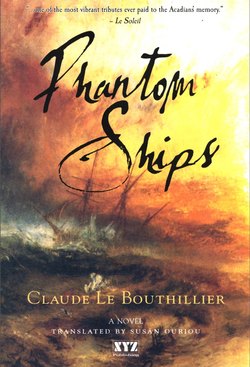

Читать книгу Phantom Ships - Susan Ouriou - Страница 22

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter 8

ОглавлениеI looked for a good location in which to set up residence, but could find nothing more convenient or better than the point of Quebec, called Pointe des Sauvages, and its abundance of walnut trees.

– Champlain, in 1608

Even before the white mans arrival, Quebec1 had been a centre for loud festivities and music for the First Nations. Joseph felt a wave of sheer happiness at the sound of the thousand-pound bell ringing from the cape. Jean-Baptiste and Membertou accompanied him as he walked past the Royal Battery, eleven cannons set up along the river, and entered Place Royale, the marketplace. There were gentlemen wearing tricorn hats, chimneysweeps black with soot, natives wearing gaudy costumes, and, close to Notre-Dame-Des-Victoires Church (built on the foundations of Champlain’s residence), goldsmiths manufacturing religious objects. On a stage in the centre of the square, a theatre troupe was enacting the exploits of the coureurs de bois. The whole place was abustle with the din of the market. Carts clattered down narrow lanes. Drumrolls announced royal proclamations, edicts read out by town criers, which prohibited pretty well everything. Peasants were everywhere, some selling their chickens and vegetables, others carrying barrels of wine on poles slung across their shoulders. In the lanes dotted with yellow spittle, rubbish piled up, as did horse and cow pies, and the stench of fish and excrement floated in the air. But the scent of fresh bread, the fragrance of spices, and more pleasing odours such as the salt air from offshore overpowered the putrid smells. A town crier, wearing a feathered tricorn hat, a blue cloak embroidered with silver lys, and a lace ruffle, rang a bell. He announced the sale of indulgences, then declaimed, “Hear ye, hear ye. That all good people, seigneurs, gentlemen, spread the word, it is forbidden to sell drink to the Indians subject to a fine, imprisonment, or excommunication… Foreigners are prohibited from selling their products without a special permit…”

“Huh,” Joseph observed, “I’ll have to find a way to liquidate my goods.”

They left the marketplace behind and headed in the direction of Le Chien d’Or2 inn on Rue Buade. Joseph had been a regular there when he lived in Quebec. In the smoke-filled room, seated at tables groaning under large pitchers of beer, customers played hoca, cards, or dice. Joseph had trouble recognizing the place.

The decor had changed; the furs hanging on the walls were no longer the same. From behind the counter, the fat owner Philibert, explained, “My partner Gaboury moved to Boston after one too many run-ins with the religious authorities over sales of alcohol.”

Joseph could not hide his disappointment. “Damn rules. Slowly but surely, New France is losing its best men.”

“That’s a fact,” Philibert agreed. “Just last week, a family that refused to convert to Catholicism had to leave for New York.”

Joseph sat off to the side with Jean-Baptiste and Membertou. Tired from the long trip and a bit overwhelmed by all the commotion, he ordered a pitcher of rum tor jean-Baptiste and himself as well as a large glass of maple water for Membertou.

“Fire destroyed Widow Lamothe’s house yesterday,” someone said.

Fire was a constant danger because of poorly cleaned fire-places. Joseph knew all about it; he had seen many a fire during his childhood. At another table, people were complaining about how strict the ecclesiastical authorities were. “It’s to the point where women have to conceal their bodies under blankets,” one coureur de bois spat out. “Because of the damn edicts, they can’t even have long hair or show their shoulders.”

“Those priests see demons everywhere,” his companion added. “Thank God for the forest and the Indian women. With all the rules meant to keep us from living, it’s no wonder Gaboury gave up on the tavern.”

Joseph wished he could have seen his friend, who had always welcomed him like a father when he stopped by for a drink with Emilie, sometimes even after closing hours. All of a sudden, the owner’s son came over to their table and said to Jean-Baptiste, “You’re an Injun, you can’t drink here.”

“The Indians lived here for thousands of years before the white man: I’m not moving.”

Philibert ran over.

“His father comes from Normandy,” Joseph intervened.

The owner burst out laughing. “He’s as black as a crow… Get out before I call the guards… There’s no way I’m losing my permit!”

Two hoca players stood up and tried to grab Jean-Baptiste. He made a fist and laid one of the men out on the table with a single blow. Jean-Baptiste was no longer merely angry: he was furious at being ordered around in his own country.

“My people preached equality when your ancestors were still living like barbarians,” he shouted.

Membertou – on the warpath already – broke a pitcher of rum over one attacker’s head. At that moment, soldiers burst into the tavern, just as the owner charged, armed with a broken bottle. It was time to leave behind the room full of broken chairs and unsheathed knives. Joseph, Jean-Baptiste, and Membertou took advantage of the confusion caused by the soldiers’ arrival to slip out the back door, which gave onto a lane. Jean-Baptiste was purple with rage, incapable of understanding the white men’s scorn. As for Joseph, he didn’t dwell on his emotions. His sole thought was to lose the guards. Luckily, they were able to disappear into a crowd that had gathered nearby around a man, bareheaded, his hands tied, who was crawling on his knees.

“He’s a Huguenot condemned to the whipping post,” a bystander explained.

“Why?” Membertou exclaimed.

“He sold meat on a Friday so he has to pay for his sin at Notre-Dame-Des-Victoires Church.”

“Such powerful clergy…”

“That’s a fact!”

Joseph realized just how far removed he’d been from such practices since his departure for Caraquet’s forests.

* * *

Joseph’s mother worked as a volunteer for the Hàtel Dieu hospitallers, which was where he found her. Full of remorse, as though he had abandoned her, he held her in his arms for a long time. She had aged considerably, and he felt like he was seeing her for the last time. After telling her all about his new life and family, he offered her a coat and hat Angélique had made with her father’s finest silver fox pelts.

“This will keep my old bones warm,” she said as she thanked him.

As for the nuns, they bought all his oysters and pumpkin jam for what Joseph thought was a ridiculously low price: a few silver ecus3 and a crate of apples. He did manage to barter for some silk fabric and ginseng, the plant with medicinal virtues that was being gathered in New France for sale at a good price in China, to take back to Angélique.

* * *

After a restless night spent torn between his life in Caraquet and Quebec, his memories and reality, his need to know more and the need to forget, Joseph decided to see Cristel, Emilie’s younger sister. He hadn’t spoken to her since his departure, back when he was desperately trying to find some clues to his fiancée’s disappearance. He knocked on her door. She threw herself into his arms, as innocent and pure as the Emilie he had loved. They went for a walk on the ramparts by Château St. Louis overlooking the river, and talked at length. Cristel finally made up her mind. “I have something for you,” she said.

She pulled a small package from her coat pocket and handed it to Joseph. He opened it and was rendered speechless by what he found inside: a letter and a portrait of Emilie. His whole body began to tremble.

From Nantes, Emilie had learned that Joseph was still alive, but just as she was getting ready to come home, she received other news from a ship that had stopped off at Ruisseau, news that Joseph had a wife and child. Silently, Joseph reread parts of the letter, “I dont want to spoil your happiness… A rich merchant from Jersey is looking after me… looking after me… after me… slowly I’m regaining the will to live.” Emilie! Her name crashing in on him to the beat of the current beneath the cape: Emilie, a name whose power he could do nothing to neutralize. He fell into what felt like a drunken stupour, as though the air of Ile d’Orléans – or Ile de Bacchus as it was sometimes called because of its vineyards -had been fermented with all the wine on earth. Cristel tried to distract him, “Look at the fires over there on Ile aux Sorciers. That’s the other name for Ile d’Orléans because of all the fires the inhabitants light at night.”

Joseph felt like his brain itself was on fire. For the longest time, he stood on the ramparts contemplating Emilie’s portrait by the light of the fires’ flames. For the longest time, he stood transfixed, caught between the stranglehold of heaven and earth, the river and the cape, as though in a dream. When the distant fires went out, and the drunken stupor evaporated, and the current fell with the receding tide, he knew he had a choice to make.

“I’m dying to go after her,” he confessed.

“You mustn’t, my friend. You’re happy at home with your new family. You will forget her. Emilie still loves you, but she has to follow her destiny now.”

Deep down, he knew Cristel was right. Emilie’s letter only confirmed that fact.

* * *

The Phantom Ship set sail the next day for Acadia and Ruisseau. Jean-Baptiste did not ask Joseph any questions since his culture taught that another’s silence was to be respected. Jean-Baptiste’s thoughts, too, were elsewhere; he was counting the profits from the sale of his cod. As for Membertou, he could feel Joseph’s distress, and it saddened him because the boy had learned to love the man thanks to the strong bonds they had formed during their voyage.