Читать книгу The Spy Who Changed History - Svetlana Lokhova - Страница 10

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

On the hot summer’s day of Sunday, 3 August 1947, a large crowd of Muscovites gathered at Tushino airfield for Aviation Day.1 From early morning they had made their way in their thousands to secure a grassy bank as a vantage point from which to watch the aerobatics and parachute jumps. They waited expectantly to cheer and applaud the heroic pilots, set to perform dizzying barrel rolls and stomach-turning loops.

The stars of the show were a new generation of military aircraft. The message that Soviet leader Joseph Stalin sent to his people and the watching world that day was clear: the Cold War had begun in earnest and his air force was equipped to respond to any threat. In the words of the rousing ‘March of the Soviet Aviators’,2 which was constantly played:

Our keen sight is piercing every atom,

Our every nerve in determination dressed

And trust us, to all enemy ultimatums

Our Air Fleet will give a quick response.fn1

On the VIP balcony, to the left of the grey-haired Stalin in his generalissimo’s uniform, stood a galaxy of Soviet aircraft designers – Alexander Yakovlev, Semyon Lavochkin, Sergey Ilyushin, Pavel Sukhoy, Artem Mikoyan, Mikhail Gurevich,fn2 and the greatest of them all, Andrey Tupolev – who had given their names to a series of iconic military planes. As befitted a day dedicated to celebrating the country’s air force, each man was resplendent in uniforms decorated by rows of gleaming medals.

Standing alongside the diminutive aircraft designer Tupolev was the far taller figure of Colonel Stanislav Shumovsky, a graduate of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). The affable, bespectacled Shumovsky was Tupolev’s friend and long-term collaborator; perhaps more significantly, he was also the most successful aviation spy in history. His latest intelligence coup, which he was still celebrating, had been to bring all of defeated Nazi Germany’s advanced jet and rocket technology back to the Soviet Union.3 But he had enjoyed his most significant successes in the USA, where he had operated with impunity since his arrival at college in 1931.

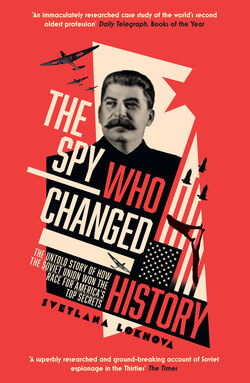

Colonel Shumovsky in air force uniform

Shumovsky pointed out to the stocky Tupolev the faces of the foreign military attachés, who were standing in a separate enclosure. The observers expected to see a parade of prototype jet fighters scream across the sky. The Russians’ plan was to enjoy watching the faces of the American military observers behind their gleaming sunglasses.4 Little did the foreigners know that Tupolev had one major surprise up his sleeve. For the last two years, at the behest of Stalin, he had worked day and night on the Leader’s pet secret project. Uncle Joe, with his flair for combining politics with a flamboyant brand of showmanship, wanted to send a clear message that would have military men in Washington, London, Paris and beyond choking on their tea, and reaching in panic for something far stronger. Thanks to Tupolev’s unceasing, bone-shattering effort, that message was about to be delivered.

After the national anthem and a massive artillery salute, the crowd stood to watch the planes, shielding their eyes with their hands or using binoculars. From the distance, they could hear a faint hum that grew ever louder. Three dots emerged from the patchy clouds, becoming recognisable as giant planes. These were something new from Tupolev, his gift for the Red air force: a four-engined strategic bomber, the Tu-4. Despite the bright red stars on the planes’ tails, the foreign military attachés thought at first this was a simple publicity stunt. Surely the three Tu-4s were just recycled US B-29 Superfortresses? In 1945, three B-29s had made emergency landings in the Soviet Far East while conducting bombing missions against imperial Japan. Perhaps the Soviets, who the military attachés assembled here knew were incapable of producing a high-altitude strategic bomber, had just patched up some American planes with a slick paint job?

Then another dot appeared. It was the Tu-70, a Tupolev-designed passenger version of the Tu-4, and its presence demonstrated that the Soviets were now somehow able to mass-produce their own strategic bomber fleet. Tupolev and Shumovsky glanced over at the American observers, who now looked aghast, deafened by the roar of the colossal aircraft flying above. For them, and indeed for every other Westerner present, it was manifestly clear that the global balance of power had shifted irrevocably to the Reds. Every inch of their territory – the capital cities and industrial heartlands which had long been considered safe from Soviet counter-attack – was now within reach of its modern heavy bomber fleet. This was a crisis. Now all the Soviets needed was the atomic bomb.

• • •

Two years later, on 29 August 1949, at Semipalatinsk in the Kazakh Soviet Republic, Russian scientists detonated ‘First Lightning’,fn3 their atomic bomb. The FBI started a massive, frantic investigation to find how out the ‘backward’ Soviet Union could possibly have accomplished this scientific feat.5

One line of enquiry led the Bureau to search for a shadowy figure they codenamed FRED, a Soviet espionage controller with links to the heart of the atomic programme. For a while, the FBI suspected that FRED was Stanislav Shumovsky.6 Based on information from an informant named Harry Gold, they made the correct assumption that the linchpin in the atomic plot was an alumnus of one of the United States’ finest universities, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. But FRED was not Shumovsky. Stanislav had left the United States long before his aviation espionage exploits were exposed to the FBI. Despite turning over every stone, the Bureau never understood that Shumovsky was just one of many top Soviet spies, all alumni of MIT, and part of an operation that had been up and running for nearly two decades. This is Shumovsky’s story, which the FBI, with all their resources, failed to uncover.

• • •

The first leaders of the Soviet Union Vladimir Lenin and his successor Stalin had always felt threatened by the stronger and technologically superior forces that surrounded their new state. For its security, the Soviet government knew it needed to close the technology gap with those powers it considered potentially hostile, which was virtually everyone. Luckily for the Soviet Union, the nations they perceived as enemies had a flaw. Western countries never understood the value to the USSR of the knowledge and technology they were prepared to trade, teach or simply give away. In particular, Stalin took the decision as early as 1928 to rely on American manufacturers as the Soviet Union’s main supplier of aviation technology.7

On Stalin’s orders, seventy-five Soviet students, including Shumovsky (NKVD codename BLÉRIOT)8 slipped almost unnoticed into the United States during the hot summer of 1931.9 They did not tell the Americans welcoming them to their country that several of the students were also intelligence officers. Stanislav Shumovsky, the first super-spy, was in the vanguard of a mission that by its conclusion had achieved the systematic theft of a large quantity of the US’s scientific and technological secrets – including its most prized of all, the Manhattan Project. But until now, the audacity of the scheme has not been understood or appreciated by the American public, the universities or even the FBI. The mission was distinguished by its daring – Shumovsky would openly film inside America’s most secret sites while wearing his full Red Army uniform;10 its scale – the volume of secrets plundered dwarfs the impact of Cambridge University’s ‘Magnificent Five’ traitors;fn4 and its success – with the fruits of the operation, Stalin was able to bridge the technological gap between the USSR and the USA, equip his air force with a strategic bomber capable of reaching Chicago or Los Angeles, and arm his country with its own nuclear weapons.

‘Stan’,11 as Shumovsky styled himself during his years in the United States, never shot a man in cold blood, never jumped from a burning building (although he was not immune to moments of James Bond-like indiscretion with women).12 Instead, the charismatic, charming and fearsomely clever Soviet intelligence officer cultivated an extrovert image that helped him obscure the cloak-and-dagger work he was conducting. The scheme was simplicity itself. While on campus, Stan’s role was to spot American scientists working in areas of interest to the Soviet Union, approach them on a personal level for cooperation, and subsequently collect information from them. Shumovsky would eventually acquire US secrets on everything from strategic bombers to night fighters, radar guidance to jet engines.13 Each acquisition saved decades’ worth of research and millions of dollars of investment – he secured them for his country at almost no cost.

During his mission, Shumovsky would build a network of contacts and agents in factories and research institutes across the USA. Undiscovered for fifteen years,fn5 he masterminded the systematic acquisition of every aviation secret US industry had to offer. Uniquely, he worked hand in hand with top aircraft designers and test pilots. Designer Andrey Tupolev, one of the world’s greatest experts in ‘reverse-engineering’ (the dismantling and duplication of technology), would present Shumovsky with a ‘shopping list’ of information he needed to solve specific technical issues. What sets Shumovsky’s career apart from those of other intelligence operatives is that he went further than merely gathering information. As talented a scientist as he was a spy, on his return to Russia he established a research institute to analyse and exploit the secrets his network gathered in America and elsewhere.14

• • •

If the trail-blazer Shumovsky had not discovered the usefulness of an MIT education, there would have been no Ethel and Julius Rosenberg, no Klaus Fuchs;fn6 the world we know today would be a very different place. To an extent that has never been acknowledged before, the Soviet Union’s survival during the Second World War was underpinned by the technological and manufacturing secrets, plundered from US universities and factories, that enabled the development and mass manufacture of the aircraft and tanks needed to defeat the Third Reich.

Yet Shumovsky is virtually unknown outside Russian intelligence circles. His service records remain classified. Paradoxically, it is his very obscurity that demonstrates most comprehensively his success: we inevitably know most about the spies who were caught or turned traitor. In 2002, on the centenary of his birth, Shumovsky’s biography was published in Russia by MFTI (the Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology), the university that he helped found in 1946. It celebrated his life and achievements as a scientist and educator.15 But there was a thorny problem to skate around: how to explain in an article that the founder of this prestigious place of learning was one of Russia’s greatest spies. The Institute admitted they had few biographical details of Shumovsky’s earlier career to rely on as he had worked there later in his life. Yet the Journal of Applied Mathematics and Technical Physics was able to publish a very warm but anonymously authored biographical sketch of him. Out of respect, and from a desire for completeness, the Institute turned to an unusual source for more information. As the Journal stated euphemistically, ‘for reasons which, on the basis of the text, we can only guess at, the authors have concealed their names under the collective pseudonym “Colleagues and numerous scientific school pupils of S. A. Shumovsky”.’16 The contributors were in fact his friends and colleagues from the intelligence service, who had access to Shumovsky’s still-classified personnel file. To remove all doubt as to their identity, the anonymous contributors added a footnote to the article that says: ‘It is no coincidence that the portrait of Stanislav Antonovich Shumovsky was placed in the “Hall of Fame” Memorial Museum of the SVR [Foreign Intelligence Service] at Yasenevo.’17

Only the employees of the Russian secret service are allowed inside the Hall of Fame. This is as close as Shumovsky has ever come to an official recognition by Moscow of his achievements as a spy.fn7

Stanislav Shumovsky is known rightly as one of the fathers of Russian aviation. This is the first full account of the unusual and surprising methods that he used to achieve his personal dreams and the goals of the Soviet Union.