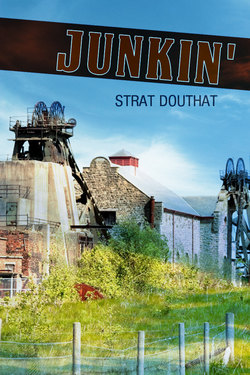

Читать книгу Junkin' - Strat Boone's Douthat - Страница 3

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ONE

ОглавлениеBenny Eskdale sat slouched behind the wheel of his battered green pickup truck sipping a warm Budweiser and watching heat waves dance above the Ford's hood ornament, a chrome-plated nymph that seemed to undulate in the shimmering heat. It was a steamy July morning and the truck’s cab was fast becoming an oven, even though Benny had parked in the shade. He took a last swallow and tossed the beer can onto the faded asphalt parking lot, then yawned and drifted sideways, letting gravity pull his body down onto the seat.

Gravity fascinated Benny and had ever since he was a little boy. Some of his earliest memories were of lying in bed at night, pondering the mysterious, invisible force that somehow kept everything in its proper place.

Sometimes he would worry that gravity might someday begin to lose its power. Would the earth become like the moon? Would people have to wear lead shoes? Would his family have to tie down their house in order to prevent it from floating away? Would his dog be safe?

Now, nearly three decades later, he was still intensely interested in the powerful effect gravity exerted on the physical world. And just now, he was especially aware of its heavy hand pressing down on his bladder.

“One thing. You can always depend on gravity,” he told the scarred dashboard as his shoulder hit the seat.

The impact sent up a swirling dust cloud, a miniature universe that slowly floated about the cab. A slanting shaft of sunlight ignited the swirling dust motes as they passed through it, transforming them into tiny, brilliant stars.

Benny was tracking a particularly bright star cluster when a voice suddenly thundered through the heavens.

“What's the matter, Benny? Passed out already? Hell, it ain't even noon yet.”

Benny blinked and sat up.

“Fuck you, Dwayne,” he said, rubbing his eyes with his fists. “As a matter of fact, I was busy creating the heavens and the earth. And if it wasn't for you, I'd probably be making Eve right about now.”

The little man stuck his grinning face in the window. “Just took a piss over by the bathhouse. There's a copperhead over there long as my arm, I swear.”

Benny snorted.

“It's probably just a blacksnake. Anyway, there wouldn't have been any snakes in my world. Well, snakes maybe, but no poisonous ones, least not in these parts.

“Dwayne, did you know it’s gravity that keeps the stars in place?”

“Dang it, Benny,” Dwayne said, “don’t you think I know a copperhead when I see one? He reached for the .22 automatic in the truck’s window rack.

Benny slapped his hand away and grabbed the rifle. “Show me that fucker,” he said, stepping out onto the parking lot, a weedy expanse of broken glass and discarded beer cans.

Dwayne aimed a smoke-stained finger at a beat-up cinder block building half hidden behind a festering mound of garbage bags and loose trash attended by a billowing cloud of swarming flies. “He’s next to the doorway. See that wet spot on the wall where I took a piss? He's a couple of feet to the right, just under that big lizard.”

“Fucker's after the lizard,” Benny said, hustling across the asphalt toward the gray, windowless structure, his eyes glued on the snake. He had gone only a few steps when his foot grazed a beer can, sending it skittering off to the side like a metallic mouse and spooking the snake, which darted toward the open doorway. Two shots splintered the door jamb an inch above the thick, sinuous body as it disappeared into the building.

“You missed him.”

“I know it, goddamnit.”

He edged up to the doorway and peered into the gloomy interior through the buzzing cloud of flies. The stench of rotting garbage was overwhelming and Benny pinched his nostrils in an effort to ward off the smell. There was no sign of the snake but he squeezed off another quick shot at a vague shape scurrying along a grimy ledge above some badly mildewed shower stalls, stalls he was all too familiar with, having stood in them on many an evening as the hot shower rinsed away the grime from yet another long shift deep below the towering hills hemming in the small mining complex he and his friends had been cannibalizing off and on for the past several weeks.

The shower nozzles were gone now, as were the wooden benches and the pulley-operated wire clothes baskets. Charlie's cap was still there, though. Benny could see it perched on a high rafter where he had tossed it one evening several years earlier. It was only a few days later that a rock the size of a watermelon had dropped from the mine roof onto Charlie, mashing his head so bad they'd kept the casket closed at his funeral.

He stared at the dusty cap, watching himself snatch it from Charlie's head and seeing Charlie's expression of disbelief upon realizing his beloved cap was out of reach.

They'd just finished working the evening shift and, as usual, Charlie was trying to get him to go down to Ida's Place instead of going home.

“C’mon, Benny,” he'd said, “you can always tell Ruth you had to work overtime. You tellin' me you're so pussy-whipped you're gonna go home and crawl into bed beside a snoring woman when we could be drinkin’ a cold beer and talking up some strange?”

Benny had gone down to Ida's that night. He’d had a good time, too, but there had been hell to pay the next morning.

Funny how things turn out, he thought as he stared at the dusty cap…Charlie's gone, just a bunch of bones now, and Ruth's in Ohio. Even Ida's Place is gone. Wonder if Charlie’s getting any strange, wherever…

“Hey, Benny!”

Dwayne pulled at his sleeve. “What'cha lookin’ at?”

Benny didn’t reply. He spun away as Dwayne peered over his shoulder into the dark, gutted interior.

“Phew! It smells worse around here than an outhouse,” Dwayne said, wrinkling his nose. “Jesus, you couldn't pay me to take a shower in there now, you know? I bet...”

“Goddamnit, Dwayne!” Benny jerked down the bill of his cap, the old blue one he always wore when he was junkin'. He turned and quickly strode back across the parking lot, leaning into each stride so that his powerful chest and shoulders ran interference for the rest of his body.

Reaching the truck, he climbed inside and put the rifle back on the rack, then sat scowling at the raggedy one-armed figure trotting toward him.

“You know something, Dwayne? You look like a goddamned scarecrow. The least you could do would be to get yourself a new shirt and some decent pants, even if you won’t wear your fake arm.”

Dwayne didn't say anything. He didn't even duck as Benny, grinning, reached out of the cab and grabbed his empty sleeve. He pulled Dwayne close and whispered, “How you ever gonna get a woman if you don't clean yourself up? I've seen you lookin' at those girlie magazines down at the Hut, you know.”

Dwayne reddened. “Hell, Benny I can't never get a look at them magazines cause you always got your nose in 'em.”

Benny laughed. “Damned right. I'd sure like to get my nose in some of that stuff.”

He relaxed his grip on Dwayne's arm, squinting up at the bright slice of sky above the hollow. “Ol' buddy, what say we do a little junkin' while we wait for Norvil and Junior to get back with the beer? It's gonna be too hot before long.”

He grabbed the acetylene torch and goggles from the truck bed. Dwayne selected a long, slender crowbar and they headed for a small brick building on the far side of the parking lot, Dwayne leaning on the crowbar as if it were a cane. The brick building had always been called “the pay office.” Officially, it was the southern West Virginia field office for The Blue Sulfur Coal Corp., a Cleveland-based outfit that had called the shots on Cabin Creek since the 1920s. But all that had ended abruptly the previous year when the company suddenly pulled up stakes and walked away, stranding the some 1,200 families who had depended on the mine for their daily bread.

“Hell, it’s too hot already,” Benny grumbled as they wove their way around the piles of debris.

He could feel the gravitational pull beneath him. His feet, small and narrow like a woman's, sank slightly into the soft asphalt and he almost tripped on a little metal stump when they reached the edge of the parking lot. The stump, and several others like it were all that remained of the chain link fence they'd hauled off to the junkyard the previous week.

Benny pulled on the goggles and pointed to a heavy metal door that had guarded the pay office entrance. The door now hung askew on one rusty hinge. “Let's do the door first, and then get the window bars.”

The torch sliced through the hinge, sending up a shower of white sparks. Benny stepped back and Dwayne yanked the door from its frame with the crowbar, jumping back as it came crashing down. They started across the threshold but stopped short as a foaming stream of termites erupted from the shattered door frame.

“Godamighty Benny! Lookit. There must be a million of them suckers.”

Benny stared at the pale, hairless creatures. Their blind, questing movements reminded him of something. Piglets! That’s what it was. They reminded him of the piglets he had watched being born that time his grandmother's old sow gave birth to a squirming mass of tiny, hairless creatures, 16 in all.

“Let's fry 'em,” Dwayne said, reaching for the torch.

Benny pushed him away. “Why would we want to kill 'em, Dwayne? Aren't they just doing a little junkin,' same as us?”

“Not by a long shot,” Dwayne said, kicking the door jamb. They're bugs. We're people; we have souls and go to heaven when we die. Bugs don't go to heaven.”

“How do you know where bugs go? Maybe they're in hell right now and you're the devil, you and that blowtorch.”

“Godamighty Benny, watch your mouth. Do you want to be struck down by lightning?”

Dwayne was still mumbling as they dragged the heavy door to the truck and heaved it onto the bed. He always had been deeply religious and had become even more so since losing his arm. He and Benny had been friends since grade school. Dwayne was a slight, sickly boy who had been bullied mercilessly until Benny took pity on him and became his protector. Dwayne had revered Benny ever since and looked up to him as an older brother even though Dwayne, in fact, was a few months older than Benny.

They sat on the tailgate. Benny rolled himself a cigarette, all the while staring at the mine office. The date “1923” was carved into the stone lintel above the empty doorframe.

He motioned toward the date. “Dwayne, wasn't that the year the coal company brought the armored train up the hollow and machine-gunned the strikers' camp? Marvin was just a little boy when it happened. He said he was all covered with splinters from where the bullets hit the trees above the tents. He said they sounded like rain on the tent.”

Benny reached down, picked up a rock as big as his fist and hurled it at the building.

Take that, you fuckers!” he yelled as the rock glanced off the roof. Even now it felt like an act of defiance, given the psychic residue of the enormous power once wielded by those far-away faceless men whose decisions and whims had for so long shaped the lives of the families living along Cabin Creek. He stared at the building through the smoke curls from his cigarette. It’s the temple of the gods of smoke, he thought. That’s it, they are the gods of smoke and now they’ve made everything go up in smoke, at least around here.

But the temple was defenseless now, its gates down.

“It's ripe for the picking,” Benny said as he stared at the empty doorway. He was just sorry there weren't any vestal virgins behind those brick walls, like the ones they’d read about in world history class. He was in the 11th grade at the time and had lain in bed at night imagining he was a Hun carrying off a temple maiden after sacking Rome or Constantinople or wherever it was. He and Charlie had exchanged knowing grins as Miss Dunfee told the class about the vestal virgins.

Just one little virgin would be enough right now, he thought; preferably, one with big, blue eyes and long, blonde hair. He envisioned the scene: him, Benny the Barbarian, crashing through the doorway; her, Vera the Virgin, cowering helplessly in a skimpy robe. She'd look up with pleading eyes as he reached down and grabbed her by that long, blonde hair.

He was just getting warmed up when Dwayne said, “I think it was earlier, around 1920? When they shot up the tents?”

“You could be right, Dwayne. Anyway, it's ancient history now.”

He leaned back on the truck bed and shut his eyes, remembering the first time he'd entered the pay office. He couldn't have been more than three or four at the time. The building had seemed so big back then. He was with his father and could still remember, clearly, how Marvin's pace slowed as they approached the metal door that now lay in the truck bed.

The mine complex was nestled in a natural amphitheater at the head of Cabin Creek in a hollow surrounded by steep hills covered with oak, poplar, hickory, sassafras, greenbriars and poison ivy. Deer, raccoons, foxes and an occasional bear roamed the upper reaches of those hills, whose rocky crests were crawling with rattlesnakes and copperheads. Benny was born in the Arnoldsville camp, some four miles down the hollow from the complex. Blue Sulfur was one of the earliest complexes on the creek and consisted of the brick office building, the miners’ bathhouse, a small repair shop, a large, tin-sided supply shed and an old shake tipple that looked like a 30-foot-tall version of a 1930s washing machine. The company had said it was going to replace the old tipple with a modern one but had never gotten around to it. They never will now, he thought. Probably not in my lifetime, anyway.

The mine’s main portal was carved into the hillside 40 yards behind the tipple. A weedy railroad track stretched between the portal and the tipple. From where he sat, Benny had a clear view of that dark opening - eight feet wide and little more than six feet high. In shadow now, it was just an inky smudge against the hillside.

Back when he was working in Number 6, Benny sometimes would imagine the portal was a whale's mouth and he was Jonah, about to be swallowed up. A cable was stretched across the entrance, bearing a warning sign that read: “Danger. Keep Out!” The sign had been put up the previous September, not long after Benny got a pink slip in his pay envelope. All it said was, “No. 6 Mine will be shut down until further notice.”

There was never an official explanation, but a story in the Charleston Gazette quoted the mine manager as saying the closing was due to “changing market conditions.”

Rumors had been floating around for weeks that a shutdown was coming. But nobody ever imagined it would be permanent. Nobody imagined the company would just close the door and walk away for good.

“Danger. Keep Out!”

They're not just shittin', Benny thought, envisioning the dark, narrow passageway that sloped back into the mountain before plunging straight down 200 hundred feet into a maze of low, dank tunnels stretching out for hundreds of yards in all directions. It was definitely a dangerous place. Dwayne had lost his arm down there. Charlie had lost his life, and so had lots of other men including Benny's maternal grandfather, James Carson Early. He was killed in a 1928 explosion that left a dozen widows and more than 20 fatherless children. It was just one of the periodic mine disasters that had ripped through Appalachia since 1900, terrible events that pretty much were accepted as the price of doing business in the coal industry. An example of the industry’s attitude had been made crystal clear in the early 1970s when, in the wake of the collapse of a poorly designed coal waste dam, which led to the deaths of more than 100 men, women and children, a coal company spokesman called the tragedy “an act of God” in an obvious and callus effort to shift the blame away from the company’s negligence and put it in the lap of the Almighty.

Yet, despite the danger, the dust and the darkness, Benny missed the job. Sure, he missed the big paychecks; but he also missed sitting around with the men in the lunch hole, trading sandwiches and shooting the shit. He especially missed the sense of urgency and purpose, the noisy machines, the banter of the section crews as they pulled together to meet their production quotas.

He even missed the occasional fights.

More often than not, the fights were about little or nothing, just a way of blowing off steam and releasing built-up tension. Sometimes, however, they were about women. Benny had had several fierce battles in the lunch hole and had the scars to prove it. And while some of those fights stemmed from actual transgressions, some were simply the result of his reputation as a ladies’ man. For a time, back in high school, everybody called him Butch Cassidy because of his faint resemblance to Paul Newman, even though Benny’s hair was dark and his eyes were hazel, while Newman had much lighter hair and famous blue eyes. Also, at 5-foot-11 and 190 pounds, Benny looked more like a linebacker than the wiry outlaw Newman portrayed in “Butch Cassidy and The Sundance Kid.”

Dwayne was still thinking about the mine war.

“I’m pretty sure it was 1920,” he said. “Can you imagine anybody just walking off and leaving a nice building like that?”

Benny shrugged. “Who knows? Maybe they'll come back someday. There's still plenty of coal left under these hills. The mine office is still in pretty good shape, too. But it won't be for long, not unless somebody does something about that washed-out corner.”

He pointed to a section of the foundation that was being undercut by a small runoff stream. The rivulet, now just a summer trickle, joined with several others further downstream to form Cabin Creek, a shallow, trash and rock-strewn stream that snaked some 12 miles down the hollow before emptying into the Kanawha River a few miles east of Charleston, the West Virginia state capital. The creek’s name harked back to the days when squatters' cabins dotted the lower part of the hollow.

That was before the coal companies arrived. After pushing out the squatters, the companies began building a series of small communities composed of rows of identical plank houses. The first coal camps went up a few years after the turn of the century and soon were occupied by a mixture of job-hungry Negroes who came from Virginia and were willing to risk their lives in the mines, and the impoverished eastern European immigrants who were arriving in droves and, like the first generation of free blacks, also were eager to provide the back-breaking stoop labor needed in those early mining operations. Recruiters would meet them at the docks in New York and Philadelphia and bring them straight to Cabin Creek, where they worked 12-hour shifts, six days a week.

It was an era when the coal seams were blasted with dynamite charges and then shoveled into small hopper cars pulled by mules. Safety was an afterthought and probably wouldn’t have been thought of at all except that explosions and roof falls tended to halt production and threaten profits. The mules and miners were expendable as there were always plenty more animals and immigrants available to go into the mines that were being sunk into the hills and hollows across the region.

Everything was automated by the time Benny entered the mines. The coal mined by his fellow workers was shaved from the seams by large, electric-powered machines that then pushed the coal onto conveyor belts that took it outside to the tipple, where the rocks and dirt were sifted out before the cleaned coal was loaded onto railroad hopper cars. Long gone were the shovel-wielding miners who had blasted the seams with dynamite and the mules that had transported the coal from the mine.

Initially, in the earliest days, the coal from Cabin Creek was put into bushel baskets and loaded onto barges bound for Cincinnati and other points downstream, via the Kanawha and Ohio rivers. It later was shipped out on the rail cars, with most of it going northward to fire the Pittsburgh steel mills or provide electricity for the growing industrial cities of the Northeast.

Sitting on the truck bed, Benny wasn’t thinking about those early days; instead, he was musing about the role gravity played in coal’s formation. After all, it was gravity that had pressed all those endless layers of rock and silt down onto the giant, prehistoric plants that, ever so slowly over eons, had been transformed, first into lignite and then into bituminous coal, known as “soft coal.”

West Virginia, which later broke away from Virginia in 1863, during the Civil War, was still part of The Commonwealth when it was first discovered that vast deposits of coal and natural gas lay beneath the region’s wild, heavily forested hills and hollows. The first commercial mining ventures began in the late 19th Century, some 20 years later, a time when the new state was still thinly populated. The early settlers of western Virginia were mainly poor Scotch-Irish immigrants who had begun drifting into the region in the early 1800s. Looked upon as ignorant heathens by the wealthy, slave-owning Tideland residents, these “hillbillies” lived off the land and supplemented their meat-heavy diets with edible wild plants and the few vegetables they were able to grow in the narrow, winding hollows. They also made corn whiskey and produced a crop of first-rate fiddlers.

The first miners were paid in company script, private money minted by the coal companies. Script could be redeemed only at the issuing company’s store, which also would give credit to the miners, many of whom wound up “owing their souls to the company store” as noted in Tennessee Ernie Ford’s popular song several decades later. Those men who sought better working conditions or disputed their credit account, often were fired and ejected from their company-owned homes, thus subjecting themselves and their families to the prospect of starvation in a one-industry region that offered few social services.

Benny stood up and stretched. “I'll bet that old building would last another 50 years if it wasn't for us termites and that runoff ditch,” he said, pulling Dwayne to his feet. “I've got my wind back now. Let's go look for those virgins.”

Dwayne gave him a funny look, but Benny clapped him on the shoulder and said, “C'mon, you hungry Hun, you.”

“Benny, sometimes I wonder about you, you know?”

The mine office was empty except for an overturned desk, a battered filing cabinet and a tarnished spittoon that had been squashed flat and now resembled a big, green frog. Dwayne looked into the scattered desk drawers. “Nothing here, 'cept a piece of script,” he said, holding up a perforated brass coin bearing the legend “Blue Sulfur.”

He handed the token to Benny, who was perched on a corner of the desk.

“I was just a little kid first time I ever saw this ol' payroll desk,” Benny said. “Marvin had come up to get his payday. I remember the payroll clerk wore a green eye shade that looked like a duck's bill. He would hand the pay slips out that window there. Marvin said the company store had overcharged us. There wasn't but about two dollars’ worth of script in his pay slip. He cussed all the way back down the hollow.”

Dwayne grinned. “Marvin can turn the air blue, that's for sure. Haven’t seen him for a while. He feelin' okay?”

Benny shrugged. “About the same. Still suckin' on that oxygen tank and smokin' one cigarette after another. He'll blow himself sky high someday, and more'n likely take Grandma with him.”

Dwayne cocked his head. “Car's comin'. Must be Norvil and Junior with the beer.”

Benny went to the door and looked out.

“That's not Junior,” he said. “Not unless he stole a new Buick.”

Dwayne grinned. “Wouldn't put it past him.”