Читать книгу Accidentals - Susan M. Gaines - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление3

We didn’t, of course, sleep out at the estancia that first time, and it was over a week before we got it together to go back. First, Mom wanted to get her papers in order so she could vote in the upcoming election. This entailed a lot of running around town and waiting in lines at reputedly overstaffed but famously inefficient government offices. Next she wanted to buy a used car, so we could get to the estancia without Juan. And then she insisted that we paint the upstairs bedrooms in Abuela’s house, which hadn’t been done in anyone’s memory but Abuela’s. The car turned out to be easy, thanks to Elsa, who put out word to her many friends and turned up a perfectly serviceable 1988 Toyota pickup. Painting the upstairs was another matter.

“Abuela’s not going to like the color,” I told Elsa. “It’s way too cheerful.” I was driving our new truck and Elsa was riding shotgun, the cans of sunny yellow paint we’d just bought sliding around in the back.

“She’ll like it. She’ll just pretend not to. Take a left there.” Ostensibly, we were just picking up the paint, but Elsa had talked me into stopping at the shopping mall to buy a present for her granddaughter.

“Mom tried to get her to choose, but she was totally uninterested. She says the whole house was painted a few years ago.”

“Thirty years,” Elsa said. “At least.”

“Oh.” I laughed. “That’s a long few years.”

“Juan had the downstairs painted a few years ago. But no one has done anything upstairs since we got married. Since we met, actually, thirty-five years—” A car with a loudspeaker on its roof pulled out of a side street in front of us, Elsa was interrupted by a blast of campaign music.

I shifted into first and inched along behind the flag-bedecked car—bright red, with “Batlle 15” emblazoned across the middle. “What party is that?”

“Colorado. Jorge Batlle’s branch.” Elsa rolled down her window and started singing along, swinging her mass of brown hair back and forth in time with the beat. “Alumbrar el camino, defender la mañana…. ¡juntos! ¡juntos!” The lyrics seemed pointless, but it had a catchy tune and Elsa was clearly enjoying herself—well, Elsa could look like she was enjoying herself when she was cleaning a bathroom. But she wasn’t the only one. It was all rather festive. With the election less than a month away, the whole city was geared up—political graffiti covered every untended wall, banners fluttered from apartment balconies, leafleters stood on corners, and campaign cars cruised the neighborhoods blasting party songs and slogans. Cars passing us in the other direction now honked in appreciation, as if we were part of a wedding procession, while a man walking along the sidewalk with two little kids yelled something mildly derogatory about “Jorge,” and a woman standing in a shop door gave him a thumbs-up sign.

“It’s sort of like Sundays after the soccer games,” I said, “when everyone goes parading around waving the team flags.”

“That’s exactly what Juan says!” Elsa stopped singing, as if I’d caught her indulging some secret childish pleasure. “He complains that people aren’t taking the election seriously.”

“Do Uruguayans take anything more seriously than soccer? At least they’re enthusiastic.”

Elsa laughed and started singing again, reaching across me to honk out the rhythm on the truck horn.

The only politics I’d known in my lifetime was a passive and somewhat desultory, indoor activity—watching TV, listening to the radio, reading the newspaper, maybe a conversation at the dinner table. There might be a few bumper stickers and suburban lawn signs, the occasional billboard, but I’d never seen politics out on the street like this, accompanied by such panache and passion. “Mom told me Rubén is coming all the way from Venezuela just to vote,” I said when Elsa stopped singing.

“He thinks the Frente Amplio has a chance of winning. That’s why he’s coming. Even your cousin Patricia says she’s going to vote Frente. Breaking with family tradition.”

“I take it that’s Colorado?”

“¡Colorado como huevo de ciclista! My father was a Colorado. And my grandfather before him.”

I glanced at Elsa, unsure what she meant by “red as a cyclist’s balls.” Certainly not communist, as the left-wing badge of honor seemed to fall to this Frente Amplio that Rubén and my cousin liked. I supposed it had to do with the history—according to the Enciclopedia uruguaya, the Colorado party started out as a band of gauchos who wore red hatbands and fought with the Blancos, who wore white hatbands. In the early twentieth century, they’d all traded their hatbands for party flags, and their horses, guns, and gaucho knives for cars, songs, and slogans. The Colorados had remained aligned with Montevideans’ interests, and the Blancos with those of the big estancia owners, but I had no idea what that meant for Elsa’s family of small-town shoemakers.

“Jorge Batlle es un flor de tipo,” she said.

A flower of a guy? “You mean Batlle’s gay?”

“Ha! No, mi querido rubito, it means he has a good character. Honest, honorable, straightforward. Here, turn right.”

She directed me down a side street, past a high-rise Sheraton hotel, and into a sunken parking lot. “El Shopping,” as Elsa called the mall, was an imposing stone structure that took up several city blocks and looked more like a fortress than a shopping mall.

“It was built as a prison,” she explained as we stashed the paint in the truck cab, “nearly a century ago. The government closed it in the eighties, and it sat empty for years while everyone debated what to do with it. It had a bad reputation during the dictatorship, and some people wanted to tear it down. Finally, they sold it off, and El Shopping opened a few years ago. They did a marvelous job of remodeling, keeping all the old walls, and the gatehouse and entry.”

On the inside, the place was a dizzying three-level atrium of shops with a floor-to-ceiling stone arch rising like the Arc de Triomphe in the middle.

“Lili refuses to come here,” Elsa said, leading me around the mezzanine. “Says it’s a travesty.” She giggled. “Remember when I visited you in California? I made her take me to that shopping mall near your house almost every day.”

“Valley Fair.” I laughed, remembering how Elsa had fallen in love with our San Jose suburb. “The worst of American culture, according to Mom—malls and processed foods. Though I actually think she had a closet love affair with both. One time I caught her munching on Froot Loops, eating them dry, like candy, while she graded papers.” I looked around. “This place isn’t that bad. Definitely not as ugly as Valley Fair.” It was weirdly grandiose, but not entirely unattractive, with the old stone walls and plenty of outside light from the skylights in the roof.

“It revitalized the neighborhood. Lili complains that the chains put the small neighborhood shops out of business, but we didn’t have that many small shops here. We certainly never had a baby boutique,” she added, steering me into Mi Bebé. My cousin Patricia was coming to visit from Buenos Aires with her two-year-old, who Elsa hadn’t seen in nearly six months. “What do you think?” She held up a yellow jumpsuit for me to admire.

“Nice color. It’s the same as the paint we just bought.”

“It is! Let’s see if Celia notices.” She handed me the jumpsuit and continued flipping through the tiny hangers.

“Do you think she’s glad? I mean, that Mom came back?”

“Celia? Of course she is.”

“And Juan Luis? They argue all the time.”

“Lili should feel honored. The rest of us just get the silent treatment.”

“I guess I thought everyone would be glad to have Mom back.”

I must have sounded worried, though I think I was more puzzled than worried. Elsa stopped shuffling through the hangers and laid her hand on my arm. “Of course we’re happy to have her home, Gabriel. It’s just that no one understands it. Leaving your sweet father. Your lovely house. Her work. It’s like going nowhere, like treading a wide circle and ending up back where you started thirty years ago. What does she have here, after all? The estancia?” She turned back to the rack of clothes and extracted a miniature jean jacket with a pink embroidered bear on the pocket. “Oooh … isn’t it precious? What do you think?”

“Definitely,” I said. “She’ll love it. At least, I’d like it if I were a baby.” Shopping was not exactly my favorite activity, but the combination of Elsa’s habitual joie de vivre and this miniature icon of American fashion was irresistible. “Come on, I’ll buy it,” I said, because she was waffling over the price tag. “And you can get her the jumpsuit.”

“You can’t go spending all your money on presents for Emilia!”

“Why not?” I handed her the jumpsuit and reached for the jacket. “She’s the closest thing I’ll ever have to a niece. And I’m temporarily rich. Mom even wanted me to subsidize her back-to-the-land enterprise.”

Elsa examined my face to make sure I was serious, and then she relinquished the jacket. “I don’t know what she’s going to do out there,” she said as I herded her toward the cash register. “Juan Luis wants to make the estancia lucrative after all these years, but she fights him every step of the way.”

I shrugged. “Mom sees the estancia more as a way of living than a business. She thinks it doesn’t need to be lucrative, just self-sufficient.” Of course, Elsa had already heard this from Mom, just like I had. But Elsa was an innately practical person and none of it sounded at all practical. As far as Elsa was concerned, the estancia wasn’t even the issue—not a justification for Mom’s actions, but rather, a symptom of some general Mom malaise.

“The money from their father isn’t going to last long,” she said as we paid for our purchases. “And neither will your savings, if you keep this up. Can you get that job of yours back?”

“Probably.” I hadn’t even considered it, but I didn’t want to get into a long conversation about my future. “Did I see La Cigale down there? I haven’t had any ice cream since we got here.”

“Yes! Let’s go! I don’t care if you are rich, I can still buy my favorite yanqui his favorite ice cream.”

Mom was probably getting impatient for the paint, but I was enjoying myself, and Elsa kept running into friends and stopping to chat. I ducked into a bookstore and bought myself a bound journal and tin of colored pencils. They didn’t have anything on the local birds, but I thought I might keep a bird diary and sketch what I saw, something I’d gotten good at when I was a kid—I’d started copying the pictures from the Peterson guide when I was about five, and then it got so I could draw live birds from sight, which had impressed Grandpa to no end. I hadn’t done it for years.

We had finally made it to La Cigale and were waiting to order our cones, when Elsa returned to my question about Mom’s homecoming. “Don’t misunderstand,” she said, taking hold of my arm for emphasis. “I missed Lili terribly, probably as much as Celia did. She was only eighteen when she left, and we didn’t see her for years. When she started coming for Christmas with you and Keith, Celia was so happy, we all were—but it was always a relief when she left. You never knew who or what was going to set her off—Keith, Celia, Juan … and then that horrid, destructive sarcasm. Gabriel, I love having Lili home, and I hope it works out at the estancia, if that’s really what she wants. But whoever knows what Lili wants?”

“Certainly not her son,” I said, savoring my first bite of dulce de leche ice cream—the joyful flavor of childhood, of family vacation, of Uruguayan summer—and thinking, paradoxically, of Dad. If Dad had been with us, we would have gone out to La Cigale ten times by now.

“She was always so full of wild ideas,” Elsa said, paying for our cones. “Always stirring things up. It’s what I love, what made her so much fun when we were young—but sometimes she stirs the wrong soup. That was in the eighties, the last years of the dictatorship, everything still uncertain, and here comes Lili, flying in with all her bright California ideas, preaching about ecology and trash recycling. As if a bit of trash was the end of the world, as if we didn’t have other worries, as if we needed more. You were too young to remember, but one Christmas she got irked about something and left the house for two days, just disappeared. Made us all sick with worry, which is probably what she wanted, but you didn’t do that in those days, you just didn’t.”

We walked back to the escalator that ran alongside the Arc de Triomphe, and I listened to my aunt go on about Mom and ate my ice cream as fast as I could, because it was already starting to melt, thick caramelized cream sliding down the sides of the cone and over my fingers, impressing upon me the fluid and unreliable nature of sweet childhood memories. Immigrant, emigrant, inmigrante, emigrante—it all sounded the same, especially in English, but I was beginning to realize just how different those inverse views of the same person could be. Mom had been an American citizen all my life, but I had always been conscious of her as an Uruguayan immigrant—of her accent, her outsider’s take on American culture, her taste in shoes, her mate. It was her identity, a foreignness she cultivated, part of what made her special and exotic, even in California’s Latino communities. Here in Uruguay, however, Lili was an emigrant, someone who had left the country—an identity loaded with so many vectors of remorse, retribution, guilt, and blame, I couldn’t possibly sort it out, even if I wanted to. Which I didn’t.

Abuela, as predicted, was decidedly underwhelmed by the cheerful shades of yellow paint we’d chosen. What we hadn’t predicted was that the house itself would resist our efforts. The walls soaked up the first two coats of paint as if the plaster had turned to sponge, and it took us several days and another trip to the paint store just to do the two bedrooms and the hallway. I began to share Abuela’s ambivalence. But Mom wouldn’t let go of it. Sure, maybe she felt guilty that Abuela and the house had gotten so old and run-down in her absence, but it was more than that, as if painting those rooms was part of laying claim, reestablishing her right to call Abuela “Mamá,” to call the house “home.” She complained that everything took too long, that there were too many interruptions, too many old relatives and childhood friends plopping down at the dining room table and expecting her to prepare a mate and regale them with her stories and wit. It wasn’t really so different in California when I was growing up, despite her complaints that the yanquis were too isolated and enclosed in their houses. I pointed out this inconsistency, of course, but she denied it. She claimed that people were doing what they’d always done when she came to Montevideo, trying to cram years of family gossip and friendship into weeks—that no one would accept she’d come home to stay. She had divested her immigrant identity of thirty years simply by abandoning her adopted country, but moving back to Uruguay did not change her emigrant status. She might be able to repatriate, but she could not undo the fact of having left.

At the estancia, there were no old childhood friends. No ancient aunts or second cousins. No intractable family home, sucking up her energy like a dried-out sponge. No tangles of remorse and guilt, no unappreciative mother. Just green grass and blue sky and a couple of crumbling buildings that responded to every small attention, where even the most jerry-rigged construction was a splendid improvement. And an accommodating, if not quite complicit, son.

We didn’t talk much once we got up there, the truck packed with tools and blankets and food as if for a long camping trip. It was quiet and uneventful, but amiable, the two of us working in parallel, Mom replastering the walls of the house while I dug up a field for planting, a utilitarian line of communication between us that was as uncomplicated as the flat terrain. I’d never worked in Mom’s gardens, except for planting seeds and collecting cherry tomatoes when I was little, but I dutifully followed her tedious, labor-intensive recipe for double-digging seedbeds—though I did insist on using a pick to break the sod first. I enjoyed the work in a perverse way, swinging the pick and shoveling out there under the estancia’s infinite sky until my arms and mind went numb, ducking attacks from the field’s ever-more-outraged-and-brazen resident tero, which I quickly reclassified from exotic creature to pest. But mostly, I was just humoring Mom.

It’s not that I thought there was anything wrong with Mom’s plans for an organic vegetable farm on the estancia. But to hear her talk, the farm wasn’t just a midlife hobby or even a second career. It was a creed, a paradigm for the future, something one had to believe in, like the back-to-the-land movement Dad told me was so popular in California in the seventies—like the commune in Trinity County where my college roommate was born. I found it impossible, in 1999, to believe that a few organic farms in Uruguay, or anywhere for that matter, could obstruct the insidious, global blights of the oncoming century. Would Mom’s rhetoric have made more sense back in the seventies, when she and Dad were young? What if they had moved to the estancia then, when they finished college?

I would have grown up here.

I was in a shoveling daze when this thought occurred to me, and it jerked me to attention the way a dream might jerk you out of sleep in the predawn hours. I leaned on the shovel and looked around at the flat green nowhere place where I might have grown up. Right here.

I tried, briefly, to conjure the versions of myself that might have been, if I’d lived out here with my same eccentric mother and a transplanted not-so-eccentric father. But my daydream immediately encountered problems, not least of which was that the era of flower children and environmentalism in California was an era of dictatorship in Uruguay. Mom had never talked much about it, and I couldn’t imagine it making much difference out here—but still, if I thought about Elsa’s account of Mom’s visits in the eighties and Juan’s attitude toward her environmental concerns, it became clear that it wasn’t just the wrong decade for Mom’s experiment, but, as Juan pointed out, the wrong hemisphere. And Dad—despite his supposedly hippie past and love of our Montevideo vacations, it was hard to imagine him on an estancia in the Uruguayan outback. For that matter, they probably would have sent me to Montevideo for high school, and I would have ended up living with Abuela as a teenager—equally unimaginable. I threw a dirt clod at the tero and returned to my shoveling reality.

It was satisfying to see the seedbeds taking form in that expanse of empty pasture, like doodling in the margins of a blank notebook page, watching the sketches grow denser and more detailed, until they transcended doodlehood and encroached on the blank page with real form and substance. By the time our first visitor showed up in the middle of the week, I had decorated the green pasture with three ten-by-twenty rectangles of chocolate-brown soil. I was more than ready for a diversion, when I heard a motor and saw an approaching puff of dust in the distance. At first I thought it must be Juan, though he’d said he couldn’t come until the weekend, but as I set out across the field to join Mom in greeting him, a double-bed white pickup truck turned up the track and parked in front of the house as if it belonged there.

A lanky, balding man got out and introduced himself as Manuel Caruso, the neighbor who leased the land for his cattle. He looked to be about Juan’s age, and he said he’d known Juan and my grandfather since he was a kid. He’d met Mom as a little girl, but she didn’t remember.

“I was glad to hear Juan’s finally going to do something with this land,” he said when we’d gotten through the introductions.

“Actually, it’s his sister who’s finally doing something with the land,” Mom corrected him, smiling sweetly—a smile that anyone who knew Mom would recognize as sarcastic, but which Caruso apparently took at face value. She resisted remarking on sexist Uruguayan assumptions and maintained a genteel tone as she showed him her work on the house. He recommended a glazier to replace the broken windows, and a skilled quinchador for the thatch roof, and he was generally appreciative of her efforts to make the estancia livable—until we walked over to the vegetable beds I’d prepared and she started talking about her agricultural plans.

“If you want,” Caruso said when she finished explaining, “I can have my worker bring the tractor over and plow a plot for you. You’d have your whole vegetable garden ready in an hour.”

I knew Mom imagined my scrapings in the dirt as something considerably more substantial than a garden, but she just thanked him and told him she preferred to hand dig it. “I don’t like what tractors do to the soil,” she said. “And I want this place to be as sustainable as possible. Renewable energy,” she added, making a show of clasping my growing, but very sore, arm muscle. I rolled my eyes, feeling ridiculous, but it just got worse. She launched into a pedantic explanation of how the tractor mixed the soil layers together, whereas her method of digging left the bacterial life in the sub-layer intact and just broke it up so roots could get through. “You only have to do this once,” she said. “And it leaves the topsoil so soft everything else is a breeze.” She sank the shovel into the bed I’d just finished preparing and lifted out a spadeful of fluffy topsoil to demonstrate.

Caruso listened politely, but I was embarrassed. The guy was an agronomist, not to mention a second- or third-generation estanciero. He ran a huge rice and cattle operation. And here was Mom lecturing him on the benefits of hand cultivation, as if he were going to run home and try it on his thousand hectares. I knew all Mom’s theories about soil building and pest control, but I couldn’t bring myself to join in, couldn’t wax enthusiastic the way one might expect, seeing as how I appeared to be part of her project. I turned aside, gazing back toward the house and our little Toyota pickup, squatting next to Caruso’s double-bed white Chevy like a circus pony next to a workhorse. Everything Mom said made perfect scientific sense, of course. But it was ridiculously out of context.

“It’s kind of like how the truck farmers around Montevideo used to work,” Caruso said, and I turned back to their conversation. “Except they did plow. With horses,” he added, and I wondered if he was mocking her.

“And?” Mom said. “Why no longer?”

“They can’t farm like that on a large scale. Can’t grow enough to compete, especially now, with Mercosur flooding our markets with cheap Brazilian produce. And, of course, some crops are just impossible to cultivate that way. Like rice. Surely your brother knows that.”

I could see Mom wasn’t satisfied with this answer, but the mention of Juan’s yet-to-be-hatched rice plan gave her pause, and Caruso himself showed no inclination to continue the discussion. He declined Mom’s invitation to stay for coffee, and as we walked back to the trucks, he invited us to stop by his house, which was not on the estancia next to us, but up the road toward Lascano. “You’ll have to come for dinner next time my wife is here from Montevideo,” he said, sliding into the cab of his truck. He grinned. “And if you change your mind about plowing that field, just let me know. Be glad to do it.”

“And why,” Mom grumbled as he drove off, “do they think they have to grow on a large scale? Uruguay isn’t exactly India.” But she liked the advice Caruso had given her about the house, and the next morning we drove into Lascano to look for the glazier he’d mentioned.

Lascano reminded me of the forgotten places Dad and I used to pass through in Nevada, on our long summer camping expeditions to Wyoming or Colorado, except now it was our actual destination. I had the sensation that half the town was sitting around in the plaza and café watching us, as if we were the featured entertainment of the week, but Mom didn’t care. She was in her high-energy star mode, talking up the baker and the butcher and the cashier in the market, telling them her plans and making her inquiries, as if she were a bona fide member of the community. We finally found the window guy on a dirt track at the edge of town. Mom told him all about the house, admired his collection of old windows, and talked him into driving out to assess the job the next day. People were certainly friendly, though it was hard to tell if they were charmed by Mom, or curious, or just glad to have the extra business. But by the time we got back to the estancia and had lunch, I myself had tired of humoring her and decided to leave my field to the tero and Mom to her frenetic wall-plastering and go exploring. Alone.

I wanted to climb a hill or a tree and get the lay of the land, but there were no real hills and no trees other than the eucalyptus, which were home to a noisy congregation of lime-green parakeets but completely inaccessible for an unwinged beast like me. I’d never seen parakeets in the wild. They were building a massive nest up there, some sort of collective housing arrangement or bird apartment complex—also something I’d never seen. I watched for a few minutes and then continued on my way, turning at the end of the track to follow a narrow canal, which traversed the fields with no apparent beginning or end. A few curious cows kept pace with me on the other side of the canal, but there were no cars or buildings anywhere in sight, no electric or phone lines.

The grass was literally popping with little yellow finches, and there were two surprisingly intrepid brown partridges pecking at insects in the dirt track along the canal—I’d brought my binoculars and new journal, and I started taking notes and sketching the birds I saw, all of which were unknown to me. I’d left my tin of colored pencils at the house, but I included pointers with the colors labeled, so I could fill them in later. I even added some random descriptive notes, as if I were making my own eccentric field guide. After a while, I veered away from the canal and headed off across the pasture, ducking through a barbed-wire fence and skirting the edge of a field with a bull in it. I spotted one of the brown thrasher-like birds that were so common even Mom knew the name, now perched like a sentinel on top of a mud nest, which itself looked like a basketball perched on a fencepost. Hornero, Mom had called it, an “oven-builder,” and the nest was indeed a little like a clay oven—as I was doing a quick sketch, the bird suddenly slipped around the side and disappeared into a small hole. I added some notes: Thrasher-like behavior, but bill is thrush-like, rufous tail wags up and down. Calls: rapid jackhammer, and a ratcheting sound, like a broken bike derailleur trying to change gears. I moved closer and peeked into the hole, but the nest had a trick entrance, a tunnel with a sharp bend, so I couldn’t see anything.

The topography surprised me again as I came to the top of a billow and had a wide view to the north and east, the landscape simultaneously mundane and exotic, the black glint of what I assumed must be Caruso’s rice fields in the near distance, the old palm trees peppered about, looking even more incongruous than they had by the lagoon where I first saw them. I had no idea where I was going or what I would see, and I felt like a kid again, pretending to be an explorer of the wild. No matter that these grasslands had been grazed by cattle for centuries and the water ran in straight canals and the rice fields probably embodied Mom’s worst nightmares of industrial agriculture—for the moment, everything was, for me, a momentous revelation.

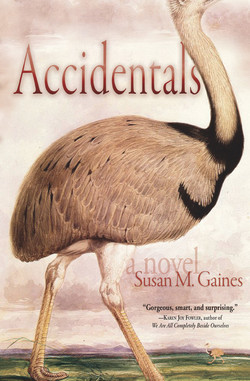

The grass here was well above my calves, and there were no more cows in sight, but scanning with the binoculars, I spied what seemed to be a flock of large ostrich-like birds. There must have been two dozen of them out there, long necks looping down to the ground, heads hidden in the grass. I snuck closer until I could see them with bare eyes, and then I plopped myself down in the grass and sketched one. They looked like cartoon characters—a big blimp of a body on long stick legs, nothing much in the way of tail feathers, and then the long sinewy neck and tiny squashed triangle of a head, all beak and dark eyes, over five feet tall from head to toe. Hangs out in herds like cattle, I noted. At first it looked like they were grazing on the grass, but they were actually picking bugs out of the sod. When I stood up, they all raised their necks in unison, but as I moved closer they started trotting about in random directions, looking so absurd and confused I laughed out loud. I clapped my hands and ran at them, which only caused more chaos—until, as if by magic, they aligned themselves and galloped off like a herd of two-legged deer, the flock completely synchronized as it ran an evasive zigzag. They opened their wings like sails to check momentum and change direction, but they obviously couldn’t fly. I added more details to my sketch and a few more notes: Legs extremely muscular. Incredible wing feathers, but doesn’t fly—

“Are you trying to catch a Ñandú?”

I spun around and blinked up at a man on a horse who, at first glance, might have stepped out of one of the gaucho paintings in the book I’d been reading. Sheepskin saddle, worn brown poncho, leather hat … but he was wearing jeans and balancing a case of Coca-Cola on one knee. His expression was friendly, but quizzical, and I realized I must have looked pretty foolish, running around clapping and laughing, scribbling in a notebook.

“Is that what they’re called?” I said, the color rising in my face. I closed the journal and tucked it under the waistband of my jeans, against my back. “I’m Gabriel Haynes Quiroga,” I added, realizing I’d probably crossed some boundary and was trespassing on his land. “I’m visiting at the Quiroga estancia, helping my mother.”

His name was Santiago Martinez, and he worked for Manuel Caruso and already seemed to know who I was. His face was so weather-beaten I couldn’t tell if he was forty-five or seventy-five. He didn’t seem to be in any hurry, though I imagined the case of Coke must be heavy.

“My daughter lives in Toronto,” he told me.

I guess he thought we would have something in common then, but I knew even less about Toronto than I did about Ñandús. “I think it’s pretty cold there,” I said.

“Oh yes. She hates it! But her husband is an engineer and has a good job there.” He gestured at my binoculars. “Did you see the Carpinchos?”

“The what?”

“Carpinchos. By the canal.”

I shook my head, and he shifted the case of Coke farther up his thigh and indicated that I should follow him.

So much for my lone explorer fantasies, I thought as I hurried along beside my mounted tour guide. I could ignore a cow or two, but humans weren’t supposed to be part of the game. He led me across the fields until we came upon another canal, where he pointed out three oversized rodent-like creatures lazing in the tall grass along the bank. They looked for all the world like guinea pigs—except they were as big as farm pigs.

“Those are wild?” I asked incredulously. We were some twenty yards away, but they looked so tame, I thought they must be someone’s pets.

“Sure. We used to hunt them, but the meat isn’t very good unless you’re really hungry.”

I wanted to move closer, but he was still on his horse and I was afraid he would follow me and scare them away.

“They’re not as slow as they look,” he said. “You get them mad, and they’ll come at you fast, biting like a rabid dog. Guy I know got too close in his canoe once, and they charged and capsized him, tore him up pretty bad.”

“They swim?” They looked too chunky to be good swimmers.

“They like the canals almost as much as the nutria do. You might see one of those along here also, if you keep an eye out, mostly in the water.”

I asked what a nutria was, and he described something that sounded like a giant, aquatic rat but acted like a river otter. He said their pelts were worth a fortune and they’d almost disappeared before regulations were placed on hunting—but they bred like vermin and had made a quick comeback. He then told me a shortcut back to the house and bid goodbye.

I watched him lope off down the canal track, the case of Coke dangling from one hand as if it weighed nothing, and when he was out of sight, I turned my attention back to the Carpinchos. Despite Santiago’s warning, I had the feeling I could walk up and pet them, but as soon as I tried to creep closer, they skittered into the water and paddled away down the canal. Docile-looking, maybe, but definitely not tame. I looked around me at the featureless, green, not-so-empty landscape Mom had chosen for her midlife crisis. It wasn’t the sort of place I’d expect to find large wild animals, but here they were, along with all sorts of exotic wild birds. They adapted, of course, we all adapted. Coyotes on cattle ranches, raccoons in cities, ducks on reservoirs, gulls at dumps. Overgrown guinea pigs in canals, flightless birds in cow pastures … immigrants in foreign lands … And emigrants returning home?

When Juan showed up on Friday night, I began to suspect that the reasons Mom had spent the week plastering walls as if her life, if not the fate of civilization, depended on it were, like everything in the Quiroga family, more complicated than they seemed. She obviously wanted Juan to be impressed by the improvements to the house, but he hardly commented on the new walls, and he pooh-poohed her plan to rethatch the roof, saying only that it was more expensive than tiles and the thatch had to be replaced every five years. He did come prepared to spend the whole weekend, however, and thanked her for cleaning out a bedroom for him. And he was clearly enthusiastic about his own plan to make a map of the estancia—one of the few things he and Mom agreed they needed—and delighted to learn that his nephew was adept with the old surveying rod and theodolite he’d brought along.

There was no way we were going to do a topographic survey of the whole estancia, but Juan did have aerial photos and old survey data, and he figured we could at least do the parts he wanted to develop in the coming year. We worked from dawn to dusk on Saturday, and I began to get a better sense of the place, which still seemed monotonously featureless, the creek and occasional billows notwithstanding.

We were on our way back to the house, resting at the crest of an unusually high billow, when Juan told me that most of the area we’d just covered had been underwater for several months of the year when he was a kid. It was almost dusk, and I was starving, but he laid his equipment down in the grass and lit up a cigarette, in no hurry to get back. We had a panoramic view of the sort that kept surprising me, where I’d suddenly realize I was above everything, even though it all seemed so flat. The grassland tipped slightly toward the northeast, and though we couldn’t have been very high, the horizon looked almost curved. Standing there made me feel like the Little Prince in the illustration where he’s standing on his tiny home planet looking out over its side. Except this planet wasn’t so tiny.

“All this,” Juan said, with a sweep of his arm that took in the horizon and included miles and miles of dry pastureland. “You needed a boat to cross the estancia. The cows were in water up to their hips, horses had a hard time. Some places were so boggy and overgrown you couldn’t get in there any time of year. There’s still a patch like that on our land, down at the end of the creek where you’ve been getting wood. The nutria hunters used to go in there with their canoes, but we never did.”

I thought of the remaining marshes around th San Francisco Bay and Delta, marshes that Grandpa had told me were much more extensive when he was a little boy. But that was at the convergence of two grand rivers. Here, Juan said, the land had been like a giant rain-soaked sponge with water oozing out of every runnel and pore, leaking away in a maze of tiny meandering streams, flowing, if it flowed at all, into the huge lagoon that divided Uruguay from Brazil to the north. I sat down in the grass, watching a pair of ducks winging toward us, wishing I had brought the binoculars.

“The ducks used to be so thick in here the air buzzed when they flew,” Juan said, sitting down next to me. “Your grandfather took me hunting a few times, but I didn’t have much taste for it.”

“What kind of ducks?” I asked as the pair passed out of sight, unidentified.

“I don’t know. All kinds. Fifteen, twenty years ago, there were so many the rice farmers considered them a pest. They’d fly in low over the fields and sheer off all the seed heads like a giant combine, destroy a whole crop in one pass. At least, that’s what people said. I never saw it. The farmers used to put out poison, you’d see piles and piles of dead ducks. It was one of the things your grandfather couldn’t abide, turned him against the rice growers.”

I turned to look at Juan. “Are you going to do that? Poison ducks?”

“Of course not. There aren’t enough left to do any damage anyway. If they ever did.”

I turned back to the tipping horizon and tried to imagine the Little Prince’s planet as a dripping sponge. I asked Juan why it had all dried up.

He told me the ranchers had been building small dams and canals for decades, but that things had speeded up when the government got involved in the seventies and eighties. “It was one of the dictatorship’s screwed-up projects. They built the big dam at India Muerta, and the two main canals. It cost a fortune. And some people lost land to flooding in places where it had never been a problem. But others fared well. Papá was against it, thought the whole plan was stupid, based on something from the last century. But we gained over a hundred hectares of good pastureland. Caruso gained even more—and he was smart. He started with the rice right away, irrigating with water from the canal.” Juan paused. He blew a chain of smoke rings, and we watched them parade off on the wind like little ghost families. “We should have done the same thing,” he said then. “But your grandfather had his head up his ass.” He glanced at me, as if he expected some sort of reaction, but I’d hardly known my grandfather.

“And Mom?” I asked. “What did she think about all this?”

“Professor Quiroga? She was in sunny California raising you. Your mother’s infatuation with the estancia is a recent event,” he added dryly.

A large phalanx of dark-colored wading birds passed above us in a perfect wedge formation, long legs trailing behind them, sickle-shaped bills stretched out in front. Some sort of ibis, I realized as they floated past. They looked sort of prehistoric, the way I imagined pterodactyls must have looked. I’d seen a couple of White-faced Ibis in the Central Valley once, with Grandpa. But this was hundreds. Thousands. The phalanx merged with another, and more rose from the distant fields to join them, each new wedge of birds flowing seamlessly into line to produce a phalanx of birds that must have been tens of thousands strong by the time it faded from view in the northeast. “Incredible,” I breathed, and looked over at Juan, but I couldn’t tell if he’d been watching the impeccably choreographed flight maneuvers playing out in the distance, or if he was staring at the smoke in front of his face.

Grandpa had told me that most of the great California marshes were converted to agricultural land before he was even born, and the rest disappeared with the big government dam projects in the thirties and forties. He’d done his best to save those last remnants for the birds. He said the water projects had been driven by greed and speculation and government corruption. But he’d also conceded that neither San Francisco and Los Angeles nor California’s huge agricultural industry would exist without them.

“So, was it worth it?” I asked Juan.

“What?”

“The drainage project. You said it was screwed up. That it cost a fortune. Did it pay off?”

“The investment? In the larger scheme? Who knows? Who knows where the money came from and where it went. Or even how much they spent. It was the middle of the dictatorship. A few people lost land. And they ran one of the big canals out to the coast, instead of the lagoon, which was idiotic. Ruined the beaches and the fishing, put a couple of hotels out of business. But hell, no one could do anything with all this land before.”

It didn’t look to me like anyone was doing much out there even now, but Juan said I was looking at first-rate pasture and, in the distance, thousands of hectares of good rice cropland. “Twenty years ago, most of this was a no-man’s-land. Lascano was one of the most pitifully backwards towns in the country. No infrastructure whatsoever, no high school, no paved roads … Now it’s thriving.”

I’d be hard put to call Lascano thriving, but Juan was serious.

“Rice did that,” he said. “The highway we drove up on? Wouldn’t be there if people weren’t growing rice up here. And they couldn’t grow rice without the drainage projects.”

The so-called highway wasn’t even paved, but Juan pointed out that it was oiled and solid, wide enough for two trucks to pass. “That road used to be worse than the one to the estancia,” he said, letting out a last blast of smoke rings and grinding his cigarette butt out in the grass. “Used to take half a day to get up here from Rocha.”

“Are you really going to plant rice?”

“Sure. It’s the only sector of the economy that’s growing. A major export. Maybe not a gold mine, but the closest thing we have on offer.” He pushed himself to his feet. “Lili isn’t going to last out here, Gabe. You know that as well as I do.”

I wasn’t so sure. She seemed pretty determined. My volatile and mercurial mother suddenly seemed resolute and steadfast, even content with what she was doing. On Sunday afternoon, I headed back to Montevideo with Juan Luis, leaving her all alone out there. And I wondered: If the whole world were encompassed within this empty sweep of grassland, if a person never had to think about what happened beyond that deceptively tilted horizon—would she, in fact, be happy?