Читать книгу Empire Girls - Suzanne & Loretta Hayes & Nyhan - Страница 8

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 2

Ivy

I DIDN'T KNOW how to grieve.

While the undertaker began discussing finalities with Rose, I sneaked out the back door. The weather was pleasant, and I imagined my father throwing up his arms as he always did on the warm days of late spring, shouting, “aces-high in the ever-loving sky!” to the blinding sun. The garden he’d recently turned ran wide and deep, leading to a freshly planted field of barley. Beyond that, the road beckoned, the one leading to Albany, and beyond even that, New York City. After squelching the urge to hitchhike, I stretched out across the damp grass and tried not to think about the sound of the casket being transferred to the waiting hearse. The ground held the trace of a chill, and I shivered, closing my eyes as the cold seeped into my dress. What would it feel like to sink into the endless earth? To never feel it under my feet again?

“It’s time to leave, Ivy.”

I blinked up at my sister. She wore a dress she’d sewn the night before, a prim, black buttoned-up number that covered everything but her face and hands. Rose’s eyes were puffy and raw, and her soft blond hair was twisted into a tight, unforgiving knot behind her head. I wished she’d let it loose, unfurled like Rapunzel’s rope. I could climb it up to the bright blue sky, leaving this awful day behind.

“Do we have to go now?”

She frowned. “I’m going to pretend I didn’t hear that.”

The sun’s rays kissed the top of Rose’s head. I didn’t want to do anything but watch it shimmer. “You should let your hair down,” I said. “You’d feel the breeze if you did.”

Rose grasped my shoulders and pulled me to my feet. “I’m not sure where your mind is at, but the undertaker is ready for the procession to the cemetery.”

Procession? The few mourners from town—some clients of father’s and the odd academic or two—had departed once they’d satisfied their morbid curiosity. Our neighbors, respectful of our privacy, left sandwiches and canned asparagus at the back door, along with a prayer card. I preferred their method.

Rose brushed the dirt from my dress and guided me toward the hearse parked on our cobblestone portico. Dressed in black suits, the undertaker and his men rushed about like a flock of Poe’s ravens, flittering in and out of the house, opening and closing doors, ushering us into the hot cocoon of the hearse’s inner cabin. I immediately opened a window and stuck my head into the spring air. Rose kept her window closed and turned her back to the glass.

The car moved slowly through downtown Forest Grove. We passed the grocery, where Mr. Madden was sweeping the entryway. He stopped and saluted as our sedan passed.

“Does he know father wasn’t in the armed forces?” Rose asked. I nearly jumped a foot when she said it. I hadn’t noticed she’d moved so close to me.

“I don’t think he knows what else to do.” I saluted him back.

We passed the butcher, the watchmaker, the cobbler—the three men standing in front of their establishments, heads bowed as we lumbered by.

Rose leaned forward to get a better look. “Are they praying?”

“I think so.” A lump formed quickly in my throat. Father had been an eccentric presence in town, but never failed to offer a smile and a tip of the hat to every soul he encountered. They remembered him, and their tribute touched my heart. I twitched with the unexpected desire to embrace the entire town.

We turned down Plum Street, just blocks from the graveyard. Mrs. O’Neill herself stepped out of O’Neill’s Coiffures. Father brought me to her salon the previous fall, where I sat perched at the edge of a lavender stool while the old lady bobbed my hair with a ruler. I’d asked her to make me look like Clara Bow and she didn’t bat an eyelash, humming “Ain’t We Got Fun” the whole time she had the scissors at my neck. I waved and called to her.

“This isn’t a parade,” Rose muttered. She retreated to her dark corner of the cabin.

“But it is,” I said. “Open your window and have a look behind us.”

Mrs. O’Neill joined a group following the hearse on foot. I spotted Mr. Madden, white starched apron still tied tightly around his waist, and Mr. Lawrence, father’s solicitor. He seemed to have come out of nowhere. Mrs. O’Neill offered him a quick smile, and he took her arm.

“Do you think they’ll come back to the house afterward?” Rose asked, worrying at her lower lip. “I don’t have enough to feed everyone. If I’d known we were hosting a reception, I would have made a casserole.”

“Why can’t you just take it for what it is?” I gently chided her. “Don’t you understand? They’re part of father’s legacy.”

The driver rounded the entrance to the small cemetery and parked in full view of the dogwood tree we’d planted next to mother’s grave. It had just begun to bloom, the flowers bursting pink and white as newly hatched chicks. The air smelled fresh, and the bright green grass seemed painted onto the rolling hills by an impressionist’s hand.

The beauty was an insult, an affront.

Rose took a deep breath. “It’s so pretty today.”

“Then why does it hurt my eyes so much?”

Before she could respond, the townspeople caught up with us, and we all walked over to where the men were finishing up their digging. I could hardly look at the upended earth.

We had no minister, but no one seemed to mind. The undertaker said a few words, and townspeople formed a line to pay their respects. They patted our arms and shared quick remembrances. And then they were gone.

It was time to lower our father into the ground. Rose stepped forward, but then she whipped her head around, her expression panicked. “I forgot the flowers to toss. We have nothing to send him off, Ivy.” She began to cry. “How could I have done that?”

“It doesn’t matter,” I said. “Please, let’s just go.”

Rose wiped under her eyes with trembling hands. “It’s tradition. We did it for Mother, and we’ll do it for him. Don’t you want to say goodbye properly?”

No, I wanted to scream. I don’t. Instead, I snapped a few branches from the dogwood tree, careful to keep the blossoms intact. “Here,” I said, handing them to her. “Now you won’t break with tradition.” I turned, unable to watch, and walked back to the hearse.

A tall, lanky man leaned against the hood, deep in conversation with the undertaker. When I approached, I realized it was Mr. Lawrence. He noticed me and straightened up, removing his fedora. In the sunshine his hair was the color of burned oatmeal, and the smattering of freckles on his nose made me want to hand him a tin can and send him down the road to kick it.

“My condolences, Miss Adams,” he said, dipping his head.

“You said that already.” I liked that both men looked away, my sharp words making them uncomfortable. An anger had flared inside me, hot and destructive, burning away the last of my courtesy. I glared at them.

The undertaker excused himself and escaped into the car. Mr. Lawrence and I leaned back against the sedan, watching Rose as she bent to place the flowers on my father’s casket.

“So what it is?” I asked. “Is it money? Gambling?” I paused, my heart lifting ever so slightly. “Did he sell a book?”

“It concerns your father’s estate,” Mr. Lawrence said, staring at the damp ground. “I’d like to speak with you and Rose privately. We could go to my office, or I could accompany you home.”

“From the look on your face, it ain’t good news. Why not spit it out right here?”

“Your sister should be with you. Your father expressed concern that you two aren’t very...close.” He stepped in front of me, blocking my view of Rose as she began to tidy up mother’s grave. “Today, it’s necessary to bridge that chasm. I don’t mean to frighten you—”

“You’re doing a pretty good job.”

“But these things are never easy, and your father was an unusual man.”

“He was a good man.”

“I know,” he said. “I didn’t mean to imply otherwise.”

“Just so we’re copacetic.” I felt something on my cheek and swatted at it. It was a tear.

Mr. Lawrence reached into his pocket, pulled out a clean handkerchief and handed it over. “I have a poor memory for quotations, but there are a few that stick with me. I’ve got one I think you might know. Do you want to hear it?”

“I’m going to anyway, right?”

He reddened and cleared his throat. “‘For in that sleep of death, what dreams may come.’”

“Hamlet,” I said quickly. I knew Shakespeare’s plays inside out and upside down.

“It always appealed to me because of its optimism,” Mr. Lawrence explained. “It doesn’t have to be the end, Ivy,” he added gently. “Not entirely. I believe those who’ve passed on still have a stake in our affairs from the other side.”

I nodded, unsure of how to respond to his kindness. The thought did provide some comfort, but it wasn’t until we were riding home, the three of us silent in the shadowy cave of the hearse’s cabin, that I realized he’d misinterpreted Hamlet’s words. The dreams of the dead were not of the living, they were of regret for the sins of life, the unfinished deeds, the mistakes that could never be fixed.

* * *

We convened in father’s study. The afternoon had grown chilly, and Rose started a fire and fixed some tea. I should have helped her, but once I’d settled into father’s comfortable leather chair, I didn’t want to move. I could still smell the last cigar he smoked.

Mr. Lawrence drained his teacup and placed it on the mantel. He refused our offers to sit and began to pace, file folder in hand. “Your father lived a colorful life before marrying your mother. I suppose I should start there.”

Though I didn’t like the idea of father telling Mr. Lawrence his secrets, the care with which he chose his words bothered me more—he knew what was to come next would be distressing. I glanced over at Rose. Her pale face and wide, fearful eyes meant she’d come to the same conclusion.

“Go on,” I urged.

Mr. Lawrence stopped moving, took a breath and looked at me directly. “Your mother was your father’s second wife. His first marriage produced a son, and your father has left the management of his estate to this man.”

“That can’t be true,” Rose said after his words sank in. Her voice sounded weak and faraway.

“I don’t understand,” I added. “Why would he have kept something like this hidden?”

Mr. Lawrence placed the folder on my lap. “I’m not certain. I’ve only just learned of it. Perhaps you should read this, and then we’ll proceed.”

Rose got up and sat next to me, and I placed the document between us. I read through it a few times, but the repetition wasn’t necessary—for something that would change our lives so irrevocably, it was remarkably straightforward.

In his beautiful handwriting, all measured slopes and perfect loops, our father had clearly communicated his wishes. He’d left the management of his estate to this man, a son he’d sired six years before marrying our mother. Asher John Adams. It was an untouchable name, mysterious with a dash of history, and so naturally one my father would choose. To my surprise I felt a stab of affection for this lost half brother, the unending possibility of him stretching my imagination. I pictured him dark and mysterious, with a certain Valentino exoticism. I’d studied the great actor in the theaters of downtown Albany, memorizing the way he crushed his eyebrows and widened his eyes at the same time, the magnificent strength as he folded his arms, muscles rippling. My brother would look like that.

Asher. Was he a gift from the grave? “When can we meet him?”

Rose gasped. “Ivy, please take this seriously. This is our house. Ours. Father’s mind must have been compromised.” She sat forward, appealing to Mr. Lawrence. “Can you provide proof? How do we know some swindler didn’t concoct this scheme? Where is this first wife? How do we know this man is father’s son?”

“If you’ll sift through the file, you’ll find the necessary documents,” Mr. Lawrence said. “I looked them over closely this morning. I think they’ll settle any question of legitimacy.” He touched the open file with his finger. “Please remember that seeing things in black and white can be a shock,” he added, his voice a touch softer. I knew he wasn’t warning me. It was Rose who’d gone still.

I began sifting through the memos from the bank, threatening letters from the state assessor’s office and countless hastily scribbled notes in my father’s handwriting. Asher’s name appeared periodically, with no other information than his birth date. April 29. Mine was May 1. Had father thought about him when I came into the world? He must have. I felt a constricting of my chest. Was it a pang of loss or anger or sadness? I shook it off.

“And Asher’s mother?” I asked as I continued rummaging through the paperwork. “What of her?”

“Deceased,” Mr. Lawrence said, frowning. “There are no other known relatives.”

I’d almost exhausted the file when I spotted our brother. As large as a letter, it took a minute to register as a photograph. “It’s him, Rose.”

The photograph had been enlarged and cropped, and I stared into his extraordinarily light eyes. They were Rose’s eyes. In fact, he was the male embodiment of Rose— aquiline nose, lean frame, full mouth. He was in shirtsleeves, arms crossed, the thickness of his forearms hinting at manual labor. The half smile cocking his mouth was a brash challenge hidden under a thin layer of civility. A metal plate lay tucked behind his left shoulder. It was stamped with two words: EMPIRE HOUSE.

“He could be your twin,” I said, trying not to sound as disappointed as I felt. I’d sat across from Rose at thousands of family meals. Though good-looking, Asher’s features were as exotic as a jar of strawberry jam. I thought at the very least he’d look like an outsider, different, like me. “He is definitely an Adams,” I admitted. “No one can deny it.”

“He’s still a stranger,” Rose said in a choked voice. “If he wasn’t, he would be here, wouldn’t he?”

Mr. Lawrence sighed. “There lies the problem. Asher John Adams seems to have vanished from the face of the earth. It appears your father had very little contact with his son over the years, no more than a handful of terse phone calls. When your father wished to finally speak to his son in person, he learned Asher Adams has no known address in New York City or the whole Eastern seaboard, for that matter.”

I didn’t like that. Was Rose right? Had my father been swindled? No. He could be flighty, but he was too intelligent for that, too sharp-minded. “Yet, something in those conversations convinced my father to make Asher manager of his estate,” I said. “He could have given it to Rose or me, or even you.”

“I’m not the eldest anymore,” Rose said. “But I am here, and he isn’t.” Her posture regained its straight line. “Could the problem be solved that easily? If we can’t find him, everything stays as it is?”

Mr. Lawrence looked pained, indecision clouding his hazel eyes. I stared at him, mercilessly, as he waged debate within himself. How he must tip his hand in the courtroom! I began to wonder why father picked this man. Then it hit me, his fee was probably right next door to nothing. I glanced down at the bank notices. “There are further financial complications,” I said evenly. “Could you explain what those are?”

He nodded. “The mortgage and property taxes are in severe arrears. If the heir does not make claim on the house and bring the tax bill to date, the home will be sold and the bank and state will see its money.”

“Did my father leave any funds in his accounts?” Rose asked, though we both knew the answer to that one.

Mr. Lawrence paused. “I’m sorry, but not very much at all.”

My mind reeled, the implications of this development still unclear. “What if Mr. Asher John Adams can’t be found? What happens then?”

“If he doesn’t come forward within a year, the house will revert to the bank,” Mr. Lawrence explained, his tone regaining a professional aloofness. “The bank will pay the property taxes and sell the home as soon as they can get the stake in the ground.”

We were silent a moment as we considered that image.

“What if we could raise the funds?” Rose said, growing desperate. “Could we pay the bank in installments?

Mr. Lawrence looked away. “I’m afraid you’d need Mr. Asher to approve that route, Miss Adams.” He pitied us. I hated pity. It was a thin veil hiding the firm belief that a similar fate could not possibly happen to him. “Your father was in the process of finding Mr. Adams when he passed on. He’d begun searching in New York City, but hadn’t gotten any further.”

“Could we hire one of those private detectives?” Rose asked. “That seems the logical route.”

“Of course,” Mr. Lawrence agreed. “However, there is the matter of the fee. Pinkerton charges a thirty-dollar per diem, expenses not included. New York is not an inexpensive town.”

Rose slumped in her chair. “I see.”

“I’ll go,” I volunteered.

Mr. Lawrence cleared his throat. “I don’t think it wise to go alone, but if you went together, you might find Mr. Adams quickly and we can get this sorted out.”

Rose stood and tugged at her shirtwaist irritably, displacing her black silk belt. “We’re supposed to pick up and go to that awful city and allow a stranger to make decisions about our future?” she said, shaking her head. “I can’t, Ivy.”

“Can’t what?”

“Allow any of this,” she said, rising. “I know you’re not accustomed to it, but listen to me for a minute. If we continue to let our life fall away, piece by piece, we’ll be left with nothing.” Her eyes filled and brimmed over, but she didn’t brush at her cheeks. Tears had already replaced our home as Rose’s most constant companion. “There must be something we can do to keep the house. I can get a job, two even. We have a year, don’t we?” Rose asserted, her voice gaining authority. “You just said it.”

“Most men don’t make that sum in a year’s time,” Mr. Lawrence said gently.

“But we’re women, Mr. Lawrence,” I interrupted. “Unless you hadn’t noticed.”

He reddened, and I decided to take advantage of his discomfort. “I can’t shake the feeling we’re not getting the whole story,” I said. “Is that true, Your Honor?”

He looked away. “I’m not a judge.”

“You’re sure acting like one. Why not tell us everything?”

“Ivy.” Mr. Lawrence met my eyes. All the wavering had disappeared from his, and now they bored into me, direct and clear as a midsummer’s sky. “I don’t enjoy bringing bad news. I hope you understand that. Any decent person would be concerned about the sheer number of revelations it’s become my responsibility to impart.”

“Revelations aren’t meant to be experienced piecemeal. I assure you very little shocks me. Please continue.”

The corner of his mouth twitched, and he glanced quickly at Rose. “Bankers are not patient men. Eviction proceedings have begun. I paid a visit the other night to tell your father of the bank’s decision. I’ll never forgive myself for adding to his misery.”

“It’s not your fault,” Rose said automatically, but something tore inside her, a messy, ragged break. She covered her face with her hands and really let go.

Mr. Lawrence looked as helpless as I felt. I knew I should comfort her, but I hesitated. And as I crouched down, she lifted her head, and I knew I was too late. There was something new in her eyes, a coldness that frightened me a little. “I’m going with you to New York.”

“You haven’t been past Albany,” I said to my sister, but not unkindly.

“Neither have you.” She sniffed.

“I’ve been to the city a thousand times in my mind. That counts for something.” I was meant for Manhattan; Rose was not. The city would find a thousand ways to hurt her, one sucker punch at a time. I picked up the photograph of Asher. “Look at how he’s standing, like the devil himself. Let me go first and see what we’re getting mixed up with.”

Rose snatched the photo and held it at eye level, as though she was speaking directly to him. “This man is my brother,” she said, her voice steely. “It can’t be denied. He won’t take the house, not after seeing me.”

“Is it that important to you, to keep the house?” It was a roof over our heads, nothing more. A prison, even. Rose was already too old to be living at home, and I was determined not to follow in her footsteps.

“Yes,” Rose said. “I’ve built my entire life around this house. It’s all I have, and we both know it.”

I couldn’t argue with that. Rose needed something tangible to prove her worth in the world; I had what was in my head. My father had given that to me, and only me. Guilt wasn’t something I experienced often, but I could recognize it. “We’ll find Asher,” I promised, taking the photograph from her hands. I held it up to Mr. Lawrence. “Where did you get this?”

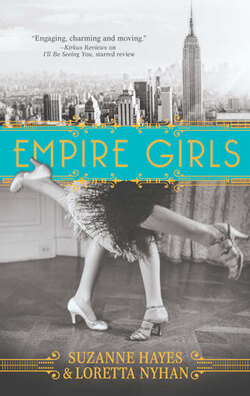

“According to your father, the photograph was sent to your house approximately eighteen months ago,” he explained, obviously relieved I’d asked a question he could answer. “No return address. Empire House is a boarding hotel for women, so either he knew someone who lived there or the spot was chosen at random.”

“It’s a start,” I said, growing excited at the prospect of traveling to the city. Empire House sounded grand. I pictured ladies in their finery, sipping gin rickeys on the sly and admiring each other’s diamonds. “We’ll send a telegram to let them know we’re on our way.”

Mr. Lawrence reached into his suit coat pocket and extracted a white card. “My address. Please write to let me know you’ve arrived safely and keep me apprised of whatever you find. I’ll see what I can do from here.”

We both knew that was nothing much. I added his card to the folder and tucked it under my arm. “We’ll keep in touch,” I said as he took my hand. “Thank you.” When it was Rose’s chance to say goodbye, Mr. Lawrence returned to his valise. He lifted a small framed drawing from it, an India ink rendition of a single rose. “Your father admired this when he visited my office, Miss Adams,” he said, handing it to my sister. “I’d like you to have it.”

“That’s very kind of you,” Rose said in a small voice.

Perhaps I’d misjudged Mr. Lawrence, I thought as I watched Rose hug the frame to her bosom. Given his closing argument, he was probably quite good in the courtroom.

“I suppose we can’t blame him,” Rose said after he left. “He does seem a decent sort of person.”

“For a solicitor,” I muttered. We stood there in silence, neither of us moving. I had no idea what Rose was thinking, but I had only one thought: let’s get started. I gestured toward the drawing. “Should we put his gift on our wall, even if we only own it for another few hours?”

She smiled bitterly at my choice of words. “All right.”

Father frequently changed the paintings on the walls in his study, leaving a hodgepodge of bare nails and crooked frames as a result. Though I admired his work, the sheer volume made careful scrutiny impossible. As I scanned his makeshift collage, looking for the perfect spot to hang Mr. Lawrence’s drawing, my eye fell on a small painting I was certain had been gathering dust for years. It featured a woman holding a wiggling toddler. Blonde and pretty, she stood on a stoop in front of an imposing brownstone, a copper plaque half-hidden by the child’s flailing arms.

“Rose, bring that photograph of Asher over here.”

She did, and I held it next to the painting. The door, the plaque—it was Empire House.

Rose squinted at the two. “I suppose I should send that telegram right away.”