk about my feelings . . . ]

When life and people bring on primal screams,

You got to think of what it’s gonna take to make your dreams,

Make it . . .

Oh, fuck yeah! Now I’m scribbling like crazy on the Kleenex box.

You know that history repeats itself

But you just learned so by somebody else

You know you do, you gotta think the past

You gotta think of what it’s gonna take to make it last;

Make it, don’t break it!

Make it, don’t break it! Make it!

And there it was, first song, first record. Put that in your pipe. . . .