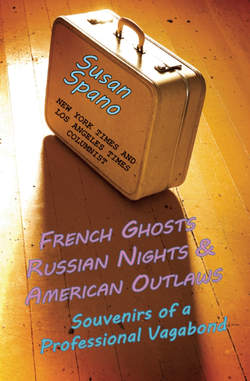

Читать книгу French Ghosts, Russian Nights, and American Outlaws: Souvenirs of a Professional Vagabond - Susan Spano - Страница 15

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление5

THESE VAGABOND SHOES

Somewhere around the 22,834-foot Aconcagua Peak, I decided that my highway map of Argentina hadn’t been a good buy; it was huge and unwieldy, with a tendency to antagonize bystanders when I unfolded it. Also, it showed the whole country—2,300 miles long from the Paraguayan border to Tierra del Fuego in the south—when I needed only a three-inch strip in the middle.

My 1,000-mile route began in Santiago, Chile, and took me over the Andes and across Argentina to Buenos Aires. I left Santiago on a Saturday morning in late February, with little more than a backpack and a bag, that map, and the certainty, gleaned from guidebooks, that it’s possible to go almost anywhere in Argentina by bus. Driving the whole way didn’t appeal to me. I could have flown, but I wanted to spot a gaucho on the pampas. And although a train does cross from Buenos Aires to Mendoza on the eastern flank of the Andes, there you’re stuck (though the disused tracks wind up the wild, lonely canyon of the Mendoza River and over the mountains at the 12,6000-foot Uspallata Pass).

However, Argentine bus companies ply routes that make a spider web of the map, with poetic names like El Porvenir (the future), 1 de Mayo (the first of May), and La Veloz del Norte (the speed of the north). So, of course, I romanticized the trip, poring over Bruce Chatwin’s In Patagonia and studying photographs in travel magazines of Argentine estancias now open as inns. I even got the buses themselves wrong, imagining chickens and bald tires; cheap, Argentine bus travel has more to do with loud, piped-in pop music, mini-skirted stewardesses, and subtitled movies made for American TV. If you pay slightly more, you can book a sleeper bus on overnight journeys, and bus stations in larger towns are remarkable minimalls.

Still, the reality of the trip didn’t make it any less an adventure. Were I to do it again, I would give myself more time so that I could detour at will to out-of-the way spots only touched on in guidebooks—birthplaces of famous Argentine statesmen, offbeat religious shrines, and the like. As it was, I saw the Andes, Mendoza, some of the country’s best-preserved colonial architecture in Cordoba, and a good deal of countryside.

I came to enjoy rolling into a town, getting a sightseeing map at the tourist information office (situated in most bus stations), and then striking off on foot in search of a hotel room. I was able to see a lot that way and felt free to do precisely as I pleased—although sometimes I made mistakes.

It might have been a mistake to book a more expensive shared taxi from Santiago to Mendoza instead of taking the less expensive bus ride, but a gregarious man in the Santiago bus station convinced me it would trim two hours off the seven-hour trip. I will never forget that ride in a battered chocolate brown Ford Falcon with three other utterly silent passengers and a driver who chain-smoked while I inhaled gas. He drove the Pan American Highway like a maniac, ascending the bone-dry, scrub-covered Andes, where little grows above 11,500 feet, flying around an amazing series of switchbacks leading to the border, and then finessing us through Customs and Immigration by exchanging a few chummy words with a uniformed guard at the barricade. Stunned by the swiftness of the ride and yearning to see the sights, I kept asking, “Donde esta el Aconcagua? Donde esta el Cristo Redentor?” Blithely, the driver gestured with his cigarette toward the highest mountain in the Western Hemisphere, but we never saw the statue of Christ erected in the mountains to celebrate the settlement of an Argentine-Chilean border dispute in 1902; it is off the road.

Clearly, if I wanted to see anything along this popular pass through the Andean cordillera, I’d have to go back. This proved easy enough, because Mendoza, where the taxi let me off, is western Argentina’s excursion central; from there, scores of tour companies take travelers into the mountains, for visits to the vineyards south of town, on whitewater rafting trips down the Mendoza River, and trekking along the 23-mile northwest approach to Aconcagua.

With limited time, I chose a daylong van tour that retraced the taxi’s route northwest along the Mendoza River, this time going slowly enough for me to appreciate the glitteringly metallic mountains. (Suddenly, I understood why Spanish conquistadores felt sure they concealed cities of gold.) We learned about General José de San Marin’s Andean guerilla battles with the Spanish in the early ninteenth century at a historic site in the oasis-like hamlet of Uspallata; took a tram ride up the deserted ski slopes at Los Penititentes, with snaggle-toothed peaks on every side; dipped our toes in the yellowish thermal waters at a natural bridge; walked a half-mile up Aconcagua, panting in the thin air; and visited Cristo Redentor. With outstretched arms, the statue gives a benediction to what is surely one of the bleakest places on earth, an abandoned border crossing—though “falling” might be a better word, since from the statue, it’s a 13,000-foot drop to Chile.

Meanwhile, inside the van, the portly driver, Alfredo, argued in Spanish about futbol and politics with a radio sports-caster from Buenos Aires; when I concentrated, I could almost understand. The newscaster occasionally deigned to talk to me, specifying that he had been taught “English English” in school. On the road back from Cristo Redentor, his girlfriend, a nurse with a shy teenage daughter, took out a vacuum flask of hot water and prepared mate, Argentina’s tea-like national beverage brewed from the leaves of the Ilex paraguayensis plant and drunk through a straw; graciously, she passed me her handy traveling gourd, and I found that I liked the bitter elixir.

I also liked Mendoza, the capital of Mendoza Province, where I spent the day before my mountain tour roaming delightful avenues lined with gnarled plane trees, wide irrigation channels, and tile sidewalks meticulously cleaned every morning with kerosene. In the town’s old section (partly spared from frequent, disastrous earthquakes, like the one that virtually leveled Mendoza in 1861), I took in the ruins of a Jesuit mission dating from 1638 and a small but well-designed archaeological museum, followed by a mouthwatering steak at a shady alfresco grill.

I could have seen the sights of Mendoza in one day. But I wasn’t quite ready to get on another bus, so I spent the next day visiting the highly mechanized Penaflow winery south of town. I also checked out the central market and marveled over the liver, brains, tripe, and a green squash the size of a baseball bat, then frittered away the afternoon in the Plaza España. Of all Mendoza’s many parks, this seemed to me the loveliest, with walkways and benches made of tiles bearing pictures of heraldic shields, sailing ships, and Spanish castles.

That night, I boarded the bus for Córdoba, traversing the arid countryside west of the Sierras de Córdoba through the wee hours. If I had wanted to spend 20 hours rather than 11 on a bus, I could have left in the morning and seen more, but I still had the 10-hour trip to Buenos Aires before me and didn’t want my limbs to atrophy. On board, a stewardess served us a dinner of boiled mystery meat, potatoes, and jug wine, then screened an American police flick while I sank into my deeply reclining seat. I would have slept were it not for my seatmate, a salesman who peddled tapes to discos across Chile and Argentina, snored loudly, and spoke English—too often and too well. When he saw that I was reading a novel by Isabel Allende, cousin of Chile’s deposed socialist president Salvador Allende, he told me to watch out, or people would think I was a communist.

Around dawn the next morning, we crossed the Sierras, blanketed in trees and thick fog, and then descended toward sprawling Córdoba and the pampas beyond. Bleary-eyed, I made a reservation at the tourist office in the bus station for a room in a modern hotel that had a private bath and included breakfast.

I was getting the sniffles by the time I reached the hotel, and in a cold drizzle, Córdoba seemed grim, as well as noisy and congested. Still, I rallied to tour one of the oldest cities in Argentina, founded in 1573 and for decades thereafter far more vigorous than Buenos Aires, although its architecture is by and large modern now. The buildings on Calle Obispo Trejos that house the Universidad Nacional de Córdoba and Colegio Nacional de Monserrat are Spanish colonial gems, as is the Córdoba Cathedral on the Plaza San Martin, with an impressive three-tiered dome and an exterior that looks like a melting lemon ice cream cone. Next door is the city’s handsomely restored Cabildo, where I found a fascinating exhibit on the great bullrings of Spain. Best of all, though, was the display of antique fanals—glass-encased baby-Jesus figurines surrounded by dried flowers, fruit, paste jewels, and other colorful geegaws—at the Museo Historico Provincial Marques de Sobremonte.

At noon the next day, I took a seat on a Chevalier bus bound for Buenos Aires. This one didn’t show movies or serve food, so I carried a large bottle of mineral water and a package of dainty, crustless ham and cheese sandwiches, kicked off my shoes, and watched the pampas roll by. The flat fields of sunflowers and corn, grain elevators, and fly-speck towns looked so much like those on the North American plains that I kept having to remind myself I wasn’t in Kansas anymore. Across the aisle from me, a sweet elderly couple sipped mate. Then, as we approached the federal capital, the loudspeaker announced our imminent arrival with Frank Sinatra’s rendition of “New York, New York”—which made me laugh out loud as I put my vagabond shoes back on.