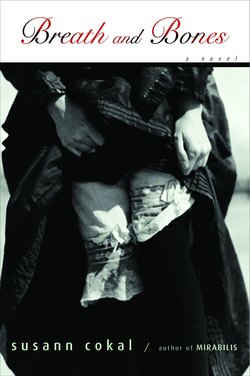

Читать книгу Breath and Bones - Susan Cokal - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Kapitel 3

ОглавлениеThe Danes had a splendid record for fighting in the middle ages and up to the last century, but have become an agricultural people, and their activity is devoted to making butter and beer, and raising poultry and hay. Copenhagen is the only city of any size.

WILLIAM ELEROY CURTIS,

DENMARK, NORWAY, AND SWEDEN

In a rare moment of introspection, it occurred to Famke that other people might consider she was making a fool of herself. She’d thought the same in Dragør about a milkmaid who trailed around after the local doctor, begging for rides in his buggy and dreaming up reasons he should examine her. And at the orphanage, when one of the girls developed a crush on Sister Birgit—the last person, Famke had thought with scorn, who’d look at an orphan that way—Famke had kissed the girl herself and deflected destiny. But now it might seem that she, too, Famke of the Immaculate Heart, had developed hopes above her station.

She was in love, with all the passion and force and urgency and trepidation of her years. She did not precisely look on Albert as a savior, but her life was vastly more enjoyable with him than without, and so he was a sort of hero. She had fallen in love by that first night, with pain and blood marking the sharp dart of love settling into her flesh. He smelled good, including the cheroots. She even loved his odd, froggy eyes, so placid in sleep that she kissed them tenderly as she watched over him. He was the first man she had known well, and because there had been nothing like him in her life before, she occasionally suspected it was foolish to hope he would always be there. And just as quickly, she dismissed those notions—after all, Albert himself told her all those nice fairy tales and myths, and hadn’t he mentioned that the Pre-Raphaelites were prone to marrying their models?

One night, Famke felt Albert prop himself up among the pillows and gaze down at her. “‘He who loveliness hath found,’” she heard him say, “‘he color loves, and . . .’”

Her eyes flew open at that. She rolled over and poked Albert to make him speak more. “John Donne,” he said, laughing. “Color is beauty, and you, darling . . . it would take a whole dye shop to describe you.” Then he sobered and took on that tedious tone of the bedtime lecturer, sinking back against the pillows, telling her about something called Old Masters and the National Gallery, the dulling effects of old varnish and the traditional artists’ mistaken assumption that to paint like the masters they must limit their palettes to gray and brown . . . Albert intended, like his idol Rossetti, to reintroduce color to loveliness.

To Famke, all this meant was that he loved color; and that itself might mean . . .

Love gave her the stamina she needed to pose the long hours Albert demanded of her; and those hours were growing longer and longer, as he had determined that Nimue would be the first picture he finished: She would be perfect, complete, in all senses of the word. Accordingly, he studied the pose from every viewpoint and considered every nuance within the story. He moved the angle of Famke’s arms a degree up or down, adjusted the backward thrust of one leg, tried combinations of hair braided and unbraided while Famke basked like a cat in the feel of his fingers. Again and again her lips, nails, and nipples turned blue, but Albert said that was appropriate—“because even a nymph would feel the chill.”

At last they had the pose just right, and Albert spent some days drawing intently, sometimes in charcoal, sometimes in graphite. He tacked the studies of Famke’s face and body to the walls of their garret. And only when he had the picture fully realized—Famke in her magician’s stance, the dance of her hands shaping turrets of ice—did he begin to prepare his canvas.

Albert had decided that this picture would be big, of a size that only a museum gallery could accommodate properly. He bought four straight pieces of Norwegian fir five and seven feet long. He nailed them together in the loft, borrowing a hammer from the landlady. When the frame wobbled, he acquired four more stakes and nailed them into an airy latticework behind.

From an importer on Bredgade, he bought the finest canvas in Copenhagen. There was no cloth bolt wide enough to cover the entire space, so the lengths had to be sewn together. Even with Famke’s help, the stretching itself took days. They laced all four sides over the frame with a series of cords—not unlike the strings that closed a corset, thought Famke, who longed to wear such a garment herself and feel like a lady.

No easel could support a canvas so tall and heavy, so Albert went back to the lumber dealer and fashioned six little props of wood; three he nailed to the ceiling, and three to the floor. He nailed the fir frame to these blocks, and Famke at last stopped tripping over them. The room’s peaked ceiling was scarcely more than seven feet at its highest point, so the canvas stood there, neatly cleaving the space in two. Albert bought a ladder from a bankrupt apothecary, a vast tarpaulin from a French painter who had married a Dane, and then his workspace was complete: windows, paints, and platform on one side of the canvas; bed, door, and clothes cupboard on the other.

“Subdividing, are ye?” asked the landlady, Fru Strand, when she came to retrieve her hammer. Never having caught on to the niceties of Albert’s profession, she thought he was tiring of Famke and had erected a partition so he wouldn’t have to look at her all day.

When Famke dutifully translated, Albert laughed and offered to buy Fru Strand a pint of frothy Danish beer, which she loved as much as her seafaring tenants did. The two of them stomped downstairs merrily, leaving Famke behind to sweep up the sawdust and bits of canvas thread.

“Subdividing,” she muttered, having taken on Albert’s habit of repetition. She put away the broom and sat down in a chair by the window, to watch the sailors staggering up and down the street like drunken elves in their double-pointed winter hoods. Albert and Fru Strand were nowhere in sight.

That night, and for several nights thereafter, before he would so much as touch Famke, Albert wetted the canvas; every morning he tightened it, until it was so taut it sang like a bell when she tapped it.

Meanwhile, Albert sketched more Nimues. “She must be perfect,” he insisted, shading in a sketch he had allowed to progress rather further than the others.

“Perfect,” Famke echoed. Then she giggled, noticing what Albert habitually omitted. “But no hair,” she said. To her, perfection meant an exact likeness. When Albert blinked at her, she touched the picture and explained, “Down There, she has no hair . . . She hasn’t even a sex. It be as if a cloud passes over.”

“Sexual hair is not a subject for art,” Albert said on a note of reproof. “It is not for ladies to see, even if they know it must be there.”

Famke subsided with, “That is not like nature.” She thought of Albert’s Pik, so surprisingly rosy in its dark-gold nest. She wondered if she should be shyer about looking at it—if perhaps he didn’t like her to look . . . It was the artist’s job to look, and to have opinions, never the model’s.

When she wasn’t posing, there was little for Famke to do. She’d washed all the bedding and every garment the two of them owned, and she’d had a long wash herself. There was nothing left to clean, and no stove on which to cook (for which she, with her dislike of fire, had always been grateful). She had even grown tired of looking at sketches of herself. So when Albert took out his tubes of paint at last, Famke breathed a sigh of relief. But he explained that before he would need her again, he had to lay down a white ground. Layer by infinitesimal layer he built it up, and the seams in the canvas disappeared.

“Let me help you,” Famke begged, eager to hurry the process along. She churned the brush through the thick gesso, and Albert lifted her hand away.

“It must be absolutely even,” he said. “It’s really best that I do this myself.” He explained that only against a smooth, hard whiteness would his colors glow—“and I want you to glow, darling,” he finished. She almost didn’t need him to look at her then; these words were enough to keep her warm for the rest of the day.

The time it took for the white coat to set, they spent in bed. The sun’s hours were getting ever shorter, and despite her boredom during daylight, Famke was quite happy in the dark, keeping Albert gladly distracted.

On the morning that they woke to find the canvas’s final white ground was perfectly smooth, dry, and hard, Albert gulped. He lingered in bed much longer than was his wont, and Famke practically pushed him out of it. “You said today you should start,” she said. “So start!” When still he dallied, looking at the vast blankness with something akin to despair, she got up and led him to the chamberpot; she saw him finish, then put a morsel of dark bread between his lips and bade him chew. She fed him cheese and sausage in this way as well, and then she—still naked herself—helped him don his layers of clothing.

Only once Albert was fed and dressed did Famke pull Nimue’s bloodied chemise over her head. She tugged Albert toward the canvas and put a stick of charcoal in his hand, climbed onto her pillowed platform, and struck the pose. “Now draw me,” she ordered him.

After a moment, Albert began. Hesitant at first, then more sure, he marked the canvas with the line of her nose, then a bit of her shoulders, and her breasts, belly, and legs, through the cobwebby cloth. He consulted his sketches and made a few refinements to the piles of pillows. Last he did her arms and the cascade of hair. Then, having outlined his magnum opus, he threw away his pencil and with a cry raced out into the street.

Famke, shivering, quietly picked up the pencil and put it with his other painting things. She wrapped herself in a blanket and stood before the canvas, trying to see, in the rough lines of black against stark white, the image of herself that would eventually live there.

To her, the space looked nearly empty.

Once the real work got under way, Albert could scarcely tear himself away from his Nimue. He swore that she would hang in the English Royal Academy’s annual exhibition, win him respect and commissions, and convince his father to continue the financial support—if Albert even needed it after his success-to-be. He congratulated himself on having chosen such a quintessentially English subject as Merlin, believing that the familiarity of the myth would help his cause.

He divided the canvas into small spaces a few inches square and took one as each day’s assignment; sometimes he exhausted daylight trying to cover his allotment. Famke thought he was slow because his brushes were so fine that some used only a single hair, but these were part of his way of working and she said nothing about them.

Painting, Albert started at Famke’s fingertips and worked his way slowly downward, spending as much time on the background portion of each square as he did on Famke’s body. No matter what he was rendering, she stood there locked in her dramatic pose, her stillness and exposure reassuring him that he was indeed at work. If he wanted to talk, she listened.

He liked to tell her stories: of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood and their ladies, of the Nordic myths she’d never heard, and of unusual events all over the world. Famke’s interest in Nimue’s lack of hair Down There suggested the tale of John Ruskin, the Brotherhood’s father-figure, who had been divorced because of unexpected difficulty with that unaesthetic region. “He had never seen a real woman without clothes—he had only seen painted ones—and he was ill prepared for it! On his wedding night, he ran from the room in a fit, and they lived together chastely until she sought annulment.” Famke laughed until she fell off her platform.

That story reminded Albert of the Norse myth in which the trickster Loki had stolen Thor’s hammer and cut off the hair of his wife, leaving the thunder god powerless and his wife both lightheaded and angry with her husband. And then he remembered that, just a few years ago, a French matron had received a life sentence for murdering her husband, based largely on the fact that, like any good housewife, she had entered the prices of her murder weapons (shovel, hammer, boar trap) into her account book. Around the same time, an American circus master had marched twenty-one elephants across a New York bridge to test the strength of the steel. Albert dreamed aloud of pictures he might paint from these tales, collected from newspapers and pot shops in his native land. Famke listened hard, though she couldn’t visualize the pictures he described and sometimes the blood puddled so in her limbs that she could barely think, much less translate the stories in her head. She concluded that she would never know much of the world; and so she let her mind go blank and simply posed.

Albert’s conscience was pricked one day when she fainted clear off the platform, disturbing the careful arrangement of pillows and giving herself a large red welt on one leg. After that, he told her to listen for the church bells and to make sure she had a pause every hour. Then, while she stretched, he could clean his brushes, mix more paint, or occasionally make one of the crazed runs through the street that restored balance to the hand that held the brush, discipline to the eye that plotted composition and detail.

Famke’s fall also made him realize how deeply dissatisfied he was with the pillows. They were solid, yellowish-white, soft—not at all the crystal daggers that a scorned nymph would erect around her ravisher. So when he came back from one of his wanderings, he was lugging a chunk of ice. He heaved it onto Famke’s platform and stood admiring it.

“I fished it out of the old harbor,” he said, pushing it a little to the left. “I’ll paint this for today—so you may continue to rest, my dear.” He was as excited as a boy with a new puppy, or a youth with a first love. When he pulled off his gloves, his fingers were purple. It took a long time to warm them enough for work.

“Fanden,” Famke said in a pleasant enough voice. She felt rejected, dejected, but the word relieved her feelings somewhat. Without bothering to hunt for her clothes, she climbed into bed. The cold had tired her out, and she told herself to be glad to have a cozy afternoon. It was nice to have pillows on the bed again.

“Fan’n,” Albert repeated absently as she sank her head in the downy softness. Curled on her side, she watched him gaze deeply into the ice, as into a crystal ball. He mixed several shades of blue-white and began dabbing at the canvas with them, lost in his new idea. Eventually, lulled by the soft brush-brush of his work and the little wet sounds on the palette, Famke fell asleep.

In sleep, her mind flew back to the orphanage. Now she was boiling soap again, as she’d been allowed to do that one time; all was just as before, except that it was Viggo, not the cauldron, that burst into flames. She felt the heat from his body, and she turned around to see the orphanage building was made of ice. Sister Birgit’s eyes filled with water and she was about to say something to Famke, but—

Famke woke when she heard a crash in the street, followed by a curse from the same general area. Albert had thrown the ice block out the window.

“It melted too fast,” he said with a shake of the head. “I couldn’t get the essence down—look, this bit will have to be painted out. I need you now.” Unceremoniously he dragged Famke from the bed and barely let her rub the sleep from her eyes before standing her up on the platform again.

Famke didn’t attempt conversation; she tried not even to think about Albert and his mood. As she stood still for the remaining hour of daylight, she wondered instead what it was that Sister Birgit had wanted to say. Famke was no more superstitious than she was religious, but she felt there was a message in the dream, if only her mind could see it. And she suddenly realized that she missed Birgit; since leaving the farm on Dragør, she had been in no position to turn up at the convent orphanage.

“Left leg bent,” Albert said crisply, and Famke came to attention. She had straightened her leg without knowing it; she’d have to focus on the pose or risk Albert’s wrath. So Famke made her mind a blank.