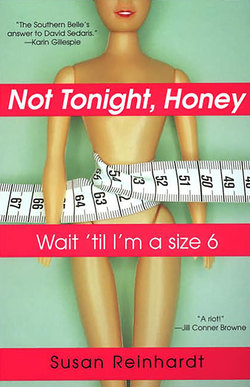

Читать книгу Not Tonight, Honey: Wait 'til I'm A Size 6 - Susan Reinhardt - Страница 14

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Mama’s Bridge Biddies

ОглавлениеAs a child I learned many of life’s lessons eavesdropping on Mama’s bridge club parties. I loved those late nights when the ladies I’d known only as someone’s mother became real people, characters who did more than drive us to school and yell when we didn’t clean our rooms.

They became almost like celebrities on bridge nights and worthy of study from a hidden perch at the top of the stairs. This was where my sister and I camped and learned the secret worlds of grown-up women.

I can close my eyes and still see their animated faces, their lacquered hair and nails, the spirals of smoke that built as evening wore on.

My sister and I gazed as if at a fashion show at their clothes and accessories: bell-bottom pants and midriff tops, pastel shifts, and short dresses, wide patent leather belts, and big wooden beads. We inhaled the strong scent of Maxwell House percolating in a silver pot, the coffee burbling in dark waves against the glass knob and making a sound we could hear three rooms away.

I was twelve or thirteen, and to me, their trilling laughter was like nothing I’d ever heard, this layered and multioctave mirth that seemed rich enough to tell its own story. I wondered why my young friends had never laughed in that way, what could be so funny to these “old” women who had to be way into their thirties. I’d strain to hear their whispers and to smell their Kents and Salems as the tobacco smoke mixed with the perfume de jour—Estee Lauder’s Youth Dew.

On bridge nights after the biddies had finished a couple of Bloody Marys, I heard stories I knew I wasn’t supposed to ever know. Stories of divorce and cheating, stories of gambling, debts, other women, children gone astray, and the message that stuck with me most—that if you get fat and let yourself go to pot, your husband will likely run around on you.

I learned there were times in these other mothers’ lives when they didn’t feel like getting out of bed in the morning and doing the day, putting on makeup and superficial fronts. I learned about nervous breakdowns and people falling apart—how that for a woman of a certain age and circumstance, it was as expected as a man’s midlife crisis. He gets the red convertible and home-wrecking mistress; she gets the feeling of fleeting beauty, lost time, and finds herself in a corner unable to do much more than mutter and wonder how to coax her spirit into seeing reasons to rise each day and put another pound of ground round on the right front burner.

Bridge nights rekindled lots of spirits. And most of Mama’s bridge ladies found comfort and escape through each other, through chocolate, caffeine, nicotine, and moderate intakes of alcohol.

“Proud Mary and Jesus are my drugs,” Mama used to say, speaking of the song by Ike and Tina she liked to dance to on Saturday nights followed by the Sunday mornings she’d plant her long narrow bones on a church pew if her stockings didn’t have a run.

My daddy was in charge on Mama’s bridge nights. He’d let us eat junk food, skip baths, and go to bed with candy in our molars. He made up stories instead of reading them from books and didn’t mind when we climbed onto his back as he galloped through the house on all fours. With him, it was like having a sleepover because he pretended the rules didn’t apply. We ate Swanson’s chicken potpies and drank Cokes instead of milk.

I loved it best though when it was Mama’s turn to host bridge, those nights I never knew what I was going to hear as the blood rushed to my head, upside down in spy position on the staircase, and their voices and stories filled my mind.

These were nights my mother became more than a two-dimensional figure, when she transformed from her alternations of loving and nagging, into an exciting woman living life beyond the borders of her daughters’ whims and husband’s desires.

I’ll never forget the evening I overheard her talking about her first day on the “job” as a volunteer at the local nursing home. She was trying to become a housewife who did charitable works so as to help define her when the working mothers were always asking, “What exactly do you do all day long?” a question that really irked her.

If she’d been a mean-spirited woman, she could have answered honestly, “I cart your children to and from school, to ballet and Girl Scouts, and keep them while you’re working.” But Mama’s not mean-spirited so she kept her mouth shut.

On this night she was on fire with the adrenaline of a hostess who’d mixed the Bloodys with a heavy hand and whose cards were quite possibly the best of the deal. She held her friends spellbound with her words and pacing, and my sister and I were afraid to breathe, scared we’d miss a part of this story.

“I quit volunteering after only two hours on the job,” Mama announced with precise timing and pitch. “I’m telling you, it was something else.” She paused for effect, her nail tapping an ace of diamonds. “The men patients were on one wing and the women on another. The head nurse told me to go fetch the men and wheel them back to their rooms for a nap.”

As Mama told her story, the cards ceased motion. None of the ladies could move, except to drag nicotine or sip drinks.

“After I carted a few of them to their rooms, I went up to this man in a wheelchair with his back facing the wall. I turned that little withery fellow around and Lord have mercy all of a sudden his hand jumped away from his exposed…his shining…penis.”

The laughter reaching the top of the stairs was as explosive as fireworks on the Fourth. “I was mortified,” Mama said. “I ran to tell the head nurse what had just happened, and she said, ‘Oh, well now, he does that all the time.’” Pause. Sip. Tap. “You know what else the nurse said?” The women shook their heads and waited, their eyes huge and expectant. “That nurse had the nerve to laugh at me and ask, ‘Well, do you have one that looks that good at home?’”

By now the bridge ladies were all but rolling on the green carpet, and my sister and I were about to tinkle in our pants. We had never heard our mama saying such things. We didn’t think she knew what a penis was, actually.

“I swannee,” Mama said. “I looked at that nurse with my eyebrows shot up real high and my eyes as wide as they could be and she said, ‘I sure don’t have one at home that looks as good as his.’

“I have to tell y’all, it was a fine-looking thing for his age. It was about the only thing healthy on him.”

I knew the lady telling this story had my mother’s face and voice, but someone else had occupied her body for the night. She was no longer the Baptist Sunday-school-teaching prim and proper etiquette maven. She was a woman set free, the ropes of properness slashed with friendship and chocolate, Chex Mix, and two Bloody Marys. She was a real person with feelings and emotions, not just the lady who made spaghetti and taught me how to set a table, the woman who delegated chores and discipline.

When the cards flapped and fluttered to the table, the coffee mugs clinked in their saucers and ice tinged in glasses, when no husband was around to put a damper on her spirit or children nearby to disappoint her, Mama grew as bold and lively as a fabulous character in a book.

When life got hard she played bridge and sat with seven other women in living rooms all over the small towns in which we lived in Georgia and South Carolina, talking of things I would finally understand after the birth of my own children.

It was soon after my first child arrived, I discovered the world of Mama’s bridge biddies, the feeling of being a nervous wreck and riding the waves of hormone havoc. The more children, pressure, and commitments, the more a nervous breakdown threatened to consume me. It seemed a gracious woman’s due, her rite of midlife passage.

These breakdowns—also known as hissy fits, conniptions, and meltdowns—were as expected as replacing spark plugs and transmission fluid in cars with sixty thousand miles. Every month at bridge, I heard Mama and the ladies mentioning the latest to succumb. And now I was one of them, only I had no bridge club to commiserate with and lighten my load by spreading it around and coating it with Maxwell House, vodka, and chocolate-covered nuts.

I wanted a bridge club, a circle of close friends to share the pain and joys of life with, but there never seemed enough hours in the day for deep and connecting friendships, particularly in the early years of working and motherhood. It was hard enough to find fifteen minutes to cook a real dinner once a week. When I did get together with women, it was with other “mom” friends and we’d end up at play parks and school events, chatting mostly about kids and parenting travails and how one day we would finally fall victim to a good old-fashioned fit or breakdown.

I fantasized about that day often—dreaming of the day I could succumb to my feelings of being dog-tired and overwhelmed. I pictured the uniformed sanity enforcement officers knocking at my door, stethoscopes slung around their necks, clipboards by their sides. I had worked for years to earn a pathetic HMO card and copay, and was ready to put them to use in a serene setting whereby I’d learn guided imagery and hear a voice in a monotone chanting, “Rest, relax, release. Be mindful of every muscle in your body going to sleep.”

It would occur on a day from hell at the office, following a morning from hell at home when no one would get to school on time or have combed hair or brushed teeth. Lunch money would have been forgotten and one of the kids would have said the F word and the other worn a tragically unwashed and mismatched outfit that would have me worried about an imminent visit from the Child Welfare Department. On this particular day from the depths of misery, when the morning sun had forgotten to rise on my side of the bed and everything went downhill from there, I would decide now or never for my nervous breakdown.

“It’s time,” I’d mumble semicoherently at work as I slid under a colleague’s desk. “Call Peace Release at St. Merciful Medical Center. We’re on their plan. I checked an hour ago.” As the sweet coworker dialed the hospital, I would point out the urgent need to run home and get supper on the stove. “My in-laws are coming for dinner and if I wind up in the hopper, they’ll think I just didn’t want to cook. I’ll have the chuck roast and green beans ready and warm for them. The only thing missing will be me and they won’t mind that a bit.

“Tell the sanity patrol to meet me there. I’m already packed. Been packed for three years,” I’d say, crawling to my feet, grabbing my purse and stumbling out the door.

A few hours later they’d turn their white passenger van into the driveway and two men and a woman would hop out, wearing those pinched smiles of concern and carrying papers as if bouquets.

“Mrs. Reinhardt?”

“Yes.”

“We’re here to take you away.”

“Bless your hearts. The pot roast is on, the beans are tender, and I’ve been waiting for this moment for three years.”

“We know how you feel. It’s been crazy the last few days, no pun intended. It’s just that all the moms are suddenly checking in. We got a backlog of working mothers and they can’t do anything at this stage but stutter and drool so you may have to share a room for a while.”

“I’m sure these stutters all mean the same thing, poor dears,” I’d say in all earnestness. “No one at work appreciates them, then they go home and their children hate them and dinner never satisfies anyone. Their husbands are always wanting sex at midnight and yet none of them has said, ‘You’re beautiful’ in five years. You know how it is.”

The woman sanity enforcement officer would nod and I could honestly tell she’d been through several of life’s more cruel wringers. Somebody had long ago forgotten to dry her on the delicate cycle.

“OK. I’m ready,” I’d say, breathing the last gulps of air from my home in the burbs. I’d caught up on enough laundry to find time to work this breakdown into the schedule. I finally clipped everyone’s fingernails and toenails, trimmed and washed their hair, got prescriptions renewed, their dental cleanings in order, and made enough frozen meals to last a month. My husband wouldn’t have to do a thing but sit upright and blink.

Once he discovered eBay he forgot I even lived in the house. And the kids? That’s all taken care of, too. They don’t start back to school for thirty-four more days, so I’d have time for my breakdown with a few days to spare for back-to-school shopping.

This little fantasy was beginning to sound perfect. Just think, three squares a day, no dishes to scrub, scrape, or load. No job to report to. No husband wondering what’s for supper, when is he ever going to get laid again, where’s the remote, and why does his wife wear ratty pajamas when she used to shop at Victoria’s Secret?

I’ll tell everyone good-bye from the unit phone at Peace Release and promise to see them in a few weeks when I come home a brand-new rested, relaxed, and released version of the old self, a woman who promises not to wake up every morning shouting, “Brush your socks! Put on your teeth! Eat your shoes!”

“Ma’am?” the sanity patrol officers will say as they watch me slipping into a stand-up coma, that condition of mothers who zonk but still manage to open jars of Prego.

“Ma’am, where are your children?”

“They’re at Nana’s. I can’t break out of my domestic chains with them staring at me with those big sad eyes and crocodile tears.” Oh, the thought of it would tear me up, a knot clogging my throat as I clutched my chest and felt pain rip my gut like a fist. Oh, my babies. Oh, my wonderful, precious, mean, fighting, mother-hating, messy, loud, obnoxious, brilliant, charming, troublemaking, loudmouthed, adorable, and delightful babies. They were calling to me from Nana’s; I could hear the phone ringing in my heart.

“Uh. Wait,” I’d said to the sanity patrol. “I…um…Let me check the calendar once more.”

Vacation Bible school. Basketball camp. Piano lessons. Beach trip. Allergy shots. Eight special projects due at work plus a mandatory defensive driving school and ethics and diversity training.

I’d bite my thumbnail, knowing that having a nervous breakdown was something I’d have to postpone, at least until I could get my children old enough to babysit themselves. As of now, they require me like teaspoon-size kangaroolets need a mother’s pouch. I’m their cook, shrink, social director, entertainer, doctor, nurse, teacher, preacher—you name it.

“I’m so sorry,” I’d have to say to the men and the lone woman in white. “Could we schedule this thing in ten to twelve years?”

Until then, I’ve come up with a short solution to midlife meltdowns, something my mother taught me years ago every time she cruised the aisles of Kroger and tossed stalks of celery, tomato juice, Tabasco, and Worcestershire into the cart: the mixings for Bloody Mary bridge night.

I learned from those nights about the medicine found in a circle of women, a soothing release of emotion that bandages hurts and rinses the soul. And while I never learned to play bridge, I do read and I joined a book club a couple of years ago. A dear friend who’d lost her precious daughter and her way in life started the group, and the therapy these nights bring is immeasurable.

There are eight to ten of us who meet the first Monday of each month to eat, drink, and discuss everything but the book we were supposed to have read, a book some of us never even open. We call ourselves the “Not Quite Write” book club or the “Read It or Not, Here We Come” crew, and we pass the time as Mama did on bridge nights, talking our way out of stresses and into laughter. We bring delicious hors d’oeuvres and the hostess turns on the charm and her blender.

Humor and friendships heal the strain of our busy lives. The husbands are in charge of the kids, just like the daddies of my mama’s day. They give them too much sugar, too much TV, forget the baths, the teeth, and the thirty minutes of reading before bed.

Sometimes, as the night wears on and we get carried away longer than we anticipated, I’ll see tiny heads peeping around corners. I’ll hear fits of giggles and spot spying little ears listening to things they’ll play back in their minds for a lifetime, lessons learned from a mother’s book club. They’ll see us as real people and not the PTA presidents and room moms. Not the women who yell for them to pick up their clothes and finish their homework.

They will, on those nights, see the other sides of their mothers and realize we’re real people with lives that sometimes jump the boundaries of the expected and venture far away from the carpool pickup lines.

They will remember these lessons forever. Just as I learned them from my own mama’s bridge club.