Читать книгу Lord William Beresford, V.C., Some Memories of a Famous Sportsman, Soldier and Wit - Stuart Mrs. Menzies - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

CHAPTER I

EARLY DAYS

ОглавлениеTable of Contents

Early Childhood—Eton Days—Mischief and Whackings—Companions at Work and Play—Sporting Contemporaries of Note—The So-styled “Mad Marquis”—His Bride—Carriage Accident—Ride in Grand National—House of Commons Acknowledgment of Lady Waterford’s Goodness to the Irish during the Famine—Joins the 9th Lancers in Dublin—A Few Sporting Mishaps—Why he Spent his Life in India

The subject of these memories was the third son of the fourth Marquis of Waterford, who married the third daughter of Mr. Charles Powell Leslie of Glaslaugh, M.P. for Monaghan.

The children of this union were five sons:—

1. John Henry de la Poer.

2. Charles William de la Poer.

3. William Leslie de la Poer.

4. Marcus Talbot de la Poer.

5. Delaval James de la Poer.

In 1866 the fourth Marquis died, and was succeeded by John Henry, the first of the five sons mentioned already, and elder brother of the Lord William of whom I write. One of the most delightful characteristics of this family has always been its unity; the brothers were devoted to one another, their home and their parents. To the end of his days Lord William spoke of Curraghmore as “Home,” and of his devotion to his beautiful mother. She must have been a proud woman, having brought into the world five such splendid specimens of humanity, all handsome, having inherited the Beresford good looks, high spirits, and pluck, whilst happily imbued with the pride of race which is the making of great men.

There is nothing snobbish or vulgar in being proud of our ancestry, though it may seem so to those who are unacquainted with their own. Even savages have pride of race, and it has been so since the days of Virgil, and before that. Let us hope it will always be so. It is our birthright, which is well, for it helps men and women to keep straight, sorry to be the first to lower the standard or bring it into disrepute.

Look at the pride of race among the different tribes in the East how strong it is, their castes are profound and deep religions to them, their inherited pride of race, for which they willingly die, rather than suffer any real or imaginary indignity.

This instinct is still strongly marked in our present-day Gypsies, who are exceedingly exclusive and proud of their race, and they will tell with pride, if you know them well enough, that the reason they are, and will be ever more, accursed and hunted from place to place, is because a Gypsy forged the nails used in the Crucifixion.

The Lithuanian Gypsies say stealing has been permitted in their families by the crucified Jesus, because they, being present at the Crucifixion, stole one of the nails from the Cross, after which stealing was no longer a sin. This sounds irreverent, but they do not treat it lightly. The belief has been handed down to them, grown with them, and they seem sadly proud of their history, legend, or whatever it may be.

From an early age Lord William seems to have realised what was due to his family and his race, for with all his high spirits, even in the effervescence of youth, never once has anybody been able to say he brought discredit on his family.

The Beresfords have for generations been keen sportsmen, high-spirited, unspoilt, straightforward gentlemen; using the word in its old-fashioned full significance. Lord William was no exception to this rule, and it has not been given to many to be so universally popular. His worst enemy was himself, inasmuch as he habitually put more work into twenty-four hours than most people would consider a fair week’s allowance. From an early age he loved excitement, courting danger and adventure, resulting in most of the bones in his body having at one time or another some experiences, and I shall always think that but for the juggling tricks he played with his life he might still be with us, and the world the better for his cheeriness, generosity, and loyal friendship.

This is not a proper biography in the everyday acceptance of the term, it aspires to nothing so great. I have neither the competency to entitle me, nor the ambition to urge me to write a formal and stereotyped account of Lord William’s life, but only some memories, full of the little things that matter, small details that bring us closer to the character and introduce us to the personality of the man.

It is not as a soldier, it is not as a statesman that I claim applause for Lord William, though both may be owed, but for his thoroughness in whatever he undertook, his unfailing cheerfulness, his loyalty, energy, and marvellous pluck.

In his early days the principle of—“Whatsoever thy hand findeth to do, do it with all thy might,” must have been driven home, for whatever he undertook, that he certainly did with all his might; but his generosity and his kindliness of nature and his tact must have been born with him on July 20th, 1847, in the quaint little village of Mullaghbrach, in the north of Ireland, where his father was rector until he succeeded his brother, the third Marquess, in 1859. The early days of Lord William’s childhood were spent in this peaceful home with the usual accompaniment of nurses, followed by a German governess until he was considered old enough for further instruction, when the Rev. Dr. Renau’s Preparatory School at Bayford was chosen, the present Lord Methuen being there at the same time. After which, when eleven years old, that is in the year 1858, he was sent to Eton, first to the house of Mr. Hawtry, and then into Dr. Warre’s.

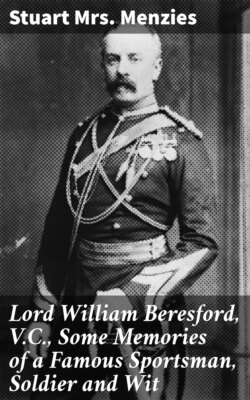

LORD WILLIAM AT ETON, AGED 11

It is interesting to note that the present-day actor is a relation of Mr. Hawtry of Eton fame. It was through the Eton Hawtry’s persuasions that the Prince Consort founded a prize for modern languages at the College.

Lord Cheylesmore, Sir Simon Lockhart, and Lord Langford were at Dr. Warre’s house with Lord William, the two latter being among the Doctor’s earliest pupils. Lord Langford says, “Bill was never out of rows of different sorts.” While Lord Methuen tells me he remembers seconding a boy named Allen at his tutor’s in a fight with Lord William, adding, “And it was a very hard fight,” but being senior to Lord Bill he saw very little of him while there. Dr. Warre-Cornish, Vice-Provost of Eton, said, “I always liked him. His Eton record is chiefly connected with schoolboy sports and skirmishes with masters at Windsor Fairs, and other places. He kept many bulldogs and was of a turbulent disposition.”

The gas works were close to Dr. Warre’s house, and behind them was the rendezvous of those who had any differences to settle. Lord Langford says, “I think Lord Bill often paid a visit there!” and adds, “On one occasion he captured a polecat and tied it to the leg of a chair in Dr. Warre’s house.” We can well imagine the breathless moments in store for the household. Various surreptitious journeys were taken to feed it and make sure of its safety. Then there was the exciting time of changing the animal’s quarters and attaching it, in spite of protestations, to a certain chair!

History does not relate what happened, but something entertaining, no doubt. After being a year at Eton, Lord Bill heard of the death of his uncle, and that henceforth his home would be at Curraghmore.

While at Eton he seems to have been chiefly conspicuous for his love of sport and fighting, his high spirits, ready wit, and popularity with all. He worked as much as was necessary and no more, for he loved the river, running after beagles, paper, or any other form of sport, more especially a fight. Happily in his time the battles were not so serious as they were in 1825 when Lord Shaftesbury’s brother, Francis Ashley, was carried home to die after fighting for two hours with a boy named Wood.

Like a few other men one could name who have been educated at public schools, and later held important and responsible posts, he could not always depend on his pen carrying out his wishes and spelling properly. Long after having arrived at years of discretion, shall I say? he constantly wrote to an old friend as “My dear Jhon,” meaning John. One day we were talking about certain clever people being unable to spell properly and chaffing him about it; nobody enjoyed a joke against himself better than he did. Somebody asked him, “Bill, why don’t you write the word you are uncertain of down on a piece of paper with all the variations as they occur to you? The look of the word would tell you which was right?” He replied, “I always do write it down on a piece of paper and never doubt its being right.” After which there was nothing more to be said, and we decided it would all be the same a hundred years hence, therefore it did not matter; and at any rate he had my sympathy. He agreed with Yeats, the Dublin poet, who sang:

“Accursed he who brings to light of day

The writings I have cast away;

But blessed he who stirs them not,

But lets the kind worms eat the lot.”

Certainly Lord William’s letters were short and sweet; he did not commit more to writing than he could help, thereby proving that he was a wise man.

Five years were spent at Eton, and they were spoken of as happy ones. Even at that early age his passion for racing betrayed itself and led to trouble, for on one occasion the attractions of Ascot became too much for him. Knowing that if he asked for leave to go it would be denied him, he took French leave, and received a whacking on his return, which reminds me that before Lord William’s time a certain flogging block belonging to the College disappeared one day, having been kidnapped by one of the Beresfords, the third Marquess, I think, when he was at Eton, and is now in evidence at Curraghmore, or was a few years ago. As far as I can gather there was no hue and cry after that interesting piece of furniture, and the next time there was any whacking to be done another block was found to be reigning in its stead; so presumably there was a supply kept in the store-room among the pickles and the jam.

Lord William’s contemporaries, besides those already mentioned, were the present Sir Hugh McCalmont, afterwards a brother officer and life-long friend, the late Lord Jersey, and the present Lord Minto. Lord William was fag to both the latter in succession, Mr. Charles Moore, another life-long friend, and, I believe, Lord Rossmore.

At the age of sixteen, Lord William left Eton and went to Bonn to study French and German under a tutor named Dr. Perry, others studying there at the same time being the Hon. Elliot and Alec Yorke, and the Hon. Eric Barrington, who tells me he was also with him at Eton, where “his principal reputation was that he and a friend of his had been subjected to more floggings within a certain time than had previously been recorded by anyone else.” Sir Eric says when he found Lord William at Bonn: “I was both surprised and delighted to find Bill Beresford there, not having hitherto associated him with foreign languages.” Some amusing accounts are given to me also of the Bonn days, where he says: “Our tutor had a peculiar way of accustoming us to the use of the German tongue, as, though we had a resident German tutor in the house, we were strictly forbidden to make any German acquaintances in the town, and were enjoined on our word of honour to talk German to each other during certain hours every day. A worse practice could hardly be imagined. Nevertheless, Bill undoubtedly acquired a certain facility in chattering, which he afterwards told me was most useful to him with the Dutch during the South African campaign.” Again speaking of Lord William he says: “His nature was exceedingly lovable, and he was very popular with his fellow pupils and tutors, whom, however, he took no pains to conciliate. During one altercation with his German tutor, the latter was heard to say, ‘Beresford, I loved you once, but I despise you now!’ which diverted us greatly at the time.”

From accounts of those times it appears that it was the habit of Dr. Perry to give a gala supper the night before breaking up for the holidays, at which all the instructors were present. On one of these occasions a certain student at the University who had been giving Lord William lessons in Latin, and who was much attached to him, made the following speech in English with a very strong German accent: “I have heard of Merry old England, but I have never heard of the Merry old Ireland. I wish to propose the toast of the Merry old Ireland and the Merry old Beresford.”

To amuse himself at Bonn, Lord William used to boat with his companions on the Rhine, and took special delight in the company of an English livery-stable keeper, who kept a certain number of riding horses of inferior calibre, with which he was intimately acquainted, riding being his favourite recreation.

I am afraid Lord William constantly broke Dr. Perry’s rules, and was frequently being sent away in consequence; but his mother, Lady Waterford, said she took no notice of the letters telling her of her son’s dismissal, as they were invariably followed by others recalling the sentence. Dr. Perry was really much attached to his unruly pupil, and his pupil had a very loyal feeling towards him, and was the means once of saving his life. Sir Eric Barrington tells me the story, and I feel I cannot do better than repeat it in his own words.

“Our Easter holidays were short and spent in expeditions to Switzerland or the Tyrol. In the spring of 1866 Dr. Perry took six of us to the latter. We were to walk across a pass with two guides, carrying our knapsacks. We walked for ten hours with very little food; the guides became exhausted and refused to go any further, but Dr. Perry was determined to reach the village we were making for. He misunderstood the directions of the guides and lost his way. We boys were exhausted also by this time, so stopped at a small hay-hut, where we resolved to stay the night. Dr. Perry went on in the dark, and attempted to descend the mountain-side alone. Beresford became uneasy about his safety, and went off to look for him. The rest of us settled down and went to sleep, when we heard Beresford shouting he had found Dr. Perry, but could not persuade him to return, as he had sighted the lights of the village in the distance. Still uneasy, Beresford started off again with a friend in the early hours of the morning to look for Dr. Perry and see if all was well. After some time he thought he heard a faint cry, and looking over the side of the mountain descried the object of his search some way down sitting astride an old tree stump, which had mercifully broken his fall, but still in a most perilous position, and trying to keep himself awake by digging his fingers into the decayed wood. From a cottage nearby, Beresford managed to get a rope, but it proved too short, so he set off for the village, where he found his companions and the guides had arrived. Though feeling thoroughly tired out and done up, he insisted on returning with the guides to show them where to find Dr. Perry, and to help in the rescue. He was released with difficulty and after some hard work.

“Dr. Perry always felt he owed his life to Beresford’s perseverance, and on that account was disposed to show leniency when his high spirits led him into mischief on future occasions.”

Bill’s main characteristics were courage and loyalty; it was impossible not to be warmly attached to him.

It having been decided that the Army was to be the profession of Lord Waterford’s third son, after leaving Dr. Perry, several other tutors were requisitioned to put the necessary finishing touches to his military education, after which he passed very creditably into the Army at the age of twenty, joining that popular regiment, the 9th Lancers, as a cornet in 1867.

They were a merry crowd in those days. Among Lord William’s boon companions in the regiment were the present Lord Rossmore, otherwise known as “Derry,” Captain Candy, “Sugar Candy,” Captain Clayton, “Dick,” the present Colonel Stewart Mackenzie, “The Smiler,” General Sir Hugh McCalmont, and the Hon. Charley Lascelles, who could do such wonderful things with horses owing to his good hands and sweet temper; and many more too numerous to mention, not a few of whom, like Captain Candy, Captain Clayton, and Mr. Lascelles, have moved on into another room, where their friends can no longer see them.

It is an interesting fact that all good sorts and popular men get nicknames attached to them, it being a sign of their value and the affection borne them by their comrades. Not often are selfish prigs called by nicknames, possibly they may be known behind their backs as “The Swine” or “The Prig,” or some other uncomplimentary epithet which can only be used sub-rosa, for who could so address them to their faces?

Among his friends, who were legion, Lord William was known as “Bill.” His brother, Lord Charles Beresford, is always called “Charlie” in the most affectionate way by even the crowd in the streets, who all love him and look upon him as their own.

Those were grand happy days when Lord William first joined the 9th. He and his young friends had the whole world before them, life and health then being a matter of no consequence, no consideration, for in the arrogance of youth who takes thought of the morrow? If only when people are young they could be persuaded to take a practical view of life and map out their days, not spending strength too freely, or trying nerves too highly, but keeping a little in reserve, something to draw upon. Uncontrolled spirits often lead to disaster early in life. The Irish are especially buoyant and their mad spirits infectious and lovable.

In later years Lord William often spoke of those early days, referring in affection or admiration to many of his sporting contemporaries, among whom were Mr. Garret Moore, who between ’67 and ’69 rode many winners in Ireland and elsewhere. (He died in 1908.) Roddy Owen, a great winner of races, especially in India and Canada up to 1885, after which he surprised people at home a little by winning the Grand National on Father O’Flynn in 1892, Sandown Grand Prize two years running and, if I remember rightly, the Grand Military on St. Cross. Poor “Roddy,” as everybody called him, died in Egypt on active service in 1896, mourned and regretted by everyone who knew him.

Colonel Meysey Thompson, who had known Captain Owen all his life, wrote some charming lines “In Memoriam” when he died. I do not remember them all, at any rate not correctly, but one verse I know ran:

“May the date palm’s stately branches

Above thee gently wave;

May the mimosa’s scented wattles

Bedeck with gold thy grave.”

But as I am not writing Roddy Owen’s life I must hurry on, especially as poking into the pigeon-holes of the past is apt to bring on fits of the blues.

Captain Bay Middleton, another great friend, however, must not be forgotten. He was fond of cricket as well as hunting and horses. A member of the Zingari, Captained by Sir Gerard Leigh, and while in Ireland they played the 9th Lancers. I do not remember who won, but when the game was over Lord William, to amuse his friends, suggested a run with the drag hounds, managing to find mounts for all; they rode just as they were, in flannels. Needless to say the fun and enjoyment were great.

It was delightful to hear these boon companions living over again some of these times amidst happy laughter and friendly recriminations, though perhaps sometimes tinged with regrets for the days that were gone. Captain Middleton died in 1892, so another old friend passed out of Lord William’s life. It was in April, I think, when Captain Middleton was riding at quite a small fence (as is so often the case), that his horse pecked, throwing its rider forward, and, as almost invariably occurs when a horse is in trouble, threw up its head, trying to recover itself, and in so doing broke Captain Middleton’s neck. He was no doubt a great man on a horse, and as a rule they went kindly with him, but I have seen him at times by no means gentle with them, I am sorry to say, and not always when the horse was to blame.

Another great friend I must not pass over was Captain Beasley, called “Tommy” by Lord William, who rode in twelve Grand Nationals. I have only mentioned a few of the names that recur to me; it would take many volumes if I were to enumerate all his great friends, for few men had so many.

At any rate the fun in those days was certainly fast and furious, some of the practical jokes being distinctly drastic though considered very amusing at the time. I doubt if in these days they would be considered jokes at all. It does not follow that what was considered funny and witty by one generation will be considered the least amusing by the next, any more than what was true yesterday need be true to-day, and often is not.

On one occasion when his friend, Captain McCalmont, was driving him from Cahir Barracks to Clonmel, while passing through the town of Cahir, Lord William asked if he would mind pulling up for him to do some shopping. When he returned with his purchases they consisted of a sack of potatoes; this was planted at his feet, and as they continued their drive he amused himself by throwing potatoes at everyone they met. Some smiled and seemed pleased with the delicate attention and gift of potatoes, others, however, were not, therefore a crowd soon gathered and embarked on reprisals. The potatoes were coming to an end, but his blood being up, he purchased more and continued the battle. As they proceeded along the ten miles to Clonmel, news of the battle had evidently travelled ahead of them, for in places they found people waiting for them armed with missiles, including brickbats. It now became a question how they were to get away themselves. However, the Irish understand one another, and all the country was fond of the Beresfords, from whom they had received many considerations and benefits. At that time, in the eyes of the people, the Beresfords could do no wrong, so it ended, I am told, quite happily. In the autumn of our days it seems a very long time since we were so full of beans that we could do such mad things, the result of animal spirits.

Lord William’s uncle, the third Marquis, has been called the “Mad Marquis” owing to the extraordinary things he did, probably from the same overflow of spirits from which Lord William suffered when throwing potatoes at peaceful pedestrians on the road.

The so-called “Mad” Marquis certainly did some very astonishing things, but purely, in my opinion, from devil-me-care fun and spirits, for when married to the beautiful Louisa, daughter of Lord Stuart de Rothsey, whom he passionately loved, he settled down after sowing his wild oats, and became a model husband and landlord, beloved by the whole countryside.

It appears to be rather fashionable to think everyone is mad whom we do not understand, or even perhaps when they are superior to ourselves in courage or intellect.

I leave it to my readers to decide if he earned the sobriquet, if they think a man who was so exceedingly devoted and tender to his wife, and so full of consideration for his countrymen, could be rightly termed the “Mad Marquis.”

When he brought home his bride to Curraghmore, seeing a crowd of country folk and tenants collected to greet them, he leaned over his wife and lifted her veil so that all might admire, so great was his pride in her.

Soon after their marriage, when driving his wife, one of the horses became restive while descending a steep hill. The only thing to be done to avoid a bad accident was to turn the horses into a hedge at the side of the road. Lady Waterford tried to get out, and in so doing fell, hurting her head, causing concussion of the brain. Her devoted and alarmed husband carried his unconscious wife in his arms down the hill, through the River Clode, back to the house, that being the shortest way, so that she could be properly attended to more quickly. For several days and nights he scarcely left her; it was hardly possible to persuade him to come away even for food; and when the doctor said all her beautiful hair, that he admired so much, must be cut off, he would allow no hands to do it but his own.

CURRAGHMORE

Like all the Beresfords, the third Marquis was handsome and loved sport in every form, especially fox-hunting; he hunted the Curraghmore entirely at his own expense. It was a sad day when his mount, May-boy, made a mistake over a rotten wall, which put an end to all his hunting.

It must have been from this uncle that Lord William inherited his love for steeplechasing, for we hear of the Marquis in 1840, when it was first becoming the fashion for gentlemen to ride in chases, riding in the Grand National. He died in 1859 without any children, and was succeeded by his brother, Lord William’s father, as fourth Marquis.

In 1847 (the year Lord William was born) Lord and Lady Waterford devoted most of their time and much money in endeavouring to relieve the distress in Ireland caused by the famine. The Marquis imported shiploads of wheat for the people, and Lady Waterford’s goodness was so great that the House of Commons felt constrained to acknowledge it.

In return for this, these excitable people in the following year, under the influence of agitators, became so rebellious to law, and order and to their best friends, that Curraghmore had to be fortified against them. The Fenians declared they would capture Lady Waterford and carry her away to the hills.

This alarmed her husband so greatly that he took her to her mother, in England, for safety, returning himself to Ireland to protect the home he loved so dearly, and if possible save the people from themselves.

To return to Lord William. The 9th Lancers were stationed at Island Bridge Barracks, Dublin, when first he joined, which for an Irishman was all that could be desired. Then on from Dublin to Cahir, which is not very far from Waterford and Curraghmore; a troop of the 9th were quartered at Waterford and half a troop at Carrick-on-Suir, close to Curraghmore. For a time Lord William was with the Waterford troop, and it was a curious turn of fortune’s wheel that brought H.M.S. Research to Waterford harbour at this time with Lord Charles as a middy, or at any rate a very junior officer. Lord Marcus, in the 7th Hussars, was also at home on leave, so the brothers were together and there was a very happy gathering.

All the officers of the 9th and the Research were constantly at Curraghmore, where they were always sure of a welcome, many carrying away with them into foreign lands an affectionate gratitude for Lady Waterford, who had made a home for them all when in the neighbourhood.

9TH LANCERS IN DUBLIN, 1867

Back row, from left to right: Lieut.-Surg. Longman, Riding Master Crowdy, Capt. F. Gregory (A.D.C. to Lord Lieut. of Ireland), Capt. Cave, Capt. Hardy, Lieut. Gaskell, Cornet Stewart-Mackenzie.

Second row: Cornet Willoughby, Cornet Lord Wm. Beresford, Paymaster Mahon, Lieut.-Col. Johnson, Capt. Erskine, Lieut. Palairet, Lieut. Green, Cornet Percy, Adj.; Quarter-Master Seggie, Major Rich in plain clothes.

The 9th Lancers had a pack of harriers when at Cahir, Lord William acting as one of the whips. He had begun riding as a very small boy, on a pony called The Mouse, which was shared by the three brothers, each taking it in turn to ride. From this humble little mount he was promoted to other ponies, on which he soon began to execute little jumps, and ride about the country during the holidays. Before many years had passed over his head he became a follower of the Curraghmore hounds and other surrounding packs, often seeing more of the fun on his pony than some of the field on famous horses, partly owing to the plucky way he “shoved along” and to knowing the country well, also partly to the happy way ponies have of turning up unexpectedly and accomplishing wonderful feats by scrambling and crawling along places where bigger horses cannot find foothold. The old Curraghmore, now the Waterford, hunted a country of about thirty miles from east to west, and twenty miles from north to south, its boundaries being Tipperary, Kilkenny, and Wexford, and the sea on the south. Having thus graduated in horsemanship, by the time he joined the 9th he was known as a good man on a horse.

He naturally loved horses and dogs, and had many, being a good judge of both. In consequence of the number of the latter he usually had about him, Captain Fife, of the same regiment, when compiling an alphabetical list of rhymes in connection with his brother officers, on coming to the letter B, wrote:—

“‘B’ stands for Bill,

Many cur dogs are his,

Good-tempered but hasty,

And easily ris’”;

which, must be admitted, is a magnificent effort, even if it does not scan very well.

Witnesses of the fun in those days say they can never forget the delightful time when all the brothers were at home together. Each a sportsman, each a wit, full of merriment and pranks, and all especially delighted when Lord Charles danced a hornpipe for their amusement. How Curraghmore must have ached for their voices when they had, as the old song says, “all dispersed and wandered far away.”

It was when stationed at Cahir that Lord William began crumpling up his bones owing to various tosses of sorts. At this time he owned a very fast trotter, which could do sixteen miles an hour when requested. He started one night with this fast trotter in a dogcart to cover the three miles from the barracks to the station, taking an English guest with him to catch the 10.30 train for Dublin. The road was very dark and overshadowed by the trees of Cahir Abbey Park. Sir Hugh McCalmont (then Captain McCalmont), a brother officer already mentioned, was likewise performing the same journey bound for Dublin; both started at the same time. Lord William set the pace, and was soon out of sight and hearing. Added to the darkness, it was pouring with rain. After journeying some little way Captain McCalmont was held up by cries issuing from the gloom. Someone was shouting. He pulled up in time to find his friend with his guest, his fast trotter and some dogcart about the road. Lord William in his haste, combined with the darkness, had driven at top speed into a cart, somewhat to the surprise of the driver. The cart also looked as if taken by surprise, in places. Having satisfied himself that no one was killed, though all were more or less damaged, Captain McCalmont continued with his “crawler,” as he called it, to the station and caught his train, which is more than the fast trotting party did.

Trifles of this kind, however, never worried Lord William, for his spirits were unquenchable.

One of the fastest runs with hounds he could remember, in those days of scanty judgment, was when out with the Curraghmore hounds in the northern part of the country. The fences were not very big, but the pace was great. Lord William and Captain McCalmont were riding a bit jealous, I think; after racing for about twenty minutes, they both tried to fly a bank, with the natural result when jumping blown horses. Captain McCalmont’s gallant little mare did not get up for some time; she wisely lay still to recover her wind, but Lord William had been so struck by her performance that he shouted, “I will buy her”—and he did. But horses when asked to do too much, sometimes break their hearts, and the mare was never quite the same again.

Whenever sport was to be knocked out of anyone or anything Lord William was sure to be there. Nothing came amiss to him, fisticuffs, American cock-fighting, hunting, racing, polo, the latter only just becoming popular in England.

It was about this time that he came into his share of the family fortune. He considered it so inadequate to his needs, that he decided to spend the capital as interest. This is how he described it to me one evening, years later, in the grounds of the Taj at Agra.

“So inadequate to my needs was the interest on my share, that I decided to use my capital as income so long as it would last, and rearrange my life again when it came to an end. I started a coach, a stud of hunters, some racehorses, and laid myself out for a real good time. I managed to hold on until just before the regiment was ordered to India. Then, as the fateful day drew near, I thought I would have one final flutter at the Raleigh Club. A turn up of three cards at £1000 a card! I won the lot, was able to pay up all I owed and clear out to India, cleaned out, but a free man as to debt.”

I do not feel I am betraying any confidence, as he told the story to several people, and really it is an amazing example of what pluck and daring, combined with determination, can do. A lesson in resource and audacity that a young subaltern should arrive in India a penniless soldier, and yet reach the height of social and official fame combined with pecuniary comfort, as he did, in a few years. To sit down with premeditation and map out such a wild scheme, and then be able to bring it off and win the odd trick, was rather wonderful.

Possibly what he suffered during those years when he was riding for a fall made him reckless, risking his life more frequently than he otherwise would have done, thinking it was bound to be a short and merry one, so what matter? Or, like others I have known when riding for a fall, would not give himself time to think.

Some of the extraordinarily kind things I have known him do for young men when in financial difficulties, though not overburdened with cash himself at the time, leads me to the belief that he remembered his feelings when the crash of his own arranging was drawing near, assisted perhaps by a little luck, which saved him.

Considering that he was not a rich man, it was wonderful how lavish was his unselfish and large-hearted generosity. I verily believe no living soul ever went to him in trouble and was sent “empty away.” Yet he could never bear his left hand to know what his right hand was doing. It really ruffled him if he ever heard of it again. Nevertheless, some of those near his left hand did know what his right was doing, more often perhaps than he guessed.

Having explained the rather important financial position at this time, we can return to the daily happenings, able to see some reason in much that would otherwise seem of little consequence, but which meant a good deal to Lord William, we can also admire more sincerely the brain that evolved the scheme and carried it out.

Some will no doubt think, and possibly say, that the affection we all had for Lord William has made me picture a faultless man; this is, of course, not so, and it is not difficult to recognise his failings, which he shared in common with the rest of mankind, but I do claim for him that they were none of them mean, little, or contemptible, and we do not always like people less on account of their faults. Generosity may be called foolishness: pluck, foolhardiness: morals, not such as would be considered a proper rudimentary system for teaching in elementary schools: but if, after all that has been said, a man can count hundreds of deeply attached friends, and not one can say he ever did a dishonourable action, or willingly hurt another’s feelings, I claim that man is great.

Lord William was an admirer of beauty and good taste; add to this, as the cookery books say, his particularly charming manner, that would woo the birds off the trees, and his good looks, it is small wonder he was much loved by the fair sex.