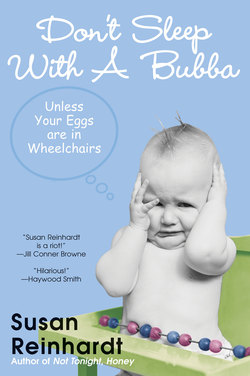

Читать книгу Don't Sleep With A Bubba: Unless Your Eggs Are In Wheelchairs - Susan Reinhardt - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Not Junior League Material

ОглавлениеS ome girls just aren’t Junior League material. We aren’t quite hussies and we aren’t quite saints. Our hearts are pure and loving, but our minds and actions can take quite a few unexpected turns.

We weren’t born with great chances of turning out normal enough to conform to society’s ways and rules, the code of living and wage-earning, the coat of arms and breeding to get us into such circles.

The fact a sorority or two wanted, even requested, my admittance into their Greek system and circles of exclusivity was shocking enough. The fact mine kicked me out three years later for not acting “the part” and being a wild child, was to be expected when you mix girls like me—those with their own ideas about how to behave in college—with a bunch of Izod-wearing, espadrille-footed coeds with bobbed hairdos and clear skin and the Clinique trio of cleanser, toner and moisturizer.

Girls like me had regular old Nozema.

These future Junior Leaguers of America, God love them, and I swear I do, were girls who mainly went to prep schools and finishing schools and whose mothers and fathers were well heeled and, for the most part, either intelligent or boring or both.

I was fortunate enough to have oddball parents: smart, loveable, crazy and selfless. Nothing normal about them.

Both grew up dirt poor but fairly happy. Mama had a kindhearted, but part-time drunken father who one time, on a bender, bought his daughters a pet mule. The three girls rode the mule to death. They came home from school one day and it was lying in the yard on its back, all fours in the air stiff as trees. They also had a goat that ate the clothes drying on the line and anything else it could get hold of.

My daddy had chickens, cows, sheep and a fairly public circumcision at age eight that was the talk of the town. I’m not sure why he didn’t get snipped at birth.

It’s no wonder I turned out crazy—from the time I began shaving off my eyebrows when I was four and wearing wigs in first grade, courtesy of my mother’s odd beautician experimentations, to the times in high school when I’d pull stunts no one else had the nerve to try.

No one will ever forget my swinging the skinned cat from biology lab in front of the teachers’ picture window in the cafeteria as they ate lunch. Or getting tipsy and driving a boyfriend’s black Trans-Am through the practice fields and into the marching band’s formations without so much as denting a tuba.

If one was to pinpoint the moment of genetic differentials, of who gets what and goes where in this world, I believe a big part occurs when sperm meets the egg of two unusual people and thus have no hopes of giving birth to anything other than mutant, though quite precious progeny.

It all began when Mama was 22 and went into labor on November 12, 1961. The doctors knocked her out cold because she was hollering up a storm and scaring the other laboring women and genteel moanings emanating on the ward.

A few hours later they woke Mama up and said, “Here’s your baby girl.”

She was coherent enough to notice that something about the doctor’s face wasn’t right. He wasn’t smiling and seemed chalky. “Looked like Elmer’s was coming out of his pores,” Mama said many years later.

He haltingly handed her the baby (me) in a pink blanket, doing his best to hide my temporarily disfigured and frighteningly ugly face. Mama gasped as if she’d been shown an alien or was a character in one of those sci-fi movies where the mother opens forth and delivers something lizardous.

“Sh-sh-she won’t look like th-this forever,” the doctor stammered. “It’s just a matter of, well…Your p-pelvic bones wouldn’t…you know, and we had to use the forceps and when that didn’t work we resorted to our su-suction method, but unfortunately that failed so we had to call maintenance and b-borrow their Industrial Strength Hoover Mega Vac, but don’t worry, we sterilized all the major attachments and brushes.”

Mama’s mouth opened as if she was going to scream, but being so young, she couldn’t find the words and after wiggling her tongue around and bulging her eyeballs at the doctor in what she hoped was a threatening gesture, told him to get his no-good butt out of there and that if her baby didn’t present any better the next day, she would be Hoovering his own head.

“This isn’t our baby,” she told my dad. “There’s been a big mistake.”

She never told me this story until I was fifteen when she had decided that there was a chance I may not end up tragically unattractive after all.

“Your nose was all the way on the other side of your face, lopped over like it was trying to scoot off your cheek and climb into your ear,” she said, showing me the pictures. “Your head had all these humps and rings around it. Kind of like Saturn but shaped awfully funny, plus you had all this black hair covering your body, and I just wanted the floor to open up and swallow me whole. I’d never seen such an ugly and hairy baby, oh, but we loved you and just prayed you’d get prettier. With your ears being what they were.”

I didn’t say a word as she reached for my hand with her own and squeezed it. “You realize they were the exact size at birth they are right now? A full-grown set of sticky-out Farmer in the Dell ears on an infant. Lord have mercy you were a sight. I thought I’d given birth to a part chimp, and you had one ear that tried to migrate toward the nose and was sort of curling inward, you know, like how a sunflower will tilt its head and lean in toward the sun.”

I instinctively reached up to feel my features, hoping they had settled into their proper place after forty-four years of living.

“Thank the dear Lord they handed you over in that pretty blanket and showing the good side of your face, the side that had a nose on it. Plus, of course, they had the cap on you and must have worked on that ear to get it up under there so we wouldn’t have to see it curling toward your bent nose. Thank goodness the doctor said we could mold your face, so every night your sweet daddy would go to the crib and work on your nose and ears, kneading them like Play-Doh.”

This is exactly how the world began for me.

As for my sister, born two years later, she started out in life being hailed the most beautiful baby to EVER come into the world at Spartanburg General. She had the perfect head, not a mark on her.

When Mama went into labor with Sandy, she wore a beautiful aqua gown and robe set—like something Eva Gabor from Green Acres would wear—and gave birth to the most breathtaking baby girl anyone had ever seen. The doctors and nurses couldn’t take their eyes off this perfect specimen of brand-new human life.

“She is so angelic,” the nurse told Mama as she held her daughter in a pink teddy bear blanket. “Nothing like your first, is she?”

Mama didn’t know what to say. “You remember her?”

The nurse sort of blushed and stared at the floor. “Hard to forget her, but I hear she’s much better or I wouldn’t have brought it up.”

“Oh, yes, she’s gotten so much cuter since you saw her in here. Lots of the fur has rubbed off and her nose is starting to inch over more toward the center of her face, thanks to my husband’s handiwork. He’s a true sculptor, that man.”

The nurse had no manners. “What about those ears she had? Biggest things we’ve ever seen in this hospital. I am not supposed to tell you this. Shhh, our little secret, but we had some plaster and made molds of them because we were absolutely certain no one would believe it when Dr. Milner wrote it up for the American Journal of Abnormalities . We didn’t do photos, knowing you could have sued us. One of her ears was much larger, you know.”

Mama was getting mad and her pain meds were wearing off. “We figure her head will grow and everything will eventually balance out,” she snapped. “I measure them once a week to make sure they’re stabilized and not enlarging, and when we go out, until she gets more hair to cover them, I have handmade bonnets with flaps that do the job. She’s really a cutie-pie nowadays, so go on and give an enema or two and let me be unless you have more pain meds on you. My bottom is throbbing like it’s grown its own heart.”

“I’m sure your firstborn is now pretty as a picture,” the nurse said with a quivering voice. “Oh, but look at this little piece of heaven’s finest you have now. The good Lord sprinkled beauty dust all over her precious features. Those ears are flawless and so cute and tiny.”

Yes, it was true, my newborn sister’s ears lay flat against that lovely round head that needed neither forceps nor the hospital janitor’s Ultra Hoover to pull her 8-pound body from Mama, since I had seasoned her passageway with my brutal birth and donkey ears.

Sister Sandy stayed pretty for the whole week until Mama checked out of the hospital, the entire staff still marveling and cooing. The very next morning, during an afternoon feeding in our little bungalow near the duck-filled lake, Mama walked into the nursery and screamed. Baby Sandy’s genetically perfect ears had sprung from their resting position plastered against her head and shot out like two slices of bologna, huge and perpendicular to her skull. They also grew four inches apiece over the next three weeks, scaring everyone who saw them as they glowed red and were hot to the touch.

To this day we aren’t sure what caused our ear malfunctions, but, needless to say, Sandy had a plastic surgeon correct and beautify her pair. I left mine alone, targets for years of bullying and teasing.

We had no hope for turning out to be anything but crazy. Birth sets the stage, parts the curtains and gives a new human life its first audience. If I tried to pinpoint the exact age that any chance of turning out a regular kid was nipped in the bud, I’d have to say around four years old, when Mama and Daddy signed me up for Kiddie Ranch private kindergarten in Thomson, Georgia, a little Peyton Place town just outside of Augusta where the Masters Tournament is held each year and it meant something if you could get tickets so my daddy got on the list and always had them.

Here’s one big mystery: If your daddy can get tickets to the Masters, why isn’t his daughter asked to join the Junior League? Not that I care. Not that I’m still sore, mind you. Twenty years of therapy and I’m fine, you hear?

Throughout my entire life I’ve both loved and feared and tried daily to please my daddy. I think he was mystified by being the father of a nervous, jittery little child with tics and annoying behaviors that linger to this day.

David Sedaris, one of my author heroes, also suffers from OCD—Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder—and tics. I read it in his book Naked that he licked things: lightbulbs, fixtures, furnishings, and he jerked his head around and rolled his eyeballs up into his skull.

My disorders were checking things a million times and peeing every three to five minutes. This is when the Kiddie Ranch teacher tattled on me and told Mama I tee-teed more than I breathed.

“We went in there with her forty-two times in a single day and, sure enough, I hear it trickling out plain as day,” the teacher said. “Where she’s getting this water I have no idea because all we give them is a Dixie Cup of Kool-Aid. She must be like a camel and store it all in her humps.”

The teacher smiled at her witty remarks, but Mama was all in a tizzy as any mother would be whose kid was a human PVC toilet pipe.

She carted me to a kidney doctor in Augusta, who saw my bare possum (vagina) and I died a thousand humiliated 4-year-old-girl deaths. He prescribed the teensy Valium I took every morning before kindergarten to stop the tics and pee-peeing. I guess it worked. I fell asleep by 10 AM and never awakened until Mama pulled up in her aqua Plymouth, cigarette smoke curling from the windows like kite tails.

There was no way of turning into debutante material with a mama and daddy like ours. I’m not saying that as a bad thing. I love my mama and her sacrifices and selflessness, but her infamous spankings with flyswatters, some of which still had giant Georgia-fly remnants in the webbing, and her constant fears her daughters would become hussies and not get husbands, were terrorizing.

So was her insistence on calling our vaginas “possums.” I know of zero women whose parents refer to their privates as a possum, but ever since I can remember, that’s what my parents have nicknamed my sister’s and my you know whats.

We’d hear things like this throughout our childhoods: “Did you wash your possum?” and “Cover up that possum.” and “I need to take you to Dr. Grayson and see why you keep picking at your possum.”

My parents explained that they chose that euphemism so no one else would catch on.

“It’s not like we can say ‘vagina’ in public, Susan,” Mama said. “Everyone would know exactly what we were talking about, and I’m sure not about to call it a vulgar term. I’ve never cared for the word. It sounds like an emotionally needy body part. It’s too engulfing a term, like a giant maw ready to swallow up the world and cause all kinds of chaos.”

How right she was about that.

So I asked my daddy, who shrugged his shoulders and said, “Your mama names the body parts.”

What else could he say? He’s the poor boy who had a public circumcision at age eight after being told he was going in for a tonsillectomy, and still recalls the embarrassment of all the aunts and his own mother standing over his bed and peeling back the bandages so each could get a good view of the new and improved tallywhacker.

“Looks like he’s going to heal nicely,” an aunt would say, sipping her sweet iced tea as she gazed at daddy’s scabbing penis.

“He’ll have a much easier time with the women when he gets older,” another said, as if my poor daddy’s third-grade self wasn’t even conscious. Fact was, he lay in the bed mortified.

“Women don’t like a smelly region,” one of them whispered loud enough that my dad and his giant ears could hear. “My first husband wasn’t circumcised so you can bet he didn’t get much attention to his needs, shall we say. No one wants to play the ice cream cone game with one of those doggy danglers.”

Lunacy, the sticking-like-a-barnacle kind, is usually handed down many generations. It’s hard to shake it from the DNA and often mutates and regroups into other odd familial behaviors.

Mama, for instance, tended to take everything to the extreme. She meant well and everyone loved her and still does, but that’s her nature and she can’t help it. She was convinced we’d catch diseases and germs, and fall victim to kidnappers, carjackings, knifings, maimings and murder.

“Get sand in your hair and you’ll go bald,” she shouted because she didn’t want to wash our hair every night as we played in the sandbox back when we were living in a house built on a former landfill. “Let a boy stick his fat, wet tongue in your mouth and the next step will take you directly to unwanted pregnancy, teen motherhood and men with El Caminos.”

When my younger sister and I were little, she’d drive us by the county jail and say, “See up there on the second floor where those bars are? That’s where you’ll be if you don’t act nice. They don’t feed prisoners either. Nothing but rutabagas (she knew we hated them) and raw oysters” (another food we abhorred).

About once a month when we were naughty, she’d crank up the green Plymouth wagon with the fake-wood-paneled sides and off we’d go to view the county jail and endure her comments about their diets and lack of food. “Beans and water. On good days.”

The saving grace for most who have mothers on the histrionic side is that they tend to have fathers who balance the equation, daddies who go with the flow, read their newspapers after work, drink a few highballs and ignore most domestic situations.

On Saturdays, when not golfing or grilling, they’ll throw their children a few confidence-boosting bones and play with them outdoors or tell them how great they did during the cheerleading routines on Friday nights.

My daddy was hilarious and crazier than we were. He’d compete with his daughters as if we were his peers, setting up croquet in the yard and getting upset if he didn’t whip our scrawny butts. He once took an old curtain rod, painted it yellow and invented a game called Rolly Bat, which he just HAD to win or he’d sulk a bit. He was the kind of daddy that while quite demanding at times and punitive, was loads of fun, especially when half-loaded.

We grew up on a lake and had a boat parked at the marina where we’d stock the cooler with Millers and take my friends waterskiing when we were teenagers. He told off-color jokes and Mama would say, “They are going to need finishing school, Sam, the things you say to them!”

Maybe this is one reason I didn’t get into the Junior League, though I’m beginning to get over it after two decades’ of affirmations to ward off ghosts of past rejections. With all this in mind, it’s no wonder the Gambrell girls turned out the way we did.

“Remember that time we were in the movies, Susan,” my sister said, “and you whipped around to that bunch of boys we didn’t know and said, ‘Go get us a Coke and box of popcorn’—and they got up and did it?”

Oh, we had our charms and our ways, but normalcy wasn’t one of them. We drew from the DNA Deck and got a couple of jokers, good parents but ones who had their own creative and very different ideas about raising children, daughters in particular.

It all boils down to one thing: some of us are just not Junior League material. I thank the dear Lord every day I’m not nor ever was.