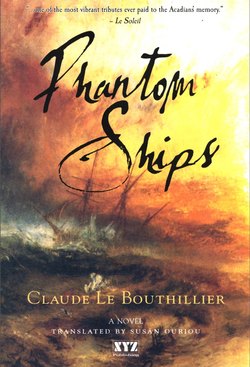

Читать книгу Phantom Ships - Susan Ouriou - Страница 26

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter 9

ОглавлениеVice reigns supreme within the colonies. The governors, district Intendants and ordnance officers sent to govern there are thoroughly convinced that their purpose is none other than to make their fortune and so they behave accordingly, thus ruining trade and serving as a huge obstacle to any progress in the colonies.

– Michel Le Courtois de Surlaville, Vice-Governor of Isle Royale

Josette was born on March 23, 1744 in Ruisseau. A joyful Joseph danced passionately at Pointe-de-Roche, rediscovered the violin, and cared tenderly for Angélique, who had had another long and painful delivery. But, after a few months, he tired of playing nursemaid, and was bitten once more by the travel and adventure bug. His was the age-old story of a man who wants a large family but lacks the patience to look after it! Angélique knew there was no point trying to hold him back. She loved him too much to suffocate him, and the possibility of his earning a few ecus in Louisbourg, where there was a labour shortage, made it easier for her to accept his hasty departure. Membertou’s reaction was another story. Not wanting to let his chagrin show, he took refuge in a world of fantasy, where he daydreamed of the treasure in the cave. As for Jean-Baptiste, his way of dealing with Joseph’s departure was to focus on tending to the schooner, which offered the promise of profitable catches and an abundance of gold Louis. Saint-Jean did not approve of Josephs going, but he did not feel he was in a position to teach Joseph right from wrong, for he was made from the same cloth as Joseph. So Joseph boarded the Licorne, a ship that arrived from Quebec loaded down with provisions for the Louisbourg fortress. On board, he met Nicolas Gauthier, one of Port Royal’s wealthiest merchants, who made clandestine supply trips to Louisbourg. Gauthier operated stores, flour mills, sawmills, and schooners with which he plied his trade as far away as the West Indies.

“People on Isle Royale have nothing but oysters and seafood left to eat,” he told Joseph.

“What happened?”

“The soil there is no good for agriculture. They’re obliged to rely on assistance from Quebec, Port-Royal, or the mother country. Last year, the harvest was bad because of the heat waves, blight, and pests, which did extensive damage to the crops. Then almost all the cured and dried cod was sent to Paris and the West Indies. As for the New England colonies, they can’t supply us with goods because they, too, were hit by the drought.”

“So the English from Boston sell their goods to you?” Joseph exclaimed.

“That surprises you? There’s no point beating about the bush: in peacetime there are more boats from the English colonies in Louisbourg than French ships. In wartime, it’s more of the same,” Gauthier said ironically. “The King of France prohibits trade with the English but, when the French ships don’t bring us what we need, the authorities look the other way and we turn to those who have what we can’t find elsewhere! They make a pretty profit while they’re at it. And, just between you and me, the Boston market is a lot closer anyway,” he explained.

Joseph felt as though he had a great deal to learn about Louisbourg. Gauthier continued, “France did send three supply ships, but one of the ships sank in the ice. What’s more, a number of barrels of flour were underweight, and others were either too damp or contained an assortment of grains. It’s the same thing every year, not that it matters as much when the harvest is good in Canada. When we’re in a bad way, usually the Basques who fish for cod off Isle Royale sell us seabiscuits and pork fat, at outrageous prices, of course. But with a war looming, we don’t know if they’ll be back.”

“If I understand correctly, Louisbourg’s inhabitants are eager for the goods you bring them… What are you transporting?”

“Hundredweights of fine and whole wheat flour, hogsheads of buckwheat and wheat. I also bought livestock in Quebec as well as wine, cider, cognac… I forget how many barrels worth… and other luxuries for the well-to-do: almonds, soap, clothes, sheets, silk goods, shoes. Yet it’s not nearly enough!”

“If Louisbourg is like Quebec, I imagine the authorities make sure their palms are greased in the process.”

“Dear man, it’s worse than that. Some officers are getting rich on the back of the king and the troops. The ordnance officer and the governor are involved, too. Not only are the soldiers’ rations cut back, but tools and material that were supposed to be used to repair the fortress are being sold off in Boston.”

“Can’t you lodge a complaint?”

“What can a lowly soldier or merchant do when faced with an officer who has the government’s protection? It’s true they do sometimes go too far. De Saint-Ovide, the former governor, was accused of fraud and lost his position five years ago because of the rampant corruption and thievery. As for the current governor Du Quesnel, he’s not much better. And the ordnance officer Bigot is worse than all the rest of them put together!”

“What crooks! New France’s future doesn’t look too promising with them at the helm!”

“Especially in view of the Austrian succession, which almost guarantees that France and England will go to war. If that happens, we’ll be fighting in America. Imagine: Port-Royal and Grand’Pré are already under British rule, the Louisbourg fortress is about as solid as a sandcastle, and there are twenty times more English than French in the colonies.”

Joseph had to agree. His thoughts turned to the family he had more or less abandoned in Ruisseau. What would happen to them if war broke out?

The sea was calm that day off Ile Saint-Jean, originally called “Abegweit” by the Mi’kmaq – “land rocked by waves.”

Joseph found Nicolas Gauthier seated on the fore round-house. He looked worried.

“The livestock are dying. If we don’t arrive soon, my trip will have been in vain.”

“We can’t be far from Louisbourg,” Joseph said encouragingly.

“If the winds blow from the north, we’ll be there in a few days… In any case, there’s nothing we can do about it. What are your plans once we’re in Louisbourg?”

“I was told they needed extra hands. So I’ll try my luck.”

“You should sign up as a privateer. If war’s declared, there could be some interesting catches. As early as last summer, the British started trying to intercept supply ships from Acadia, and Le Kinsale, stationed in Canso, managed to capture a Louisbourg ship.”

“I see! In any case, a soldier’s life must be like a form of slavery.”

“I don’t want to discourage you, but they get pretty poor wages and, if they want to earn more, they’re put to work on the fortifications. The officers are in charge of the canteens and liquor. So the soldiers are always in debt. On top of which, they’re poorly fed, often on rotting pork fat rations. As for their clothes, the less said the better; their shirts are made of the cheapest fabric around. Corruption is rampant. The fishermen aren’t any better off. The officers and authorities control the arrival of cargo and fishing gear. The same holds true for merchants, like the Dugas, who own a butcher’s shop. They have to remit part of their profit to the very people who have them in a stranglehold. It’s a sorry life!”

Joseph listened silently, with a sense of shock and concern. He hadn’t come all this way just to turn back now. He had a hard time fathoming the stories of corruption that circulated about the Louisbourg leaders.

“An uprising is what’s needed.”

“A few years ago, the fishermen banded together to send a petition to the minister, to no avail. The soldiers are another matter. I’m afraid that eventually we’re going to see mutiny. Especially since the Swiss soldiers in the Karrer regiment are not attached to France the way the other troops are. There have already been deserters to the English colonies. Following the example of the French Huguenots, the soldiers settle in Boston, Massachusetts, or Virginia.

“I know all about it,” Joseph exclaimed thinking of Gaboury. “We’re losing recruits to the enemy!”

“That’s for sure! As though the enemy weren’t strong enough already.”

* * *

On April 30, 1744, a thick fog shrouded the ship, fog so thick it was impossible to see the fore roundhouse. The ice floes no longer represented a threat, however, and a flock of seagulls circled the ship, a sign that Louisbourg was near. Joseph gave a sigh of relief to think that he would soon be within reach of the fortress at the ends of the earth! On May 1st, when Louisbourg loomed out of the fog, he was dumbstruck. He had never imagined a fortress this big. From the lookout, he gazed at the star-shaped city built on Havre d’anglois and surrounded by ramparts within which more than seven thousand people lived. Soldiers, fishermen, and every other trade as well: carpenters, joiners, limemen, masons, stonecarvers, blacksmiths, locksmiths, bakers… just as in France’s cities by the sea. Outside the ramparts was the fishing village: huts with sod roofs and, nearby, small boats, storehouses, and fish flakes on which the cod was dried. The smell of fish mingled in the air with smoke from the drydock where pitch was being boiled to repair the ships with. The bay, eight fathoms deep, was in the shape of a flattened bottle, and it harboured some sixty ships of various sizes. A forest of masts!

“Louisbourg is at the same time a fortress, a cod fishing post, and a huge trading post where France, Quebec, the West Indies, and New England exchange merchandise,” Gauthier explained. “Its also a hideout for privateers and smugglers! Funny, I dont see any French or Basque fishing fleets. Boats from La Rochelle, Marennes, Saint-Malo, San Juan de Luz, and Sables d’Olonne are usually here earlier than this… I wonder if war has been declared in Europe.”

The docks were crawling with a mottled group of people engaged in a frenzied exchange of merchandise – barrels of pork fat, sacks of grain, hundredweights of dried peas, baskets of cheese from Quebec.

“Its more animated than Quebec’s harbour,” Joseph observed.

Gauthier was busy pointing, explaining, and telling stories. “Look, another ship from Quebec. The barrels on the bridge must be full of cured salmon… The other French ship over there comes from the West Indies with a cargo of rum, sugar, and tobacco. Goodbye food shortages!”

“What about the ships flying a British flag?”

“They come from New England. Boston, New York. A potential market if we play our cards right.”

Joseph looked at the fortress and the Château Saint-Louis, the governor s residence with its magnificent roof made of slate imported from Nantes. In the very centre of the castle, between the governor’s suites and the barracks, stood the clock tower. As the clock chimed eleven o’clock that morning, costumed Mi’kmaq paddled their canoes alongside the Licorne. The commotion grew as the ship drew alongside the dock. Cannon shots boomed. The firepower was such that the whole fortress shook. A troop of soldiers waited on the docks. Joseph disembarked. The flagstones seemed to reel before him, just like the colourful, noisy, variegated crowd. The navy’s drummers formed an honour guard, proudly wearing their red and blue uniforms – jackets, waistcoats, and breeches – and beating on their blue drums decorated with yellow fleurs-de-lys. He also recognized the soldiers of the navy’s Compagnies Franches with their grey-white uniform and blue trim, white jackets and socks, swords on their hip, Tulle musket with its bayonet attached and powder horn attached to the thirty-charge cartridge box.

“See the Swiss soldiers,” Gauthier said pointing them out, “they’re the ones wearing a red jacket with blue sleeves and white buttons. The authorities don’t like them much because most of them aren’t Catholic, and they only obey French sergeants grudgingly.”

“What about the French soldiers?”

“The situation there isn’t much better. Several of them are pretty sickly… They include habitual criminals and orphans recruited from Paris. If war breaks out, sign up as a privateer… It’s more exciting.”

Joseph was engrossed in the spectacle when a few Mi’kmaq and Abnaki joined the troops. On the square, all kinds of languages could be heard in a genuine tower of Babel! The Boston accent, the accent of the settlers come to trade farm products for rum and sugar, the strange speech of the Portuguese fishermen, the accents of tanned fishermen back from fishing off Martinique, or of fishermen used to the cold of the Baye des Chaleurs, or of Acadians from Port-Royal. There were Puritan merchants from Massachusetts, who covered their ears so as not to hear the French captains swearing. More exotic still: Brazilian parrots, African monkeys, and black slaves from the Caribbean. A carousel of colours and sounds, with cannons spewing fire, and a city abustle.