Читать книгу Lord William Beresford, V.C., Some Memories of a Famous Sportsman, Soldier and Wit - Stuart Mrs. Menzies - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

CHAPTER III

JOINS VICEROY’S STAFF

ОглавлениеTable of Contents

What he Might Have Been—A Happy Exile—Lumtiddy Hall—Unsuccessful Journey to Pay Calls—Appointed to Staff of Retiring Viceroy—First Summer at Simla—Appointed A.D.C. to Lord Lytton—Annandale Racecourse—Birth of The Asian—Dinner to Its Sporting Owner—Winner of Viceroy’s Cup—Delhi Durbar, 1887—Mighty Preparations—A Terrible Accident

It is easy to imagine with what mingled feelings Lord William left England: relief at being freed from the money difficulties that oppress a young man in a swagger regiment in this expensive old country; affectionate regret for the splendid days that were done; the happy family gatherings, before all were scattered; still cherishing some of the ideals of youth to which there is always a sacredness attached. Children usually build mental universes round themselves, and at the age of twenty-eight hope has not died in the heart; that child of happiness still keeps it warm. Lord William, not being one of those who wear their heart on their sleeve, was of the merriest on board ship, full of courage and good resolutions, determined to map out his future on safer grounds than hitherto.

I have often heard it remarked that Lord William might have gained and filled almost any great position in life that he chose, owing to his talents, perseverance, and charm of manner, if it had not been that he was obsessed by his passion for racing and horse-flesh. It is said “he might have been a great soldier”; my reply is, he was. Again: “He might have been a great statesman.” I reply, that in a measure he was. To be the right-hand man of and Military Secretary to three successive Viceroys, and a capable A.D.C. to three, speaks for itself. What more could he desire, unless it was to be Viceroy? which would not have appealed to him in the least. Some of his friends have said they regretted his not having entered the Diplomatic Service, which shows how little they understood him, for nothing could have been less attractive to him, or more foreign to his nature, than a life of trying to make black look white; though an adept at bamboozling people for their own advantage, and smoothing rough corners for their happiness, to bamboozle them to their detriment, and smile with the face of a truthful prophet while so doing, would have been impossible to him; also he was much too loyal for that profession, who proverbially, as a class, are not given to standing by one another. Any question that he had to decide he would gladly have done with his fists, or sword, but not by parliamentary inexactitudes. Besides, who among those who knew him would have liked to see him any different from what he was?

India appealed to Lord William, he liked it from the first. Perhaps he, more than some, felt the loneliness inseparable from landing in a strange country for the first time, with a career to make out of nothing; far from the help and glamour of home associations, feeling rather like goods on a market stall, from which the ticket describing their merit and value has fallen, leaving the said goods to prove their own merit, and so create their own price.

Starting a life in any new country, individuals are only a number to begin with. Yet India is one of the kindest to strangers, there is something in the atmosphere that melts the Northern “stand-off” attitude. All are exiles, which forms a bond of sympathy, uniting them into one big family, so to speak. It is good for all to find their own level; travelling assists them, gives them a new education. There is much to be learned in a large mixed cosmopolitan concentration, where princes, rajahs, judges, generals, police, subalterns who know everything, old men who believe nothing, middle-aged men who suspect everything, all rub shoulders, look well groomed and comfortable, yet all with the same longing for home in their hearts.

At Bombay, Lord William met his brother, Lord Charles, then in attendance on the Prince of Wales; this meeting was a great pleasure and took the chill off the landing.

Sialkôte is a pleasant station, more shady than many, boasting fine trees and a certain amount of vegetation. A charming bungalow was secured and shared by Captain Clayton and Lord William. These stable companions were greatly attached to one another; the former had a good influence over his wild-spirited friend, who quite recognised and appreciated the fact.

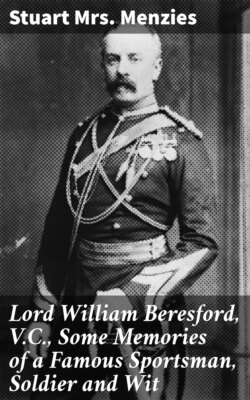

LORD WILLIAM BERESFORD AND CAPTAIN CLAYTON

The bungalow was christened “Lumtiddy Hall.” In the photograph the tenants are seen sitting in the verandah, the servants standing outside. I do not know why people always collect their servants and stand them round the front door in India when having photographs taken. It is not the habit at home. I think it must be with a view to introducing the drapery and surroundings of our new lives to our relations elsewhere to whom we send the pictures, more than anything else. At any rate everyone does it, and the native servants like it; indeed now I come to think of it, I am not sure that it is not an arrangement of their own.

Some of the things I shall have to touch on will not be new, I dare say, to readers familiar with India, but there are other friends of Lord William’s to whom the customs and etiquettes are unknown; they may like to have some idea of his life, duties, pleasures and general surroundings, also the way he fulfilled his obligations. Among the latter I must not forget to mention the dutiful way he and his brother officer, Mr. Charles Lascelles, started paying calls after the fashion of the country. Armed with an alarmingly long list, they rode out determinedly from the mess on their ponies. The first bungalow they came to, where they intended to pay their respects, had straw laid down along the road and up to the door. Lord William pulled up, frowning wisely: “We had better call here another day,” he announced, after deep thought. “Why?” asked Mr. Lascelles innocently. “My dear fellow! don’t you see all this straw down? Someone must be ill; having a baby or something most likely,” replied the sage.

Horrified at the thought, and impressed by his friend’s knowledge and insight, Mr. Lascelles agreed fervently, and they rode on to the next bungalow. Here again they found straw laid down.

“Surely they can’t all be doing the same thing at once, can they?” said the astonished Mr. Lascelles.

“You can never be sure what they do out here,” replied the other. “In any case you can’t be too careful.” So they rode on.

To their amazement they found straw at each bungalow, so they returned to the mess to announce the discreet reasons for their failure. The mess was delighted, and it was not till some time after that the two were informed that the straw was there to prevent the prevailing dust from entering the bungalows.

New-comers in India find the rules appertaining to paying calls at times amusing. The first thing that appears strange is the conventional calling hours, being among the hottest in the day, when quite possibly the people being called on are trying to keep cool by lying in baths or under punkahs. A clatter of hoofs is heard, followed by a voice shouting, “Qui Hie!” which means “Somebody.”

There ought to be a servant or two sitting on the verandah, but at times they are not to be found, their beloved hubble-bubbles having enticed them away. So the callers continue riding round the house shouting for “Somebody” plaintively until “Somebody” is found, and a few well-chosen words addressed to him in the visitor’s best Hindustani. Calling out there is altogether an unconventional art.

“LUMTIDDY HALL”

I remember once at Sitapur, where all the officers of a newly arrived battery of artillery dutifully called on us, with exception of a Mr. Ross, who happened to be a particular friend of my husband, so that his non-appearance caused us some surprise. At last he came and apologised for not having been before by saying that he had been awaiting his turn for the calling suit of clothes. Being youngest, his turn came last! Poor soul; he was afterwards frozen to death in the Afghan War. Found dead, still sitting erect on his horse.

To return to Lord William; India was not long in finding out that a good sportsman and a judge of racing had arrived in its midst. Before many weeks had passed he had made himself felt, and was to be seen officiating as judge at some pony races. His first appearance in the pig-skin was in October of the same year (1875), when he rode a raw, hard-mouthed horse named Clarion for a friend in the Grand Military Chase, having amongst his opponents that well-known splendid horseman Frank Johnson, who won on a horse called Ring, Clarion being third. After this he continued to ride a number of mounts for friends and acquaintances.

It was about this time that Lord William was appointed A.D.C. on the staff of the retiring Viceroy, Lord Northbrook, who was being succeeded by Lord Lytton, one of Disraeli’s appointments. While learning his new duties at Calcutta, Lord William did a little racing, winning the Corinthian Purse on a black Waler called Dandynong, for his friend Captain Davidson, the Prince of Wales being present at the time. It did not take him long to master the duties of an A.D.C. or to become popular, for he really commenced a new era in the social life of India. Things began to hum, and everyone began to enjoy the races, dances, picnics and paper-chases he inaugurated. He was soon surrounded with friends.

When Lord Lytton took over the Viceroyalty he retained Lord William as A.D.C. on his staff. In April of that year, Colonel Colley, who was Military Secretary to the Viceroy, wrote, in a letter to Lady Lytton: “Lord William Beresford is full of fun and go, and is being placed in charge of the stables.” So he was already doing the work and fitting into the corner for which he was so admirably suited.

The summer of ’76 was spent at Simla, his first introduction to the place where he was to spend so many summers of his life.

In a letter written home at this time, he speaks of being happy with the Lyttons, and pleasure at having the management of the horses.

9TH LANCERS’ MESS, SIALKÔTE, 1876

Lady Lytton, referring to this time, says: “I noted that Lord William managed the stables admirably, and our coachman Wilson was very happy under him”; from which it may be inferred that Wilson was a good servant, or he would not have been happy under Lord William’s eye, for he was very particular, and would not be content unless everything was properly turned out and in perfect order. It may not be generally known that only three people are allowed to have carriages in Simla, namely, the Viceroy, the Commander-in-Chief and the Chief Commissioner of the North-West Provinces. The Viceregal party are often the only ones to avail themselves of this privilege. The rule sounds a little selfish and high-handed, but it is explained by the fact that there is only one road where it is possible to drive, and that one is very circumscribed. The inhabitants of the station live in houses dotted about the hillside, approached in many cases by scrambling paths, up which people have to be carried in janpans (a sort of chair slung on bamboo poles and carried by four bearers), ride, or in a rickshaw, a sort of bath chair pulled by native servants.

Carriages are therefore white elephants in the hills; and even for riding it is necessary to have sure-footed and quiet ponies.

There are so many books dealing with Indian life I feel that it is rather superfluous to explain that the official residence of the Government is, during the summer, at Simla, and at Calcutta in winter. Lord Lawrence, the Viceroy in 1863, first started Simla as the official summer residence, taking all his assistants and council with him, the reason that this particular station was chosen being that it was the only place in the Himalayas, or indeed any of the Indian mountains, where there was sufficient accommodation for the followers in his train. It was also easy of access and had a good road to it, compared with those of the other hill stations. Of course, like most innovations, it met with a certain amount of grumbling from those who considered they could have chosen a better spot, and each successive administrator tried to go one better by suggesting some other place. Up to now, no other place has been found more suitable, so it may be taken for granted that Lord Lawrence made a wise choice. Anything less like a government house, at that time, than the Viceregal Lodge, rejoicing in the name of Peterhoff, it would be difficult to imagine, being nothing more or less than a glorified bungalow, standing on the edge of what in England we should call a precipice, and in India a hillside or khud, and with very little ground round it.

Having heard that there was a racecourse, Lord William, in his first spare moments, went to see it, finding this dignified title applied to a small, more or less flat piece of ground lying between two hills, the roads to it being zigzag paths, hollowed out by the mountain torrents during the winter and monsoon, to which a little assistance was given by the authorities to make them safe. No carriage could get there, nevertheless this little spot was a source of joy and health to many, for here every Saturday races were held, occasional cricket matches, and other health and pleasure giving exercises, to which all the inhabitants and visitors thronged. All the world and his wife used to go, also other people’s wives, for there are always any number of grace widows in the hill stations, whose husbands are unable to get leave to accompany them, or at any rate only for a short time. Annandale was the name of this little basin where the races were run at that time. I was introduced to it a few years later, and thought its primitiveness added to its charm. There was no such a thing as a grand stand, or even an un-grand one. People sat about on the hillside to watch the racing. There was a small shed, if I remember rightly, where Reigning Royalty could shelter, should the necessity arise, which formed a sort of holy of holies where they could carry out the exclusiveness necessary to their position, so odious and trying to many of them.

Now there is a gorgeous thing in pavilions, as will be seen by the photograph, but I do not feel any ambition to go there, liking the memory of Annandale as it was in earlier times too well to have any desires for buildings comfortable or otherwise, in that historic little corner. After a race meeting there was a general scramble up the hillside again to dress for dinner and the evening’s amusements, of which there were plenty; Lord William took care of that; theatricals, dances, concerts, Christy Minstrel performances, and at times quite classic and dignified oratorios, besides endless private parties and social gatherings.

Government House has to fulfil its obligations, and give a certain number of dances and parties, so has the Commander-in-Chief and the Governor of the North-West Provinces, this being one of the things they are out there for. Some live up to the letter of the law, so to speak, others are full of hospitality and private enterprise, especially those with young people of their own out there with them.

On August 6th there were great rejoicings, a son being born to Lord Lytton, who was away in the hills at the time in connection with his work. Lady Lytton, in a letter speaking of the many kindnesses of their A.D.C., says: “Lord William rode twenty-six miles to Fagoo with letters (to Lord Lytton), and brought me back the answers and congratulations the same evening,” which is just the kindly sympathetic thing he would do.

The work and responsibility attached to the life of a Viceroy is great and anxious. It is well that he should have sympathetic workers under him who will relieve him, as much as possible, of all unnecessary worries and anxieties. Lord William felt this keenly, and all the Viceroys he served under expressed their gratitude for his never-failing thoughtfulness and unselfish devotion.

When it is realised that this one man, with his handful of councillors, keeps in touch with 207,000,000 Brahmins, 9,000,000 Buddhists, 62,000,000 Mohammedans, 2,000,000 Sikhs, 1,300,000 Janns, 94,000 Zoroastrians (Parsees) and 8,000 Jews, not counting the 8,000,000 of the aboriginal tribes whose religion I do not know, considers all their grievances, studies carefully all their superstitions and traditional etiquettes, managing to keep all more or less happy, it seems a superhuman task.

That such comparative contentment reigns is eloquent of the amount of thought and care devoted to the smallest detail of government. Lord Lytton came to the country knowing little of it or its people, but quickly made a study of both, and was deeply interested.

It has always struck me that Lord Lytton’s way of expressing himself was exceptionally charming. His letters home, and to the Queen during anxious times, are delightful to read. Lord William described him as a most considerate Chief, and regretted that he was not stronger, as he was so keen, and worked so hard, that he exhausted himself. The years of the Lytton administration were full of anxious and busy times.

In October, Lord William found time to ride a race or two at Dehra, winning one, thanks to good judgment and riding, on Red Eagle for a friend, also the Doon Chase on Commodore for Captain Maunsell.

A little later, at Umballa, he rode for Mr. George Thomas, and won a hurdle race on Fireman. On returning to Calcutta from Simla he was elected a steward of the Calcutta races, having already joined the Turf Club. Among the other stewards for the year were Lord Ulick Browne, the Hon. W. F. McDonnell, and Captain Ben Roberts.

It is a matter of regret that in the early years of Lord William’s sojourn in India, there was practically no sporting paper to chronicle his many endeavours and triumphs; the only thing of the kind being a rather superannuated Oriental Sporting Magazine, which was more or less in a moribund condition, although run by good sportsmen, some of whom were, perhaps, growing a little out of touch with the views of the rising generation. It was not until 1878 that The Asian was started as a sporting venture, by an energetic person called Mr. William Targett, who, though he knew nothing about horses, felt that he was filling a long-standing want, which the success of his paper proved to have been a correct and business-like surmise. The paper may still be doing useful work for all I know, although it has lost its original and popular proprietor, whom Lord William liked so well. While speaking of The Asian and Mr. Targett I think the following little story is interesting.

Mr. Targett was at home in 1894 on one of the holidays he allowed himself every three years. The time was drawing near for his return to India, so some of his oldest friends in this country convened a little “au revoir” banquet at the Victoria Club in Wellington Street.

Fully a hundred sat down, all good sportsmen hail-fellow-well-met. Mr. Targett was evidently much pleased at the kindly feeling that had prompted his friends to give him this send-off. All were in their places except the intended president. Suddenly the door flew open and the voice of the arranger of this merry meeting announced: “Gentlemen, allow me to introduce your chairman, Lord William Beresford.” Many present knew he was in England, but few that he was in London, therefore little did they expect his presence. This surprise was arranged between Lord William and Mr. Meyrick (the well-known writer of “Sporting Notes” in the Sporting Times) with a view to giving the proprietor of The Asian pleasure.

Mr. William Targett was delighted, and grasped his lordship’s hand, saying: “What, you here, Bill!” The quick reply came: “Yes, Bill; I’m here and so pleased at the invitation!” Wherever Lord William was, there it was lively, and this feast lasted three good hours, until he was obliged to keep what he referred to as an “austere appointment,” but at the end of his response to the toast of his health he took the whole room into his confidence with the concluding sentence: “Gentlemen, while you are thinking about your Christmas dinner, Targett and myself, with good luck, hope to be on the Calcutta racecourse; and I must tell you that this week I have, I think, purchased the winner of the Viceroy Cup—Metallic—for my old friend Orr-Ewing. Good night and good luck to you all.”

One jubilant and well-known Umballian present shouted: “I am betting on the Viceroy’s Cup. Who wants to back his lordship’s tip?” He quickly found customers. The recounter of this story to me added that he risked a little bit, and was pleased to find on the following Christmas week that Metallic had won, and he therefore the better off by a “tenner.” It was kind of Lord William to find time to give his little Calcutta friend this pleasant surprise, considering that every one of his own friends and relations were clamouring for his time.

But to return to 1876 in the East. At the close of the year, all official India, and a great deal of the unofficial, gathered at Delhi for the Proclamation of the Queen as Empress of India on January 1st, 1877. This entailed unceasing work on the Vice-regal staff, and all Government officials, both civil and military. The assemblage was to last fourteen days, and the heads of every departmental government in India were to be present, besides 14,000 troops, seventy-seven ruling princes and chiefs, and 68,000 people were invited and actually stayed in or around Delhi.

Only those who have been in the vicinity of, or engaged in, the preparations for any big gathering in India can imagine for a moment the amount of galloping and fuss, the thraldom of official red tape and etiquette to be punctiliously observed, the number of contradictory orders, the hurt feelings and notes of explanation that are flying about; most of this galloping, between head-quarters and heads of departments, being carried out by the A.D.C.’s.

At last everything was growing shipshape, and people left off saying, “I told you so,” even began to smile furtively once more, for all was in readiness. The Rajahs’ gardens were laid out elaborately round their different tents and camps, each vying with the other to have the best and most attractive display. The elephants had arrived and were amiable and docile. The Rajahs’ horses in readiness, with magenta tails and gorgeous trappings. The jewels laid out and counted. Everything, in fact, ready for the great day. Therefore a little relaxation was considered consistent with good form on the part of the staff and officers in waiting for the great event, consequently a game of polo was arranged for Christmas Day.

This chance game, a thing born of a few spare hours in the midst of the pomp and glitter of Eastern rejoicing, was destined to prove the blackest sorrow of Lord William’s life. Captain Clayton had become to Lord William, what is perhaps the most irreplaceable thing in the world, his best friend, and during this game their ponies cannoned into one another. Captain Clayton’s fell; its rider was picked up unconscious, and died the same night.

THE DELHI DURBAR, 1877

Poor Lord William was wild with grief, and Captain De la Garde Grissell, an old friend and brother officer of his, who was in the camp with the 11th Hussars, was sent for to the Viceroy’s camp to stay with Lord William during the night. Captain Eustace Vesey and Captain Charles Muir sat up with Captain Clayton until he died at midnight. Captain Grissell tells me that they were so anxious that none should do anything for their dear friend but those who had known and cared for him, that he and Captain Vesey made all the arrangements—in India everything has to be carried out so swiftly. There was no undertaker, so a soldier made the coffin and Captain Grissell himself screwed down the lid, both he and Captain Vesey being greatly overcome. The funeral was next day, and a most impressive sight, all the troops at the Durbar taking part. A military funeral is at all times impressive, indeed harrowing, to those who mourn the loss of one who has shared their lives, but it becomes doubly so when the circumstances have been so tragic. He was buried in the graveyard behind the ridge held so long by us during the Mutiny, and he lies with the 9th Lancers who fell at that time and are buried close by.

All the rest of the time Lord William was in India he used to go away by himself on the anniversary of that terrible accident and visit his friend’s grave. So great had the grief been to him that he always felt that he must be alone on that day; alone with his grief and the spirit of his old friend. He did not want to speak; not because there is anything in life too sacred to say or tell, but much too sacred to parody. But the world and all its shows will not stand still for us while we grieve, and Lord William with his good pluck struggled to perform his duties at the Durbar, working so hard that he only had time for a couple of hours’ sleep out of the twenty-four. The strain was too much for him, and he fainted while sitting on his horse and had to be carried away.

His heart and courage were always too big for his body and strength. Captain Clayton had been his life-long friend, and what made him feel it even more, was the thought that through his pal’s death he had gained his troop.

The actual Durbar appears to have been a success, and the Maharajahs and Princes were so pleased that they each wished to present a bejewelled crown to the Empress Queen, but Lord Lytton, with some of his well-chosen phrases, expressed appreciation, and explained that it would not be expedient, for in the first place the Queen would have a crown for nearly every day in the year, and secondly, it might lead to jealousy and heart bitterness, better avoided, which explanation appeared to be conclusive and void of offence.

On Friday, January 6th, Lord Lytton held a review of all the troops, preceded by a march past of those attached to the native Princes in Delhi.

At this time Lord William was still hard at work studying the etiquettes, ritual, superstitions, religions, and dignified ceremonials so dear to the heart of Orientals, who are all great observers of ceremony. The study fascinated him, and proved of great use later in assisting those he worked for; knowing what to avoid and where to give pleasure. No one can hope to fill any responsible position in India who has not studied and had long education in these matters, and this was so quickly grasped by Lord William, that to the end of his days the Rajahs were among his most faithful friends and admirers.

By January 15th the Viceroy was back in Calcutta, and Lord William riding in races again. He had one of his bad falls in a steeplechase, hurting his nose considerably, besides receiving other injuries. As usual he tried to make light of them, but collapsed and had to be carried home.

Before closing this chapter it will be interesting both to Captain Clayton’s and Lord William’s friends who may not already be acquainted with the fact to know that there is a marble tablet in the church at Curraghmore, placed there by the fifth Marquis of Waterford:

In affectionate remembrance of

William Clayton Clayton,

Captain, 9th Lancers.

For many years the dearest friend of the House of

Curraghmore.

Born April 23rd, 1839. Killed while playing polo

at Delhi, Christmas Day, 1876.

Another instance of the respect and affection with which Captain Clayton was regarded at Harrow-on-the-Hill, where he was educated. There is a white marble cross in the churchyard, the inscription on the base being:—

In loving memory of

William Clayton Clayton,

Captain, 9th Queen’s Own Royal Lancers.

Born April 23rd, 1839.

Killed while playing polo at Delhi, India, Dec., 1876.

Oh, the merry laughing comrade,

Oh, the true and kindly friend,

Growing hopes and lofty courage,

Love and life and this the end!

He the young and strong who cherished

Noble longings for the strife,

By the roadside fell and perished,

Weary with the March of Life.

So great was the feeling of loss at his death that old friends, Harrovians, soldiers, and indeed those of all classes who knew him, wished to do something to perpetuate his name, and decided to found a scholarship. Subscriptions flowed in, and in 1881 the Clayton Scholarship was founded, valued £40 a year, tenable for three years at Harrow School.

Lasting affection of this kind is not inspired by any but good men, and speaks better for the character of the individual than any words of mine, for words are poor impotent things. England, prolific though she be in men of courage and manliness, can ill spare one of her sons when of the nature of Captain Clayton, whose influence was everywhere for good.