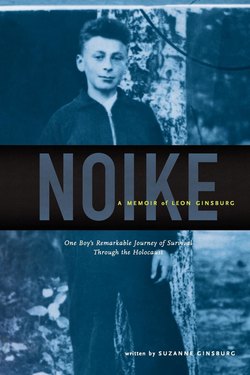

Читать книгу Noike: A Memoir of Leon Ginsburg - Suzanne Ginsburg - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

LITTLE BOY MEETS GIRL

ОглавлениеNew York ~ San Francisco ~ Florida

“Your dad looks great,” my father’s friend said, stabbing his fork into a hunk of noodle pudding. My older sister had purchased all of my dad’s favorite foods—noodle pudding, knishes, pierogis—for his birthday party at her house on Long Island. With my brother living in London and me in San Francisco, she had become the de facto family hostess in recent years.

“I know—I can’t believe he’s 70!” I replied. We both paused to take in the figure my father cut on the other side of the room, where he was telling a story to a few old friends from City College with his usual, animated flourish. My mother, sister, brother, nieces, nephews, and dozens of other guests were scattered throughout the house and backyard.

“He’s like Dick Clark,” my father’s friend continued, swallowing his last bite of noodle pudding. “One day he’ll suddenly get old—”

Forcing a smile, I picked up a mini-knish and stuffed it into my mouth. And die, I thought, completing his sentence in my head. My father’s friend didn’t mean any harm but his words were unsettling. He’s going to get old and die, right?

I’m not a morbid person. It had been almost ten years since I had contemplated my dad’s mortality during a drive to Newark airport. I had been in New York for a few weeks and was heading back to Japan, where I lived and worked for three years in the early-1990s. We were somewhere on the New Jersey Turnpike when a horrible scene started playing in my head: What if my dad had less than 24 hours to live? Even if I jumped on the first plane out of Japan, I might not make it home in time. I imagined rushing into the hospital room and the nurse saying, “Sorry, honey, you just missed him.” By the time we arrived at the airport I had become fixated on this scenario. Unable to share my morbid thoughts, I burst into tears and blurted: “I’m going to miss you!” My father was stunned; I never cried when saying goodbye. “I’ll see you soon,” he smiled, wiping my tears with a tissue.

Standing there at my dad’s 70th birthday, I had that same sick feeling, like I might lose him at any moment. San Francisco was closer than Japan, but it was still more than five hours by plane. Part of me knew that I was being dramatic, maybe even perversely grim, but I didn’t want to be one of those people that you see in the movies—slumped over a dead loved one, wishing they had said or done something meaningful for the deceased when they had the chance.

Later that evening, after most of the guests had gone home, my father started thumbing through a photo album that was assembled over the course of the party. In lieu of gifts—which my father never wanted–each guest was asked to bring a photo, with the only specification being that the image should resonate with my father in some way.

“Ho, ho, ho!” my father said as he looked at the first page. “Who are these gorgeous children?” He turned the album around and showed off a collage of his six grandchildren.

“That’s us, Zeidi!” Isabel said, climbing onto his lap. She was three years old, the youngest grandchild.

“And who’s this pretty little girl?” he asked, looking over at me.

He held up a page that bore a photo of us from New York, circa 1976. In it I’m wearing a short, checkered green dress and smiling for the camera; my father is standing over me in a floral button-down shirt and blue jeans. I was very much Daddy’s little girl back then, always running down the hallway when I saw his car pull into the driveway, eager to wrap my arms around his neck. I can still remember his soft brown hair tickling my eyes and nose as he hugged me, the feeling of relief when he finally walked through the door at night.

I CAN’T SAY HOW THAT PHOTO RESONATED with my father, but for me it called up powerful memories of our storytelling ritual during that period. Every night my father would sit beside me and tell me about a little boy who roamed the farms and forests of a faraway place, befriending foxes, dogs, and sheep. The stories were never scary, but they suggested mystery, and were tinged with the darkness of a certain kind of children’s fable. In one story, the little boy was sleeping in a haystack when a farmer poked him with a pitchfork. He wasn’t harmed but I wondered: Where were the boy’s father and mother? Why was he alone? At some point I realized that the young boy was in fact my father, but between us passed a kind of tacit agreement to keep his identity secret, to let him remain in the faraway forest. Like the homeless little boy, I knew my father had also lost his family; unlike the rest of my friends, I never had a full set of aunts, uncles, and grandparents.

The stories stopped when I became too old to be tucked into bed, or maybe it was when I started watching television with my mother. Unlike most families, our primary television—the only one without static—was in the master bedroom. My dad would sit in the kitchen to watch the evening news on the “small” TV, occasionally poking his head into the bedroom. “Who wants dessert?” he would ask my mother and I as we lay on the bed, transfixed by the latest Dynasty cliffhanger. “Not now, not now,” we would say, afraid of missing some critical part of the story. “What could be so important?” he’d ask, then leave the room with an incredulous shake of his head. A short time later he would return with some elaborate combination of ice cream, cookies, and cake for me, and tea for my mother, then tiptoe out once his work was done.

More than a decade later, I tried to recapture his stories within the confines of a college writing assignment. By then I knew that my father’s family had been killed in Poland, during the Holocaust, but I didn’t know exactly when or how. He had agreed to help me with some research for the assignment, and I remember sitting on the living room couch for several hours as he lectured me on the commerce, utilities, and transportation systems in his small Polish town. Not once did he mention my grandparents, aunts, uncles, or cousins; not once did he mention the war. I now see how naïve I had been: How could I have expected him to tell me—his innocent eighteen-year-old daughter—about the horrors he and his family had experienced?

WHEN I RETURNED TO SAN FRANCISCO after my dad’s 70th birthday, I kept thinking about his stories and the prediction made by his friend: He’s going to suddenly get old. Those words were a painful reminder that my father would not always be here to share his memories, to provide a window into the lost world of my aunts, uncles, grandparents, and great-grandparents. Flashing forward to the future, I imagined myself alone in his office, rifling through his reams of notes and old photographs with so many questions, wishing I had asked them long ago. The answers would remain trapped in his mind, his descendants left with only a vague understanding of what he had experienced.

I realized that I needed to find out what happened, right then, before it was too late. Not knowing where or how to begin, I enrolled in several writing classes and immersed myself in biographies, memoirs, and Holocaust history books. As I gained confidence, I started thinking about the logistics: Could I write his stories on nights and weekends? Should I request a sabbatical from my job? And then it came to me: I had to quit my job and focus on his stories. Without a full commitment, it would end up just like my college writing assignment—a few interesting historical facts but not the real story. I had been saving money for a down-payment on an apartment; it was more than enough to support me for one year. The apartment in San Francisco could wait.

When I finally shared my plans with my father, I was expecting a long discussion full of awkward silences, but he simply said: “I always knew you would do it.” It was as if the date and time were marked on his calendar; it was as if he had been sitting there, waiting for my phone call. His response made me feel like I was doing the right thing, that maybe I was meant to do this in some weird, spiritual way. I pictured the homeless little boy racing through the forest, joyful that his stories would finally be told.

ABOUT TWO MONTHS LATER, I flew from San Francisco to Florida, where my parents had recently retired. I planned to spend the entire four days interviewing my father, starting from the beginning. I had no idea how far we’d get, but felt we now had enough time not to worry: I had already quit my job; this was my number one priority.

“So, what do you want to do while you’re here?” my father asked as we drove from West Palm Beach airport to their home in nearby Boynton Beach. “Your mother said you might like Morikami Gardens or the bird sanctuary—they’re only about 30 minutes away. And of course there’s the pool and beach!”

“They all sound fun but I want to work on your stories,” I said, confused by the sightseeing suggestions. “Unless you changed your mind?”

“No, no, that’s good,” he said, lowering the radio. “I have all my papers organized for you!” He proceeded to list all of the maps, photos, and news clippings he had arranged in manila folders for my visit.

“Great, I can’t wait to see what you have,” I said, relieved that he, too, was serious about the interviews. I pictured him proudly telling all of his friends: My daughter is writing a book about me! Quit her job and everything. Can you believe it? It was probably the only time a Jewish parent could justifiably brag about their child not having a job.

At the entrance to their community my father clicked the remote control that lifts the gate, allowing us inside. We passed a large fountain, wound our way along the main road, then turned down my parents’ street. From the outside, their house looks like most of the others on the block: one level, light stucco exterior, red tile roof. The houses are spaced fairly close together, but many of the neighbors don’t know each other. A large number of the residents still work full time while others are “snow birds”—winter residents who head back up north when spring arrives.

“Betty, your daughter is here!” my father called as we entered the house.

“Did you miss your old mother?” my mother grinned as she approached the front door with her arms wide. Before I could reply she had begun an impromptu house tour, showing me what she had bought since my visit the previous winter. She avoided my father’s office, the one room in the house she’d agreed not to decorate. What furnishings it contained were buried under assorted piles of paper: dozens of books and articles, stacks of unfinished personal stories, newspaper clippings, and countless black and white photos of people and places known only to my father.

THE NEXT MORNING MY FATHER STROLLED into the kitchen wearing one of his newly acquired Florida outfits: a yellow-and-white striped golf shirt, khaki shorts, and Rockports. “Good morning!” he said. “Your mother already left for the fashion show but she’ll be back in time for dinner.” Hadassah, a group for Jewish women, organizes group outings like the fashion show each month; last time the ladies saw the King Tut exhibit in Miami.

“You slept well?”

“Not bad,” I replied, as I finished setting up the video camera. I planned to take hand-written notes but I wanted to make sure I didn’t miss anything. The video would serve as backup.

“Look at these birds,” my father said, pointing out the window. “I enjoy watching them, especially in the morning when they come to eat. It’s amazing how long they can stay underneath the water.”

Watching my father gaze at the birds, I realized that I had to take the lead and start asking questions. If it was up to him, we would spend the whole day reviewing Polish, Russian, and German history and the various pacts that led up to the war. Brushing up on my World War II history was critical but I was eager to immerse myself in the little boy’s world, in my father’s lost world. I wanted to walk in his footsteps, see what he saw in Maciejow, Poland in 1939. At the same time, I knew it was important to ease my father into the interviews. If he felt rushed or pressured, I was afraid he might shut down. Being a novice interviewer, I started with the obvious questions.

“Dad, you were born in Machiev in 1932, right?”

“Yes, but you’re spelling it wrong, it’s M-a-c-i-e-j-o-w,” he tapped at my notebook.

“And you were called Noah back then?”

“Noah was my Hebrew name; Noike was my Polish name,” he explained.

“So, when did things start to change in Maciejow?” I corrected the spelling of his hometown in my notebook.

“1939—that’s when we got occupied by the Soviet Union. September 17th, 1939. You know how I remember that date?” He did not wait for a response: “Because they renamed the main street ‘Sedimnazietavo Verezina. September 17th!”