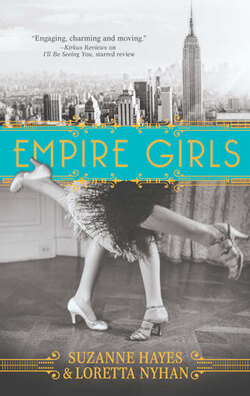

Читать книгу Empire Girls - Suzanne & Loretta Hayes & Nyhan - Страница 9

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 3

Rose

WE RECEIVED AN answer from Empire House two days after Ivy sent the telegram. She’d come running up the driveway and into the kitchen, bringing the spring morning behind her like a trail of hope. I was pressing her dresses in the kitchen, where I’d set up an orderly “Packing Station” so that we wouldn’t bring too much or too little. We could only bring the most necessary items, and the rest of our things would be sold lock, stock and barrel with the house if I did not succeed in New York City. Choosing what to take and what to leave behind was more of a chore than I’d anticipated, and soon I wanted to bring nothing at all.

“You haven’t had your toast, Ivy.”

“Who cares about toast! We’ve gotten our rooms, Rose! Listen...

“‘Dear Ms. Adams,’” began Ivy, reading me the letter and pacing back and forth with excitement.

“Did you want tea, Ivy?”

“No...I don’t want tea. Would you listen?”

I nodded.

“‘Dear Ms. Adams,’” she began again.

“‘Though it is not our usual rule to lease space to young women we have not already met and interviewed, it seems you are in luck. We’ve had a recent vacancy here at Empire House, making room for you and your sister. Please be advised that the accommodations are modest at best. If you do not arrive within the week, we cannot assure the room will be available. Please send a telegram on the day of your arrival, so we may prepare. Note, as well, that if we deem you unsuitable, you will be denied occupancy. Please send us your arrival date, and we will have a driver waiting for you at the station.

Nell Horatio Neville (Proprietor of Empire House)’”

“Not very warm, is it?” I said, misting a cotton nightdress with water.

“It is the city, Rose. I swear, you are so...so...”

“What?” I asked.

“Pedestrian...”

Then she ran off again. She’d been spinning in circles since Father’s funeral. I had, too, only my circles were in my head, while Ivy seemed to be walking on a cloud.

I was worried.

I put the hot iron back onto the stove and sat at my kitchen table folding father’s shirts. I was going to give them to Mr. Lawrence, but I wanted them to be tidy. It was the proper thing to do.

I knew Ivy was devastated by our father’s death. We both were. But when Lawrence gave us the news...the unspeakable news about Asher, Ivy seemed to forget all her sorrow. Part of me was glad that she had a diversion. Glad that her dreams of living in The City were coming true. I knew that eventually she’d fall back into grieving, but her excitement set me free to take care of my own sorrows.

I’d lost my father, my house and my future. It was a quiet loss, one that no one seemed to notice.

I wasn’t going to New York City to throw myself into Asher’s arms. I was going to New York City to find a stranger, make a great deal of money and get him to sign my house back over to me.

I knew the resemblance could make the difference in allowing him to accept us. Ivy didn’t seem to be at all worried that, once found, Asher might not want to have anything to do with us. I feared her romantic, theatrical view of life was clouding her view of reality. Our father had raised us...not him. Was it not fair to assume he might want to avoid being found at all? That he might resent us? I didn’t mention this to my sister. In truth, as Ivy hid from our father’s death inside a bubble of expectation and hope, I hid from it by convincing myself I’d slipped into a new narrative. I couldn’t help but think we’d been thrust into a Dickens or Austen novel almost overnight. It kept me separate...it kept me curious instead of dead inside. When we found him—if we found him—he would not be able to turn his back on me. No good character can walk away from another who could be their very twin. It’s the denouement of all great mysteries.

Father always said that “Everyone has an inner narcissist....” I would be his conscience, and Asher would sign my house over to me. If you understand a bit of human nature, and don’t overestimate people, getting what you want is simple enough. I knew I could get the house back if we found him. The question was, how would we find him?

I picked up one of father’s shirts and held it against my face.

“I don’t want to believe you did any of this on purpose. I want to believe you thought you were protecting us somehow. But from what? Oh, Papa!”

I wanted him so badly at that moment. I wanted him to come into the garden and have tea and toast. I wanted to tell him of the horrible dream I’d had. Nothing seemed real.

It occurred to me that grief is like a tunnel. You enter it without a choice because you must get to the other side. The darkness of it plays tricks on you, and sometimes you can even forget where you are or what your purpose is. I believe that people, now and again, get lost or stuck in that tunnel and never find their way out.

I had no intention of doing that. I’d leave myself notes in my pockets saying, “Father is dead,” if I had to.

I got up from the table quickly, held back my tears and packed the rest of Ivy’s dresses.

* * *

Later, I was sitting on our front porch, reading, when Ivy came and sat at my feet.

“It’s like he left us a present, Rose. Papa gave us one last adventure. I can’t tell you how that comforts me,” she said, a dreamy look in her eye.

“Did you know about him?” I asked.

“Know about who?”

“Did you know about Asher? Did father tell you on one of your trips? I know you two had your own language. Be honest, Ivy. I need to know.”

She stood up, her face red and angry. “No. I didn’t know. Do you think I could have sustained this whole charade? Do you think so little of me that I would have kept so large a secret from you? Honestly, Rose...sometimes I think you don’t know me at all.”

Then she stormed back in the house.

I followed her inside. My whole world was bobbed, like Ivy’s hair, at bold angles. Very little was making sense, so I did the proper thing. I made supper.

* * *

A few foggy days full of packing and planning passed. Ivy flitted around, but I wasn’t surprised. I saw her at breakfast and at dinner. She must have been wandering by the lake, because she’d come home disheveled and muddy. If she’d chosen to grieve alone, it would have been nice to let me know. As it was, I thought she was simply running away again.

I was surprised at how easy it was to empty the house of our personal belongings. Life is much more fleeting and changeable than I’d thought.

I was the one who sheeted the furniture and put the better china in the secret attic space. I was the one who got the locksmith to put dead bolts on the doors. I was the one who rang Mr. Lawrence when we knew the date we were to leave. And it’s a good thing I did, or we would have had to drag our trunks to the station.

The morning Ivy and I left for New York City, Mr. Lawrence came to fetch us.

“How very gallant of you, Lawrence...but I’ll walk. I feel as if the air would do me good,” said Ivy. “Besides, I’ve always had this vision of myself walking down the road without turning back. I’m no Lot’s Wife. Not me.”

“Would you like to make sure you have everything you need, Ivy?” I asked.

“You are the most organized person I’ve ever met, sister. I’m sure I’ll be all set.” Then, with a quick nod to Lawrence, and a “See you on the platform, Rose!” to me, Ivy left for the train station where she would send the telegram to Empire House letting them know what time we’d be arriving, and purchase two one-way tickets to New York City.

“Father babied her, and now I’m going to have to make sure she doesn’t get ruined by New York. She really is impossible,” I said.

“I know it isn’t my place, Rose. But do you think you could learn to trust one another, you and Ivy?”

“Trust her? You must be joking. Have you sat too long in the sun?”

“Would it make a difference if I told you that your father mentioned he wished the two of you were closer?”

“Are you hiding something, Lawrence? Because if you are....”

“Let’s go, Rose. I’d hate for you to miss your train,” he said, saving me from trying to conjure up an empty threat.

As he started his motorcar, I walked through the house one more time. Saying goodbye to it. “I’ll come back to you,” I said. But it didn’t answer me, the house. It felt hollow, and its hollowness hurt my soul.

* * *

I found Ivy sitting on a bench at the very end of the platform.

“Hiya!” she said, getting up to greet me.

“You didn’t even say goodbye to Mr. Lawrence. You can be a very self-centered girl,” I said.

“I don’t like anything drawn out—you know that,” she said, melting back onto the bench, slouched over. I sat next to her as tall as I possibly could.

“I’m afraid your dress may make the wrong impression when we finally meet Nell Neville,” I said. She was wearing a purple satin drop-waist dress with a beaded fringe. The back fell into a deep V and the front exposed more neck than I wanted to look at. Her stockings were showing, and her shoes were black heels with a small strap, showing the top of her foot as well as her ankles. She was as good as naked.

“No, Rose. You are the one who will make a poor impression. I told you to leave those clothes behind. You look like a servant or an old lady. Either way, it’s not good. Plus, you’re going to sweat to death in The City. No lake breeze there, honey.”

She threw one of her legs over the iron arm of the bench and leaned into me.

A train far off in the distance sang its song. Ivy bit her nails. “When we were little you loved that sound,” she said. “Did you know that? We used to lie in bed together and play that game ‘Where is it going?’ and then we’d make up fantastic adventures.”

“Don’t bite your nails, Ivy. It’s a childish, unclean habit.” I said, not acknowledging her memory, even though I did, in fact, recall it.

She looked at me and smiled. A true, infectious smile, one that always softened any roughness I felt toward her. Ivy has that affect on people, causing whiplash of affection. “Darling, of course I remember,” I said. “I’m just not in the mood for memories right now. Tunnel of grief and all that.” She nodded her head and sat back up.

On that platform, with my high-laced boots crossed at the ankle, and Ivy slinking lower down on the bench every second, all I could do was read my copy of Edna St. Vincent Millay’s A Few Figs From Thistles. I especially liked the poem entitled “MacDougal Street,” though it made me cry.

“He laid his darling hand upon her little black head,

(I wish I were a ragged child with ear-rings in my ears!)

And he said she was a baggage to have said what she had said;

(Truly I shall be ill unless I stop these tears!)”

I clutched the book to my breast and hoped against hope that Empire House wasn’t anywhere near MacDougal Street.

* * *

Ivy settled in by the window on the train. She had father’s leather rucksack on her lap and kept buckling and unbuckling the straps. She was quite talkative, which was different than usual.

I was hoping she’d sleep on the train and I could read. Ivy slept when she was excited about something she had to wait for—she was always the first to bed on Christmas Eve. But as she spoke, I began to understand that she was as nervous as I was about the trip. I found myself worrying about what the city would do to her. It never once occurred to me to worry about myself. My objective was clear: find Asher, convince him to sign the house over to me and get a job to acquire the money to pay the back taxes on our home. And I told her as much when she asked me.

“Aren’t you the least bit curious?” she asked, frustrated.

“I wouldn’t be human if I wasn’t, Ivy. But please remember, I don’t intend to get involved in any sort of life once we get there. I plan on finding work, finding Asher and then finding my way home. What you do after all is said and done is your prerogative.”

“So you’d just give up whatever life we make for ourselves, and return to that desolate place?”

Desolate?

I leaned across the narrow space between us and took her chin too sharply in my hand. “Have you ever even considered that as you made your life plans, that I was making plans of my own? Or did you think I was an empty-headed fool who lived to serve you and Papa?”

She yanked her face away and leaned her forehead against the window.

“I suppose I thought you’d... I don’t know. Did you? Did you have plans?”

“Of course I did. My plan was to live quietly at Adams house until I died. That sounds terrible to you, doesn’t it? A wretched sort of existence. But let me tell you something, Ms. Ivy Adams. As we grew older, the fact that I would not marry was not lost on me. How could I? Who was I to meet? I thought you would finally get up the courage to leave Forest Grove, and I would look after Father until he was an old, old man. I would be the keeper of our traditions...I would be a safe harbor for you, if you ever needed anything. And I would always have the house. And just look at the both of us now. Our father died too soon. He left us with lies, secrets and no money. I no longer have the peaceful future I set out for myself. And yet? Here we are! On our way to YOUR future. So, to answer your question...YES. I would return to that desolate place. Because that was my dream.”

Ivy took a moment to respond. I could almost see the thoughts brewing behind those lovely eyes of hers. I could see her deciding whether to be mean, or sarcastic or simply honest. In the end, she chose humor.

“Well, now, Rose. That was quite a monologue. I should note that down. Really. I’m not kidding...you’d be a good writer I think. You read enough. Have you ever thought of that instead?”

“And you, Ivy, would make a good politician,” I said. I had to smile at her. She could have lashed out at me, but she chose not to.

“I think I’ll read my book now, if it’s not too rude,” I said.

But I never got the chance, because we’d already arrived at Grand Central Station.

* * *

“Come, let’s get the trunks,” I said as we disembarked.

“No, you get them. I’ll go find the driver they sent from Empire House.”

She ran away from me quickly and was swallowed by the crowd.

“Ivy!” I yelled, climbing back up the steep steps of the transom, trying, in vain, to catch a glimpse of her, and holding my hat against the hot, smelly air that came flying at me like the breath of a beastly giant.

I was pouring sweat already, and my lace collar—the one Ivy’d begged me not to wear—was sticking tightly to my neck. I was choking, probably to death, and I’d already lost my sister.

“Here you go, ma’am,” said a young man who’d taken my trunks from the luggage car.

“I say, are you planning on helping me get these trunks through the station and out...side?” I had no idea where I was going.

He held out his hand, and when I went to shake it, a man pushed passed me, laughing. “He wants a tip, not a handshake... Country girls, I swear, you’re all knee-slappers.”

Our money was so limited that I wasn’t going to waste it on handouts. Chivalry should be free, anyhow. So I looked at the trunks and convinced myself I could do it on my own.

I shook my head at him and tried to politely explain why I was not filling his hands with coins. Only no one could hear anything over the din of voices, the steam and chaos. I reached down and placed my gloved hands on the straps of each trunk, stooped over and began to drag what remained of us through the station. I can only imagine what I looked like. Finally, I saw the glass doors ahead of me, and I saw Ivy in her purple satin dress with the beads at the bottom shining in the sun. I wasn’t upset she’d worn it anymore. I’d be able to find her anywhere.

I lurched outside banging the trunks against people and bricks and anything that got in my way.

She was leaning against a black sedan, but it was the driver who saw me first. There was a sign taped to the passenger window that read EMPIRE HOUSE.

For some reason, it was that sign...affixed haphazardly to that dirty window that brought the whole ordeal into focus. No longer was this some foggy, dark dream. This was my life, and I was suddenly very present in it. Nothing was going to fit neatly into the pages of a book. Life, it seemed, was busy, and messy and loud. Everything about this city was so loud.

Ivy turned to look at me, following the driver’s gaze, and put her hand over her mouth. She laughed so hard I thought she’d lose her breath.

“Thank you ever so much for the help,” I said, trying to push my hair back from my sticky forehead.

“I know how much you like hard work,” she said as she came to me and took the trunks a whole three steps to the waiting automobile. “But I never considered you would try to become a mule. Why didn’t you let the porter take these?”

“Because he wanted money.”

The driver took the trunks from Ivy and opened the door for me.

“Thank goodness, a gentleman,” I said as he held out his hand, I thought, to escort me into the cabin of the car.

I started to place my hand on his palm, but he pulled it away. “Sorry to disappoint, miss, but I was sorta askin’ for a tip,” he said.

“Are you going to embarrass me every single day of my life, Rose?” asked Ivy as she reached into the outside pocket of Father’s bag and pulled out a few coins. She dropped them in his hand, slid into the sedan next to me. Then she batted her eyelashes, which made him smile at her. The whole flirtation happened practically in my lap, forcing me to lean back so that their hands didn’t touch me by accident.

“What’s your name, fella?” asked Ivy.

“Jimmy, doll,” he said cocking his hat to one side. He was darker, this Jimmy. “Black Irish” Mother used to say, when we were impressionable young girls. She’d say it with a bit of disdain when we’d see them in town. Wrong side of the track kind of people. We Adamses didn’t belong on the track at all, so we could always identify people on, off, on the right side or the wrong side of any situation. Father said it made us well rounded.

“Do you have a name?” he asked my sister.

“Ivy,” she said. “I’m Ivy and this is my sister...”

Jimmy cut her off. “Ivy, huh? You don’t look like something stuck to the side of a house. I’ll have to come up with another name that’ll suit ya better.”

As if he’d see her again. Not to mention he hadn’t wanted to know my name, which is when I realized that if anyone could become invisible in a city full of people, it would be me. That thought brought me back around to thinking about Asher. If it was true, and we were similar people, then perhaps he was invisible, too. I shivered at that thought. It would be too hard to find someone who could not be seen.

Ivy, however, didn’t seem to notice Jimmy’s dismissal of my presence. Or if she did, she didn’t care. He sat behind the wheel again, and Ivy scooted up to sit with her arms crossed on the back of the front seat. I could see their exchanges in the rearview mirror.

“So, Jimmy...which way are we headed? Uptown, downtown? Where is this Empire House?”

“Where do you want it to be?” he asked.

“I don’t care if it’s smack in the middle of the East River. I’ve been waiting for this moment for my entire life,” said Ivy.

The truth that I felt in her statement hurt me. I always knew she wanted more from life...but could she have been that unhappy in Forest Grove? And for how long?

She leaned back her head and winked at me. And before I could stop myself, I reached out and tugged hard at the fine edges of her bob that just grazed her exposed back. It pulled her neck in an unnatural direction and she snapped her head away from me yelling “Ow!”

“You all right?” asked Jimmy, even though he was glaring at me in that infernal rearview mirror.

His blue eyes met mine, only I decided to give him my best glare, and it made him turn away.

“Yes, I’m fine,” answered Ivy. “My hair got caught on my sister’s broach. Who even wears high necks anymore?” They were laughing at me, but I knew Ivy was hurt because she kept rubbing the back of her neck. Good, I thought. My shoulders won’t be the same after that trip through the station with our trunks....

“So, you never answered me. Where is this place? Uptown, downtown?” she asked.

“The best part of town. Only the best for you, uh...two. It’s in The Village, right off MacDougal.”

That did it. I put my head into my white-gloved hands, already gray with the filth of the city, and I cried.