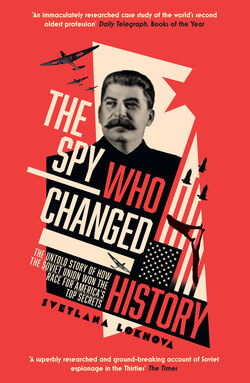

Читать книгу The Spy Who Changed History - Svetlana Lokhova - Страница 9

PREFACE

ОглавлениеIn 1931, Joseph Stalin announced, ‘We are fifty or a hundred years behind the advanced countries. We must catch up in ten years. Either we do it, or they will crush us’.1 These words began a race to close the yawning technology gap between the Soviet Union and the leading capitalist countries. The prize at stake was nothing less than the survival of the USSR. Believing that fleets of enemy bombers spraying poison gas would soon appear in the undefended skies over Russia’s cities, and amid predictions that millions would die from inhaling the deadly toxins, Stalin sent two intelligence officers – an aviation expert and a chemical weapons specialist – on a mission to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. He ordered them to gather the secrets of this centre of aeronautics and chemical weapon research and bring them back to the Soviet Union, along with the means to defend his population against the new terror weapons of modern warfare.

The results of this mission would change the tide of history and lead the KGB to acknowledge that after this first operation ‘the West was a constant and irreplaceable source of acquiring new technologies’ for the USSR.2 After 1931, the Soviets would use scientific and technological intelligence, particularly in the field of aviation, to protect itself against its enemies, culminating in the defeat of Nazi Germany and, thanks to later espionage, helping tilt the global balance of power into an uneasy equilibrium. While both sides possessed weapons of equally massive destructive power, the Cold War did not become a hot war.

Ironically, America was the source of both sides’ nuclear armouries. US agencies later termed the haemorrhage of sophisticated technology to the USSR as ‘piracy’ and tried unsuccessfully to staunch the flow of secrets. In the Soviet Union, the savings resulting from this technical espionage would eventually total hundreds of millions of dollars and be included in official state defence and economic planning.

The experts in the 1930s were half right in their predictions about the future of warfare. By 1945 a nation’s power was determined by the strength of its strategic bombing capability. But the invulnerable high-altitude aircraft were not armed with poison gas. They carried a weapon of far greater destructive power: the atomic bomb. Undreamed of in 1931, this terrifying new device would prove devastatingly more potent a killer than poison gas. In 1945 a single bomb dropped from one plane killed over a hundred thousand people, and one country held a monopoly on this power: the United States.

Yet within four years the Soviets had built their own bomb, joining the US as one of the world’s two superpowers. This pre-eminence would have been unimaginable a quarter of a century previously, when Stalin and Felix Dzerzhinsky sat down to plan the reconstruction of a fragile, illiterate nation reeling from war and successive revolutions. It would be achieved through the sacrifice of millions of lives, lost during the terrible famines that attended collectivisation and on the blood-soaked battlefields of the Eastern Front.

In 1931 a small number of Soviet secret agents infiltrated America to live their lives in the shadows. This is the story of how that long mission first began and how the prestigious Massachusetts Institute of Technology became the greatest, if unwitting, finishing school for Soviet spies – the alma mater of intelligence officers more talented and remarkable than the Cambridge Five traitors Philby, Burgess, Maclean et al. Without the fruits of the spies’ work – the astounding number of technological and scientific secrets they smuggled out – it is hard to believe that the USSR would have prevailed against Nazi Germany or taken its place at the world’s top table.

The stream of intelligence helped prepare the Soviet Union’s armed forces and ready its industrial base for the trials of the Second World War and the Cold War. Across the battlefields of the Eastern Front and in its factories far behind the front lines, the USSR was able to grind Hitler’s previously invincible legions into dust. Defying all expectations, the ‘backward’ Soviet Union mass-produced more planes, tanks and guns than the invading Germans. The secret to crushing the Nazis was stolen American know-how.

By 1942, Stalin was looking beyond the defeat of Hitler and planning for the future defence of the Soviet Union. He sought to overtake his erstwhile Western allies on their home ground, technology. Spreading his net across both sides of the Atlantic in the first coordinated intercontinental espionage gathering operation in history, Stalin’s spies would break the US’s monopoly on the atomic bomb and the high-altitude bomber. These two astonishing technical achievements were completed in four years, less than half the time expected by the Americans.

The US’s global supremacy stemmed from its leadership in science and innovation. Its education system was the brain factory, at the centre of which lay its technical universities. Its economic success was founded on unrivalled techniques of quality mass production, the speed at which it transferred innovation from research centres to factory floors and on mass consumerism. In the 1940s, America’s factories outproduced the world both in terms of quality and quantity. Yet US defence policy relied on the technological sophistication and superiority of the weapons in its armoury, not the number of boots the army could deploy on the ground. In the late 1930s that superior weapon was believed to be the unerringly accurate Norden bomb sight. By the mid 1940s it would be the A-bomb.

The start of the Soviets’ long science and technology (S&T) mission to the US has remained unknown for over eighty years owing to the desire of Russian and US security services to keep their secrets. My sources include previously undiscovered Soviet-era documents that tell the story of the greatest triumph of Stalin’s secret services. As well as how they did it, this book reveals that Soviet intelligence began penetrating the United States ‘to catch up and overtake America’ not to undermine its system of government. The Soviets sought to learn from scientists and entrepreneurs how to industrialise the American way. To surpass the US, they needed to ‘combine American business quality with German attention to detail all on a Russian scale’.3

Over the next five decades the Soviet S&T mission would evolve in its goals, intensity, scale and success, but the main task would be the US, ‘the most advanced country in S&T’,4 and the initial scientist-spies of the first operation would form the model. The mission’s high points were the penetration of the Manhattan Project and the building of the Tu-4 bomber. The first spies would be followed in the 1980s by trained ‘agents [who] were: Doctors of Science, qualified engineers specialising in atomic energy, radio electronics, aviation, chemistry, radars [focusing on] “brain centres”: scientific research institutes, universities, scientific societies’.5 These were the same targets that had been identified by the very first spy, Stanislav Shumovsky, in 1931. The skills that came naturally to him and those he learned on the job would form the basis of an entire KGB programme to train its brightest scientists for missions in the US.

This is the life story of the remarkable Stanislav Shumovsky, a man who changed history. As a young man, he served as a soldier. Against the odds he helped fight off the world’s great powers who sought to strangle Communism in the cradle. When unfit to fight, he used science and technology to transform the Soviet Union from a land with a few imported aircraft to an aviation superpower and an unlikely victor in the Second World War.

Shumovsky was probably the most successful and audacious aviation spy in Soviet history. Appropriately codenamed BLÉRIOT after the legendary French aviator, he provided the USSR with the means to build a modern strategic bomber, which was commissioned to carry the atomic bomb. Among his other notable successes while operating in America during the 1930s, Shumovsky escorted one of the world’s greatest aircraft designers, Andrey Tupolev, around dozens of key US aviation plants, research centres and universities. Along the way Shumovsky recruited as agents a generation of Americans working in the aviation industry (some from his own class at MIT) and filmed inside top-secret US defence plants. A master of public relations, he gave newspaper interviews and posed for photographs, hiding his activities in plain sight for years.

His model for the Soviet scientist-spy formed the key innovation in S&T espionage. Shumovsky would always consider himself an engineer capable of discussing aviation as an equal with the world’s leading experts of the time. He persuaded the NKVD to finance the education of several American recruits by paying their fees at a top university. This is the first evidence of Soviet intelligence investing in young individuals who would prove useful sources in later life. Shumovsky also vouched for and mentored four NKVD officers who enrolled at MIT to learn the skills necessary to continue acquiring technological secrets. The training enabled his protégés to secure the greatest prize of all, the atomic bomb. By 1944, the best Soviet assets of Operation ENORMOZ (their penetration of the Manhattan Project) on both sides of the Atlantic had all been recruited or were run by Shumovsky’s MIT alumni. Of the eighteen Soviet intelligence officers who worked on obtaining the secrets of the atomic bomb, the most senior were graduates of US universities.

Today, Shumovsky’s photograph deservedly hangs in the SVR (Russian Foreign Intelligence Service) Hall of Fame. In Washington and Moscow, the details of his career are still officially classified. Another photograph, taken in 1982 (see here), shows Professor Shumovsky in old age at home. Behind him, on a shelf in a glass cabinet filled with books, is a second photo, evidently a precious memento. It is the picture of a younger Stanislav in his MIT graduation gown, taken in the summer of 1934 on the lawns outside the Institute’s Building 10. The older, relaxed Professor Shumovsky can for the first time perhaps afford a broad smile in a photograph. He stares proudly at the camera, no doubt recalling how he achieved what Stalin had ordered of him all those years before: to provide the crucial information needed for his country’s survival.

To catch up and overtake America is no longer a Russian goal. Others now follow the trail trodden by the Soviets in the 1930s. Today, selling American education abroad is big business. Over a million foreign students are currently enrolled at US universities, around 5 per cent of the total. Disproportionately around a third of those take courses in science, computer technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM). A third of foreign students are Chinese who, according to a 2017 report in the New York Times, contribute an estimated $11.4 billion to the US economy. The advantage to America is that foreign students generally pay full price for their education, subsidising domestic students. Graduates from STEM fields are projected to play a key role in future US economic growth. There is a concern that with so many places taken up by foreign students there may not be enough domestic STEM graduates to meet future job demand. Another is that Chinese and Indian graduates will use their new skills to erode America’s treasured technological superiority. On 14 February 2018, Christopher Wray, head of the FBI, told Congress that ‘Chinese intelligence operatives are littered across US universities, possibly to obtain information in fields like technology. Schools have little understanding of this major predicament.’ Wray warned ‘the level of naivety on the part of the academic sector about this creates its own issues … They’re exploiting the very open research and development environment that we have, which we all revere. But they’re taking advantage of it.’ America remains trapped in a dilemma of fear and greed.

Books that focus on the history of Soviet espionage in the United States and its English-speaking allies often share a troubling Anglo-centric tradition characterised by a reluctance to embrace new non-English sources, in particular those that challenge established narratives. A dearth of Russian-speaking historians is only partly to blame for this continuing problem. The study of Soviet intelligence has been shaped predominantly by the reliance on a few Western primary sources or accounts by journalists and Soviet defectors. Little regard has been given to the inherent bias in this material. For example, the first-hand accounts from former Soviet collaborators-turned-informers such as Harry Gold, Elizabeth Bentley and Boris Morros were unreliable, self-serving and hence problematic. The National Security Agency’s Venona Project that decoded intercepts of Soviet telegrams was considered unreliable as a sole source of identification as long ago as May 1950. The FBI itself recognised how hard it is to identify agents categorically. Even when Soviet sources became widely available after the collapse of the USSR the new material was used only to support established narratives, and documents that did not fit have been largely ignored.

How I found the new material is a story in itself. From the first clue in a declassified NKVD interrogation protocol of 1935, I followed a trail of evidence. That document suggested that in 1931 Soviet Military Intelligence was sending agents on espionage missions to MIT. By verifying this nugget of information through university records and public documents, I was able to uncover the whole story. This book first and foremost lets the new documents speak, and approaches the subject from the perspective of Soviet intelligence officers. This is not the traditional witch hunt to find long-dead traitors who betrayed their country for ideology or money in the 1930s or 1940s. On the contrary, this book looks at a few individuals whose lives were dedicated to the belief that they were making society better. History may have shown their vision of the world to be idealistic but nonetheless they strove hard to ensure that the Soviet Union and its hundreds of millions of people were at least somewhat prepared to fight off the scourge of the Nazis. For that, we should be grateful.

Among the many surprises and revelations in this book are the identification of a number of new Soviet spies on previously unknown operations. The findings establish that significant penetration of the US started a decade earlier than many previously believed. In addition, the involvement of major US figures in Soviet espionage began far sooner than has been made public before, with for example Earl Browder and Nathan Silvermaster active many years earlier than previously thought.

Women play a strong and full role in these early intelligence operations out in the field. In a profession dominated by men these women are not playing the traditional support roles of honey traps, such as Mata Hari. Ray (Raisa) Bennett and Gertrude Klivans are refreshingly modern young women who from an early age knew their own minds. We are privileged to hear their voices through their own words. Both were no shrinking violets but followed their own independent paths in life. Raisa Bennett had to juggle the responsibilities of being a Soviet Military Intelligence officer on a dangerous mission abroad while also mother to a young child. Gertrude Klivans had plenty of opinions and plenty of men, all the while training the future top spies how to be American.

Of historical significance is the story of Military Intelligence officer Mikhail Cherniavsky. At the time, his assassination plot attracted the close attention of the intelligence services and political elite. Only two pieces of intelligence were ever underlined by the NKVD and one was the revelation from a source in Boston of a growing Trotskyist opposition in Moscow linked to an international revolutionary movement. Cherniavsky was the ringleader of a plot to kill Stalin and replace him with Trotsky. It was Cherniavsky’s bullets that Stalin referred to in his speech to the Graduates of the Red Army Academies delivered in the Kremlin on 4 May 1935:

But these comrades did not always confine themselves to criticism and passive resistance. They threatened to raise a revolt in the Party against the Central Committee. More, they threatened some of us with bullets. Evidently, they reckoned on frightening us and compelling us to turn from the Leninist road.

Finally, through my research for this book I was delighted to lay to rest one ghost. I uncovered the life and intelligence career of Ray Bennett, the first American to serve as a Soviet Military Intelligence officer in the United States. Eighty years ago, Ray vanished from her young daughter’s life. Joy Bennett ran into Ray’s bedroom, as she did every morning, to discover her mother had disappeared. In 2017 I was able to explain to Joy her mother’s career and the reason behind her arrest and eventual disappearance. Joy kindly described my work as ‘sacred’.

During the period of history that this book covers the Russian secret services organisations changed their names many times, and for the sake of simplicity (and despite this being historically inaccurate), I have called them the NKVD or Military Intelligence throughout the book. To avoid confusing the reader further, Russian names are spelled using ‘y’ for ‘i’, so for example ‘Andrey’ not ‘Andrei’, and I have used ‘Y’ at the start of certain names, such as ‘Yershov’ not ‘Ershov’.