Читать книгу In the Country of Women - Susan Straight - Страница 14

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление2

The First Bullet

Fine, Near Murfreesboro, Tennessee, 1876

She was

called Fine when she was orphaned. Then her name changed for each man in her life, for seventy years. She became Fin Hofford, Viney Rollins, Fannie Rollins, Tinnie Kemp, Fanny Kemp, and finally, in letters carved onto her headstone in a historic black cemetery outside Tulsa, Oklahoma:

BELOVED GRANDMOTHER

FINEY KEMP

1874–1952

nothing but

a new possession to the white people who took her from the former slave cabin in the countryside northwest of Nashville, where she was born maybe in 1869, only four years after the Civil War ended, according to an 1870 U.S. Census document, or maybe in 1874, according to information written on an application for social security just before her death.

It doesn’t matter. By the time she was five or six, Fine was a child bereft. Adrift.

Like countless children during Reconstruction, a violent maelstrom of greed and revenge and ruined land, Fine moved through the world alone. Small wanderers were everywhere along the roadsides, among the trees, in the edges of the yards.

Bereft of all love and care. Bereaved is what we feel when someone dies. Bereft is when we are left without anything.

Henry Ely, her father, had been “run off by the law,” Fine told her grandchildren, said to have made his way to Texas. Shortly afterward, her mother, Catherine, died in the place where she and her own sister had been enslaved for their entire lives. Fine was the youngest of five children. Imagine the children in the cabin doorway, watching wagons enter the yard to take them away.

Fine told the story of her life to her daughters and her grandchildren in Oklahoma and California; as her grandchildren became our elders, they recounted the details at family gatherings, and now the last surviving grandson of Fine, our beloved uncle John Prexy Sims, is eighty-two years old and tells her story to our own children.

“They took her by herself,” he said. “Her mother was dead and her father was gone. There was no one to contest the white people who came and picked the little ones out like puppies. The family that took her called her Fine simply because she looked strong and healthy.” She never saw her family again.

John said, “Her father was a Cherokee man, and he was in love with two sisters who were slaves. They were so beautiful he couldn’t pick one. So he loved them both.”

Family legend: Catherine and her sister lived together in one slave dwelling. Henry Ely was a free man, not allowed onto the plantation, so he dug a tunnel from the forest at the boundary of the land and under the fence. He planned the tunnel to open up into the dirt floor of the cabin of the sisters. (Like a fairy tale of a prince and two princesses—the fairy tales we were all told of captive women and a man whose love might rescue them. But this was 1850s Tennessee.)

Free men of color were often killed or forced out of the area by slaveowners or vigilantes. New laws made the very presence of men like Henry illegal. If Henry was Cherokee, his life was endangered by President Andrew Jackson’s Indian Removal Act. Jackson wanted the west, and Tennessee was then part of the west. Manifest Destiny—painted landscapes with white angels wearing white garments hovered over the wagon trains of white settlers as they crossed the Appalachian Mountains into Tennessee. The indigenous peoples known as the Five Civilized Tribes, Cherokee, Chickasaw, Creek, Choctaw, and Seminole, were forcibly removed by American militia from Tennessee, Georgia, Mississippi, Alabama, and Florida, sent on the winter death march known as the Trail of Tears to Oklahoma Territory.

Whoever Henry Ely was, he called Catherine his wife, and they had six children. (The names of her sister and the children of that sister, and whether they were fathered by Henry are unknown.)

By the time her family disintegrated, when Fine was about five, Reconstruction meant violence, starvation, and murder for freedmen and freedwomen. The Freedmen’s Bureau made reports such as these, in 1866, in Murfreesboro, near the place where Henry and Catherine lived, where a “colored” man gave testimony:

July 28, 1865: “Ben (col’d) says on the 29th of June, ‘Beverly Randolph beat my wife with his fists then caught her by the chin threw back her head pulled out his knife swore he would cut her throat’—(the woman was large with child at the time.)” Randolph was fined $50.

The Freedmen’s Bureau reported further: “The freedmen are daily driven from their homes without a cent after having been induced to work the year with a promise of a share of the crop. Husbands are not permitted to claim their wives or parents their children, women have been struck to the ground and choked.”

“A freedman living twelve miles south came in last night, covered with blood, with severe cuts on his head—his former master had beaten him with a heavy stick while his son-in-law stood by with a pistol, because the freedman had said that he intended to go and hunt up his children, whom he had not seen in four years.”

This is the world Fine was born into.

She had lived in a small cabin with her people. Then there was a wagon—she either rode or walked behind. Did she cry and scream, when she saw her siblings taken away? Or was she taken first? She went alone. She never saw again the brothers and sisters with

Skin

that looked like hers and now her life was filled with cruelty, especially at the hands of an elderly matriarch to whom emancipation meant nothing.

John Sims’s voice still resonated with hurt when he talked about Fine: “She told me many stories about her life with the family that took her. Her food was scraps from the plates of the family, or whatever wild nuts, fruits, and berries she could find. Her clothes—castoffs from the family. She found that she could earn a little money by selling the wild blackberries that she picked (five cents a gallon). This little money she would save in hopes of buying a pair of shoes, but in spite of her efforts to find a safe hiding place, the family would find the money and take it away. Beatings came at the least little thing, from all members of the family, especially from the old woman, who was nearly bald and suffering from mouth cancer.”

Fine wanted shoes. She wore rags, chopped wood, brought water from the well, and still the old woman beat her as if the beatings were the old woman’s work, the schedule and imprint of her former life. Maybe she had beaten children all her life, or maybe she chose to beat only this one child, who would not be subdued.

Fine was in tatters and cold. She was hungry. Inside, she was a furious whirl of anger. She was skin

and Bone

in the yard: well and woodpile, field and house. The woodpile. The insatiable need for wood to cook and wash clothes and always more wood. Her bare feet. Her anger.

One day there was a glint of metal on the ground.

A bullet. All those bullets, balls of lead aimed at the heads of soldiers on both sides, and then freedmen and women, the countryside near Murfreesboro littered with bullets and cannonballs and bones and even unburied bodies. Decades of war and retribution. Hunting and killing of animals and humans.

Fine put the bullet into the pocket of her apron. It was her talisman. She was about eleven years old. In her mind, having not a single human to help her, she was capable of murder. She didn’t know anything about gunpowder or firing pins. She only knew people died from bullets.

John Sims said, “Grandma (we pronounced it Gramaw and still do) was out picking berries (she never went to school!) and came upon a cartridge lying by the side of the road. She thought it to be a weapon all by itself. With great care, she hid it away for just the right moment. One day while chopping wood for the family stoves, the old woman came out to watch her . . . Gramaw told her, ‘These wood chips flying and you liable to get hit!’ The old woman told her to shut up and get to work. Soon the opportune moment came. When the old woman was looking away, Gramaw took the bullet out of her apron pocket. With all her might, she threw it at the old woman’s head. It landed flush on the temple. A bloodcurdling scream from the old woman that could be heard all around the farm brought the rest of the family on the run. Gramaw told them she said to watch out for the wood chips, but she still got a beating, which was the least of her pain. The one weapon she thought would give her a taste of revenge was a bitter disappointment. How can it be? she wondered. I know it hit her. Why didn’t she die?”

She had cheekbones like ledges of slate under her eyes, and black hair thick and long. She was thirteen. She wanted shoes. She headed to the blackberry thickets along the edges of the woods, picking buckets of berries to sell to people passing by in wagons. It was 1887. She met a young man by the roadside. Robert. He might have been seventeen or eighteen. Fine fell in love. (The word is always fell, not leaped or landed or rested or dived. Fell.) She ran away with him, and he took her to an old shack in the woods built for migrant workers. Soon she was pregnant.

No one ever says whether the white family tried to find her, or how far she had gone to be with Robert. When she grew bigger with child, Robert left, but someone in the area helped Fine give birth to her first daughter, Jennie. The father was listed as Robert Hofford. Fine was listed as Fin Hofford.

Shortly after, alone with the baby, Fine was up and about, picking cotton, picking and selling wild berries. Robert returned with the season, and left again, twice more. Fine gave birth to a son, Mack, and the following year, to another son, Floyd.

Her husband never returned. She was maybe sixteen or seventeen.

She lived in a series of migrant camps in the woods with three children. There was no way to survive, out in the wild between Murfreesboro and Nashville, where the landscape is full of mountains, hollows, creeks, forks, branches, and a vast area called the Barrens. The countryside had not recovered from the war, and the roads were full of people who had no work, no money, and no hope.

She believed there was only one human who would help her. For three years, she picked crops and wild berries, sold whatever she could, wore rags and fed the children, until she’d saved enough for train tickets to Texas. She had heard her father, Henry Ely, had gone to Denton.

Fine and the three children made it to Denton, which by 1900 was a city of five thousand people. She wandered the town, asking people about Henry Ely. No one knew anything about this man. The possibilities of what may have happened to a free man of color, whether he was Cherokee or part black, are endless. The Freedmen’s Bureau accounts of murder and kidnapping, of bodies dumped in rivers and woods, are only those of people who actually reported the crimes to government officials. The skeletons of freedmen and women were everywhere.

She was overcome by everything, at the end of the first day. She and the children had not a single penny left, no food, and nowhere to sleep. She sat on a log near a piece of land just at the edge of town, crying.

A man saw them from his farmhouse porch. She was sitting on the road below his land. His name was Zack Rawlings, or Zach Rollins, or several variations of those. He was fifty years old. She was maybe twenty-two. She was a beautiful young woman in desperate circumstances. He went outside to ask her whether she and the children needed a place to stay.

She gathered up her children and followed Zack Rawlings inside. She had no idea of the violence that would ensue here—a continuation and catalyst that would change her life again.

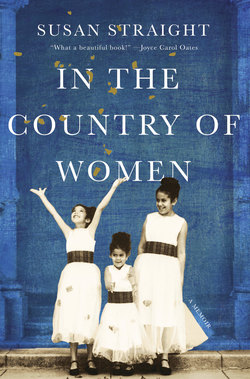

There is a single photograph of Fine, from the 1940s. Her cheekbones are high and wide, her hair curled carefully, her eyes large and brown, her lips held closed over her teeth. As a teenager, hearing these stories at my future husband’s house, in the driveway where her grandchildren were adults of immense physical presence, holding the ribs of pigs, talking about how she saved their lives, I imagined her as large and powerful. But she was slight and cautious. Watchful and intent. There was inside her a core of fury and independence and self-preservation, the genetic heritage of survival.

McMinnville to Nashville, Tennessee, to Denton, Texas: 714 miles, not counting the miles walked from the woodpile and the well to the house of the woman who beat her, or the miles walked in the forest picking blackberries and selling them in pails along the road.