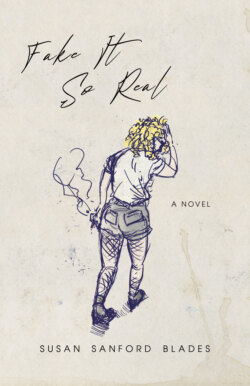

Читать книгу Fake it so Real - Susan Sanford Blades - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Sock Daddy

ОглавлениеGwen’s daughters found their father’s sock the spring after he left, when the nights grew short and the plums grew blossoms. Gwen had been in bed so long it seemed pointless to get out. The girls tumbled over one another around its outskirts in a slithery game of leapfrog. The eldest, Sara, shrieked and giggled, and her baby sister Meg ribbited. Their stubby fingers grasped at the sheets to avoid hardwood-smacked tailbones and closet door handle–driven skulls. Gwen’s limp body swayed like seaweed with each tug from either side of the bed. Then the little fingers released the sheet and there was an audible pause before the girls began to whisper, sinister and insistent. Gwen rolled over to see Sara’s hand encased by a thin, white tube sock, a trail of dust draped from its toe bed like a princess’s ribbon. Sara raised a bony, freckled arm above her head.

I found Daddy, she said.

The sock had lived under Gwen’s bed, ensnared by a warren of dust bunnies, for months, since before Christmas when all was grey and damp. Since her husband’s band played a gig in Vancouver. Since he called from a pay phone and remained silent when she’d said, I want you to want to come home. Since the band’s van put-put-putted to a slump under her window and only the second bassist, Shepps, emerged—a messenger with body shrouded in baggy plaid, face shrouded in greased brown hair, designs on Gwen shrouded in sympathy.

When Shepps buzzed that night, Gwen’s voice scratched through her apartment building’s speaker, Where’s Damian?

I don’t know.

You don’t know?

He took off. Said he’d meet us but didn’t show.

You waited how long?

’Til the last ferry.

Why didn’t you wait longer?

Will you let me up?

Gwen let Shepps in. She didn’t need an answer. The band didn’t wait longer for her husband for the same reason she wouldn’t. Why expect someone to return to a home he’d never truly inhabited?

For a week, the sock dangled from Sara’s hand, a droopy, browning ghost. It held her peanut butter sandwiches, her crayons, her toilet paper. It smacked her baby sister, it swam in the bath. When Gwen stumbled to Sara’s room to tuck her in at night, she’d spy Sara in the glow of her night light with the sock held to her mouth. The sock consumed itself into her fist while she whispered to it.

Why didn’t you come back, Daddy? Did you fall in the ocean? Did you join the mermen?

Gwen assumed Sara would lose interest in the sock. Sara constantly switched favourites with her dolls. A few months earlier, she had loved Maggie with her enviable Goldilocks hair and her comforting imperfections—the red smudge from her lip to her right dimple, the unravelled thread of her left knee. Then Sara’s affections turned to Baby Betty, whose fluffy round head Sara would cup in her armpit. When Betty’s fluff had worn, Sara prized Little Sara, whose hard plastic face made a tinging sound when bumped along the metal balusters of the building’s stairs. But Sock Daddy had not left Sara’s right hand for a full week.

Shepps and his van had haunted the street below Gwen’s window since his return from Vancouver that December. When Gwen needed Cheetos, vodka or rent money, Shepps slept in her bed. When Gwen swore she saw him gawk from the balcony at a jogger’s frenetic cleavage, when he breathed too loudly during Baywatch or ate the last Cheeto, he slept in his van.

At week two, a note accompanied Sara’s bread crusts and the brown bits of apple she’d spat into her lunch kit. It was written in cursive on a cat-shaped Post-it note. Can we talk about the sock? The first word that came to Gwen’s mind was: vague. Then: condescending. Then: who writes in cursive except grade one teachers? Then: well, she is a grade one teacher. Finally: fuck.

The next morning at seven a.m., Gwen looked out her window for Shepps’ floppy form in the van below. His windows were fogged. Who else was in there? Probably that tramp who worked at the 7-Eleven, always sucking on sour candies. Shepps did not have the fortitude to fend off sexual advances borne by minimum-wage desperation and sugared blue tongues. Gwen reminded herself windows could also fog from one person breathing his own sullen van air.

Gwen pulled a boho skirt out of a box of old clothes in her closet. Its whimsical colour scheme would appeal to—or at least distract—a grade one teacher. The skirt last graced her form seven years ago, the summer she met Damian. When her lips were thick and red and had never uttered words like betrayal or baby wipe. But she could not force the skirt’s gasping mouth to zip. Gwen settled for worn jeans, holed in unfashionable areas—hips, crotch, cuffs—and a crop top which, if she held her breath, was almost appropriate. This was how good mothers dressed. A good mother puts her children’s needs above her own appearance.

Gwen and the girls paraded out of the apartment, their teeth gummed with cereal crumbs, their hands milk-sticky. Sara smeared the sock’s wide-open jaw along the stairwell’s peeling wallpaper. Once outside, Gwen smacked a palm to the window of Shepps’ van and pressed the bridge of her nose to the glass. No sour-candy girl, only stretched-out Shepps, alone and there, always there. Shepps shifted and turned to face Gwen. She stepped back, guilty of voyeurism and care, and stumbled over Meg behind her.

Goddamnit, Meg. Always at my feet.

Shepps poked his head out the van’s window. Where you going?

Sissy school, said Meg. She latched five chubby fingers onto Gwen’s back pocket.

A bit early?

Meeting with the teacher. Gwen twitched her head toward Sara, who squirmed the sock into Meg’s brown curls and made monsterly eating noises, Ump. Ump. Ump.

Shepps gave Gwen that look the bank teller gives when you’re overdrawn. Smug pity.

Meg giggled and patted both palms atop her head in unison. Stop, Sock Daddy, stop.

Need a ride? Shepps rubbed his eyes.

We don’t need anything.

Want a ride?

You should probably go back to sleep.

I’m offering, Gwen.

I don’t need your pity.

It’s not pity, it’s a van.

We’re fine, Gwen said.

Why can’t we get a ride? Sock Daddy doesn’t like walking. Sara tilted the sock’s head downward. Her fingers had gathered its fabric into a tight-lipped pout with puffs of thinned, grey cheeks, where the pads of Damian’s feet once roamed.

Sock Daddy can’t always have what he wants, Gwen said.

Miss Howe sat in a miniature chair across from Gwen, who sat atop the “Explore and Discover” table beside a tub of dry rice. Meg lay sprawled face down on the classroom floor at Gwen’s feet. She sealed her lips around a pile of pencil shavings and puffed her cheeks with air. Sara kneeled at Meg’s head, growled and nipped at her with the sock.

Meg, gross, Gwen said.

Sara slid the sock under Meg’s mouth and said, Meggie don’t. It’s germy.

It’s quite natural for a child to form an attachment to an inanimate object, Miss Howe said. But lately Sara’s been a little... Miss Howe held her open palm toward Sara.

Dog-like?

More like...

Violent?

Miss Howe turned her head away from where Sara and Meg pawed at one another on the floor. She opened her eyes wide and mouthed the word nefarious.

Fairyish?

Miss Howe cupped her hands, leaned toward Gwen, and repeated herself.

Gwen wiped the lipstick from her mouth with the back of her hand. Her father left us a few months ago. It’s his sock, she said.

Miss Howe brought hand to heart.

I can’t take it away from her.

Of course not.

She’s got a grip on that thing.

Well, I wouldn’t suggest...

What do you mean, nefarious?

Miss Howe tapped at her collarbone with the fingers of one hand, a fluttering half butterfly. Some of the children—

Meg yanked on the end of the sock. Sara raised the sock above Meg’s head and hissed, then beaked at Meg’s face with it like an angry, off-white goose. Meg held the backs of her hands to her face and swatted up a tornado of Sara’s long brown hair with her palms.

Girls, Gwen shrieked, then continued in faux calm. That’s not how we treat our sisters.

Does she do this at home? Miss Howe said.

Out the window, children congregated in maniacal ball-hurling, stick-wielding herds. Little stockbrokers in anticipation of their mayhem-cueing bell. Gwen didn’t know if Sara did this at home. At home, Gwen lived from bubble bath to bed. Everything in between was a vodka-smeared blur.

He was in a punk band, Gwen said. They had this big gig in Vancouver and then he just...

Mmm hmm. Miss Howe nodded.

Stayed.

Miss Howe nodded.

There, I mean.

Do you have support?

Not here.

Anyone to help?

Not that he was ever around much anyway.

Your parents?

Gwen flapped her lips. My parents? Nope.

That man who brings Sara to and from school?

Shepps? He’s the second bassist.

I’m sorry?

In the band.

Hmm? Oh the—Sara’s father’s.

Meg squeezed a bit of Gwen’s jeans in each hand and pulled herself to her knees. Her floor-swirled curls carpeted Gwen’s lap.

Gwen raked Meg’s curls with her fingers. What about Shepps?

Miss Howe patted Meg’s head. I want to ensure there’s support for you and the girls.

He’s around. For now.

Meg pulled at the neck of Gwen’s shirt and climbed atop her lap. Sara slithered the sock up Gwen’s leg like a boa constrictor. She lifted its mouth level with Gwen’s face, opened her hand inside and whispered, Sock Daddy doesn’t like you.

Gwen swatted at the sock. Stop it, Sara.

Sara turned the sock hand to face her own eyes and asked, Sock Daddy, why don’t you like Mommy?

She’s smelly, the sock told Sara in a gravelly voice.

Gwen stood and dropped Meg to her bottom on the floor. I’m done, she said. We’re out. Have a good day at school, Sara.

She’s smeeeeeeelly. Sara slid to her back on the floor. She waved the sock hand above her in a half windmill, a malevolent rhythmic gymnastics routine.

Gwen grabbed at Meg’s hand, which she flopped out of reach.

She’s smelly and she doesn’t brush her teeth, the sock said to Miss Howe. Miss Howe reached toward the sock and it attempted to swallow her hand whole, boa constrictor style. Miss Howe tittered and pocketed her hand.

Get. Up. Meg. Now. Gwen pulled at Meg’s wrist and dragged her by her diapered bottom out of the classroom and into the hall. Once away from adult supervision, Gwen wrapped an arm around Meg’s waist, picked her up and got the fuck out of there. Once they passed the schoolyard, Gwen dropped Meg to the sidewalk and towed her home by the wrist, crushing sections of sidewalk one step at a time. Meg’s feet stumbled at double time to keep up.

After school that day, Sara and Shepps entered the apartment, a bag of groceries dangling from the sock’s mouth. The sock opened its maw and dropped the bag to the carpet. Sara opened her own mouth, stuck out her tongue and panted like a dog.

Sock Daddy brought chips and bananas and squishy white bread, she said.

Gwen and Meg were sifting through the remains of Sara’s Halloween candy on the living room’s patchy carpet. Sunflower seeds, raisins, black licorice. Not worth the effort to chew.

Bread, Meg exclaimed, both hands above her head.

Maybe Shepps’ll make you peanut butter and jam, Gwen said.

Shepps complied. Sara, you hungry?

Sock Daddy wants sammich.

Sara lifted her off-white right hand and yapped her fingers open and closed. The sock had stretched as a result of its verbosity, each of Sara’s fingers now fit into a grey oval at the sock’s toes and the sock’s heel sat up like a dorsal fin at Sara’s wrist.

Sara, that’s enough, Gwen said.

What? Sara said, sock hand dangled at her side, sock slouched at her wrist and suspended from her fingers like it didn’t care if it hung on or fell to the floor.

Talking with the sock. It’s annoying.

It’s not me, Mommy. It’s Sock Daddy.

Gwen got off the couch and lunged at Sara. She grabbed the end of the sock and dug in with her fingernails. Give me the sock, she said.

No, Mommy. Sara sheltered the sock under her shirt.

Shepps, help me, Gwen snarled.

Can I have the sock? Shepps said.

No. You don’t like Sock Daddy.

Shepps shrugged and wiped a drip of sweat off his forehead with a plaid-covered wrist. Sock Daddy’s alright, he said.

Sara pulled the sock out from under her shirt. She turned its fisted head to face Gwen. Youuu, the sock said, You don’t like Sock Daddy. The sock mouthed a slice of bread and Sara stomped to her bedroom.

That night, Gwen retreated to the bath. She closed her eyes, her access to the outside world, and drifted underwater. She resurfaced to find Shepps unbuttoning his jeans above her. Pants off, Shepps grazed Gwen’s fingers with his own.

Did I say you could come in?

Shepps’ fingers froze. I’ll give you privacy, he said.

I’m kidding. Gwen threw bubbles at Shepps. Don’t take me so seriously.

Shepps tugged at his shirt and said nothing. Damian would’ve said, You’re such a bitch most of the time how do I know when you’re kidding. Damian would’ve ripped his jeans off and thrown them at Gwen so hard the zipper would bite her cheek. Then he would’ve grabbed her by the ear and not kissed her so much as sucked her out of herself through the mouth. But Shepps stood silently and waited for cues. How to be, how to please.

Gwen lifted her fingers and wrapped them around Shepps’. Don’t ask, she said. Do what you want.

Shepps stepped into the bath and kneeled in front of Gwen, placed an arm around her. He lifted her to him and mouthed a nipple. He nosed her neck and she let her head fall back, hit the tub wall.

Sorry.

Don’t be.

Shepps wedged a wet palm between Gwen’s head and the wall. He leaned in and kissed her mouth, dank and unbrushed. She fisted a handful of his slick hair, pinched at the roots, and held his face close to hers.

I want you to hurt me, Gwen said.

Shepps stared, wide-eyed.

Smash my head against the wall.

I can’t.

Pull my hair.

Shepps shook his head. He sat down, cross-legged in the tub, his hand still cradling Gwen’s head. I can’t do that, he said. I love you.

Gwen sat up and released her head from Shepps’ protection. She drew her knees to her face, rested a cheek on them and looked at Shepps, hunched over himself amid the bubbles.

You don’t love me, Gwen said. You don’t want to make me happy.

From the hall, through the inch of opened bathroom door, an off-white triangle whispered, You want to be miserable.

Shepps pulled the door open, with more force than he’d offer a strand of Gwen’s hair, to reveal Sara on the floor. Eyes closed, breath heavy, right arm lowering from the elbow like a spring-loaded lever.

When Sara first formed words, only Damian could get her to talk. Her first word was Da. She didn’t bother uniting her lips to form an m until past age one. Damian called her Jellybean. He made her Froot Loop necklaces and licorice tiaras. He’d skip with her to the 7-Eleven for sugar sticks and cigarettes and then he’d float away at dusk to screech and twang and screw until he decided to cross their threshold again. For Sara, as for any other clueless girl, that was enough.

Sara only opened her mouth now to act as a medium for the sock. She sat tight-lipped and dour, lifting her right hand every now and then to let the sock pontificate. She’d jump Shepps’ checker piece and say, Sock Daddy is suffocating here, or stop, mid-shoe Velcroing, to ask, Where’s Sock Daddy’s yellow pick?

Her lunch kit was littered with notes, all of which Gwen ignored. A Post-it cat stated: We need to discuss the sock. An inspirational duckling declared: The sock is becoming a problem. A ripped scrap of loose-leaf pleaded: Would you consider removing it?

Gwen kept Sara home on extended sick leave. First chicken pox, then measles, mumps, tuberculosis. To the school secretary, Shepps explained that Gwen was anti-vaccination. Oops, he said.

Sara would not let anyone near the right side of her body. The sock was a soggy goo that had not touched towel for weeks. What it had touched: bathwater, soap, shampoo, feces, urine, boogers, chocolate bars, Cheetos. It was a cornucopia of colours and textures. It attracted all manner of dust, crumbs and bug carcasses. Sara left a dribble of filth everywhere she and her right arm went.

I worry about her health, Shepps said. He pushed a hair chunk out of his eyes but it slid back across his greasy forehead to its original position.

Gwen was nested in bed with a bottle of vodka: Shepps, behind her, attempted a soup spoon but came out wooden. Meg lay with her shoulders at their feet, her head dangled off the edge of the bed. Her little legs flopped onto Gwen and Shepps’ bums and her clumsy fingers plucked at their toes.

It’s not so bad, Gwen said. I’m used to it now.

What about school?

We’ve only scraped the surface of childhood disease.

She doesn’t even talk. Shepps raked his pasty fingers from Gwen’s knee to hip, exfoliating her thigh with his crusty plaid cuff.

Ow. Do you ever wash that thing?

Shepps held cuff to face. Red plaid embellished with peanut butter, apricot jam, mayonnaise, egg yolk.

I haven’t been to the laundromat in a while, he said.

There’s a laundry room here, you know.

You’ve never shown me.

Figure it out. I’m out of clean underwear.

Sure. Shepps slugged himself away from Gwen. He stood up, then slumped toward a pile of soiled undergarments.

I didn’t mean right now.

I have to go.

What do you mean?

To the Esso. I have a job.

Gwen levitated her head an inch from the bed.

You need to be here, she reminded him.

We need to pay rent.

This isn’t even your place.

I want to help you, Gwen. But—

I don’t need your help.

I’ll leave if you want.

I never asked you to stay.

That night Gwen bathed Meg and Sara together. Meg attached a few of Gwen’s stray hairs to the shampoo bottle and played mermaids with it. The sock was the enchanted white eel the mermaid rode on. Sara poked two fingers out of holes in the sock’s toe bed, like cartoonish, bugged-out eyes. Gwen sloshed her hands through the water to create the tsunami required to advance their storyline.

Run for cover, Sara squealed. To the high cliffs of Mount Soaperest!

Gwen watched her two girls in the tub. How much space there was without Shepps. How uncluttered. How long would he be gone? How long would the inch of milk in the carton last? Could she get her old job back at the diner? The one she had seven years ago when she met Shepps and Damian, with the red lips and the purposefully scruffy hair and the tight-waisted skirts. She looked down her front. Lumpy. Could she go out in public at all?

Gwen tucked Sara in with genuine affection. And, with genuine affection, said, We need to get rid of the sock.

The sock hid under Sara’s covers. Sara flapped one ear and then the other to her pillow. A firm no. Gwen sat beside Sara on her bed. She imagined Sara’s little fingers pulling every thread of that sock into itself until there was nothing left.

Gwen stood up and said, Daddy doesn’t want to come back.

Once Sara fell asleep, Gwen stood in her doorway and watched her torso rise and fall. The sock covered Sara’s arm, bent above her head like a hanger. Gwen stepped into the room, to the foot of Sara’s bed. Sara’s breath stopped for a second, then resumed, slow and steady. Gwen kneeled on all fours and crawled to the side of Sara’s bed. Sara rolled toward her. The sock arm rose, beaked through the air toward Gwen, and landed level with her face.

Grimy piece of shit, Gwen said to the sock. Sara’s fingers twiddled inside of it. Gwen lay her head next to its face. How could you do this to me? Gwen whisper-screamed, through a clenched jaw, Fuck. You. She rested her forehead on the sock and cried. Sara snored. Gwen shook. Then she bit at a loose section of sock. Sara’s arm lay flaccid. Gwen held the sock in her mouth, pulled it off Sara’s arm. It hung from Gwen’s mouth. She breathed through it, drooled like a rabid dog. She looked at Sara’s right arm, bare and vulnerable.

Gwen crawled out of Sara’s room, panting. She dropped the sock to the floor and used it to wipe the saliva from her mouth. She wanted to rip it to shreds, pin it to the wall, wash it, feed it, eat it. She wanted to put it right back on Sara’s arm.

Gwen shuffled to the bathroom, closed the door and turned on the light. The room was too bright, all of its contents—the bathing pink elephant on the wall, the grey soap scraps, the jar of Q-tips—exposed. Gwen lit a candle and turned off the light. She stared at herself in the mirror. She rolled her head to accentuate the shadows that fell from the hard angles of her face. Stuck out her tongue. Pulled her hair back from her face.

Dirty old sock, she said.

She put Damian’s sock on her right hand. She yanked up until she felt her fingertips rebel at its periphery, an uneasy coating. She gathered the toe bed in her fist and raised it to the mirror.

You want to be miserable, the sock said. You asked for this.

Gwen sat on the counter and leaned against the wall. She pressed her socked palm to her nose. She bit at her socked wrist. She bit harder until she cried out, stuffed her mouth with fisted sock and smacked her head against the wall. The sock withdrew from her mouth, but stuck to her dry gums as her arm lowered, shed like a snake’s skin. The sock hung from her lips and dangled over the candle’s flame. Gwen tilted her head, back and forth over the flame until the end of the sock caught fire. It burned and curled and crept toward her lips. The smell of burnt polyester filled the bathroom. This is it. Gwen pulled the sock from her lips and dropped it to the sink. The end. But she couldn’t. She turned on the cold water and swirled the sock in its pool of filth. She wrung it out and placed that burn-holed, ragged, crust-edged, damp thing back on her arm. The sock slid up her shirt, wet and slow like a slug. It tugged at her nipples and slithered between her breasts up against her throat. Gwen exhaled through her teeth and bottom lip. The sock smelled of rain-washed sidewalk vomit and burnt rubber. It yanked her head from side to side then choked her left wrist and pulled it toward the fork in her thighs. Gwen dropped her right leg to the floor, pressed the crown of her head to the wall, wrapped the toes of her left foot around counter’s edge. She spread for the sock. She arched her back and rocked her hips until the faucet bit into her left hip. And the sock—wet and persistent.

You miss the way I made you feel.

Gwen awoke in bed, alone save for the sock now stuck to her forearm. No starfished Meg, no sliver of Shepps, apologetically teetered at the far edge of the mattress. Gwen sprang her torso erect, elbowed the windowsill. Shepps’ van still sagged at the curb. She breathed out the ball of panic from her stomach. She breathed in, breathed out, stared at the stagnant van. A viscous goo glurped up her throat. That shadowed patch of asphalt was a slow and certain asphyxiation.

Mommy, open jam, Meg yelled from the kitchen. This, followed by a plop and a clink.

Me open all by yourself, said Meg.

Fuck, Gwen said into her pillow.

Meg’s chubby legs encircled a pile of apricot jam on the kitchen floor. She dipped in chunks of squishy white bread, wiped them onto her cheeks and into her mouth.

Great, Meg. Now we have no jam.

No jam.

Gwen fingered and licked an apricot chunk.

No Sissy, said Meg.

What?

No Sissy.

What do you mean?

Meg pointed toward the hall. Sissy gone, she repeated.

Sara was not in her room. Her covers trailed off her bed from one dragging point. Gwen looked toward the apartment door. It was open a crack. Closet door, open. Sara’s raincoat, gone. Gumboots, gone.

Gwen grabbed Meg’s raincoat and a sweater long enough to cover her own granny-pantied bottom. Come on, Meg, she said.

I eat jam.

We need to find Sara.

Meg rose, plodded every appendage into the jam pile, and waddled over. Gwen scanned the stairwell for Sara, between the balusters, the window wells, under dislodged swaths of carpet. She looked for a nest of light-brown hair, a protrusion of pink rubber.

Outside the building, Gwen and Meg approached Shepps’ van. The roof was down. He hadn’t set up the loft bed. He hadn’t slept there. Gwen lobbed a rotten banana peel from the pocket of her sweater at the van’s side window. Meg laughed and threw bits of gravel and grass, pompoms and plastic beads from her pockets toward the van.

Gwen heaved Meg onto her back and paced the building’s property. Surely Sara wouldn’t stray farther. They combed blades of grass, planted themselves next to tree trunks, and scoured mobiles of branches with their fingers and eyes. Meg’s hair was a tangle of cherry blossoms and fir needles. Gwen was a sweatered hunchback with a rattily cloaked crotch. She fell to her knees and plopped Meg to the ground.

I can’t breathe, said Gwen. My ribs.

Meg poked at Gwen’s ribs.

Where the hell is your sister?

Gwen curled into a boulder on the grass. Meg climbed atop the boulder, swirled her apricot-jammed palm into Gwen’s hair. Gwen breathed what air existed between her knees and the earth. Surely Sara wouldn’t stray farther.

Sissy, Meg said. Sissy.

Meg slid off Gwen, bum first. Gwen lifted her head.

Up the sidewalk toward them strode Shepps with a greasy paper bag in one hand and Sara’s hand in the other.

Gwen rose and ran toward the two while Meg tripped and toddled behind. Gwen fell to her knees at Sara’s feet. She cried and reached for Sara’s thin calves. Sara pushed at Gwen’s shoulders with all of her wiry might, pushed her to the ground.

You took Sock Daddy away, Sara yelled.

She stomped her feet. She grabbed at the end of the sock dangling from Gwen’s right hand, but Gwen held firm. Gwen pried Sara’s hands from the sock and held them in her own. Sara drummed at Gwen’s chest with her fists and collapsed into her lap. She cried until Shepps pulled a doughnut out of the paper bag and gave it to her. He retrieved another and fed it to Meg’s pudgy, pulsating fingers. He sat down beside Gwen and told her he’d found Sara by the van last night. That she was looking for the sock.

Where were you? Gwen said.

What?

When you found her. Were you out with someone?

Really, Gwen?

Forget it. Why didn’t you get me a doughnut?

Shepps sat quietly for a long time. As long as it took for Sara and Meg to lick all the icing off their doughnuts and eat the rest in bird-sized allotments. Then he put a hand on Gwen’s thigh and squeezed it in that paternal way of touching a once-familiar, now-taboo surface.

You need to drive away, Gwen said.

Will you be okay?

I don’t know.

Shepps gave her that look again, smug pity. Smug pity mixed with relief and a touch of sadness. He released her thigh. He looked at her but said nothing. Too earnest for I love you, too sentimental for goodbye.

Gwen stood and watched the girls roll in the grass and tongue icing from the paper bag. She walked toward Shepps’ van, the space that would soon replace it. She listened to the put-put-put, the van’s passive-aggressive roar when Shepps turned the key. As he crawled away from her, Gwen threw the sock at his back window, which it lazily grazed before flopping into a catch basin at the side of the road. When the weather turned, it would disappear into the storm drain, the ocean. A different world.