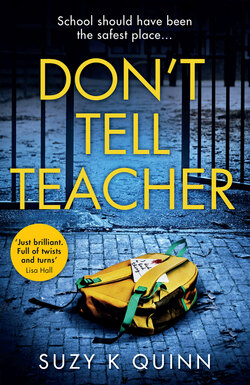

Читать книгу Don’t Tell Teacher - Suzy K. Quinn - Страница 22

ОглавлениеLizzie

We’re early for school today. I’m so determined to be a terrific, organised single parent that I’ve excelled myself.

Tom’s only been here a few weeks. We’re still the new family. Still need to prove ourselves.

Mr Cockrun stands outside the gates when we arrive, scrubbing at some graffiti on the school sign. His rubbery cheeks are red with the effort, hand moving frantically.

I make out some faded spray-paint letters written after Mr Cockrun’s name: CH and then what looks like a faded E and A and another letter so faint as to be nothing but paint speckles.

As Mr Cockrun scrubs the sign clean he notices three approaching schoolgirls. ‘Blazers on properly, please, girls,’ he says. ‘And let’s get the ties nice and straight. If you’re neat and tidy the school is neat and tidy.’

He sounds friendly enough, but the effect on the girls is profound. They hurriedly pluck and pull at their clothing, eyes swishing nervously to the headmaster.

Mr Cockrun nods encouragingly. ‘Let everyone know how proud we are to be Steelfield pupils.’ Then he heads into the school.

I smile at one of the girls. She has red hair, frightened blue eyes and gaps in her teeth. I think she must be ten or eleven.

‘He likes you to look presentable,’ I say.

The girl gives a funny laugh, glancing after the headmaster. ‘We like to look smart,’ she says. ‘It’s important for the school.’

‘Don’t you like to be a bit casual sometimes? You’re still only children.’

The girl looks deeply uncomfortable. ‘No. Mr Cockrun wants everything at school to be perfect.’ She glances at her friends, who nod in agreement.

‘But no school is perfect,’ I say in surprise. ‘Even if it looks perfect. Surely there must be things you’d like to improve.’

The girl gives a tight shake of her head. ‘It’s a wonderful place, and we’re lucky to be here. Semper Fortis. Always strong.’

The girl and her friends scurry off into the playground. I watch them, feeling uneasy.

‘Mum,’ says Tom. ‘I don’t want to go today.’

I push aside my anxiety. ‘I know, love. But you’ll be fine.’ I kneel down, pulling him into a hug. ‘You’re amazing. The best little human being I ever met. I know it’s tough starting a new place, but give it a chance, okay?’ Then I whisper, ‘I know the headmaster is a bit … funny.’

Tom nods. Then he strokes the railings. ‘Silver and grey and blue and black.’

Colours again.

Two other mums appear. They’re dressed in clean jeans, coats and silk scarfs, figures snapped back in place after children.

One of them says, ‘What school doesn’t have bullying? That’s what I told the headmaster. Just because everyone else is too scared to tell doesn’t mean it’s not happening.’

‘And what did he say?’ the other mother asks.

‘Told me flat out there was nothing going on. That he keeps the Neilson boys in line. “Everything is under control,” he said.’

The second mother leans in closer. ‘Noah told me social services are involved with them.’

I stiffen at the mention of social services.

‘Theo said the older boy was slurring his words in the dinner queue …’

The first mother notices me then. She turns her whole body to block me out, and I see sparrow-like shoulder bones poking through her thin coat.

I feel left out.

I am left out.

For a moment, I question the orange scarf I’ve chosen to wear – the one I’ve been knitting in the evenings, listening to music (it feels good to listen to my music, not Olly’s) while Tom is tucked up in bed upstairs. It is a little bright. Maybe even show-offy. Perhaps I should know better than to try to stand out, but I’m ready for change. Something has to change.

I can’t carry on being the invisible woman.

Tom needs a strong mother.

Behind me, a woman says, ‘Scuse me. Are you … Tom’s mum?’

The words are an elastic band, stretched to the point of limpness.

I turn to see a skinny woman, thin blonde hair almost see-through. She’s attempted a smart outfit – a blouse tucked into tight navy jeans – but it doesn’t suit her grey, tired skin or dreamy, slow-moving eyes.

There’s a large pram by her hip with a baby girl inside. I know the baby is a girl because everything is pink – snowsuit, blanket and bow.

‘Hi,’ I say. ‘Sorry, I don’t think we’ve met.’

The woman blinks slowly and says, ‘I’m … Pauly’s mum. Leanne.’ She pauses, looking momentarily confused, then regains her concentration. ‘Pauly said about Tom. They’re … friends?’

‘Oh. Right.’ My hand finds Tom’s shoulder. ‘You’re Pauly’s mum. They’re in the same class, but … I didn’t know they were friends.’

‘You’re … separated like me, aren’t you?’ says Leanne, meeting my eye. ‘That’s what Pauly … says.’

‘Yes.’ I wonder what else the kids at school know about us already.

‘My boys’ dad … left,’ says Leanne. She sways a little and adds, ‘Good riddance. Did yours leave too?’

‘Actually, I left Tom’s dad,’ I say. ‘I tried for a long time to make it work. But you can’t change people unless they want to change.’ This comment is for the two mums standing nearby. I feel them watching me and don’t want to be judged for my failed marriage. It’s Olly’s shame, not mine.

‘We need to look after … each other,’ says Leanne with a languid blink. ‘Especially at this place. It’s not right, is it?’ Her eyes are on mine now and her words become more solid. ‘Lloyd is scared and he’s never scared. And Joey’s been having panic attacks. How’s Tom doing?’

I bite my lip. ‘Not so well, actually.’

‘Listen – don’t you become one of them. “As long as we get our good grades let’s pretend it’s all okay.” They hide a lot at this place. Sweep it under the carpet to make the school look good. I mean, Lloyd is full of shit but I know when he’s lying.’

There’s an awkward silence and then Leanne says, ‘Can Tom come round … this Saturday?’

Tom looks up, eyes frightened.

I can feel lots of parents watching me now. ‘I’m not sure,’ I say. ‘I never quite know what timings are going to be like at weekends.’

‘Oh.’ Leanne’s eyes register confusion, then annoyance, and her head bobs around again.

‘Weekends are busy for us right now. We’ve just moved house.’

‘What about your … ex, can he … you know … help out?’

‘No,’ I say, hearing a hardness to my voice.

‘Adam can pick Tom up, if you like. That’s my partner.’

‘We might be away this weekend. We have to see my mother.’

Tom looks up then. ‘You said it would be just us this weekend.’

I feel myself blushing, caught out. But the last thing I need is Tom involved with a troubled family, and by all accounts the Neilsons are very troubled.

In a bid to ease the irritation in Leanne’s eyes, I hold out my hand and say, ‘I never told you my name. It’s … Lizzie.’

I’ve always preferred Lizzie to Elizabeth. It’s friendlier. And in this historical town outside London, maybe I can make friends.

At Tom’s last school, there was a cliquey vibe. Or maybe there wasn’t. Maybe I was just hard to know – the downtrodden wife, hiding in the shadows.

‘Good to meet you,’ says Leanne. ‘Hopefully we can … you know … help each other out.’ She wobbles her head towards the gossipy mothers. ‘Some people here … they couldn’t care less.’

I smile uncertainly. Then I kneel down and say, ‘Are you ready steady for school, Tommo? Take it easy today.’ I kiss him on the head. ‘Okay. Off you go.’

‘Bye, Mum. Take care today, okay?’

‘Okay, love.’

I watch Tom cross the playground. I’m still watching long after he’s disappeared into the classroom.

Eventually, the headmaster comes to padlock the gates.

As I turn to go, I nearly trip over my feet.

Oh God.

A green van cruises past in the distance.

It’s … it’s …

No, too small. Olly’s camper has a pop-top. That was just a trader’s van.

Olly couldn’t have found us. There’s no way he could have found us.

You’re being paranoid. Jumping at shadows …