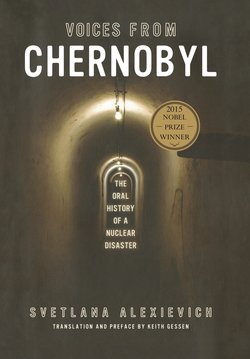

Читать книгу Voices from Chernobyl - Светлана Алексиевич - Страница 11

MONOLOGUE ABOUT A WHOLE LIFE WRITTEN DOWN ON DOORS

ОглавлениеI want to bear witness . . .

It happened ten years ago, and it happens to me again every day.

We lived in the town of Pripyat. In that town.

I’m not a writer. I won’t be able to describe it. My mind is not capable of understanding it. And neither is my university degree. There you are: a normal person. A little person. You’re just like everyone else—you go to work, you return from work. You get an average salary. Once a year you go on vacation. You’re a normal person! And then one day you’re suddenly turned into a Chernobyl person. Into an animal, something that everyone’s interested in, and that no one knows anything about. You want to be like everyone else, and now you can’t. People look at you differently. They ask you: was it scary? How did the station burn? What did you see? And, you know, can you have children? Did your wife leave you? At first we were all turned into animals. The very word “Chernobyl” is like a signal. Everyone turns their head to look at you. He’s from there!

That’s how it was in the beginning. We didn’t just lose a town, we lost our whole lives. We left on the third day. The reactor was on fire. I remember one of my friends saying, “It smells of reactor.” It was an indescribable smell. But the papers were already writing about that. They turned Chernobyl into a house of horrors, although actually they just turned it into a cartoon. I’m only going to tell about what’s really mine. My own truth.

It was like this: They announced over the radio that you couldn’t take your cats. So we put her in the suitcase. But she didn’t want to go, she climbed out. Scratched everyone. You can’t take your belongings! All right, I won’t take all my belongings, I’ll take just one belonging. Just one! I need to take my door off the apartment and take it with me. I can’t leave the door. I’ll cover the entrance with some boards. Our door—it’s our talisman, it’s a family relic. My father lay on this door. I don’t know whose tradition this is, it’s not like that everywhere, but my mother told me that the deceased must be placed to lie on the door of his home. He lies there until they bring the coffin. I sat by my father all night, he lay on this door. The house was open. All night. And this door has little etch-marks on it. That’s me growing up. It’s marked there: first grade, second grade. Seventh. Before the army. And next to that: how my son grew. And my daughter. My whole life is written down on this door. How am I supposed to leave it?

I asked my neighbor, he had a car: “Help me.” He gestured toward his head, like, You’re not quite right, are you? But I took it with me, that door. At night. On a motorcycle. Through the woods. It was two years later, when our apartment had already been looted and emptied. The police were chasing me. “We’ll shoot! We’ll shoot!” They thought I was a thief. That’s how I stole the door from my own home.

I took my daughter and my wife to the hospital. They had black spots all over their bodies. These spots would appear, then disappear. About the size of a five-kopek coin. But nothing hurt. They did some tests on them. I asked for the results. “It’s not for you,” they said. I said, “Then for who?”

Back then everyone was saying: “We’re going to die, we’re going to die. By the year 2000, there won’t be any Belarussians left.” My daughter was six years old. I’m putting her to bed, and she whispers in my ear: “Daddy, I want to live, I’m still little.” And I had thought she didn’t understand anything.

Can you picture seven little girls shaved bald in one room? There were seven of them in the hospital room . . . But enough! That’s it! When I talk about it, I have this feeling, my heart tells me—you’re betraying them. Because I need to describe it like I’m a stranger. My wife came home from the hospital. She couldn’t take it. “It’d be better for her to die than to suffer like this. Or for me to die, so that I don’t have to watch anymore.” No, enough! That’s it! I’m not in any condition. No.

We put her on the door . . . on the door that my father lay on. Until they brought a little coffin. It was small, like the box for a large doll.

I want to bear witness: my daughter died from Chernobyl. And they want us to forget about it.

Nikolai Fomich Kalugin, father