Читать книгу Junkin' - Strat Boone's Douthat - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

SIX

ОглавлениеRussell had been driving for almost two hours and still hadn't gotten a handle on how things had gone so wrong up in the hollow.

Dumb motherfucker, he thought. The dumb motherfucker doesn't ever think about anybody but hisself.

He reached under the front seat and pulled out the snub-nosed .38 Special he kept in the car. I should of shot the asshole, he thought, imagining the look on Benny's face. He replayed the scene several times, shooting Benny in the balls and then between the eyes. He finally settled on a version in which Benny squealed and turned to run, but never got more than two feet, before Russell shot him in the ass, making him jump like a jack rabbit.

“A new asshole for the asshole,” he said aloud.

He was crossing the Ohio River at Huntington, leaving West Virginia, when he glanced into the rearview mirror and snorted derisively. There, behind him on the bridge was a big, gold and blue sign proclaiming: NEVAEH TSOMLA.

Almost Hell would be more like it, Russell thought, shoving the .38 back beneath the seat.

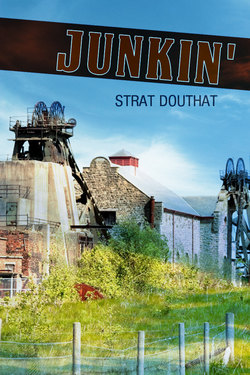

He drove westward on Route 52, paralleling the river. It was mid-afternoon when he reached Portsmouth, an old steel town 80 miles due south of Columbus. He stopped for gas and then drove on for a block before deciding to grab some lunch at a drive-in restaurant across from a sprawling, rusted steel mill. The mill had been closed for more than 20 years and the intricate maze of huge, rusted pipes gave its superstructure an orange hue, as if the plant had been painted with automobile primer.

Portsmouth, Russell knew, once had been a bustling place. It had even boasted a semipro football team back during the ‘20s and ‘30s, when the mill was going full blast. The Portsmouth Tanks, he thought it was. The team had played in an industrial league with other cities up and down the river, back before the start of the National Football League. Some of the league teams, like the Pittsburgh Steelers, went on to be part of the big leagues, but the Tanks had tanked as Portsmouth's economy cooled off.

He paused at the restaurant entrance and looked across the road at the mill. Its towering superstructure and stacks were crammed onto a narrow strip of land between the highway and the river. The rusting complex somehow reminded Russell of Cabin Creek, and he grinned as he thought of Benny's junking operation. That asshole Benny would love to get his hands on this place.

It was going on 4 o'clock when he paid his check. He decided call Ruth and leave a message on her answering machine, letting her know that he'd stop by later in the evening. Russell could hardly wait to tell her about finding Benny up there in the hollow.

Although he was only a year older than his cousin, Russell's prematurely gray hair and prominent paunch made him look almost old enough to be Benny's father. They'd never gotten along, especially when they were little and were vying for Grandma Early's favor.

“He always was a prick,” Russell told the dashboard as he turned the car northward, away from the broad river and began following Route 23 toward Columbus.

The highway was famous in the southern West Virginia coalfields, where high school kids said the three R’s really stood for “Reading, `Riting and Route 23.” In the years after World War II, when the coal companies were rapidly replacing miners with machines, hundreds of Appalachian families followed Route 23 to Columbus and other Midwest cities, looking for industrial jobs.

Russell was twenty minutes outside Portsmouth when he reached the village of Lucasville, a place that held nothing but miserable memories for him. He had spent five years in Lucasville after leaving Cabin Creek, working as a guard in the new maximum security prison built on a cornfield that had been owned by a local politician with connections in Columbus.

The prison was overcrowded from the beginning, and so dangerous that nearly a third of the inmates almost never left their cells, for fear of being assaulted or killed.

As he drove past the prison, Russell could make out the top of a glass-enclosed guard tower. The tower, its base obscured by the trees, seemed to float in the air, reminding Russell of a flying saucer.

It's for sure that most of those bastards belong in outer space, he thought, shuddering inwardly as he remembered what it was like being locked up with an army of killers and rapists who would as soon cut your throat as look at you.

The first couple of years were pure hell. Russell was assigned to the most violent cellblock, the “Kingdom of the Wild.” It was a place where an inmate might beat a man to death for a candy bar, or which TV channel they were going to watch. He had seen it happen.

It was the jack-off artists that bothered him most, however. Whenever a female guard was assigned to the monitor booth, the artists would whip out their tools and go to work, sitting directly in front of the monitor's window, where the guard had a clear view and vice versa. Russell couldn't believe his eyes the first time he saw it, but the other guard, a woman with two kids, didn't pay any attention. “I've seen a lot worse, and you will, too, if you stay here long enough,” she'd said.

Some of the female guards reportedly got off on it, at least that's what the hand-jobbers said. Russell had never gotten used to it, though. He was on the verge of quitting early in his second year, when he hooked up with Sinclair Smith, a black inmate with Columbus drug connections. Like Russell, Sinclair hailed from West Virginia. He was from Montgomery, just a few miles from Cabin Creek, and had hit the road when he was 15, after cutting a teacher who caught him selling shots of booze in the bathroom at Montgomery High School. He wound up in Columbus and became a small-time drug dealer.

But Sinclair was no longer small potatoes. In Lucasville he was known as the “speed king,” a man who could always be relied on to come up with bennies if you had cash or something else that interested him.

Sinclair and a few friends controlled the prison’s black drug scene. Their connection to the outside had broken down and Sinclair was looking for a new one when he found Russell. Within three years Russell had saved nearly $30,000. He used the money to open a small bar in Columbus, where he had made his own connections during his trips for the Sinclair Syndicate, as Sinclair liked to call his prison operation.

Wonder what ol' Sinclair’s doing this afternoon? Russell thought as he hit the gas pedal. Glancing over to his right, he saw the flying saucer dip slowly behind the trees.