Читать книгу Accidentals - Susan M. Gaines - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление4

When everyone was around, Abuela tended to get overwhelmed and disappear into her room with the radio. But with just the two of us in the house, she was downright gregarious. I offered to clean up her backyard, and she spent most of a morning out there with me. She snipped at the grape arbor—which I was forbidden to prune, though it needed a lot more than snipping—while I raked and mowed the lawn and hacked back the overgrown bushes. She even made attempts to be grandmotherly, preparing lunch for me and regaling me with her special brand of wisdom, trying to educate me. “Do you believe in God?” she asked one afternoon, watching me closely, like I might be tempted to lie to her.

“Not really,” I said, and she nodded approvingly. Then, having deemed me worthy, she took me by the arm and led me around the house, telling me its secrets.

She claimed that my grandfather had designed the beached ship according to symbolic numeric and geometric relationships. The windows in my room weren’t just portholes, they were also, according to Abuela, circles with points in the center. I couldn’t really see the points, physical or figurative, but Abuela shrugged off my objections.

“It was his office,” she reminded me, as if this explained everything.

The granite stairs turned at a certain angle, and the landing at the turn was an equilateral triangle, the stone subtly engraved with a pattern I’d never noticed before, a star inside a circle. Abuela explained something about energy centers and Pythagoras and the Greeks, but the precise nature of the symbolism still eluded me. It was a way of transmitting knowledge, she told me, of passing it on to the selected few who were receptive to it.

“What sort of knowledge?”

“Esotérico. It takes years of study to understand.”

Numbers were significant. There were nine stairs above the landing, then two groups of three making up the stretch down to the living room. “As in the three sides of a triangle,” Abuela said. “The three stages of human life.” I could never tell when Abuela was being cryptic on purpose, to test me, or if she spoke like this—unlinked clauses, nouns without verbs, narrative whittled down to its essence—because she thought my Spanish was so limited it would be easier to understand, or if, in fact, she assumed we shared an empathetic connection that made complete sentences unnecessary, in which case I should be honored. “Youth, manhood, and old age,” she went on. “The three senses. The three kingdoms of nature. The holy trinity.”

“I thought you didn’t believe in that.”

“The Bible contains the greatest allegories in the history of mankind. The Christians just don’t know how to read it.” She peered up at me through her thick glasses. “You have read the Bible, haven’t you?”

“No,” I admitted. “I always figured it was for religious people.” The truth of the matter was, I’d never given it much thought. “Mom and Dad weren’t into that sort of thing.”

“Lili? Lili read the Bible in school. It was part of the literature curriculum. Of course, reading and understanding are not the same.”

We walked through the downstairs rooms, counting windows. “Seven,” Abuela pronounced, as if the number had great portent and weight, an essence beyond the mathematical. “Like the seven planets. The seven vital centers. Seven colors in the rainbow. Seven notes in a musical scale.”

I nodded agreeably, though her number litanies seemed as meaningless to me as a random list of bird species with white wing stripes or yellow heads. But as she heated up the trays of frozen ravioli she’d bought us as a special treat for lunch, Abuela explained that what sounded to me like New Age nonsense—not what I’d expect from my eighty-six-year-old grandmother—was actually based on the ancient teachings of the Masons.

“A lot of important Uruguayans were Masons,” she said. “Your grandfather was widely sought after for his skill with these designs.”

“The Masons? Like Masonic Lodge? Isn’t that some sort of secret male religious society?”

“It’s a philosophical society. Beyond religion.” She extracted the aluminum trays of raviolis from the oven and emptied them onto the plates I’d set out. Somehow the kitchen hadn’t been a priority when my grandfather designed the house. It was a cramped room with an ancient stove and refrigerator, a small sink, a narrow Formica counter and a single rickety stool, everything now yellowed with age. It fit Abuela’s lone eccentric existence like an old pair of jeans, but it was hard to imagine it producing meals for a family of five, in the days before prefab frozen dinners became popular. I rounded up glasses and the grapefruit soda Abuela had bought me, and we carried everything into the dining room.

“It is the duty of the Mason to exercise secrecy and caution in all things,” Abuela told me, once we were seated. “Some kinds of knowledge are too powerful and can be harmful, if we’re not careful. And yes,” she said, smiling slyly, “women were usually excluded. But I found a master who agreed to teach me. I achieved the third grade, and then he stopped and refused to take me higher.” She was clearly proud of this achievement and didn’t seem at all bothered by the fact that her “studies” had been curtailed and she’d been excluded from joining the society. “If I had been properly initiated, I probably wouldn’t tell you all this.” But she seemed to relish telling me, and so I pretended that it all made perfect sense, just like I pretended to prefer the horrid frozen raviolis with cream sauce she got at the supermarket over the fresh ones that were sold for half the price at the little shop down the street. I rather liked the idea of my cool, aloof Abuela telling me secrets.

“Masons have been behind all the world’s liberating revolutions,” Abuela said. “Your George Washington was a Mason. So was Thomas Paine. And Benjamin Franklin. Robespierre. The nation of Uruguay was created by Masons.”

“Artigas?” I asked, thinking of the gaucho founding father I’d been reading about. “Was he a Mason?”

“Artigas,” she said dismissively. “Artigas was a loser. Not to mention a barbarian. It was the Thirty-Three Orientales who fought off the Brazilians, while Artigas was shacked up with some india in Paraguay. Do you know about the Thirty-Three Orientales?”

“The guys who snuck across the river from Buenos Aires and drove the Brazilians out of Montevideo. In 1825,” I added, glad to show off the random bits of knowledge I’d acquired from my book-grazing activities. Artigas’s revolution had gotten rid of the Spaniards and then been hijacked by the Brazilians a few years later, supposedly with the tacit complicity of the Montevidean upper classes. Artigas escaped to Paraguay and faded out of the story, but some of his former captains joined forces with like-minded rural landowners—the Thirty-Three Orientales—and reignited his revolution, winning independence from both Brazil and Argentina. I even remembered a couple of the names, probably because they were also the names of Montevideo’s streets. “Lavalleja,” I said. “Manuel Oribe.”

“They were all Masons,” Abuela said, watching my face, as if she were trying to decide if I was worthy of this information. “All thirty-three of them.”

Abuela was not the most emotive person in the world. She didn’t talk with her hands, like Mom, or with her whole body, like Elsa. But she was a master of the dramatic pause, the lowered voice. “Double three,” she whispered. “Like the thirty-three levels of Masonic learning.” She pushed her plate away—amazingly, she’d finished off her raviolis, while I was still picking at mine—folded her tiny hands on the edge of the table, and went on to tell me that Masons were also behind the Enlightenment, that Voltaire, Diderot, Goethe, and Mozart were Masons. The way Abuela told it, they’d all been following a secret plan for the improvement of society that went back to the beginning of history—a not entirely unattractive concept, though I was a little surprised that she didn’t consider Uruguay’s own Artigas worthy of inclusion. According to the Enciclopedia uruguaya, he’d been a great champion of democracy and equality, appropriating land from the huge colonial estancias and redistributing it as medium-sized tracts to anyone who agreed to fence in their livestock and build a house. It was something like our Homestead Act, though the Enciclopedia didn’t say anything about how it affected the gauchos and the few indigenous groups that hadn’t already been massacred, absorbed, or disenfranchised by the Spaniards.

It was only later that week, when I went out in search of a bird book, that I realized my Enciclopedia uruguaya version of José Gervasio Artigas was just one of many. I went to six bookstores, and the patient proprietor of a dimly lit, labyrinthine used bookstore finally dredged up a single copy of a 1987 edition of Guía para la identificacion de aves de Argentina y Uruguay—but books about Artigas were on every display table. There were dozens of them, just from the past few years, all with a different story. According to the back covers and introductions, Artigas was alternately an ignorant gaucho and paisano, the son of a rich colonial governor, a juvenile delinquent, a bloodthirsty criminal, an inspired social reformer, an Indian lover or an Indian killer, a closet homosexual, a womanizer, a coward, a loser … Abuela’s version was not entirely original—though I suspected she’d modified it to suit her, just like I suspected she’d revised the tenets of numerology and Masonic philosophy.

I could happily have spent another few days hanging out with Abuela, but Mom came for a visit and put an end to our peaceful tête-à-têtes. She just couldn’t seem to hang out with Abuela on Abuela’s terms. The most trivial of rebukes sent her over the edge. When she saw I’d cleaned up the backyard, she immediately started pruning back the grape arbor, and though I told her Abuela had forbidden me to prune it, she went into a funk when Abuela watched over and criticized every cut she made. Mom at the estancia was a much more congenial experience than Mom at Abuela’s house, and I was relieved when she decided to go back out there. She wanted me to help her build a chicken coop, and I was also keen to try out my new field guide, so I went with her. I hadn’t birded seriously since the last Christmas Count I’d done with Grandpa my senior year of high school, and that was in Point Reyes, where I hardly needed a field guide.

We weren’t entirely without experience when it came to chickens. In the third grade, I’d smuggled home two Easter chicks, and they’d grown into the first of a long line of suburban laying hens—and one rooster, which the neighbors, fond of Mom and bribed with gifts of fresh eggs and vegetables, were amazingly tolerant about. Dad had always helped build the chicken coop and its add-ons, but we more or less knew what we were doing—though using the hodgepodge of old posts and planks Mom had collected was a challenge. We spent the better part of a day preparing the site and building the frame, and then I left her working on the walls and set off in search of the boggy patch of land Juan had mentioned.

It was satisfying to be able to name the birds I saw. At the same time, it was something of a letdown to find my personal discoveries had already been described and catalogued. The field guide’s illustrations weren’t very good—my own sketches, I noted with satisfaction, were more lifelike—and Uruguay seemed to have been tacked on as an afterthought, but the descriptions were clear, and the common names were given in both English and Spanish. The parakeets in the eucalyptus were Cotorras, and the stocky flycatcher whose calls woke me up every morning in Montevideo was a Benteveo Común or Great Kiskadee—both names somehow onomatopoeic. It had never occurred to me that the way we hear birdcalls depends on the language in our heads, but I was now filled with bilingual ambiguity whenever I heard the call—kis-ka-deee, one moment, bente-veeeo, the next, and, just to complicate things, Juan described it as “bi-cho-feo,” which translated to “ugly creature.” What had looked to me like yellow-bellied starlings were actually Brown-and-Yellow Marshbirds. The handsome red-crested songbird with the neat white collar that I’d spotted in the brush along the creek was called Cardenal Común, though it was completely unrelated to the iconic red cardinals of the eastern United States.

With the field guide in hand, I was torn between wanting to find Juan’s bog before the sun dropped and an urge to stop and identify everything I heard or glimpsed along the way. There were no litanies of species in my head here, no familiar silhouettes or calls or flight patterns to draw on: I had to wait for a clear view and really truly look, then search the field guide, and then look again, back and forth between guide and bird any number of times before I could put a name to what I saw. The finches bouncing about in the grass like little yellow ping-pong balls must be Mistos—though I wasn’t entirely sure they weren’t Jilguero Dorados. The gregarious cuckoo-like birds in the first clump of bushes I came to were clearly Pirinchos, eight of them crowded together on a branch but facing opposite directions, buffoon-like and disheveled, as if bedhead were a genetic attribute. “Abundant and easy to observe” according to the field guide indicator, though I hadn’t seen them before.

The brush and trees along the creek were alive with unknown songbirds and flycatchers, but I determined to only stop for the ones that showed themselves off, the more obvious ones—some of which I’d already seen and drawn in my notebook. The impressive sparrow with the bandit face and rusty collar was obviously a Chingolo, so ubiquitous it quickly ceased to impress. I saw the blue tanager again, and in the same tree, a lollipop-orange, yellow, and blue one. Celestón. Naranjero. I paused to watch a flycatcher fishing insects from the air, not brown or pale yellow like the flycatchers I knew but a brilliant white. Monjita Blanca. Little white nun? There was nothing nunlike about it. I did a quick sketch, trying to capture the bird’s elegant flirtatiousness, which the field guide didn’t mention. Blinding white, I scribbled beneath it, like bleached granite, fresh snow. Black-eyed, tail dragged in tar.

The creek divided and became more meandering, the brush and trees giving way to clumps of reeds and cattails as it gradually spread into nonexistence. I stopped at the edge of an expanse of swampy, calf-high grass. Above, a group of ibis peeled away from its phalanx and floated down to earth, their plumage flashing iridescent green and purple as they landed in front of me, where I could now identify two species, Cuervillo de Cañada and Cuervillo Cara Pelada. Beyond, just before the reeds seemed to take over entirely, I located the source of a loud, persistent counterpoint of wheezing calls that sounded like a French horn trying to harmonize with a donkey: a pair of huge, corpulent, gray-plumed, vaguely goose-like birds with chicken bills and hatchet-shaped heads. Bright red around the eye and beak, white collar with a black ruff, and an upright, regal demeanor. They were as easy to find in the field guide as in the field, tucked between the flamingos and the ducks, in a family of their own: Chajá, or Southern Screamer. The Spanish onomatopoeic this time, the English descriptive. They looked so heavy and poorly proportioned, it seemed unlikely they could fly, but as I approached, they ran a few loping steps and pushed off. Once airborne, they were transformed, like a fat couple dancing, spiraling upwards as gracefully as the most skillful of raptors, their hoarse screams rising with them, chajá, chajá, heehaw, chajáaaaa … I waited for them to tumble like Icarus back to earth, but they just kept climbing toward the hot sphere of the sun, until they had shrunk to two tiny specks and finally disappeared, their calls fading after them as if they had indeed escaped the earthly pull of gravity.

Earthbound, my own progress was now impeded by a dense, six-foot-high wall of reeds, which was pulsing with sound. There was a chorus of Bay-winged Cowbirds scattered across the top, perched on the tips of the reeds and singing in an assortment of bass, tenor, and soprano voices—their Spanish name was Tordo Músico—but beneath their chorus, in the depths of the reed bed, I could hear a whole symphony of screeching, quacking, and whistling. I tried to enter the forest of reeds, easing myself between the sharp blades and letting my feet sink slowly into the muddy water with each step. As my eyes adjusted to the shadowed light, I spied a flurry of tiny, colorful flycatchers flitting around in the upper reaches, and I wanted to delve farther—but the sun was sinking and the reed bed was so dense and uniform my sense of direction would be nil. Not to mention the swarms of mosquitoes and the fact that my sneakers were flooded with muddy water that was probably full of leeches.

I retreated from the reeds and flipped through the field guide to identify the little flycatchers. They were unmistakable kaleidoscopes of color—yellow breasts, blue faces, flashes of green, red, and black—Tachurí Sietecolores. I hadn’t noted all seven colors, but as I retraced my steps and planned my return, I found myself thinking of Abuela’s number superstitions, wondering if being besieged by Sietecolores was a good portent—and only then remembering that she hadn’t told me exactly what the sevens built into her house by the husband who left her were supposed to signify.

Mom and I finished the chicken coop the next afternoon, and though Juan would probably call it chapucería, I thought it looked pretty deluxe. We drove into Lascano to pick up its occupants, and when we stopped at the Agrocentro I bought myself a pair of rubber boots and a bottle of citronella mosquito repellent. Mom wanted me to buy a hat for the sun, but I hated hats and bought a giant tube of sunblock instead. I spent the next few afternoons exploring the marsh, mapping a route into the reeds one careful step at a time, marking it with bits of Juan’s flagging tape. Juan had told me nutria hunters used to go around the marshes in canoes, but it was hard to imagine navigating even the slimmest of kayaks in there. As it was, I didn’t see a single human until I lost my way on the third day—and found myself, again, thinking of Abuela’s superstitions and premeditated histories.

The reed bed turned out to be just the entrée to a marsh that was more varied and three dimensional—more magical and unfathomable—than any marsh I’d ever known. It was hard to spot the birds among the reeds, but some hundred yards in, I came upon a small open glade that was so crowded with ducks and strange wading birds I felt as if I’d stepped into a natural history museum diorama: A golden-brown bittern standing in the flooded grass, staring up at the heavens as if waiting for a meteor to land in a ball of fire on the point of its bill. A chicken-like bird with the most intense purple-blue plumage I’d ever seen, walking like Jesus across the surface of a water-lily-covered pond. Two huge pink wading birds feeding in the shallows, stirring the water with bills like large wooden spoons. A pair of little reddish-brown ducks floating low in the water near the opposite shore, which was ringed by an impenetrable, half-submerged tangle of brush and trees. Mirasol Grande, Espátula Rosada, Pollona Azul, Pato Fierro…. They paid me no heed, and I stayed there watching and drawing the scene for as long as I could bear the mosquitoes, which were unfazed by the citronella.

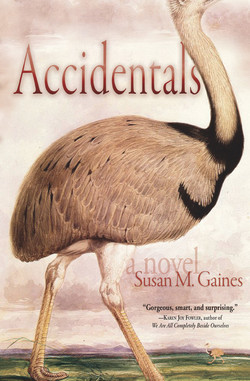

When I was a kid, I kept a “life list” of birds I’d seen for the first time, placing little checkmarks next to their names in the list at the back of my Peterson guide. By high school, the only new additions were accidentals—migrating birds who’d gotten lost, or inexplicable strays who’d wandered away from their normal ranges. If I still kept that list, I could have added more than twenty life birds in just three days. I was following one of them through the reeds—or, rather, trying to get a look at one I had yet to identify—when I got lost. I’d noticed one lonely, insistent voice in the marsh’s evening symphony, a low, hollow-sounding trill, like a bassoon running down a scale and sliding off the end, and then I’d caught a brief glimpse of a fist-sized bird running across the mud. I assumed it was some sort of rail, but it disappeared before I got a good look. I tried to follow its calls, but it led me snaking through the reeds without revealing itself, until I lost both the route I’d marked and my sense of direction. When I finally found my way out, I was on Caruso’s property and the flooded rice fields were aglow with the first colors of the setting sun, the neon-green tips of the seedlings floating in orange flames.

I climbed an embankment, trying to get my bearings, and was surprised to see some familiar Californian characters among the ibis and shorebirds feeding in the fields below—Black-necked Stilt, American Golden Plover, Lesser Yellowlegs … and in the next paddy over, two Hudsonian Godwits and, standing like a lone heron between two tired-looking palm trees, a single representative of Homo sapiens. Young adult female. Slight build. Thin arms, knobby knees. Black hair, pulled into a thick ponytail. Her face was turned away, so I couldn’t see much more, even with the binoculars. She had a canvas bag and a bunch of strange contraptions hanging around her neck. What was she doing out there? She set something into the bag and started making her way toward the levee on the other side of the field, where, I noticed, there was a car parked. Even wading through the mud, picking her way between the plants with all that awkward equipment, she moved with such an arresting mix of competence and sensuality that I wanted to stand there watching her all day. I forced myself to lower the binoculars. This was, after all, a woman I was looking at, not some exotic species of heron.

There wasn’t much daylight left, but I knew where I was now. I could walk along this levee all the way to the canal road or cut across the fields to the house. Instead, I leapt across the irrigation ditch and proceeded down the levee to the next field.

A heron would have been following my every move, watching me through one eye as I neared, preparing its escape. But the woman approached the car and started disentangling herself from her equipment, seemingly oblivious to my presence. When I was about twenty feet away, still trying to decide how to announce myself without startling her, a tero rose from the grass screaming, and she finally looked my way. “Hola,” I called, waving and trying to appear unthreatening, though I felt ridiculous with the hysterical tero threatening to dive-bomb me.

We introduced ourselves politely—Gabriel Haynes, Alejandra Silva, encantada, encantado, pleased to meet you—and I thought how absurd it seemed out there in the middle of the empty countryside. And yet, it was truer to form than I’d ever imagined such a greeting could be, as I was not only pleased, but quite literally encantado, enchanted, under a spell. The sensation was so real, so visceral, it was hard to dismiss, for all that I really wasn’t superstitious: standing there among those rice fields, glorified as they were by the pyrotechnics of a setting sun, I felt an electric jolt of exalted fate.

She stepped back and looked at my binoculars and my muddy rubber boots, and I looked at her bare legs and equally muddy boots and gestured at the canvas bag she was cradling and the pile of equipment she’d deposited on the ground next to the car.

“What are you doing?” we asked as our gazes met, speaking simultaneously and then waiting, simultaneously, for each other to reply, and, finally, laughing.

She tossed back her head and chortled with obvious delight, then fished a small jar out of the bag and held it up. “I’m collecting samples,” she said.

“Of?”

“Mud and water.” She opened the ice chest in the back of the car and set the jar down inside. “It’s a potent brew of microbes,” she added theatrically, “with earthshaking consequences for the future of rice farming.”

I’d assumed she must be a daughter from the Caruso family, and that she would have heard about our reoccupation of the Quiroga estancia. But no, she told me as she transferred jars from the canvas bag to the ice chest, she was a graduate student from the university. They were looking for bacteria that might be helpful in cultivating rice, and Caruso had given permission to do the study on his land. “At the moment, we’re just trying to characterize the interesting microbial communities in these rice fields,” she said, closing the ice chest. She had a raspy Castilian voice that sounded like it came from someone larger and older. Dark green-brown eyes. A dazzling, full-toothed smile. “And you? You don’t sound Uruguayan.”

“I’m from California. My mother is Uruguayan, and she just moved back—”

“You moved here from California?”

“No, no. My mother did. Liliana Quiroga. She and my uncles own the neighboring estancia, and she’s trying to fix it up. I’m just here for the summer. Between jobs.”

“This isn’t exactly Uruguay’s most popular beach resort,” she said, swatting at a mosquito.

“No,” I said. “But it’s pretty good for watching birds.”

“Is that what you’re doing?” She reached up to adjust the elastic band in her hair, her slight figure briefly open to view—small-waisted, small-breasted, round-hipped, and entirely self-assured—as she released and recaptured the mass of black curls. My exalted sense of fate was fast giving way to the more prosaic vertigo of yearning, and I looked away and started telling her about the rail I’d been chasing.

“I didn’t get a good look at it,” I said, “but it was acting like a rail. Lurking around under the reeds, very secretive, never flying. It has this weird call.” I cupped my hands over my mouth and tried to imitate the hollow trill, and then I got self-conscious and fell silent. Usually people glaze over and look for the first escape route when you start talking about birdwatching. I knew this, and yet here I was describing a bird I’d hardly even seen, trying to imitate a call that would have been impossible for even the most adept birdcall impersonator, which I wasn’t.

But Alejandra appeared to be listening attentively. When I broke off, she looked around curiously, as if in search of my elusive rail.

The crazy tero was the only avian representative in easy view, so I offered her the binoculars and pointed out the shorebirds in the next field. She was inexperienced, and I had to tell her how to find the birds and focus, but once she got the band of ibis in view, she took her time, watching them feed.

“They’re eating little crabs,” she said.

“I think they just move their bills around in the water until they bump into something edible, whatever it is. If you look a little to the right and behind them, you’ll see some shorebirds.” I flipped through the field guide for the Spanish names. “The one with the really long legs and black neck is a Tero Real,” I said, though it seemed unfair that the serene and graceful Black-necked Stilt should share a name with the maniacal Tero Común. “The squat little ones with the white eyebrows are Chorlo Pampas. And off to the side there, is a Pitotoy Chico. Those two are migrants,” I added, skimming the field guide entries. “They breed in North America and come all the way down here for the winter. Unbelievable, isn’t it?”

“Yes,” she said, lowering the binoculars and turning to look at me, waiting a beat, and smiling.

I could feel a blush rising in my face, and I reached for the binoculars and turned to watch a small group of ducks fly in and land on the irrigation canal by the road. There was never anything subtle about my blush—my entire face, throat, and ears turned a bright tacky shade of pink. Nicole once told me my blush was endearing, that it made girls trust me, which I didn’t really believe, but it was completely out of my control and I’d long since given up fretting about it. I moved slowly down the levee to get a better look at the ducks. Alejandra had followed me, so I handed her the binoculars again and pointed out some of the field marks, the black cap and pale cheeks and blue bill of the male Pato Capuchino, the extended neck of the Maicero, its cinnamon-colored crown and speckled sides.

“I think I may have seen them out here before,” she said. “But never up close like this. They’re beautiful.”

They were beautiful, but it’s not everyone who would notice it. The Maicero, at first glance, was just a plain brown duck, but its feathers were edged with an ochre color that caught the last bright rays of sun and produced a fine shimmering mosaic of tiny feather shapes in the otherwise dull plumage. There was a lone female Cinnamon Teal, another bird I knew from home, though according to the guide, it was a full-time resident here. Pato Colorado, in Spanish, but there was nothing very colorado about the female, and Alejandra wanted to know how to distinguish it from the other brown ducks. “The form,” I said. “The shape and color of the bill. And when they fly—Keep looking. Watch the wings.” I took a few steps toward the canal and clapped my hands, startling the ducks into flight.

She lost track of them and lowered the binoculars as they rose from the water, but she’d caught the unmistakable sky-blue wing patches as the teal opened her wings.

“So you’re an ornithologist?” she said, turning to look at me. “A student?”

“No, no, it’s just a hobby. I learned as a kid, from my dad’s father. In California I can identify almost anything on sight, sometimes even by call. But my degree was in geography.” I didn’t want her to think I’d spent my life wandering around aimlessly looking at birds. “I work with computer software, doing geographic information systems analysis and mapping for an environmental firm.” Even though I’d quit the job, I figured it sounded respectable. But it was the birds that had caught her fancy.

“You know more than I do,” she said. “And I’m a biologist.” She scanned the fields around us, as if seeing them in a new light. “We’re too specialized. Microbiologists, for example. We never pay attention to what’s going on up there in the higher echelons of the food chain.”

“You should see the birds in the marsh.” I gestured toward the reed bed I’d come out of. “It’s not easy to get into it, but it’s absolutely incredible. If you want, I could take you birding there.”

“I’d like that,” she said, and then she thanked me and made to leave, as if the offer were hypothetical, a mere courtesy.

“When?” I said quickly. “When do you want to go? It should be early morning or late afternoon.” Fate, I realized, was only going to take me so far.

She turned back to look at me, considering, and then she suggested that I meet her the next time she came up to sample. She really did want to go birding, I could see that, but the date she suggested was two weeks away. I wanted to protest that it was too long, suggest we meet in Montevideo on Sunday, when Mom and I went to visit Abuela—but that was too much like asking her on a date and I didn’t want to risk it. Because if she said no, if she disdained the idea of a date with me, what then? So I agreed to the date she suggested, and we left it that I’d meet her there in Caruso’s field at five that afternoon.

I had a friend in college who had a beautiful, well-trained dog, a fluffy white Samoyed that always looked like it was smiling. He claimed that girls who never would have looked twice at him fell in love with his dog at first sight. They’d stop him on the street to ask about it, and if he was lucky, they’d like him by association and go out with him. I’d never imagined using birds to flirt with a woman, didn’t even think of myself as the flirting type. But it occurred to me as I was turning up the track to the house and Alejandra’s car drove past on the canal road, that it was the birds that had captured this woman’s attention. That, and my foreignness, perhaps, the hints of a yanqui accent as I described the distinguishing characteristics of Uruguayan ducks.