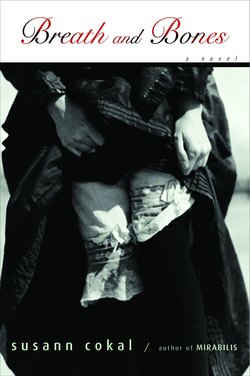

Читать книгу Breath and Bones - Susan Cokal - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Kapitel 2

ОглавлениеEnglish is spoken at all the principal hotels and shops. A brief notice of a few of the peculiarities of the Danish language may, however, prove useful. The pronunciation is more like German than English: a is pronounced like ah, e like eh, ø or ö like the German ö or French eu. The plural of substantives is sometimes formed by adding e or er, and sometimes the singular remains unaltered.

K. BAEDEKER,

NORTHERN GERMANY (WITH EXCURSIONS TO COPENHAGEN, VIENNA, AND SWITZERLAND)

Famke was not virtuous when she met Albert Castle. According to the Catholic precepts by which she’d been raised, she was no longer truly virginal, as she confessed to him in a bedtime conversation. Few orphan girls, even those raised by the good sisters of the Convent of the Immaculate Heart of Mary, could lay claim to that desirable state once they entered the wider world—and why should they bother to hold on to something that would be taken from them once they’d passed communion and were placed in service with some family inevitably headed by a prurient husband, a curious son, or a querulous grandfather who would have his way?

“Darling, you’re so fierce,” Albert said as he squeezed her.

“It is a fierce world,” she said. “Overhovedet, especially, for a girl.”

Besides, immured in her orphanage, Famke had found the idea of sin exciting. It offered the possibility of something other than what she had, something that must be at least pleasant, if not delicious, since the straight-backed nuns who had married Christ were so vehemently against it.

So Famke had taken sin into her own hands. The boys on the other side of the orphanage were just as curious as she, and intrigued by her interest. She courted them first through a crack in the wall separating the boys’ and girls’ dormitories. This was during the exercise period, when the children were encouraged to enjoy fresh air and wholesome movement, trotting up and down two barren courtyards, occasionally playing desultory games of tag or statue around the lone elder tree in each one. Famke would lean into her wall and see an eye, almost always blue, peering back at her through the rubble and leaves. They would talk, whispering arrangements for rendezvous that, under the nuns’ watchful glare, never came to pass. Once, Famke wormed her thin hand along the crack, and the boy on the other side (a Mogens, she believed, or maybe a Viggo—there were so many of both, arriving with those un-Catholic names pinned to their diapers so the good nuns felt bound to retain them) managed to reach just far enough in to touch the tip of one finger. The contact gave her a thrill she’d never known before, and for a good many months it was what she thought sin was, this furtive touch within a wall.

She actually saw boys only during the daily chapel services; the sexes even ate separately, so as to avoid the inevitable temptation. While the priest droned on about the blessings of humility, meekness, and poverty, she flirted through fanned fingers. Breathing deeply, she smelled the strong cheap soap the older girls made in the orphanage yard from ash and fat. For the rest of her life, it would be that smell—even more than the smell from the place that the nuns would refer to only as Down There, when they admitted it existed at all—that made her heart pound with excitement.

To the priest’s soporific cadences, in that edifice of gray-painted brick, Famke’s azure eyes winked and fluttered. The boys were helpless: She glowed like the rosy windows that Catholics could afford only in non-Lutheran countries. At the age of twelve, her breasts already brushed against the plain gray uniform, and the figure growing inside that rough sacking seemed to color it rainbow bright.

The nuns did not fail to notice her blossoming. Soon, Famke had to sit through services sandwiched between two severe gray bodies.

“She has always been wild,” the Mother Superior said in one of her frequent conferences with the wisest of the nuns. “We saw that from the first.”

“And the visitors saw it as well,” said Sister Saint Bernard, Mother Superior’s second in command. “The basest peasant can recognize such a spirit, be the little girl ever so pretty. It’s no wonder they always took a different child.”

Mother Superior said absently, “We do not speak of our patrons that way. Or our young charges.” She was thinking, as was the rest of her council, of the high hopes they’d entertained when the baby turned up on their doorstep one late October day, still wearing the black hair of the womb, wrapped in a soft wool blanket and bearing a note that said simply, “Familjeflicka.” This, they had thought, was a child destined for one of their rare adoptions.

Young Sister Birgit, who had been born in southern Sweden, had said the word came from her country and meant either “a girl who stays at home” or “a girl of good family.” Given the quality of the blanket and the notorious fact that gravid Swedes often took the short boat ride over to Copenhagen, where mothers’ names were not required for a legal delivery, the note seemed to promise great things. But the sisters found no family portraits, no silver spoons, no precious jewels hidden about the infant’s person; only what one might expect to find in a very ordinary baby’s diaper, and that they gave to one of the novices to deal with. The baby screamed at their inspection, and screamed when she was washed, and nearly took her own head off when she was put to bed with a bottle. The sisters decided to let her cry till she slept, and in the morning they found her whimpering more quietly, but with a mouth stained from blood, not milk. Her tough young gums had broken off the glass nipple.

Sister Birgit was delegated to pick the splinters from the baby’s lips, using tweezers and the light of a good lantern. She had to dose the squalling patient with brandy to make her lie still.

She’s nothing but breath and bones, Birgit thought. Only breath and bones. Though it wasn’t true—the baby’s limbs were nicely rounded, her cries lusty—the phrase made Birgit feel tender. It gave her patience.

In the meticulous work, which took all day, Birgit came to love the little girl. She murmured endearments over the drunken body and torn mouth, and it was then that she shortened the Swedish word to “Famke,” the name that would follow the girl even after her official christening as Ursula Marie. When Famke woke up enough to be hungry again, Birgit would have fed the baby at her own breast, if she could have mustered anything more than prayers. Instead she dipped one corner of Famke’s blanket in a cup of warm milk, freshly bought at the market on Amagertorv, and coaxed the sore lips and tongue to suckle.

In later years, as the growing girl’s cough turned bloody, Sister Birgit would accuse herself of having missed a shard of glass somewhere. She fancied that Famke’s lungs were lacerating themselves as they tried to get rid of that last fragment. Though Birgit and many of the other nuns were also afflicted with persistent coughing, she felt, against all reason, that the unusual event of Famke’s infancy was the source of the girl’s affliction—never mind that she bore no other scars. Birgit prayed for forgiveness, and for Famke’s cure, and she nursed Famke all the way to solid food at the age of five months. Thus she made the best possible use of the “good family’s” sole patrimony; the baby sucked the blanket down to meager threads.

“Sister Birgit,” the Mother Superior reprimanded her gently in private, “you have become too attached to this one child. You must divide your care among the children equally, as our Lord divides his love among us.”

Birgit tried to do as she was told. Though she could never give the chaotic horde of orphans the impartial and impersonal affection required by her order, she could offer them the semblance of equal treatment. In everyday life, the life the other sisters shared, she nursed the orphans’ colds and coughs and combed their hair with the impartiality of a Solomon; when a child died, Birgit washed the body and lifted it into its pine box.

But when she was alone with Famke, Birgit hugged the little girl as tight as she dared, so tight that their bones ground together. Birgit would not have chosen convent life for herself; that had been her parents’ wish, as they’d grown too old and tired by the time their seventh daughter reached adolescence to do anything more for her. Her eighteen-year-old body was starved for physical contact, and Famke’s round little arms gave her the greatest comfort she would ever know.

In these moments of privacy, Famke took shameless advantage of Birgit’s unstated preference. She played by sliding the gold band from the nun’s finger and sticking it on her own thumb, then popped it in her mouth and impaled it with her tongue to make herself laugh. On the unusual occasions when there was candy at the orphanage, Famke knew that even after all the other children had received their justly measured shares, there would be an extra piece or two in Birgit’s pocket. She knew also that if Birgit, and Birgit alone, caught her in some wrongdoing, she had only to place her hands on each side of the nun’s face and kiss her nose to be forgiven and pass unpunished. No one else would learn of her crime, and her bond with her fellow-Swede would grow.

In Famke’s twelfth year, Birgit’s affections led nearly to disaster. As one of the physically stronger nuns, Birgit was asked to supervise the annual boiling of soap. She had been doing it for some years and had the routine chore mastered: rendering the waste fat saved from stringy Sunday joints, adding lye made from stove ashes, stirring endlessly. The older girls were excused from lessons in order to perform this stirring, for production of a good soap, the nuns argued, was of as valuable practical use as hemming the countless towels and blankets they made to sell—all skills the girls would take with them into service—and perhaps even more necessary than lessons in the use of Danish flowers and herbs, or reading the Bible and other useful books.

That year, Famke was big enough to help. Sister Birgit smiled as her darling took the wooden stirring-stick from the orphan ahead of her and began to draw it through the liquid viscous with long boiling. Famke closed her eyes and breathed in the odor that, to her, meant the belly-fluttering thrill of flirtation and the promise of something she didn’t understand but knew, absolutely knew, would be wonderful. And so when one of the older Viggos, a large-eyed youth now nearing the age of confirmation, approached with wood for the fire, Famke smiled and shimmered at him. And he was lost.

Just then Birgit’s attention was momentarily diverted—and for this the other sisters blamed her—by a cloud of bees threatening to swarm either the soap pot, the heavy-blossomed elder tree near which it rested, or the fair stirrer of soap herself. Birgit took off her apron and flapped it vigorously at them. So she did not see Famke slow down in her stirring, gazing at this Viggo, lost in her own hazy ideas of sin. And then Famke lost the wooden plank, or most of it, in the soap pot. With a cry of dismay, she lunged after it; the boy dropped his wood and lunged, too, to save her hand from scalding—and as a result it was his hands that scalded.

Viggo howled with pain and ran toward the well. Famke ran after him. She nursed his burned hands as she’d been trained to do, with cold water and bandages swiftly torn from her petticoat. And finally, as a much-stung Sister Birgit abandoned the bees and came to the rescue, Famke dropped a tiny illicit kiss on one clumsy knot she’d tied over the boy’s wrist.

In that moment, with no interchange of plank and air to cool it, the unstirred fat reached a crucial temperature. The whole soapy potful burst into flames. The conflagration blew toward the elder tree and, as Mother Superior said in yet another council meeting, “We were an angel’s breath from burning up ourselves.”

Indeed, a spark landed in Famke’s hair and started to melt. With a hurt hand, Viggo smothered it, and Famke collapsed in his arms in gratitude. She never mentioned the singeing of her braids to anyone else, but she was to suffer a fear of fire the rest of her life.

Sitting and tallying up the damage, Mother Superior said, “I believe some punishment is in order. For endangering not just herself and young Viggo but the entire orphanage as well, for being . . . Nå, for . . .” Everyone on the nuns’ council knew what she meant. Famke had been born with a character that had no place inside convent walls, and Sister Birgit had only strengthened it. They were all thinking one word: wild. “This time her transgression itself was slight, but it might have had serious consequences for all of us.”

Sister Saint Bernard said cryptically, “When Lucifer and his angels fell from heaven, their wings burst into flames.”

“Så,” said the Mother Superior, “it is time to take Ursula in charge.”

Birgit prayed for humility and for strength. She knew she was to be disciplined by having to join in the disciplining of her favorite, and she could say nothing aloud just yet.

“She should be isolated from the other children,” suggested Sister Casilde.

“She should have bread and water for a week,” countered Sister Balbina.

“Bread and water and isolation,” said Sister Saint Bernard, sending up a quiet prayer of thanks that the year’s vintage of elderberry jam and wine had not been threatened.

The nuns discussed this punishment eagerly, piling on mortifications that they themselves might have embraced in a more idealistic, ascetic order. One sister, who had been in the convent so long that she’d gone deaf with the silence, even shouted that Famke should wear a hair shirt.

“Sisters!” Birgit bit her lower lip, shocked at her own forcefulness. What could she, so largely responsible for the disaster, say to them? “Famke is just a child—”

“Her first communion is not far away.” Sister Casilde offered the sacrament as a threat.

“Punishment will do no good,” Birgit said with the authority of the one who knew Famke best. “She is wild, yes, but we must tame her gently. Violent restrictions will only make her rebel—and she only dropped a spoon, after all.”

The other nuns gaped.

“Our order does not advocate violence,” Mother Superior told Birgit on a note of reproof. “No one suggests we cane her, for example.”

“It would not be a bad idea,” Sister Saint Bernard said under her breath.

Birgit pressed her palms against the table. “I am to blame,” she declared loudly. “I should have been watching her. So I will do penance, say extra prayers . . . I will wear a hair shirt, if that is required.”

The nuns stared. They had never seen such passion in Birgit before. Nearly all felt a little ashamed; each asked herself, Would I wear a hair shirt for someone else’s sin?

Mother Superior relented. “And Ursula will pray with you. No hair shirt will be necessary.”

While Birgit prayed, the good sisters plotted a course of action. One after another, they lectured Famke about minding the clock and always, always keeping her eye on a burning fire. Sister Fina instructed her to sleep on a wooden board, Sister Agnes to cross her ankles, never her knees, when seated. Mother Superior had her read stories of the saints’ lives to the younger children—endless tales of patience and suffering, including the story of Famke’s own namesake, Saint Ursula, who had fled pagan England with an army of eleven thousand virgins only to be mown down in Germany.

Sister Saint Bernard swore her to secrecy and gave her five good whacks across the bottom with a cane.

Knowing this was mercy, and feeling very bad over what had happened to Viggo, Famke obeyed them all. She adapted easily to the manners of a good girl—but they suspected she would as naturally have taken on those of a strumpet. So she was forced to bide her time, peeking through the prayerful fan of her fingers with a nun on each side.

“Why do you twitch so?” she whispered, sitting next to Birgit; but the nun said nothing, having resolved, despite Mother Superior’s injunction, to wear the hair shirt in silent mortification for three full months.

At the end of that time, Viggo’s hand had scabbed over nicely and the women hoped he would one day be able to use it again to lift a pitchfork or curry a horse. A bumper crop of elderberries allowed Sister Saint Bernard to forgive both Birgit and Famke, and Famke forgave herself. She began begging to help with tasks that would bring her to the other side of the orphanage.

But, bolstered by her own penance, Birgit held firm. She kept the girl with her during exercise periods, and she herself plastered every chink she could find in the dividing wall.

“You will understand one day,” she said as she brushed Famke’s mass of red curls before bed, “and you will be grateful.”

“But in the outside world,” Famke pointed out, “there will be nothing to save me. Shouldn’t I learn the worst of it now, while I still have you with me?”

Birgit gave a few vigorous strokes to a particularly stubborn tangle. “Perhaps you won’t need to join the outside world. Perhaps you’ll stay here . . .”

“What, with you?” Famke turned and gave her a big hug, slightly frightening to Birgit in its intensity. “I would love to stay with you. But I’ll never be a sister. Instead, maybe I’ll take you with me when I go into service.”

Birgit picked up the brush again, disciplining herself to make firm, even strokes, and then to braid the girl’s hair tight. “What would I do in the outside?” she asked.

Since it was impossible to reach the boys’ side of the building, Famke turned her attention to the part she herself occupied. At night in the dormitory, she lay awake listening to the other girls breathe, feeling the heat radiate from their bodies. She wondered why she had never noticed that Anna had a loud, tickling laugh or that Mathilde’s hair was long and bright. Mathilde also had large and capable hands that nonetheless managed to look graceful as they scrubbed out a pot or picked up a stitch dropped in Famke’s knitting. Mathilde smelled good, like bread and soap. She began to interest Famke very much.

She was thirteen, a year older than Famke and a suitable model for the younger girl’s reformation. The nuns looked on their friendship with relief and, as Famke took on some of Mathilde’s habits, with complacency. They saw that she washed herself frequently, volunteered to help deworm the littlest orphans, and even rose early, with Mathilde, to make breakfast.

Famke’s hair curled in the steam as she stirred the enormous kettle of havremels grød, the oatmeal gruel they ate each morning. Through the dully fragrant cloud of it, her eyes kept seeking Mathilde. She knew no love poetry, except what was found in the Bible, but she thought there must be some nice way to describe the curve of Mathilde’s back as she bent over the bread board, or the graceful undulations of her hands as she kneaded the dough.

“You look like a fish,” Famke blurted out, and Mathilde’s eyes got wide. Then, out of embarrassment, Famke laughed; and Mathilde, with an affronted air, turned wordlessly back to her work.

In the end, won over or perhaps worn down by that persistent blue stare, it was Mathilde who approached Famke over the bubbling pots, who kissed her and set her heart pounding, who held Famke close and hard and gave her a taste of that delicious, elusive shimmering feeling.

“You are my little fish,” Mathilde whispered into the red curls. Famke felt glad all over.

That night she was awakened with a tickle in one tightly curled ear. “Let me in,” Mathilde whispered, tugging at the blankets that the nuns always snugged like winding-sheets around the children’s bodies.

Famke wiggled herself free, emerging from her cocoon warm and white and fragrant. Mathilde slid in beside her and, with little ado, put her supple lips up to Famke’s, her hand on the region Down There.

Famke jumped. “Fanden,” she swore, daring to speak the name of the devil for the first time ever.

“It’s all right,” Mathilde whispered, touching Famke through her nightgown. “You see, there is a little cottage Down There, with a little roof of thatch. A little fire burns on the hearth.”

If there was indeed a fire, it was drawing water to it; but the water did not quench, only made the fire hotter. Famke remembered the day of soap and flames: the smell of ashes and fat, the heat of Viggo’s hand under her lips.

Mathilde’s finger moved. “The cottager comes home to warm himself.” But the cottage door was closed, and Famke yelped in pain.

“I see.” Mathilde propped herself up on an elbow and retreated to the roof of thatch. “The cottage-wife has built herself a wall. Shall I look for a window?”

Mathilde’s hair shone white in the light of her eyes, and all around them the darkness crepitated. Famke realized that cottagers were coming home in the ward’s other beds too. That thought made her bold, and curious; her fingertips itched.

With the swift motion of sudden decision, Famke pushed aside the other girl’s nightgown. “There is a net. There is a fish and—a pond? Yes, a deep, deep pond . . .”

“Be careful,” Mathilde whispered breathlessly; “there must be nothing larger than a fish. Someday I shall be married.”

It was the first and for a long time the only secret Famke had from Birgit.

“A schoolful of Sapphos,” Albert said when she told him, laughing out a puff of smoke. “What a picture that would make. A cottage . . . a pond . . .” He hugged her close to his chest and deposited a kiss of his own on the crown of her head. She felt him stirring against her hip, and that was all she needed to know about anyone called Sappho.

Famke told him, with an air of great revelation, that romantic attachments were not uncommon among the older girls, or even among the novices who were expected to take holy orders. Some of the girls swore these orphan embraces would prove the best of love, for they came without responsibility, without danger, without babies. But somehow they weren’t enough for Famke. She longed for the open space beyond the orphanage wall, for the freedom she associated with the wind that occasionally rattled the leaves of the elder trees; for the forbidden boys.

Famke was sad when Mathilde left, placed out in the village of Humlebæk. But then there was Karin, and then Marie. Famke became a fish herself, swimming through the ranks of girls, toppling them onto their backs with a flip of her tail. But she was careful to stay on the shore of every pond, the doorstep of every cottage; each Immaculate Heart girl who managed to marry bore all the signs of innocence to her husband.

And soon enough it was time for Famke to go. At fourteen, she’d finally been confirmed; she was capable of earning a woman’s wages, and there was no reason to burden the city’s few Catholics any longer. Sister Saint Bernard was in charge of placing the grown orphans, and she found a position for Famke as a goose girl and maid-of-all-work in a village called Dragør. Famke mucked out the goose pen, made cheese, and fended off the attentions of the gristled farmer who’d consented to take her. She talked to the girls on the neighboring farms—none of them smelling of soap or bread or ponds, only sweat and dung—and concluded that it would be no better anywhere else; so she hid her unhappiness even in her monthly letters to Sister Birgit. For her second Christmas, Famke’s employer allowed a traveling neighbor to carry her to the orphanage with a couple of geese he’d had her kill and pluck. She attended Mass, turned the geese on a spit, and hardly had time to exchange two words with Sister Birgit; but she set off for the farm in new Swedish leather shoes.

There was no cart now, and no one on the road. Famke had walked halfway to Dragør when a fit of coughing doubled her over. Her mouth was suddenly full and tasted horrible—so she spat into the snow and saw a drop of blood. It froze quickly, to glow like a ruby in a bed of spun silk. She kicked the snow over it and walked on, refusing to think of what that droplet meant.

Summer came, and Dragør steamed. Famke told herself she was resigned to her lot. She let the farmer kiss her cheek and even, once, put his hand on her bodice. She attended services at the village Lutheran church and talked to the other farm girls. She met young men, too—hired boys in no position to marry; they gazed at her with the same covetous eyes she saw in the farmer. None of them managed to interest her.

But then, wonder of wonders, a foreigner appeared, dressed in blue and driving a carriage. He stood a long while at the fence rail, watching her shovel out the goose pen; he held a leather-bound book before him and a pencil in his hand. From time to time she wiped the sweat from her face onto her sleeve and cast him a glance from the corner of her eye. When at last he approached, she saw his book contained a collection of drawings. He turned the pages back to reveal a moth, a chicken, and one of her.

There she was—she who had rarely seen her own face in a mirror—with all her busy motion stilled, looking slyly up from a white page. The real Famke, living and flushed, straightened her apron and pushed her hair under her cap, trying to look like the good Christian maiden she’d been raised to be. She knew she reeked of goose.

“Beautiful,” the stranger said in his own tongue, perhaps guessing this word was universal; but she looked at him with the round eyes of confusion. Then a slow smile crept across Famke’s face, to be mirrored in his. She put one damp finger to the page and accidentally smudged the drawing.

In gestures, the stranger asked her to fetch him a glass of water; he pantomimed that his labors had exhausted him. She brought a dipperful from the farmyard well, lukewarm and tasting of the geese and horses and pigs that trotted across the packed earth. As he drank, she took the opportunity to engrave his face and figure onto her mind. He was tall and sticklike, with thin blond hair combed into a semblance of romantic curls; his green eyes immediately reminded her of a frog’s. But he gave her a nice smile with slightly crooked teeth, and he bowed as if to suggest that he considered her every bit as good as he was.

He returned the next day in a carriage decked with flowers, and again she served him a dipperful of water. The flowers drew butterflies; in a cloud of pale yellow and white, their wings dipped from eglantine to glem-mig-ikk’, and she thought she’d never seen anything so pretty. She would find out later that the carriage had been decorated for a wedding; when the young man hired it he had asked to keep the flowers, and the proprietor even threw in a bouquet of lilies left from a more somber occasion. Famke’s suitor handed them over with a flourish, and she blushed. She looked from the carriage to him—“Albert,” he said, with a thump on his chest—and felt her eyes shining.

Albert drank. As he swallowed, his throat made a little croaking noise, and he and Famke laughed together, like old friends. Before she knew it, his hands were making signs to offer her a ride into the city and an engagement as his model and muse. That she would be mistress as well, Famke had no doubt; her fellow-servants in Dragør had told her what young men who fancied themselves artists were like. She watched this one thoughtfully as he argued his case. From time to time clasping her hand, he repeated two words so often they seemed like a name, Lizzie Siddal, though it had no meaning for her. Finally he kissed her grubby sixteen-year-old palm. When she pulled it away and put it to her face, she smelled his soap. Genteel, perfumed, but made of the same basic ingredients as orphanage soap. Ashes and fat. Prayers and hope.

So Albert and Famke rode away in a cloud of heavy dust, with the geese honking and the pigs squealing a charivari of farewell. The butterflies accompanied them, draining a few last drops from the wildflower garlands.

Famke had no notion where he’d take her and was delighted to find herself returning to Copenhagen, to the harbor district of Nyhavn. This time her experience of the town was different, lighter and lovelier, though almost as sequestered as in the orphanage. She stopped wearing the servant-girl caps and utterly abandoned the crossing of her ankles while seated. She found the life of a model so restful that she put on weight, and for the first time her breasts fit the cups of her hands rather than the flats of her palms. From Albert she learned English; she learned to call the shape of her mouth a Cupid’s bow—perfectly formed even after the mishap with her infant bottle—and to appreciate the line where the red of her lips met the white of her flesh. He taught her to read English as well, in the guidebooks he had brought. From them she learned that Denmark was flat and that the Danes were thrifty people who enjoyed flowers, sunshine, and making butter and beer. She much preferred Albert’s version of her country’s history, with the thrilling princesses and long-ago warriors.

Inevitably, she compared being with Albert to being with the orphan girls, and she quickly decided she liked him better. He pleased her in different ways, without hands or mouth, and he took pleasure from the way she sucked on his flat nipples: “No woman has ever done that before,” he gasped. And when they were working, he looked at her the way no girl had ever done—no man, either, for no one before Albert had thought to preserve her and her beauty for the generations.

Albert once explained to Famke that he’d come to Denmark in hopes that, in a land without a significant artistic or cultural tradition, he might find some last remnant of the medieval life depicted by the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood to which he aspired. At home in his father’s overstuffed, overheated rooms, he had thought of Famke’s land as historically backward—or primal, he amended when she’d learned enough to protest the first term—populated by simple peasants in wooden clogs, flower crowns, and brightly colored folk costumes, still living out the stark paradigms of Nordic mythology. He’d found more of the curlicued Renaissance and overstuffed nineteenth century than he’d anticipated, but nonetheless he’d fallen in love.

When Albert said that, Famke felt a thrill in her stomach, as if she were going to be sick, but in a good way. It left her belly tingling. But even though Albert repeated the word “love” quite slowly, she wasn’t sure exactly what it was he’d fallen in love with. Before she could muster the courage to ask, he had moved on to another subject.

“If I hadn’t come here, I would have gone to America. To the west.”

Famke stared up at the ceiling, which was water stained but marvelous, Albert said, for reflecting light onto color. “America . . . But that is so far away, so . . .” At Immaculate Heart, there had been a jigsaw puzzle from America, a picture of a vast snowy mountain ringed with purple wildflowers. The children had called it Mæka.

“That American west is a new land, and it holds a host of wonders for the artist—and yet it has seen no truly great painter. Yes, had I had the funds, that is where I would have gone . . . to the forests primeval, the mountains and plains, the mines, the canyons . . .”

Albert had reason to respect Mæka’s ancient woods, for it was from good American cedar that his family’s fortune had been made. His father would buy nothing else to make the innovative graphite pencils he manufactured, from a money-saving design that allowed six, rather than five, hexagonal cylinders to be cut from one block of wood. And just after Castle, Senior, decided to affirm his new social status by purchasing work from the era’s fashionable artists, Albert’s determination to become one of them had been born. The poet and painter Dante Gabriel Rossetti came to the house to hang the Castles’ first acquisition, a portrait that reminded Albert’s father of the dear wife who had died shortly after presenting him with the boy for whom he had finally found room in his budget. Thin and hollow-eyed, but with a smile and a chin-chuck for little Albert, Rossetti had spent an hour or so in the gloomy cedar-paneled parlor. That brief moment of kindness had been a ray of moonshiney hope for the anxious little boy, who hid behind a tasseled settee and observed the careful measuring of the wall, the straightening of the frame, the earnest discussion between the sober factory man and the painter in prime of life, both widowered. That afternoon, nine-year-old Albert decided to learn this magic trick for pleasing people. He would use every technique in Rossetti’s arsenal: the goddesses, the eye for details, the colors.

To Famke, however, the most beautiful thing he had ever made was that first plain sketch from Dragør. When he wanted to toss it in the fire, claiming it was far from perfect—even far from a likeness—she whisked it out of his hands and wept so stormily that at last he allowed her to tack it to the wall above the washtub. It was the one work that he held inviolate, and as Famke scrubbed at the paint stains on his clothing or soaped her own legs and arms, she liked to look at it.

Her face, looking back at her, forever exactly the same.