Читать книгу Fake it so Real - Susan Sanford Blades - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

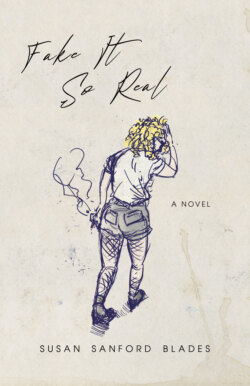

Poseurs

ОглавлениеShepps entered Gwen’s life through the seagull shit–streaked doors of Pluto’s Diner one hot Monday in June of 1983. Braceleted by masking tape, bowed by duffle bag, he was as greasy and limp as an undercooked french fry. He pulled a poster from his bag and asked Gwen if she could spare a bit of wall for his band. It was five minutes ’til close. Gwen had been traipsing around the joint, braless in a pit-stained T-shirt, snarling at customers through her ever-moist Fire Red pout, losing pens in her bleached-blonde witch’s broom for the past eight hours. She flumped her torso over the counter and reached for the sheet Shepps offered.

Lock the door, wouldja? she said. Dorothy’s Rainbow?

At the OAP Hall Friday.

I’m going to that show. To see the Neos.

Red Tide’s playing too.

Too surfy for me. I like it harder. What are you, Raffi? Fred Penner? Singalongs?

Punk rock.

Name isn’t punk.

Wasn’t my idea.

But it’s your band?

Shepps lowered his head and rifled through his bag for an explanation. Gwen had a nose for liars. This guy couldn’t command a sentence, let alone a stage. She pegged him as a wrist-stamper, a hanger-on, occasional tambourine shaker.

We were going to be ska, Shepps said, but my bassist thought punk would get us more chicks.

Does it?

Does for Donny. My bassist. Dude looks like Sid Vicious. Ferries to Seattle every few weeks to give blood for a living and eats nothing but Twizzlers and pussy. Even has track marks.

Hot.

Shepps perched himself on a stool across from Gwen. He was thin as a willow switch, draped in a neon-splattered cotton tee. This guy didn’t give a shit, but in a clueless ten-year-old-boy way.

What’s your poison? Gwen said, and before he could answer she poured him a glass of apple juice. She poured herself a vodka and let him lie to her. He told her he dug the band but wanted to quit. He bemoaned his toad voice. The girls. Every night like a lineup for the dole outside his van—myriad desperate faces with ready palms. Shepps’ lies endeared him to Gwen. This one lied due to the unbearableness of the truth. Nights spent jacking off in a sleeping bag with a broken zipper, judged by the blinking silver eyes of his tambourine. Days spent pointlessly sticking paper to walls, begging the band for a larger role—backup vocals, cowbell. Gwen let him eat her out atop the counter after close, his lips sticky from the apple juice. When she came he leaned his head on her slick thigh and said, You’re delicious.

Is it really your band?

I play bass.

What about Donny?

I play second bass.

Is that necessary?

Not fresh-air necessary.

Every afternoon that week at five minutes ’til close, in traipsed Shepps like a lost puppy. He’d clunk his elbows to the counter, smush his cheeks into his fists, and sheepishly order an apple juice. When he slurped his cup dry he tapped Gwen’s wrist and said, May I eat you out now? Shepps smeared Gwen over every inch of vinyl in the place. Gwen’s boss pulled her into a booth one morning and said, Smell the bench, Gwen. What is that? Bleach? Pancake batter? She dipped her nostrils, shrugged and told him the cook closed the night before.

By Thursday, Gwen hated the way Shepps stared at her through his strands of oiled mullet. With every reverent look, she felt less vindicated in her foul manner, less herself. She hated the way he wriggled his lips around his straw, like an elephant grasping at a peanut. She hated the way he wore his threadbare ripped jeans slung low, teetered between his hips, with no visible bunch of boxer above the waistline. That he allowed his penis free rein between his thighs like a medal she wasn’t privy to. She hated that he never removed his pants, that this was all about her pleasure, his tongue, his fingers. She hated the regularity of his visits. She hated that she anticipated them. And when he didn’t show up that Friday, she hated him.

Friday night, Gwen attended the OAP show flanked by her roommates Mona and Christie. She wanted Shepps to see her, but to not see her seeing him. Mona blew Hubba bubbles and yelled menstrual anxieties into Gwen’s ear. Can you tell I’m wearing a pad? Is there blood showing? I felt a gush. Christie, a Bryan Adams fan, stayed only for Donny, in his Tofino Has Crabs T-shirt and egg white-firm mohawk. She angled herself toward his low-vibrating corner of the stage and gathered all available armpit flesh into the underwire of her bra to create maximum cleavage. Every time Donny tossed his chin toward the crowd, she yanked Gwen’s elbow and whispered, Jesus.

Shepps stood sandwiched between Donny and the drum kit. He wore a blond ringleted wig and tight jeans with an embellished crotch—an allusion to Robert Plant that only accentuated his dissimilarity to the Golden God.

The real leader of the band was Damian Costello. He was not 1983 beautiful. His hair had not made the acquaintance of clippers. His testicles had not been heated to the point of sterility by a pair of tight, acid-washed jeans. His beauty transcended decades. God, how he moved. Skinny and lithe as a garden hose. Johnny Rotten’s death grip on the mic stand without the toothy maw.

After the show, Shepps sidled up to Gwen and invited her and her friends to an after-party in his home—an orange Westfalia he parked at Clover Point. She nodded, eyes fixed on Damian, and despite herself, followed the band. Christie climbed to the Westie’s pop top and dangled a bare leg over the edge at Donny. He took the bait and, seconds later, her bra parachuted to the floor while she produced that second-base gargled moan that encouraged guys to slide into third. The drummer, Ricky, supplied the band with weed, a steady beat, and a throaty guffaw from time to time, but spoke little and the girls therefore considered him sexless. Damian listlessly twanged Mona’s bra strap then excused himself to get some air. Gwen had avoided Shepps all night, kept her head turned at a forty-five degree angle from him, offering only her left ear.

He mumbled into that ear, May I—

Keep Mona company, Gwen said. You can finger her a bit, I won’t mind.

Where are you going?

Gwen opened the sliding door. Mona, I’ve told you about Shepps, right?

Sure, Mona said. Inarticulate, likes to eat pussy?

Gwen slammed the door and spotted Damian, out to sea, knee-deep in kelp. She plunged toward him like a spoon through Jell-O and said, Howdy, then wished she’d opened with something more punk rock like Oi!, then realized that was too effortful and Howdy was so unpunk rock that it, in fact, was punk rock and felt satisfied with herself.

How’d you like the show? Damian didn’t remove his attention from the Olympic range.

The Neos rocked. Red Tide, meh. You sucked.

He spun to face Gwen. Yeah? He tucked a few strands of hair behind his ear and lifted his lips to the left like his face was half frozen.

Yeah. “God Save Pierre Elliott Trudeau”? What is that?

My dad pays for my loft in Chinatown. How about you?

My parents disowned me when I bleached my hair. Gwen scratched her scalp. They still pay my rent.

All those kids at the show—those Oak Bay kids—their moms wipe their asses with hundred dollar bills. And we’re no different. We’re privileged Canadians. Toying with anger. We’re not punk rock.

Dayglos are punk rock.

The Dayglo Abortions are legit badass. So punk they don’t call themselves punk.

I know, Gwen said, then wondered if it might be more punk rock to admit to not know what she pretended to know.

Damian yoinked a sea-salted strand of Gwen’s hair. Why look like Nancy Spungen? She was psychotic.

Would you prefer Nancy Sinatra?

Psychotic’s good. Damian lifted Gwen and splashed and stumbled and shimmied her onto the beach and banged her head on a rock before flopping on top of her. She let him fuck her like a man who, after a day inking paper, had returned home to his aproned wife and slipper-bearing dog, meat loaf firming in the oven. She let him come in five minutes, tuck his limp sea cucumber into his pants, and saunter back to the van because Gwen was twenty-one years old and beautiful boys didn’t need to try.

That July, Damian’s coffee table supported five bags of Cheetos, an ashtray, Gwen’s bare ass, two guitars, seven pipes, Ricky’s spare change, Damian’s bare ass, the soles of Gwen’s shit-kickers, one issue of Verbal Assault, seven tea lights, ten two-sixes of vodka, one burning stick of patchouli, three boogers, one wad of Hubba Bubba and a small, terrifying object.

Gwen pointed to the urine-soaked blue line and said, Do we want this?

Damian bent his head over his guitar, face shrouded by hair, noodled a tune, then peered over the sides of his knees toward the coffee table. Has it been long enough?

The line doesn’t disappear with time.

Baybeh, sang Damian, and Gwen wasn’t sure whether it was a noodling emission or a proclamation of their future.

So?

Do we want a baybeh, sang Damian. He looked up now, not at Gwen, but beyond her, eyes dim and glazed as though scanning a crowd for the hottest, most vulnerable-looking blonde.

So, no?

Do we want to kill a baybeh.

I don’t think I do.

Me neither.

Which one?

The killing one.

Damian put down his guitar. Gwen watched him pull up his saggy socks. Did Johnny Rotten wear socks, and if so, were they from the sale bin at Canadian Tire, greyish white with the elastic gone?

Damian picked up the test. Fuck, yeah. A baby. An experiment. A tiny me. He waved the test around like a conductor’s baton.

It’s not in the stick. Gwen raised her eyebrows and pointed to her stomach.

He tossed the stick onto the coffee table and clenched a fistful of Gwen’s shirt. We’ll get married, he said.

Gwen smiled. She wrapped her hands around his fist.

We won’t tell anyone.

Gwen frowned and dropped her hands.

Except Shepps. He’ll be the ring bearer.

We’ll make him wear a dress.

Sad little flower girl.

Shepps did not wear a dress but he grasped the flowers like a little girl. He brought them himself—lavender and daisies he’d picked on the way to City Hall. They flopped over the side of his fist as though ambling to the tune of his daydreams. I love lavender, Gwen said. Shepps said, I know. Gwen squeezed his free hand. It was clammy, childlike. Damian’s hands were dry as sandpaper, inhuman. We’ve never talked about lavender, Gwen said, and followed Damian into City Hall.

Gwen wore her grade twelve graduation dress—a fuchsia, puff-sleeved, polka-dotted number—because punk rock would soon die but polka dots were forever. Damian wore something Gwen had never seen—low-slung bell-bottoms he’d rolled up tight to conceal their outdated girth and a black suit jacket sized for a child. He looked like a lanky giant dragging two lumpy doughnuts at his ankles. Gwen was about to marry someone whose full spectrum of pants she was not yet acquainted with.

Gwen had not been the sort of little girl who enacted a white wedding with a dandelion tied around her finger and her boy-neighbour’s ketchup chip–powdered lips thrust against her cheek. She spent the idle summer days of her childhood melting her dolls’ plastic faces with a magnifying glass and dodging said boy-neighbour’s arc of urine through the gaps in their shared fence. She was at City Hall to sing the anthem of The Man because Damian was there too and she could not say no to the one person who could say no to her.

Their wedding subverted all weddings. The marriage commissioner wore sweatpants, pilled and thin at the rear. He scratched at his crotch and Gwen was not positive he’d put on underwear. With each question, he glanced at the clock and tamped his growling stomach with a flat palm. Sorry, he said, I haven’t taken lunch. Shepps scattered the lavender at his feet and patted himself in search of gum. Damian offered the commissioner a peanut found in his pocket and he paused the ceremony to crack the shell, chew at the two little legumes and scratch a finger at the bits of thin, rusted skin that clung to his incisors. When the commissioner asked Damian if he undertook to afford Gwen the love of his person etcetera, instead of saying I do, Damian replied: Fuck yeah. And when he signed the registration of marriage, his signature was different from that on his rent cheques. It was lazy, scrawled, defiant. Was he sticking it to The Man or to Gwen?

After the ceremony, Shepps took Gwen and Damian to Pluto’s for a milkshake. Gwen hadn’t seen Shepps in Pluto’s since he’d last kneeled before a booth, clamped between her knees. He ordered two milkshakes and an apple juice. Gwen faced the two men across the table from her in silence. She hadn’t had a conversation of note with either of the two in the few months she’d known them. Shepps was more familiar with her vulva than her mouth. Neither of them knew her favourite colour, though both were impressed with her affinity for the Slits. Gwen scowled into her milkshake, counted the seconds her straw could remain independently erect.

Shepps raised his glass and said, Congrats Dams. His voice trailed off and he bit his lips together as his mouth curved up, retaining his guilty anticipation of the spoils of this union.

Damian tilted his head toward Shepps and rolled his straw between his molars. I feel like we just robbed a bank, he said.

Gwen lifted her straw and sucked a glob of milkshake off the end. What now? she said.

Shepps shuffled into the postnatal ward of the Royal Jubilee Hospital the day after Sara Rae Costello was born. He had always been loose-gaited, but that day he seemed invertebrate. Gwen was without company, baby or makeup.

You had a baby. It was the most punk rock thing Shepps had ever said.

Long time no see, Shepps.

Where’s Dams?

He cut the cord and fucked off.

How’s married life?

The masochist in me loves it.

Shepps smiled and looked at Gwen as if to say You’re delicious, but instead he said, You’re tired. Gwen asked him how he was and he said he was good in a sleepy, elastic tone that made her hate him and everyone who had a life outside her hospital bed. They sat and looked at the walls until a nurse brought in the baby.

Shepps said, She’s beautiful. You look beautiful holding a baby. You look beautiful feeding a baby. And they looked at the baby until he said, I should go.

You don’t have to, Gwen said.

You should rest.

Gwen held her free hand out to him and he filled it with a bouquet of lavender he’d squished into his coat pocket.

I love lavender, she said, but Shepps had already slumped out, led by his forehead and toes.

Sara had a sly smile Gwen loathed, the same smile Damian formed when conjuring alibis. After three years of marriage, Gwen’s nose was full of lies. Sara reserved her smile for moments of mischief. Cheerio-paste paintings on the carpet, feces on the bathroom wall. She sensed Gwen’s frustration and up those lips curled, followed by a plea for Daddy. Daddy received genuine smiles. Giggles, even. Sara bestowed a jowly, Churchillian frown on Gwen.

Gwen dreaded the times Sara was not unconscious. Dread of building blocks, tea parties, the inescapable child’s gaze. Dread of mistakes. Every motion, emotion, utterance potentially lethal. This child weighed too much. At times, she would offer Gwen respite. She’d run a peanut-buttered finger through Gwen’s tangled hair, allow Gwen’s lips to reach the crown of her head, succumb to sleep on Gwen’s downy stomach.

Gwen never felt so observed as when she took Sara out of the apartment. White-haired women fitted in tweed and leather gawked and remarked on the uncomfortable tilt of Sara’s napping head or the discrepancy between the day’s wind speed and the girl’s bare feet. Gwen visited playgroups in search of camaraderie. She was a fuck-up among the blushed and shoulder-padded Oak Bay moms who spoke of carpet swatches, gated tropical vacation rentals and their husbands’ stock portfolios. She was a goody-goody among the spiked and acned Fernwood teen pregnancy crew who pencilled math homework on vomit-crinkled loose-leaf and spoke of upcoming beach fires and not husbands or even boyfriends, but baby-daddies and dealers.

Gwen scorned and admired them all. She wanted to extract cross-sections of each of them—this one’s ability to change a diaper on a gymnasium floor with a stray sock, a safety pin and a muffin wrapper dipped in coffee dregs; that one’s cockleshell lips the light-pink hue of haphazard chapping and kissing—and create an ally, a friend, a community. But she remained catatonic on benches against walls, opening her mouth only to correct Sara’s social blunders.

Damian had no trouble with the girl. Parenting is simpler for the absent. When home, Damian puddled himself over the living room couch, a foundation upon which Sara enacted her day. Last night’s shirt on his back became her doll’s sleeping bag; his pockets, containers for her snacks of marshmallows and chocolate chips. He would join her games as a beached merman or chicken pox victim, nothing that required a plumb spine. Words that were meaningless from Gwen’s lips—words like enough, now, because—were respected commands from Damian. Gwen understood. She also celebrated the reprieves from Damian’s quiet disinterest.

One July night, after Sara’s limbs had softened to curlicues around afghans, bears and mythical creatures, Gwen leaned over her balcony rail like a child in line for a carnival ride, and watched passersby. She was glad she wasn’t them. They were old and crippled. Saddled with groceries and offspring. Fashion victims. Having obvious, pretend fun. Slumping along, zombie-like, as though every crack in the sidewalk were an abyss to traverse.

Gwen yelled, Not playing tonight?

Shepps swayed like a poplar in the breeze. Gwen? He cupped his eyes with his hands and looked up at her. Gwen hadn’t seen Shepps in years. She patted her hair, now long and unbleached, squirrel brown. She held her hands to cover the overripe plum napping under each eye.

Why aren’t you playing tonight? she repeated.

No show tonight.

Then where’s Damian? Gwen dangled her arms over the railing. Why don’t I ever see you?

You don’t come to our gigs.

I’m under house arrest.

Finally caught you?

Why don’t you come up? Gwen’s fingers grasped at the air as though to bail out the sky between them.

Maybe for a minute, Shepps said.

Five minutes, Gwen said. Come in. Talk to me. Lie with me.

Shepps lay with Gwen in her bed, an inert palm to her hip. He told her the truth about his new job pumping at the Esso. She smelled his sweet and sour fingers. He told her about quitting the band. I don’t know if they need two bassists, he said.

Then Shepps lied to her about a girl. Cindy or Sandy or Mindy who worked the coffee stand at the Esso. Filled her uniform well. Snug, he said. She’d been to his van for a beer. He’d undone a few of her buttons, and then a few more. He might take her up island, introduce her to surfing, black bears, his parents.

You don’t even have parents, Gwen said. She pressed her palm to his hand on her hip. Gwen thought about his sickly sweet tongue. How disposable it once was. And how much depended on it now.