Читать книгу In the Country of Women - Susan Straight - Страница 11

ОглавлениеTo my daughters:

They never tell us about the odysseys of women. They never say about a woman: “Her passage was worthy of Homer . . . her voyage a mythic quest for new lands.” Women don’t get the Heroine’s Journey.

Men are accorded the road and the sea and the asphalt. The monsters and battles and the murders. Men get The Iliad and The Odyssey. They get Joseph Campbell. They get The Thousand Faces of the Hero. They get “the epic novel,” “the great American story,” and Ken Burns documentaries.

But our women fought harder than men—they fought men! Men who claimed to love them, to protect them, to help them—men who trapped and tried to kill them. They fought for sons and daughters, they had the battalions of their sisters and mothers and aunts. Some bad-ass aunts. The women used their cunning and their bullets, the power of their ancestors and of the other women in the wagon or the truck with them. They survived passages that would have made a lot of men quit. Sometimes the men did quit. Sometimes the women quit the men—to stay alive.

The women might have wanted to return home. But they couldn’t. They were not Odysseus, with rowers and soldiers, returning after conquer and plunder. These women had to travel to new worlds—pioneers and explorers, mythic as goddesses of war and love and intellect—because the old world was trying to kill them, starve them, or bury them alive.

Our women were not in history class, or film, or the literature of “the canon.” Our women survived the men who survived the cannons of war, and those were hard men. We hung out with hard men. Weak men. Good men. We married them. We got the babies. The violence. The guns. More babies. The laundry. The pots. Dancing. Pigs. The barter—sex and beds and sheets. The chickens. The bread.

We kept the nation alive.

The women who came before you, my daughters, were legends. Their flights lasted decades, treks that covered America, after they arrived here from the continents of Africa and Europe and married into the indigenous peoples of this continent. They crossed countless rivers. They were, like Odysseus, imprisoned and seduced and threatened with death. They slept with lotus-eaters and escaped monsters like the Cyclops and Charybdis, and sometimes they battled other women who were Sirens or who tried to steal their children.

Because they always had their children on the boat, and even other women’s children for whom they had become responsible. Odysseus survived everything to return to his wife and son, but he didn’t have little kids on his boat. Though he kept losing his soldiers, he started out with a damn army, and instead your female ancestors had endless brigades of foolish and jealous men trying to stop them.

These women had murder and marrow on their minds. They shed blood for us.

Fine, who was your father’s great-grandmother, utterly alone after her enslaved mother died when she was six or seven. No sailors on her ship, no gods to capture winds in a leather pouch and deliver them to her for speed when she fled the violence of Reconstruction in Tennessee.

Daisy, your father’s grandmother, a lovely trickster who kept secret the identities of the men who fathered her four daughters—even, as they say, taking their names to her grave. A woman with a smile so incandescent she was threatened with death if she took her face away from her first husband. Her single captain was Aint Dear, a fierce goddess of retribution herself after they fled Mississippi.

Ruby, my paternal grandmother, her hopeful travels in a Model A Ford with a battalion of five sisters, from Illinois to Colorado and then marriage to someone she fled again and again—the sisters her aid, the husband her love and her enemy, until the Rocky Mountains claimed her.

Rosa, my mother’s stepmother, a woman from a Grimm’s fairy tale, a stern and tireless general who with no assistance kept my feckless grandfather and his children alive by leading them to Fontana, California.

The promised land. All the women ended up in Calafia, a mythical island ruled by a warrior queen, whose inhabitants were black women. It is said our state was named for her.

The Odyssey was an epic poem meant to be declaimed aloud to people assembled for hearing the tale of harrowing travels home, for loyalty and love. We heard our stories spoken cautiously, or whispered. Here are the women. The origin bodies for thousands of Americans, including you, my daughters.

My mother gave me my first book when I was three. I read the Greek and Roman myths when I was five, in D’Aulaire’s wonderful illustrated anthology, because a kindergarten teacher was kind to me and let me sit in the corner with books. I was mesmerized by the pantheon of gods and goddesses, memorized their powers, fascinated by The Odyssey, by the monster Scylla and the beautiful Sirens. I imagined myself running like Diana the Huntress when I was attacked by boys or men, actually prepared perfect scathing rebukes, like Athena, who sprang from her father’s head fully formed and intellectually whole. My father was gone, and my mother was working, but I sprang from the pages of books fully formed, though I was so small and thin and ugly I was often invisible, except for when I was hunted as a girl and young woman, as so many of us were then, and I had to use what I’d learned in books to escape.

Sometimes the women in our family didn’t escape.

The women crossed thousands of miles of hardship so that when I was fourteen and your father was fifteen, he could walk one mile from his house to the end of my street—no one had cars, no one had any money for a date, we met only in parks—where he bounced a basketball in the playground of my elementary school. I walked there to meet him. We sat on the wooden bench against the chain-link fence that separated the playground from the railroad tracks twenty feet away. His shirt: white waffle-weave long underwear with the sleeves cut off for a tank top. I remember the smell of freshly laundered cotton and Hai Karate even now. My shirt: a halter top I’d sewn from two red bandannas, from a pattern I found in Seventeen magazine. We talked for a long time in the darkness, played a few games of H-O-R-S-E (I wondered why it was always horse and never something more entertaining, like platypus or elephant or anaconda), and returned to the splintery bench. We kissed for the first time.

His arms were the color of palm bark—brown with a glossy red underneath—and his fingers so long and elegant that when he put my palm against his, my whole hand barely came to the middle knuckles. My arms should have been pale, but this was 1975—some girls rubbed Johnson’s baby oil onto their skin and lay at the beach or beside pools to get brown. I had the baby oil—but no beach or pool. I mowed lawns and lay in the bed of my dad’s truck while he drove us to the desert.

Your father pointed to the dark brown dot on the skin below my collarbone. “What’s that?” he said quietly.

Was I supposed to say mole? Mole sounded terrible. A blind animal nosing out of the earth. I was so nearsighted I could barely see the playground, because I’d left my glasses at home. “Beauty mark?” I said.

He laughed. “That’s if you paint it on your face.”

“Who says?”

“All my aunts.”

I remember too the smell of sulfur in the rocks along the railroad tracks, and the pepper trees nearby with their spicy pink berries.

Thousands of miles of migration—from slave ships arrived to America, from boats leaving Europe after World War II, from indigenous peoples, hardened ranchwomen, and fierce mothers. The women moved ever west, fled men, met new men, made silent narrow-eyed decisions in the darkness, got on buses and in cars and walked for miles to survive. West until there was no more west.

We were born here, to more dreamers of the golden dream, the ones you never hear about. We moved through the streets of southern California, still with no money, but we had more than those women did when they were girls. We shared one burrito four ways, we rode eight to a car in a Dodge Dart or crowded the bed of a Ford pickup, we partied in the orange groves or in a field by the towering cement Lily Cup, where our friends’ parents worked at the plant making paper cups that Americans used to hold at the water cooler.

More than a year later, your father finally picked me up in the Batmobile, a 1961 Cadillac with vintage paint oxidized brown as faded coffee grounds, with huge fins as if sharks would chaperone us down the street. The sound was like a freight train. Sitting in the passenger seat, I saw a dark stain along the inside of the door. It was cold, and I asked your father to roll up the window, but he didn’t want me to see the spiderweb cracks around the bullet hole in the glass. Some guy had been leaning against the car window when he was shot. The stains were reminders of his blood. General Sims II, your grandfather, had bought the car from under a pepper tree where it had sat since the murder, covered in California dust. Your father drove me a mile and a half, to General and Alberta’s house, and in the driveway Alberta held out her hand and said, Come and make you a plate, and my life changed.

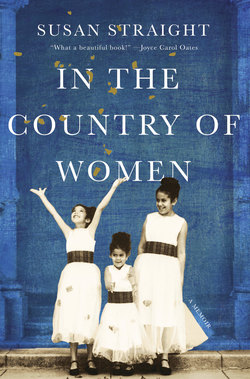

That is how you, our three daughters, became California girls. Via the Batmobile. You are the apex of the dream, the future of America, and nearly every day of my life I imagine the women watching you, hoping they—the ancestors—won’t be forgotten.

In the country of women, we have maps and threads of kin some people find hard to believe. The women could not have dreamed that in this promised land we would still have bullets and fear and murder. Fracture and derision and assault, sharp and revived.

I was born here, and I am still here, and I didn’t leave, which doesn’t feel very heroic. You three have laughed at me for looking out the kitchen window of our house toward the hospital where I was born, where your father was born, where you were born. My daily life is a five-mile radius of memory and work and family. You three daughters know this in your genes: You love only orange-blossom honey, because you grew up with that scent and those flowers, that fruit and those bees. You long for Santa Ana winds and sunflowers, tumbleweeds and the laughter of people eating at long unfolded tables in a driveway. We bury descendants of the women, and we serve funeral repasts in church halls built by some of California’s black pioneers. The women in our family are everything: African-American, Mexican-American, Cherokee and Creek, Swiss, Irish and English, French and Filipino, Samoan and Haitian. Some of their heritage remains a mystery.

I was not beautiful, and I never went anywhere. But I’m the writer. When I was seventeen, and left for college in Los Angeles, one of my first class assignments was a Xeroxed copy of Joan Didion’s famed essay “Some Dreamers of the Golden Dream.” I read it three times, actually breathless. Her sentences were lapidary and precise. She dissected the place where we live with lovely caustic prose: “This is the country where it is easy to Dial-A-Devotion, but hard to buy a book. This is the country in which a belief in the literal interpretation of Genesis has slipped imperceptibly into a belief in the literal interpretation of Double Indemnity, the country of the teased hair and the Capris and the girls for whom all life’s promise comes down to a waltz-length white wedding dress and the birth of a Kimberly or a Sherry or a Debbi and a Tijuana divorce and return to hairdressers’ school. ‘We were just crazy kids,’ they say without regret, and look to the future. The future always looks good in the golden land, because no one remembers the past.”

I was stunned.

She was writing about us, except for the Dial-A-Devotion. (I never knew anyone who did that.) My mother and all three of my aunts had been “divorcees.” One aunt had been married three times. One was recently divided from a Fontana Hell’s Angel biker. My stepmother was divorced when she met my father; she was now his third wife. My friends—black and white and Japanese-American and Mexican-American—were named Kimberly and Sherry and Debbie. We lived amid the citrus groves described in the essay, with low walls built of riverbed stone.

I went home that weekend, passing through the places Didion’s essay made famous: Ontario, Fontana, and Rialto. Finally I got to Riverside, and in my mother’s kitchen, standing at the Formica counter I had spent half my life scrubbing, I tried to explain the piece to my mother. She was distracted, cooking, not interested until I read part of a paragraph out loud, wherein the cheating wife pushes a burning Volkswagen that contains her unconscious husband into a lemon grove. My mother looked up at me then, and said, “That was Lucille Miller. Your aunt Beverly lived across the street from that woman when it happened. She always said Lucille was going to kill someone.”

I was further stunned.

I went outside to look at the palm tree in our front yard, whose stair steps of gray dessicated bark I had climbed when I was five, everyone shouting at me to get down. I knew a version of us, of the girls and women here, that was not in the essay. Debbie Martinez, Deborah Adams, Deb Clyde. Girls descended from Mexican and black families arrived in the 1920s, and white families arrived from Arkansas after the Korean War. Our mothers and grandmothers remember their pasts.

I wanted to write about us.

Your father and I took our first journey three days after we were married in the oldest black church in Riverside, Allen Chapel African Methodist Episcopal, founded in 1875. (The afternoon of our wedding, we were driven around the city lake in another Cadillac, belonging to our friend Newcat, a car with a broken horn, so that your uncle General III stood in the open sunroof, his arms spread wide, shouting to people, Honk, honk, goddamnit, these two fools just got married!) We drove across the country from California to Massachusetts, in a Honda Civic—a truly tiny car back then, in 1983, and your father was six feet four inches and 195 pounds, so it was no joke sleeping in the front seats at rest stops.

In Amherst, we found a mattress and some furniture on the street and lived in a studio apartment while I learned to be a writer and your father worked nights in a correctional facility. But we met James Baldwin, my teacher and mentor. His driver, Rico, and his secretary, Skip, were tall black men who wanted to play basketball with your father. So everyone came to dinner in our bleak front room with two card tables we’d borrowed, the gray linoleum scrubbed, and the tiny red television my brother had won by selling newspaper subscriptions when he was twelve, which he’d given me for Christmas seven years earlier.

James Baldwin said the apartment reminded him of old days in Harlem. He walked the floor slowly holding a glass of Johnnie Walker Black Label, leaning toward my small blue typewriter on the windowsill, reading the handwritten note I had taped to the glass:

With the rhythm it takes to dance through

what we have to live through

you can dance underwater and not get wet.

He turned to me, his voice precise and resonant as ever but with the wonder he always allowed himself (I already knew that was who I wanted to be—someone endlessly willing to look at something new and feel continuous wonder), and said, “That’s the most extraordinarily profound thing I’ve read in a long time. Who wrote this?”

George Clinton, we told him. On our ancient black boombox kept on the windowsill, too, we played a cassette tape of “Aqua Boogie” for James Baldwin, the song whose refrain kept me going in the cold snowy nights when I missed oranges and friends and pepper trees. We told him about home. He said to me, “This is remarkable. This is what you must write about. Your lives.”

I was twenty-two then. But I wasn’t ready.

Now mourning and love shape this memoir. Our elders are dying, and our young people, too. Your great-aunts, your aunts, and your cousins. Our country feels as if it has gathered itself at a cliff and is studying the long scree of loose rock, deciding whether to slide down and descend completely again into open hatred. This is a different memoir than the one I thought I would write when you three girls were small, when you were Our Little Women, and this was our Orchard House, though our orchards were orange trees.

You three daughters have left us, your father and me, and many of the women we loved are gone as well, so we are here with our kin in the city where we were born, still sitting under the trees in the searing heat near the big grill where entire slabs of ribs smoke for hours, and then we women chop them into single bones with hatchet and ax so the kids can hold one curve of glistening meat and hear again about how their great-grandfather General II didn’t want to eat squirrel ever again after Oklahoma.

All of American history is in your bones. In your skin and hair and brains and in your blood. Your kin family numbers five hundred or more. When your cousin Corion died last year, at twenty, our grief was depthless. He was a skateboarder, walking home, having just passed the driveway where our family’s heart has gathered for fifty years, and so I see him walking still. At his funeral, I read this poem, by Linda Hogan, Chickasaw poet of Oklahoma and Colorado, two places where our stories originate. It seems the right way to begin:

Dwayne Sims, Skip (“I’m the secretary”), James Baldwin, Rico (“I’m the driver”), at Baldwin’s rented house in Amherst, Massachusetts, 1984

Tonight, I walk. I am watching the sky. I think of the people who came before me and how they knew the placement of the stars in the sky. Listening to what speaks in the blood. I am listening to a deeper way. Suddenly all my ancestors are behind me. Be still, they say. Watch and listen. You are the result of the love of thousands.

And thousands of miles, by foot and boat and train.

I see the women moving about in the darkness, not because I was in that darkness with them, but because the air was dim or dust around us when the stories were told. The people who spoke to me looked off into the distance, or out a car window, their voices low and rough talking about the night or day when life was altered in a moment. Many stories had a beautiful woman, a murder or tragic death; many had a terrible man.

One afternoon, sitting by the living room fire, our knees inches apart, her crimson lipstick gleaming, winged eyebrows drawn together and then rising in surprise, my mother-in-law, Alberta, waited for me to hand her Gaila—my first daughter, finally fallen asleep with milk on her lips. Then Alberta spoke softly about Sunflower County, Mississippi.

Other days, under the eucalyptus trees shedding their creamy beige bark around us, their leaves like silver sickles, our cousins and uncles would hold paper plates of barbecued meat on their laps, speaking of Denton, Texas, and Tulsa, Oklahoma.

In the dry-grass-scented night of the Colorado prairie, in a tiny house moved from a ghost town fifty years earlier to Nunn, a town going ghost now, five elderly cousins of my grandmother told me for the first time about a country dance.

On a November evening, my mother crying, the wooden clock from Switzerland clacking implacably above us, the clock from the tiny village in the Alps where she was raised, like Heidi, where when she was nine, her mother died, just like Heidi’s, and my mother told me she went down in the night to see her mother’s body in the living room, and now her life was ruined here in Glen Avon, California.

When I went outside the next day, the chain-link fences were white with feathers heaped onto the wires like insanely monstrous snowflakes, and the Santa Ana winds were blowing, and I tried to figure out how someone would lay a dead woman on a table. I was three years old, and felt as if not just me but our entire street could be lifted up and moved to a different world by that wind, which always blew west, into my face, so that I had to close my eyes.