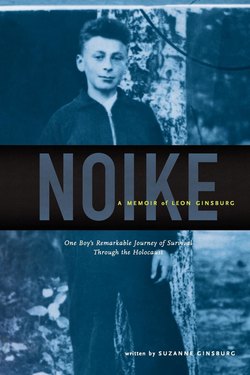

Читать книгу Noike: A Memoir of Leon Ginsburg - Suzanne Ginsburg - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление3

THE BLACK STORM

Maciejow, Poland. June 1941

Noike pulled his pillow over his head but the bombs were relentless—more frightful than thunder and lightning, more frightful than anything that had ever woken him in the night. He went into his mother’s bedroom and quietly stood near her bed. Sensing someone’s presence, she opened her eyes and softly smiled at her youngest child. “Come baby, come sleep with Momma,” Pesel said, placing a quilt around his ears and holding him until he fell asleep.

The German attack, code named Operation Barbarossa, took the Soviet Union by surprise. Hitler began planning the attack when the Soviet Union expanded westward in the summer of 1940 and occupied Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, and Romania. The Soviet Union had the largest intelligence network in the world, and yet Stalin refused to believe the countless warnings until hours before the Germans’ first strike. Within a few days the front reached Maciejow.

Noike ran to main street when the German Army entered the town. They made a big show, parking their trucks less than a quarter mile outside of Maciejow, then parading down the street in their fine military gear—freshly pressed uniforms with elaborate belt buckles, black leather riding boots polished to a shine. Onlookers gawked at the men, unsure whether to admire or fear the impressive show of military force.

Ukrainian women from the neighboring villages arrived in traditional dress and offered flower garlands to the soldiers. The soldiers placed the garlands around their necks, smiling as they waved and thanked their supporters. Most Ukrainians simply wanted the Germans to improve their economic situation; others hoped their new occupiers would finally pave the way for an independent Ukrainian state, free of ethnic Russians, Poles, and Jews. Members of established Ukrainian nationalist groups were rumored to have made contact with the Germans weeks before Operation Barbarossa, taking steps to secure coveted government positions previously held by the Russians and their followers.

One of Maciejow’s senior rabbis was also at the procession. He was an elderly man with a long, gray beard wearing a black hat and a kapote, a traditional black coat that brushed the ground. He had set up a small wooden table with bread and salt, the customary way to welcome visitors. The rabbi was extending his long, bony hand, offering a piece of bread and salt, when one soldier stepped out of the line, turned over the table, and shouted, “Get out of here!” Terrified, the rabbi hurried away, leaving his table and gifts behind.

How could someone do this to a rabbi?

Although the Soviets had transformed almost every aspect of life in Maciejow, they left the religious institutions and leaders alone. On Friday afternoons, the senior rabbi would put on his kapote and streimel, a round fur hat, and walk through the center of town, signaling the start of Shabbat, the Jewish Sabbath. One could hear the sound of store shutters closing as the rabbi passed through each block of town. The rabbis taught young and old, guiding the community for hundreds of years. Children would have to stand in the corner if they were disrespectful to them, yet this man had yelled at one of the most revered rabbis in the area.

When Noike shared the news with his mother later that afternoon, she tried to assure him that little had changed, but each day the world around him told a different story. One of the German authorities’ first tasks was to post signs outlining the racial laws imposed in western Poland: Jews weren’t allowed to walk on the sidewalk; Jews weren’t allowed outside their homes between six in the evening and six in the morning; Jews were required to wear a white armband that was ten centimeters wide and embellished with a blue star of David.

Noike did not fully understand the significance of these laws until he saw a German soldier drag Pinie Broinstein, an elderly Jewish neighbor, off of the sidewalk. The soldier reprimanded him for walking on the sidewalk, pulled out his bayonet, and savagely hacked off his beard, cutting his skin with each stroke. Mr. Broinstein tried not to weep as blood oozed from his wounds and dripped onto his white shirt collar.

Noike wanted to protest the soldier’s actions but he, too, was scared of the foreign giants with their guns and bayonets. He wondered if they would beat him if he walked on the sidewalk, or draw their guns if he was caught playing outside after curfew. Frightened, he again hurried home to tell his mother what he had witnessed.

“Noikele, look what Momma made for you today,” she said, handing him a warm pletzel covered with poppy seeds, onions, and salt. She had been able to alleviate most of his fears with gentle words, but sometimes there was no way to explain why something had happened, no way to promise that it would not happen again. “Maybe you can bring one over to Mr. Broinstein to make him feel better.”

Pesel urged Noike to stay close to home but he often wandered off, eager to investigate the latest commotion around town. He was walking over to the Beis Medrush synagogue, near the old market, when he saw a large fire burning in the center of the courtyard. One German soldier was ordering a bearded old man wearing morning prayer clothes—the talles shawl and t’fillin—to throw a Torah and other religious books into a fire, while two others were working a military camera: one ran the crank and the other filmed.

The old man held the books tightly, refusing to throw them into the fire.

The soldier started beating the old man with the butt of his rifle. The old man shook his head and quietly prayed as the rifle butt slammed into his back, his yarmulka slowly slipping from his head. The holy books eventually fell from his hands and were swallowed by the pyre. “Where is your God now?” one of the soldiers roared. “Where is your God now?” The film was made as propaganda to send back to Germany, to show that the work of the Third Reich was being carried out as planned.

The holy books were the same ones Noike had used in school. He started studying the Talmud and other scriptures even before he could walk. A man in the town, the belfer, would fetch children like Noike, carrying them on his shoulders to and from cheder, a home school for Judaic studies. They taught Noike to treat the holy books with respect. As he stood there watching the books burn, he was convinced that lightning would strike the soldiers down–that a God was watching—but nothing happened.

As a child who would strictly follow the rabbis and their teachings—sometimes too closely—Noike was bewildered by these incidents. A few years earlier his mother had served Shabbat soup without mandlen, Jewish soup nuts. “Where are the mandlen?” Noike demanded. “We don’t have them today,” his mother explained. “If there are no mandlen, there is no Shabbat,” he said before blowing out the Shabbat candles. This story, which was retold many times over the years, made him infamous throughout their Jewish community.

It was after the book burning that the Germans forced the Jews to create a Judenrat, an administrative body of Jews who had to ensure that Nazi orders and regulations were implemented; Judenrat would eventually be established in Jewish communities throughout Europe. One of their first tasks was to round up Jews for daily work assignments. Women in Maciejow were often selected for gardening and cleaning tasks; men were typically selected for hard labor, or to make crafts that were useful to the Germans.

Pesel was assigned to weeding one of the vegetable gardens at German headquarters, which had been established in the former Catholic Monastery—the same place where the Red Army had been stationed. When she didn’t return on time one afternoon, Noike decided to track her down.

“Pan, excuse me!” Noike called to a young guard standing near the vegetable gardens, smoking a cigarette. Pan was the customary way to address a man as “Sir”; women were addressed as Pani. “Where are the garden workers?”

“They went home for the day,” he explained, tilting his head back as he blew a puff of smoke into the air.

“But my mother isn’t home yet,” Noike said.

“She might be inside the main building—they took some people for an additional assignment,” the guard nodded towards headquarters.

Noike was friendly with the Polish gardener, known as an ogrodnik, who took care of the orchards next to German headquarters and lived in a small house on the property. The gardener sometimes asked Noike to deliver a basket of his best apples and plums to the Commandant. Noike would try to appear calm when he entered the Commandant’s office; the vicious German Shepherd, who they called Ivan, was always at the Commandant’s side. With an angry look, the Commandant would grab the basket and wave the little Jew away.

Noike took his usual route that afternoon, slipping through the back entrance and then heading towards the long staircase that led into the main building. Walking up the stairs he passed an older soldier who was on his way down.

“Where do you think you’re going?” the soldier asked.

“My mother is working here—I want to find her,” he explained.

“No, no—you can’t go in there,” the soldier snapped. “You go home now, young man, your mother will be home soon,” he said, handing him a little harmonica.

The soldiers were humiliating the Jews inside, forcing the men onto all fours and then making the women ride them like horses. They took particular pleasure in harassing an overweight man, whipping him as he crawled on the floor. The Commandant unleashed his German Shepherd on this man and many others. All of these events were filmed with one of the hand-cranked cameras, entertainment for the people back in Germany. Decades after the war one of Noike’s aunts told him about the film and how his mother had been forced to participate. His mother never mentioned what happened.

Later that summer, Noike was playing outside when he heard a crowd gathering in the main square. He recognized hundreds of his neighbors—men whom he used to see praying at the synagogue, shopping at the market, or strolling in the square—surrounded by SS and Gestapo (Nazi secret police) wielding machine guns. All of the Jewish males between the ages of sixteen and sixty had been ordered to turn in their Russian passports and get German ones. The men were forced to line up in rows of ten and marched off to German headquarters.

Noike saw the fear on their faces and ran home.

Years later a survivor told him what happened when they passed through the gate at the German headquarters. Both sides of their path were lined with Gestapo holding sticks the size of baseball bats. The men were pushed through and beaten severely; big German Shepherds gnawed at their heels, tearing their flesh. One of the Gestapo used his stick to start dividing the men into two groups: men who possessed certain craft skills—tailor, shoemaker, harness-maker, carpenter—were told to run home; the remaining four hundred were taken behind the headquarters and shot.

The Germans told the Judenrat that these men were sent to a labor camp and would return in one year. Within days, the families received letters from their loved ones, saying they were working hard and they would come home soon. The families did not have to examine the letters very closely to realize that someone other than their husband, father, uncle, or brother had written them. Noike also knew better: he saw the young Ukrainian laborers walking from headquarters with shovels; he heard the gunshots from his home.

A tombstone now marks this place.