Читать книгу Pushkin - T. Binyon J. - Страница 15

7 KISHINEV 1820â23

ОглавлениеCursed town of Kishinev!

My tongue will tire itself in abuse of you.

Some day of course the sinful roofs

Of your dirty houses

Will be struck by heavenly thunder,

And â I will not find a trace of you!

There will fall and perish in flames,

Both Varfolomeyâs motley house

And the filthy Jewish booths:

So, if Moses is to be believed,

Perished unhappy Sodom.

But with that charming little town

I dare not compare Kishinev,

I know the Bible too well,

And am wholly unused to flattery.

Sodom, you know, was distinguished

Not only by civilized sin,

But also by culture, banquets,

Hospitable houses

And by the beauty of its far from strict maidens!

How sad, that by the untimely thunder

Of Jehovahâs wrath it was struck!

From a letter to Wiegel, October 1823

KISHINEV WAS THE CAPITAL OF BESSARABIA, which lies between the rivers Dniester and Prut, the Danube delta and the Black Sea. It had been colonized successively by the Greeks, Romans and Genoese, had been annexed by the principality of Moldavia in 1367, become part of the Ottoman empire in 1513, and had been ceded to Russia in 1812 by the Treaty of Bucharest. When Pushkin arrived on 21 September 1820, he found a bustling, lively, colourful town, very different from the decaying imperial pomp of Ekaterinoslav. At that time it had some twenty thousand inhabitants. The majority were Moldavians, but there were also large Bulgarian and Jewish colonies, numbers of Greeks, Turks, Ukrainians, Germans, and Albanians, and even French and Italian communities; the relatively small Russian population consisted mainly of military personnel and civil servants. The old town, âwith its narrow, crooked streets, dirty bazaars, low shops and small houses with tiled roofs, but also with many gardens planted with Lombardy poplars and white acaciasâ,1 was spread out along the flat and muddy banks of a little river, the Byk. On the hills above was the new town, with the municipal garden, the theatre and the casino, administrative offices, and a number of stone houses in which the governor, the military commander, the metropolitan and other notables lived.

Initially Pushkin put up in a small inn in the old town. At the beginning of October, however, he moved into a house rented by Inzov: a large, stone building in an isolated position near the old town, on a hill above the Byk. Inzov and several officials lived on the upper floors; Pushkin and his servant Nikita inhabited two rooms on the ground floor, through whose barred windows he looked out over an orchard and vineyard to the open country and mountains beyond. The walls were painted blue; one was soon disfigured with blobs of wax: Pushkin, sitting naked on his bed, would practise his marksmanship by â like Sherlock Holmes at 221B Baker Street â picking out initials on the wall with wax bullets from his pistols. Another of Inzovâs officials, Andrey Fadeev, was obliged to share this room on his visits to Kishinev. âThis was extremely inconvenient, for I had come on business, had work to do, got up and went to bed early; but some nights he did not sleep at all, wrote, moved about noisily, declaimed, and recited his verse in a loud voice. In summer he would disrobe completely and perform in the room all his nocturnal evolutions in the full nudity of his natural form.â2 On 14 July and 5 November 1821 earthquakes struck Kishinev. The second, more severe, damaged the house. Inzov and the civil servants moved out immediately, but Pushkin, either through indolence or affection for his quarters â the first independent lodging he had had â stayed put, living there by himself for several months.

The day after his arrival Pushkin presented himself to Inzov, who introduced him to some members of his staff: Major Sergey Malevinsky, the illegitimate son of General Ermolov, then commanding the Russian armies in the Caucasus; and Nikolay Alekseev, who was to become a close friend. Ten years older than Pushkin, he knew many of the latterâs friends in St Petersburg, and, with a taste for literature, âwas the only one among the civil servants in whose person Pushkin could see in Kishinev a likeness to that cultured society of the capital to which he was usedâ.3 That evening Malevinsky took him to the casino in the municipal gardens, which also served as a club for officers, civil servants and local gentry. A rudimentary restaurant was attached to the club, run by Joseph, the former maître dâhôtel of General Bakhmetev, Inzovâs predecessor. It became a regular port of call for Pushkin, who heard from a waitress, Mariola, the Moldavian song on which he based his poem âThe Black Shawlâ.*

The following day Pushkin dined with his old friend and fellow-member of Arzamas, General Mikhail Orlov, recently appointed to the command of the 16th Infantry Division, whose headquarters were in Kishinev. Here he met Orlovâs younger brother, Fedor, a colonel in the Life Guards Uhlans, who had lost a leg at the battle of Bautzen, together with several of Orlovâs officers: Major-General Pushchin, who commanded a brigade in the division; Captain Okhotnikov, Orlovâs aide-de-camp; and Ivan Liprandi, a lieutenant-colonel in the Kamchatka regiment, and one of Orlovâs staff officers. Liprandi was an interesting, somewhat mysterious character, who soon became another of Pushkinâs intimates.

Born in 1790, the son of an Italian émigré and a Russian baroness, he had made a name for himself in military intelligence during the Napoleonic wars. He was promoted lieutenant-colonel at twenty-four, and seemed on the verge of a brilliant career, but after a duel â one of several â which resulted in the death of his opponent, was transferred from the guards to an army regiment and posted to Kishinev. Pushkin, who would describe him as âuniting genuine scholarship with the excellent qualities of a military manâ,4 was immediately attracted to him, pestered him with questions about his duels, and borrowed books from his library. The day after meeting Pushkin, Liprandi dined with Prince George Cantacuzen and his wife Elena, the addressee of Pushkinâs Lycée poem, âTo a Beauty Who Took Snuff.â They asked Liprandi to bring Pushkin round to see them; though protesting that his acquaintance with the poet was very short, the next day he, Fedor Orlov, and Pushkin called on the Cantacuzens, stayed for dinner, and remained drinking until well after midnight.

Pushkin soon had a wide circle of acquaintances and friends among the civilians and officers in the town. Some he had known, or heard of, earlier: a Lycée friend, Konstantin Danzas, now an officer in the engineers, was stationed here, as were the cousins Mikhail and Aleksey Poltoratsky, both cousins of Anna Kern, whose beauty had so impressed Pushkin at the Olenins in St Petersburg. They were attached to a unit of the general staff which was carrying out a military topographical survey of Bessarabia. Another member was Aleksandr Veltman. Later a well-known novelist, at this time he dabbled in poetry, and, cherishing a profound admiration for Pushkinâs work, initially held himself timidly aloof from him, fearing a comparison between their achievements. Chance, however, brought them together; Pushkin learnt of his verse and, calling at Veltmanâs lodgings, asked him to read the work on which he was then engaged: an imitation Moldavian folk-tale in verse, entitled âYanko the Shepherdâ, some episodes of which caused him to laugh uproariously.

Among the local inhabitants he frequently visited the civil governor, Konstantin Katakazi: âHaving yawned my way through mass,/I go to Katakaziâs,/What Greek rubbish!/What Greek bedlam!â he wrote.5 Most evenings a company gathered to play cards at the home of the vice-governor, Matvey Krupensky; here Pushkin could satisfy his addiction to faro. Krupenskyâs large mansion housed not only the provinceâs revenue department, but also, in a columned hall decorated with a frieze emblematic of Russian military achievement, the townâs small theatre. At the beginning of November, a twenty-year-old ensign, Vladimir Gorchakov, who had just arrived in Kishinev and was attached to Orlovâs staff, attended a performance given by a travelling troupe of German actors. âMy attention was particularly caught,â he wrote in his diary, âby the entrance of a young man of small stature, but quite strong and broad-shouldered, with a quick and observant gaze, extraordinarily lively in his movements, often laughing in a surfeit of unconstrained gaiety and then suddenly turning meditative, which awoke oneâs sympathy. His features were irregular and ugly, but the expression of thought was so fascinating that involuntarily one wanted to ask: what is the matter? What grief darkens your soul? The unknownâs clothing consisted of a closely buttoned black frock-coat and wide trousers of the same colour.â6 This was Pushkin; during the interval Alekseev introduced Gorchakov to him, and the two were soon deep in reminiscences of the St Petersburg theatre and of their favourite actresses, Semenova and Kolosova.

Another prominent member of Kishinev society was Egor Varfolomey, a wealthy tax-farmer and member of the supreme council of Bessarabia. He was extremely hospitable: it was very difficult to visit him and not stay to dinner; but for the young officers and civil servants the main attractions of the house were the informal dances in his ballroom and his eighteen-year-old daughter, Pulkheriya. She was a pretty, plump, healthy, empty-headed girl, with few powers of conversation, whose invariable reply to advances, compliments or witticisms was âWho do you think you are! What are you about!â â Veltman, in a flight of fancy, surmised that she might be an automaton.7 Nevertheless, Pushkin, for want of a better object for his affections, fell in love with her during his stay in Kishinev. It was hardly a passionate affair, and did not prevent him from languishing, during the next three years, after many others: Mariya Schreiber, the shy seventeen-year-old daughter of the president of the medical board, for example; or Viktoriya Vakar, a colonelâs wife with whom he often danced; or the playful, dark-complexioned Anika Sandulaki. He sighed from afar after pretty Elena Solovkina, who was married to the commander of the Okhotsk infantry regiment and occasionally visited Kishinev, and made a determined assault on the virtue of Ekaterina Stamo, whose husband Apostol, a counsellor of the Bessarabian civil court, was some thirty years older than her. âPushkin was a great rake, and in addition I, unfortunately, was considered a beauty in my youth,â Ekaterina remarked in her recollections. âI had great difficulty in restraining a young man of his age. I always had the most strict principles, â such was the upbringing we all had been given, â but, you know, Aleksandr Sergeevichâs views on women were somewhat lax, and then one must take into account that our society was strange to him, as a Russian. Thanks to my personal tact [â¦] I managed finally to arrange things with Aleksandr Sergeevich in such a way that he did not repeat the declaration which he had made to me, a married woman.â8 She was one of the seven children of Zamfir Ralli, a rich Moldavian landowner with estates to the west of Kishinev. Pushkin got to know the family very well during his stay in Kishinev: they were his closest friends among the Moldavian nobility, and he was especially intimate with Ivan, Ekaterinaâs brother, a year younger than himself, who shared his literary tastes. Another Kishinev beauty was Mariya Eichfeldt, âwhose pretty little face became famous for its attractiveness from Bessarabia to the Caucasusâ.9 She had a much older husband: Pushkin christened the couple âZémire and Azorâ, after the French opéra comique with that name on the theme of Beauty and the Beast. He flirted with her in society, but refrained from pressing his advances further, as she was Alekseevâs mistress: âMy dear chap, how unjust/Are your jealous dreams,â he wrote.10

At the beginning of November General Raevskyâs two half-brothers, Aleksandr and Vasily Davydov, came to stay with Orlov. âAleksandr Lvovich,â Gorchakov noted, âwas distinguished by the refinement of a marquis, Vasily flaunted a kind of manner peculiar to the common man [â¦] They were both very friendly towards Pushkin, but Aleksandr Lvovichâs friendliness was inclined to condescension, which, it seemed to me, was very much disliked by Pushkin.â11 Orlov was about to visit the Davydov estate at Kamenka â some 160 miles to the south-east of Kiev, not far from the Dnieper â and the brothers also extended an invitation to Pushkin. He accepted with alacrity; Inzov gave his permission; and in the middle of November he left with the Davydovs. Passing through Dubossary, Balta, Olviopol and Novomirgorod, they arrived in Kamenka three days later. General Raevsky and his son Aleksandr were already there, having travelled down from Kiev; Mikhail Orlov and his aide-de-camp Okhotnikov soon followed, bringing with them Ivan Yakushkin, who âwas pleasantly surprised when A.S. Pushkin [â¦] ran out towards me with outstretched armsâ: they had been introduced to one another in St Petersburg by Chaadaev.12

Kamenka was one of the centres of the Decembrist movement in the south; the other, more important, was Tulchin, the headquarters of the Second Army, where Pestel was stationed. The gathering here, ostensibly to celebrate the name-day, on 24 November, of Ekaterina Nikolaevna, the mother of General Raevsky and of the Davydov brothers, was in effect a meeting of a number of the conspirators: Orlov, Okhotnikov, Yakushkin and Vasily Davydov. The party dined luxuriously each evening with Ekaterina Nikolaevna, and then retired to Vasilyâs quarters for political discussions.

Orlov and Okhotnikov left at the beginning of December. Pushkin had intended to accompany them, but was prevented by illness. Aleksandr Davydov made his excuses to Inzov, writing that âhaving caught a severe cold, he is not yet in a condition to undertake the return journey [â¦] but if he feels soon some relief in his illness, will not delay in setting out for Kishinevâ.13 Inzov replied sympathetically, thanking Davydov for allaying his anxiety, since, he wrote, âUp to now I was in fear for Mr Pushkin, lest he, regardless of the harsh frosts there have been with wind and snow, should have set out and somewhere, given the inconvenience of the steppe highways, should have met with an accident [but am] reassured and hope that your excellency will not allow him to undertake the journey until he has recovered his strength.â14 He enclosed with his letter a copy of a demand for the repayment of 2,000 roubles, which Pushkin had borrowed from a money-lender in November 1819 to pay a debt at cards.

A few days later Pushkin wrote to Gnedich: âI am now in the Kiev province, in the village of the Davydovs, charming and intelligent recluses, brothers of General Raevsky. My time slips away between aristocratic dinners and demagogic arguments. Our company, now dispersed, was recently a varied and jolly mixture of original minds, people well-known in our Russia, interesting to an unfamiliar observer. Women are few, there is much champagne, many witty words, many books, a few verses.â15 Though there may have been few women in Kamenka, Pushkin made the best of the situation and enjoyed an affair with Aglaë Davydova, Aleksandr Lvovichâs thirty-three-year-old wife. It was a short-lived liaison. The difference in age and social position between the two led Aglaë to treat him with a patronizing condescension that was as distasteful to Pushkin in his mistress as it had been in her husband. When Liprandi dined with Davydov and his wife in St Petersburg in March 1822 he noted that she âwas not very favourably disposed towards Aleksandr Sergeevich, and it was obviously unwelcome to her, when her husband asked after him with great interestâ, and added: âI had already heard a number of times of the kindness shown to Pushkin at Kamenka, and heard from him enthusiastic praise of the family society there, and Aglaë too had been mentioned. Then I learnt that there had been some kind of quarrel between her and Pushkin, and that the latter had rewarded her with some verses!â16 The affair had indeed broken off acrimoniously, and Pushkin, hurt and insulted, gave vent to his feelings with four extraordinarily spiteful epigrams. One, commenting on her promiscuity, wonders what impelled her to marry Davydov; another, coarse and excessively indecent even by Pushkinâs standards, portrays her as sexually insatiable; the least offensive, and the wittiest, is in French:

To her lover without resistance Aglaë

Had ceded â he, pale and petrified,

Was making a great effort â at last, incapable of more,

Completely breathless, withdrew ⦠with a bow, â

âMonsieurâ, says Aglaë in an arrogant tone,

âSpeak, monsieur: why does my appearance

Intimidate you? Will you tell me the cause?

Is it disgust?â âGood heavens, itâs not that.â

âExcess of love?â âNo, of respect.â17

Pushkin did not leave Kamenka until the end of January 1821, then travelling, in the company of the Davydov brothers, not to Kishinev but to Kiev, where he put up with General Raevsky, and met the âhussar-poetâ Denis Davydov, cousin both of the Davydovs and of General Raevsky, famous for his partisan activities during the French armyâs retreat in 1812 â the model for Denisov in War and Peace. âHussar-poet, youâve sung of bivouacs/Of the licence of devil-may-care carousals/Of the fearful charm of battle/And of the curls of your moustache,â he wrote.18 In the second week of February he and the Davydovs set off for Tulchin, some 180 miles to the west. His St Petersburg acquaintance General Kiselev was now chief of staff of the Second Army here: he was to marry Sofya Potocka later that year. âI had the occasion to see [Pushkin] in Tulchin at Kiselevâs,â wrote Nikolay Basargin, a young ensign in the 31st Jägers. âI was not acquainted with him, but met him two or three times in company. I disliked him as a person. There was something of the bully about him, an element of vanity, and the desire to mock and wound others.â19 After a week in Tulchin Pushkin, still avoiding his official duties, returned to Kamenka with the Davydovs, arriving on or about 18 February.

During his first stay on the estate he had begun a new notebook, copying into it fair versions of his Crimean poems âA Nereidâ and âSparser grows the flying range of cloudsâ, and continuing to work on The Prisoner of the Caucasus. Now, lying on the Davydovsâ billiard table surrounded by scraps of manuscript, so engrossed in composition as to ignore everything about him, he produced the first fair copy of the poem, adding at the end of the text the notation â23 February 1821, Kamenkaâ.20 Despite this achievement, he was often in a bleak mood. âBeneath the storms of harsh fate/My flowering wreath has faded,â he had written the previous day.21 He was isolated from his family and his closest friends, from the literary and social life of the capital; the best years of his poetic and personal life were being wasted in a provincial slough. Melancholy was to recur ever more frequently during his years of exile: âI am told he is fading away from depression, boredom and poverty,â Vyazemsky wrote to Turgenev in 1822.22 Constantly deluding himself with hopes of an end to his exile, or at least of being granted leave to visit St Petersburg â âI shall try to be with you myself for a few days,â he wrote to his brother in January 182223 â he was as constantly brought to face the reality of his situation. When, a year later, he made a formal application to Nesselrode for permission to come to St Petersburg, âwhither,â he wrote, âI am called by the affairs of a family whom I have not seen for three yearsâ,24 he found that Alexander had not forgotten his misdemeanours: Nesselrodeâs report was endorsed by the emperor with a single word: âRefusedâ.25 He could not but compare himself to Ovid: their fates were strangely alike. Because of their verse (and, in Ovidâs case, also for some other, mysterious crime) both had been exiled by an emperor â Ovid by Augustus, the former Octavian, in AD 8 â to the region of the Black Sea. In Ovidâs works written in exile â Tristia and Black Sea Letters â Pushkin found reflections of an experience analogous to his own, and contrasted his emotions as an exile from St Petersburg with those of Ovid as an exile from Rome. âLike you, submitting to an inimical fate,/ I was your equal in destiny, if not in fame,â he wrote in âTo Ovidâ, completed on 26 December 1821.26

Financial worries â âHe hasnât a copeckâ, Vyazemsky noted27 â added to his depression. He had been paid no salary since leaving St Petersburg. In April 1821 Inzov pointed this out to Capo dâIstrias, adding: âsince he receives no allowance from his parent, despite all my assistance he sometimes, however, suffers from a deficiency in decent clothing. In this respect I consider it my most humble duty to ask, my dear sir, that you should instruct the appointment to him of that salary which he received in St Petersburg.â28 As a result he received a yearâs salary â less hospital charges and postal insurance it came to 685 roubles 30 copecks â in July, and was thereafter paid at four-monthly intervals. But this, though welcome, could not resolve his financial problems. On 5 May, in reply to the demand for 2,000 roubles forwarded by Inzov, he wrote, ânot being yet of age and possessing neither movable nor immovable property, I am not capable of paying the above-mentioned promissory note.â29 The âdeficiency in decent clothingâ was noted by others: âHe leads a dissipated life, roams the inns, and is always in shirt-sleeves,â wrote Liprandi.30 His attire in Kishinev tended towards the bizarre: sometimes he dressed as a Turk, sometimes as a Moldavian, sometimes as a Jew, usually topping the ensemble with a fez â costumes which were adopted, not primarily from eccentricity, but because of the absence from his wardrobe of more formal wear. âMy father had the brilliant idea of sending me some clothes,â he wrote to his brother. âTell him that I asked you to remind him of it.â31

He had eventually left Kamenka towards the end of February, and, taking a long way round through Odessa, where he spent two days, arrived in Kishinev early in March.* He found a town much stirred by events which had taken place during his absence. In 1814 three Greek merchants in Odessa, one of the most important Greek communities outside the Ottoman empire, had founded the Philike Hetaireia (Society of Friends), whose aim was the liberation of Greece from Turkish rule. The society was soon actively engaged in conspiracy: intriguing with potential rebels, it persuaded its Greek supporters that the tsar, as the head of the greatest Orthodox state, would be unable to ignore any bid for Greek independence. In 1819â20 the time seemed ripe for an uprising: there were intimations or outbreaks of revolt in Germany, Spain, Piedmont and Naples. The society offered its leadership to Capo dâIstrias; he refused, and it turned in his stead to Alexander Ypsilanti, a Phanariot Greek,â the son of the former hospodar of Moldavia and Wallachia. An officer in the Russian army, Ypsilanti had distinguished himself in the campaigns of 1812 and 1813, losing an arm at the battle of Dresden. He had attended Alexander I, as one of the emperorâs adjutants, at the congress of Vienna, and in 1817 had been promoted major-general and given command of a cavalry brigade. On his election to the leadership of the society he moved to Kishinev.

On the night of 21 February 1821, at Galata â the principal port of Moldavia, on the left bank of the Danube â the small Turkish garrison and a number of Turkish merchants were massacred by Greeks; the following day Alexander Ypsilanti, accompanied by his brothers, George and Nicholas, Prince Cantacuzen, and several other Greek officers in Russian service, crossed the Prut. At IaÅi on the twenty-third, in proclamations addressed to the Greeks and Moldavians, he called on them to rise against the Turks, declaring that his enterprise had the support of a âgreat powerâ. Though Michael Souzzo, the hospodar, threw in his lot with the uprising, it enjoyed no popular support, and Ypsilanti condemned it to failure by his irresolute leadership, condoning, in addition, the massacre at Galata and a subsequent similar incident at IaÅi. A final blow to the revolt was a letter from Alexander I, signed by Capo dâIstrias, which denounced Ypsilantiâs actions as âshameful and criminalâ, upbraided him for misusing the tsarâs name, struck him from the Russian army list, and called upon him to lay down his arms immediately.32 Though Ypsilanti endeavoured to brave matters out, he was abandoned by many of the revolutionary leaders, and, retreating slowly northwards towards the Austrian frontier, underwent a series of humiliating defeats, culminating in that of Dragashan on 7 June, after which he escaped into Austria. Here he was kept in close confinement for over seven years, and, when eventually released at the instance of Nicholas I, died in Vienna in extreme poverty in 1828. A simultaneous revolt in Greece itself, led, among others, by Ypsilantiâs brother Demetrios, proved more successful: in 1833, after the intervention of the Great Powers, it eventually resulted in the establishment of an independent Greece.

Ypsilantiâs insurrection had been in progress for just over a week when Pushkin returned to Kishinev. The boldness of this exploit in the cause of Greek independence could not fail to arouse his enthusiasm. He dashed off a letter to Vasily Davydov, telling him of the progress of the revolt, speculating on Russiaâs policy â âWill we occupy Moldavia and Wallachia in the guise of peace-loving mediators; will we cross the Danube as the allies of the Greeks and the enemies of their enemies?â â and quoting from an insurgentâs letter on events at IaÅi: âHe describes with ardour the ceremony of consecrating the banners and Prince Ypsilantiâs sword â the rapture of the clergy and laity â and the sublime moments of Hope and Freedom.â Ypsilanti, whom Pushkin had met the previous year, is mentioned with admiration: âAlexander Ypsilantiâs first step is splendid and brilliant. He has begun luckily â from now on, whether dead or a victor he belongs to history â 28 years old, one arm missing, a magnanimous goal! â an enviable lot.â33 âWe spoke about A. Ypsilanti,â he records in his diary of an evening at the house of a âcharming Greek ladyâ. âAmong five Greeks I alone spoke like a Greek â they all despair of the success of the Hetaireia enterprise. I am firmly convinced that Greece will triumph, and that 25,000,000* Turks will leave the flowering land of Hellas to the rightful heirs of Homer and Themistocles.â34 Indeed, his enthusiasm was such that it became rumoured that he â as Byron was to do two years later â had joined the revolt. âI have heard from trustworthy people that he has slipped away to the Greeks,â the journalist and historian Pogodin wrote to a friend from Moscow.35 But his participation was only vicarious.

The question of Russiaâs attitude to the insurrection, which Pushkin raises in his letter to Davydov, was one which preoccupied both the government and the Decembrists. Both were not averse to striking a blow against Russiaâs old enemy, Turkey. âIf the 16th division,â Orlov remarked of his command, âwere to be sent to the liberation [of Greece], that would not be at all bad. I have sixteen thousand men under arms, thirty-six cannon, and six Cossack regiments. With that one can have some fun. The regiments are splendid, all Siberian flints. They would blunt the Turkish swords.â36 Alexander, however, did not wish to back revolutionary activity in Greece, while the Decembrists, though supporters of Greek independence, were not eager to have an illiberal tsar gain kudos by posing as a liberator abroad. And, curiously, they had the opportunity of influencing events. At the beginning of April Kiselev was requested by the government to send an officer to Kishinev to report on the insurrection. His choice fell on Pestel, whose report may have been instrumental in persuading the government not to support the revolt: Pushkin certainly believed this to be the case. In November 1833, at a rout at the Austrian ambassadorâs in St Petersburg, he met Michael Souzzo, the former hospodar of Moldavia. âHe reminded me,â Pushkin wrote in his diary, âthat in 1821 I called on him in Kishinev together with Pestel. I told him how Pestel had deceived him, and betrayed the Hetaireia â by representing it to the Emperor Alexander as a branch of Carbonarism. Souzzo could conceal neither his astonishment nor his vexation â the subtlety of a Phanariot had been conquered by the cunning of a Russian officer! This wounded his vanity.â37

Pushkinâs confidence in the success of the revolt soon proved unjustified â at least as far as Moldavia was concerned, where the uprising was quickly suppressed by the Turks. After a final, bloody engagement at Sculeni, on the west bank of the Prut, in June, the few survivors escaped by swimming the river. Gorchakov, who had been sent to observe events from the Russian side, gave Pushkin an account of this incident, which he later made use of in the short story âKirdzhaliâ. Though he remained constant in his support for Greek independence, he was disappointed by this âcrowd of cowardly beggars, thieves and vagabonds who could not even withstand the first fire of the worthless Turkish musketryâ. âAs for the officers, they are worse than the soldiers. We have seen these new Leonidases in the streets of Odessa and Kishinev â we are personally acquainted with a number of them, we can attest to their complete uselessness â they have discovered the art of being boring, even at the moment when their conversation ought to interest every European â no idea of the military art, no concept of honour, no enthusiasm â the French and Russians who are here show them a contempt of which they are only too worthy, they put up with anything, even blows of a cane, with a sangfroid worthy of Themistocles. I am neither a barbarian nor an apostle of the Koran, the cause of Greece interests me keenly, that is just why I become indignant when I see these wretches invested with the sacred office of defenders of liberty.â38

As the failure of the insurrection became apparent, refugees began to flood into Bessarabia: Moldavian nobles, Phanariot Greeks from the Turkish territories and Constantinople, Albanians and others. Their presence certainly made Kishinev a more lively place, and Pushkinâs circle of acquaintances was widened by a number of the new arrivals. Among these was Todoraki Balsch, a Moldavian hatman â military commander â who had fled from IaÅi with his wife Mariya â âa woman in her late twenties, reasonably comely, extremely witty and loquaciousâ39 â and daughter Anika. For some time Mariya was the sole object of Pushkinâs attentions; they held long, uninhibited conversations in French together, and she became convinced that he was in love with her. However, he suddenly transferred his allegiance to another refugee from IaÅi, Ekaterina Albrecht, âtwo years older than Balsch, but more attractive, with unconstrained European manners; she had read much, experienced much, and in civility consigned Balsch to the backgroundâ.40 Ekaterina came from an old Moldavian noble family, the Basotas, and was separated from her third husband, the commander of the Life Guards Uhlans: qualities which attracted Pushkin â he remarked that she was âhistorical and of ardent passionsâ.41 As a result, Mariyaâs feelings turned to virulent dislike, which the following year was to give rise to a notable scandal.

Another refugee was Calypso Polichroni, a Greek girl who had fled from Constantinople with her mother and taken a humble two-room lodging in Kishinev. She went little into society; indeed, would hardly have been welcomed there, for her morals were not above suspicion. âThere was not the slightest strictness about her conversation or her behaviour,â Wiegel noted, adding euphemistically: âif she had lived at the time of Pericles, history, no doubt, would have recorded her name together with those of Phryne and Laïsâ42 â famous courtesans of the past. âExtremely small, with a scarcely noticeable bosom,â Calypso âhad a long, dry face, always rouged in the Turkish manner; a huge nose as it were divided her face from top to bottom; she had thick, long hair and huge fiery eyes made even more voluptuous by the use of kohlâ;43 and âa tender, attractive voice, not only when she spoke, but also when she sang to the guitar terrible, gloomy Turkish songsâ.44 But what excited Pushkinâs imagination âwas the thought that at about fifteen she was supposed to have first known passion in the arms of Lord Byron, who was then travelling in Greeceâ.45 If Vyazemsky came to Kishinev, Pushkin wrote, he would introduce him to âa Greek girl, who has exchanged kisses with Lord Byronâ.46 âYou were born to set on fire/The imagination of poets,â he told her.47 A juxtaposition of Byronâs life with what is known of Calypsoâs shows they can never have met. But in inventing the story, Calypso revealed an acute perception of psychology: in dalliance with her there was an extra titillation to be derived from the feeling that one was following, metaphorically, in Byronâs footsteps. Bulwer-Lytton is supposed to have gained a peculiar satisfaction from an affair with a woman whom Byron had loved, while the Marquis de Boissy, who married Teresa Guiccioli, would, it was reported, introduce her as âMy wife, the Marquise de Boissy, Byronâs former mistressâ.48 Pushkin was not immune to this thrill.*

Meanwhile Inzov had put him to work. Peter Manega, a Rumanian Greek who had studied law in Paris, had produced for Inzov a code of Moldavian law, written in French, and Pushkin was given the task of turning it into Russian. In his spare time he began to study Moldavian, taking lessons from one of Inzovâs servants. He learnt enough to be able to teach Inzovâs parrot to swear in Moldavian. Chuckling heartily, it repeated an indecency to the archbishop of Kishinev and Khotin when the latter was lunching at Inzovâs on Easter Sunday. Inzov did not hold the prank against Pushkin; indeed, when Capo dâIstrias wrote a few weeks later to enquire âwhether [Pushkin] was now obeying the suggestions of a naturally good heart or the impulses of an unbridled and harmful imaginationâ, he replied: âInspired, as are all residents of Parnassus, by a spirit of jealous emulation of certain writers, in his conversations with me he sometimes reveals poetic thoughts. But I am convinced that age and time will render him sensible in this respect and with experience he will come to recognize the unfoundedness of conclusions, inspired by the reading of harmful works and by the conventions accepted by the present age.â49 Had he known what Pushkin was writing he might not have been so generous.

At this period in his life Pushkin was a professed, indeed a militant atheist, modelling himself on the eighteenth-century French rationalists he admired. Whether or not he was the author, while at St Petersburg, of the quatrain âWe will amuse the good citizens/And in the pillory/With the guts of the last priest/Will strangle the last tsarâ,â 50 an adaptation of a famous remark by Diderot, his view of religion emerges clearly from much of his Kishinev work. When Inzov, a pious man, made it clear that he expected his staff to attend church, Pushkin, in a humorous epistle to Davydov, explained that his compliance was due to hypocrisy, not piety, and complained about the communion fare:

my impious stomach

âFor pityâs sake, old chap,â remarks,

âIf only Christâs blood

Were, letâs say, Lafite â¦

Or Clos de Vougeot, then not a word,

But this â itâs just ridiculous â

Is Moldavian wine and water.â51

He greeted Easter with the irreverent poem âChrist is risenâ, addressed to the daughter of a Kishinev inn-keeper. Today he would exchange kisses with her in the Christian manner, but tomorrow, for another kiss, would be willing to adhere to âthe faith of Mosesâ, and even put into her hand âThat by which one can distinguish/A genuine Hebrew from the Orthodoxâ.52

At the beginning of May, in a letter to Aleksandr Turgenev, he jokingly suggested that the latter might use his influence to obtain a few daysâ leave for his exiled friend, adding: âI would bring you in reward a composition in the taste of the Apocalypse, and would dedicate it to you, Christ-loving pastor of our poetic flock.â* 53 The description of Turgenev alluded to the fact that he was the head of the Department of Foreign Creeds; the work Pushkin was proposing to dedicate to him was, however, hardly appropriate: it was The Gabrieliad, a blasphemous parody of the Annunciation.54

Far from Jerusalem lives the beautiful Mary, whose âsecret flowerâ âHer lazy husband with his old spout/In the mornings fails to waterâ. God sees her, and, falling in love, sends the archangel Gabriel down to announce this to her. Before Gabriel arrives, Satan appears in the guise of a snake; then, turning into a handsome young man, seduces her. Gabriel interrupts them; the two fight; Satan, vanquished by a bite âin that fatal spot/(Superfluous in almost every fight)/That haughty member, with which the devil sinnedâ (421â2), limps off, and his place and occupation are assumed by Gabriel. After his departure, as Mary is lying contemplatively on her bed, a white dove â God, in disguise â flies in at the window, and, despite her resistance, has its way with her.

Tired Mary

Thought: âWhat goings-on!

One, two, three! â how can they keep it up?

I must say, itâs been a busy time:

Iâve been had in one and the same day

By Satan, an Archangel and by God.â

(509â14)

It is slightly surprising to find the poem in Pushkinâs work at this time: the wit is not that of his current passion, Byron, but that of his former heroes, Voltaire and Parny; the blend of the blasphemous and the erotic is characteristic of the eighteenth, rather than the nineteenth century. Obviously it could not be published, but, like Pushkinâs political verses, was soon in circulation in manuscript.* Seven years later this lighthearted Voltairean anti-religious squib was to cause him almost as much trouble as his political verse had earlier.

Fasting seemed to stimulate Pushkinâs comic vein; during the following Lent, in 1822, he produced the short comic narrative poem âTsar Nikita and His Forty Daughtersâ.55 There is nothing blasphemous or anti-religious about this work; though it might be considered risqué or indecent, it is certainly not, as it has been called, âout-and-out pornographyâ.56 Written in the manner of a Russian fairy-tale, the poem tells us that Tsar Nikitaâs forty daughters, though uniformly captivating from head to toe, were all deficient in the same respect:

One thing was missing.

What was this?

Nothing in particular, a trifle, bagatelle,

Nothing or very little,

But it was missing, all the same.

How might one explain this,

So as not to anger

That devout pompous ninny,

The over-prim censor?

How is it to be done? ⦠Aid me, Lord!

The tsarevnas have between their legs â¦

No, thatâs far too precise

And dangerous to modesty, â

Letâs try another tack:

I love in Venus her breast,

Her lips, her ankle particularly,

But the steel that strikes loveâs spark,

The goal of my desire â¦

Is what? ⦠Nothing!

Nothing or very little â¦

And this wasnât present

In the young princesses,

Mischievous and lively.

Tsar Nikita is simpler, more of a jeu dâesprit than The Gabrieliad: it consists essentially of a number of variations on the same joke. But it is charmingly written, witty and highly amusing.

Pushkinâs readiness to take offence and his profligate way with a challenge were as evident in Kishinev as in St Petersburg. At the beginning of June 1821, having quarrelled with a former French officer, M. Déguilly, for some reason possibly connected with the latterâs wife, he called him out, but was incensed to discover the following day that his opponent had managed to weasel his way out of a duel. He dashed off an offensive letter in French, and unable to draw blood with his sabre, consoled himself by doing so with his pen, sketching a cartoon showing Déguilly, clad only in a shirt, exclaiming: âMy wife! ⦠my breeches! ⦠and my duel too! ⦠ah, well, let her get out of it how she will, since it is she who wears the breeches â¦â57

Other opponents were more worthy. One evening in January 1822, at a dance in the casino, Pushkinâs request that the orchestra should play a mazurka was countermanded by a young officer of the 33rd Jägers, who demanded a Russian quadrille. Shouts of âMazurka!â, âQuadrille!â alternated for some time; eventually the orchestra, though composed of army musicians, obeyed the civilian. Lieutenant-Colonel Starov, the commander of the Jäger regiment, told his officer that he should demand an apology. When the officer hesitated, Starov marched over to Pushkin, and, failing to receive satisfaction, arranged a meeting for the following morning. The duel took place a mile or two outside Kishinev, during a snowstorm: the driving snow and the cold made both aiming and loading difficult. They fired first at sixteen paces and both missed; then at twelve and missed again. Both contestants wished to continue, but their seconds insisted that the affair be postponed. On his return to Kishinev, Pushkin called on Aleksey Poltoratsky and, not finding him at home, dropped off a brief jingle: âIâm alive/Starovâs/Well./The duelâs not over.â58 In fact, it was: Poltoratsky and Nikolay Alekseev, who had acted as Pushkinâs second, arranged a meeting at Nikoletiâs restaurant, where Pushkin often played billiards, and a reconciliation took place. Pushkin swelled with pride when Starov, who had fought in the campaign of 1812 and was known for his bravery, complimented him on his behaviour: âYou have increased my respect for you,â he said, âand I must truthfully say that you stand up to bullets as well as you write.â59 According to Gorchakov, Pushkin displayed even more sangfroid at a duel fought in May or June 1823. This was with Zubov, an officer of the topographical survey, whom he had accused of cheating at cards. Pushkin, like his character the Count, in the short story âThe Shotâ, one of the Tales of Belkin, arrived with a hatful of cherries, which he ate while Zubov took the first shot. He missed. âAre you satisfied?â Pushkin asked. Zubov threw himself on him and embraced him. âThat is going too far,â said Pushkin, and walked off without taking his shot.60

The Starov affair had, however, unpleasant repercussions. Though the quarrel had been public, the duel and reconciliation were not; and it was rumoured, especially in Moldavian society, that both Starov and Pushkin had acted dishonourably. At an evening party some weeks later Pushkin light-heartedly referred to a remark made by Liprandi to the effect that Moldavians did not fight duels, but hired a couple of ruffians to thrash their enemy. Mariya Balsch, still smarting with jealousy, said acidly, âYou have an odd way of defending yourself, too,â adding that his duel with Starov had ended in a very peculiar manner. Pushkin, enraged, rushed off to Balsch, who was playing cards, and demanded satisfaction for the insult. Mariya complained of his behaviour to her husband, who, somewhat the worse for wine, himself flew into a rage, calling Pushkin a coward, a convict and worse. âThe scene [â¦] could not have been more terrible, Balsch was shouting and screaming, the old lady Bogdan fell down in a swoon, the vice-governorâs pregnant wife had hysterics.â61 The affair was reported to Inzov, who ordered that the two should be reconciled. Two days later they both appeared before the vice-governor, Krupensky; Major-General Pushchin was also present. When they met, Balsch said, âI have been forced to apologize to you. What kind of apology do you require?â Pushkin, without a word, slapped his face and drew out a pistol, before being led from the room by Pushchin.62 In a letter to Inzov Balsch demanded, firstly a safeguard against any further attempt which Pushkin might make on him, and, secondly, that the other should be proceeded against with the utmost rigour of the law.63 Whatever the rights of the situation, there was only one choice Inzov could make between an extremely junior civil servant and a Moldavian magnate: sending Pushkin to his quarters, he placed him under house arrest for three weeks.

Arguments were frequent at Inzovâs dinner table. A few months later, on 20 July 1822, when discussing politics with Smirnov, a translator, Pushkin âbecame heated, enraged and lost his temper. Abuse of all classes flew about. Civil councillors were villains and thieves, generals for the most part swine, only peasant farmers were honourable. Pushkin particularly attacked the nobility. They all ought to be hanged, and if this were to happen, he would have pleasure in tying the noose.â64 When both parties were heated with wine a possible explosion was never too far away. One occurred the following day, when the conversation at dinner touched upon the subject of hailstorms; whereupon a retired army captain named Rudkovsky claimed to have once witnessed a remarkable storm, during which hailstones weighing no less than three pounds apiece had fallen. Pushkin howled with laughter, Rudkovsky became indignant, and, after they had risen from table and Inzov had left, an exchange of insults led to an agreement to exchange shots. Both, accompanied by Smirnov, who had suffered Pushkinâs abuse the previous day, then went to Pushkinâs quarters, where some kind of fracas took place. Rudkovsky asserted that Pushkin attacked him with a knife, and Smirnov, agreeing, claimed to have managed to ward off the blow. Luckily no one was injured; however, Inzov, learning of the incident, put Pushkin under house arrest again.

General Orlov, âHymenâs shaven-headed recruitâ,65 had married Ekaterina Raevskaya in Kiev on 15 May 1821. Pushkin welcomed her arrival in Kishinev, and would visit the couple almost every day, lounging on their divan in wide Turkish velvet trousers, and conversing with them animatedly. He went riding with Orlov and fell off. âHe can only ride Pegasus or a nag from the Don,â the general commented to his wife. âPushkin no longer pretends to be cruel,â she wrote to her brother Aleksandr in November, âhe often calls on us to smoke his pipe and discourses or chats very pleasantly. He has only just completed an ode on Napoleon, which, in my humble opinion, is very good, as far as I can judge, having heard only part of it once.â66 Napoleon had died on 5 May 1821 (NS); the news of his death reached Kishinev in July.

The miraculous destiny has been accomplished;

The great man is no more.

In gloomy captivity has set

The terrible age of Napoleon,

Pushkin wrote.67 His earlier hatred of the emperor had been replaced, if not by the hero-worship of Romanticism, at least by awe and admiration.

Orlov was a humane and enlightened commander, who was particularly anxious to reduce the incidence of corporal punishment in the units under his command. He had surrounded himself by a number of like-minded officers: Pushchin, his second-in-command, was a Decembrist, as was Okhotnikov, his aide-de-camp. So too was Vladimir Raevsky, âa man of extraordinary energy, capabilities, very well-educated and no stranger to literatureâ:68 a distant relative of Pushkinâs friends. Born in 1795, Raevsky had entered the army at sixteen; in 1812, as an ensign in an artillery brigade, he had been awarded a gold sword for bravery at Borodino. Now a major in the 32nd Jägers, he was the divisionâs chief education officer, responsible for all its Lancaster schools.* This position gave him great influence on the rank-and-file of the division, and he employed it to inculcate what were considered to be dangerously subversive ideas. A later report on his activities singled out the fact that in handwriting exercises he used for examples words such as âfreedomâ, âequalityâ, and âconstitutionâ and alleged that he told officer cadets that constitutional government was better than any other form of government, and especially than Russian monarchic government, which, although called monarchic, was really despotic.69 A pedagogue by nature, he exposed the gaps in Pushkinâs knowledge, and was a severe critic of his verse.

In December 1821 Liprandi was ordered by Orlov to report on the condition of the 31st and 32nd Jäger regiments, stationed in Izmail and Akkerman at the mouth of the Dniester. He invited Pushkin to accompany him; Inzov, who had just been reprimanded for not keeping a strict watch over his protégé, at first refused his permission, but was persuaded by Orlov to change his mind.

Pushkin was full of historical enthusiasm when the two set off on 13 December. He was eager to stop in Bendery and visit the camp at Varnitsa, where Charles XII of Sweden had lived from 1709 to 1713, having taken refuge on Turkish territory after his defeat by Peter at Poltava â the battle which was to be the climax of, and provide the title for Pushkinâs long narrative poem of 1828â9. Liprandi, however, hurried him on. The next post-station, Kaushany, aroused his excitement again: this had been the seat, from the sixteenth century until 1806, of the khans who had ruled Budzhak, the southern region of Moldavia. But according to Liprandi there was nothing to see and, stopping only to change horses, they drove on.

They arrived in Akkerman early in the evening of the fourteenth, and went straight to dinner with Colonel Nepenin, the commander of the 32nd Jägers. Among the guests was an old St Petersburg acquaintance, Lieutenant-Colonel Pierre Courteau, now commandant of the fortress. He and Pushkin were both members of Kishinevâs short-lived Masonic lodge, Ovid, opened in the spring and closed â together with all other lodges in Bessarabia â in December by Inzov on the emperorâs orders. While Pushkin and Courteau were talking, Nepenin asked Liprandi in an undertone, audible to Pushkin, whether his friend was the author of A Dangerous Neighbour â the indecent little epic composed by Pushkinâs uncle, Vasily. Liprandi, embarrassed, and wishing to avoid further queries, replied that he was, but did not like to have it talked about. His ruse succeeded, the poem was not mentioned further; later that evening, however, Pushkin took him to task for his subterfuge, and called Nepenin an uneducated ignoramus for imagining that he, a twenty-two-year-old, could be the author of a poem which had been well-known ever since its composition ten years earlier, in 1811.

The following day, while Liprandi was inspecting the regiment, Pushkin was shown round the fortress by Courteau; they dined with him, and returned to their quarters in the early hours of the morning, after an evening spent at the card-table and in flirtation with the commandantâs âfive robust daughters, no longer in the bloom of youthâ.70 They left for Izmail early the following evening, arriving at ten at night and putting up with a Slovenian merchant, Slavic.

In 1791, during the Russo â Turkish war, Izmail had been stormed and captured by a Russian army commanded by Suvorov â an event celebrated by Byron in the seventh and eighth cantos of Don Juan. Pushkin was naturally impatient to inspect the scenes of the fighting: when Liprandi returned to their lodging the next evening he found that his companion had already been round the fortress with SlaviÄ; he was amazed that the besiegers had managed to scale the fortifications facing the Danube. He had also taken down a Slovenian song from the dictation of their hostâs sister-in-law, Irena. The following morning Liprandi, before leaving to inspect the 31st Jägers, introduced Pushkin to a naval lieutenant in the Danube flotilla, Ivan Gamaley; together they visited the town, the fortress and the quarantine station; were taken to the casino by SlaviÄ, and then had supper at his house with another naval lieutenant, Vasily Shcherbachev. Returning at midnight, Liprandi found Pushkin sitting cross-legged on a divan, surrounded by a large number of little pieces of paper. When asked whether he had got hold of Irenaâs curling papers, Pushkin laughed, shuffled them together and hid them under a cushion; the two emptied a decanter of local wine and went to bed. In the morning Liprandi awoke to find Pushkin, unclothed, sitting in the same posture as the previous night, again surrounded by his pieces of paper, but holding a pen in his hand with which he was beating time as he recited, nodding his head in unison. Noticing that Liprandi was awake, he stopped and gathered up his papers; he had been caught in the act of composition. That morning Liprandi, after writing his report, called on Major-General Tuchkov, who expressed the wish to meet Pushkin. He came to dinner at their lodgings and afterwards bore off Pushkin, who returned at ten in the evening, somewhat out of sorts; he wished he could stay here a month to examine properly everything the general had shown him. âHe has all the classics and extracts from them,â he told Liprandi, who jokingly suggested that he was more interested in Irenaâs classical forms.71

The next morning they set out for Kishinev. Late that evening, as Pushkin was dozing in his corner of the carriage, Liprandi remarked that it was a pity it was so dark, as otherwise they could have seen to the left the site of the battle of Kagul: here in August 1770 General Rumyantsev with 17,000 men engaged the main Turkish army, winning a hard-fought battle with the bayonet and capturing the Turkish camp. Pushkin immediately started to life, animatedly discussed the battle, and quoted a few lines of verse â perhaps those from his Lycée poem, âRecollections in Tsarskoe Seloâ, in which he mentions the monument to the battle in the palace park:

In the thick shade of gloomy pines

Rises a simple monument.

O, how shameful for thee, Kagulian shore!

And glorious for our dear native land!72

Arriving in Leovo before midday, they called on Lieutenant-Colonel Katasanov, the commander of the Cossack regiment stationed here. He was away, but his adjutant insisted that they should stay for lunch: caviare, smoked sturgeon â of which Pushkin was inordinately fond â and vodka appeared, succeeded by partridge soup and roast chicken. Half an hour after their departure Pushkin, who had been in a brown study, suddenly burst into such raucous and prolonged laughter that Liprandi thought he was having a fit. âI love cossacks because they are so individual and donât keep to the normal rules of taste,â he said. âWe â indeed everyone else â would have made soup from the chicken and would have roasted the partridge, but they did the opposite!â73 He was so struck by this that after his return to Kishinev â they arrived at nine that evening, 23 December â he sought out the French chef Tardif â âinexhaustible in ideas/For entremets, or for piesâ74 â then living on Gorchakovâs charity,* to tell him about it, and two years later, in Odessa, reminded Liprandi of the meal.

During the winter the training battalion of the 16th division had been employed in constructing, at Orlovâs expense, a manège, or riding-school. Its ceremonial opening took place on New Yearâs Day 1822. Liprandi and Okhotnikov had decorated the interior: the walls were hung with bayonets, swords, muskets; on that opposite the entrance was a large shield, with a cannon and heap of cannon-balls to each side; in the centre was the monogram of Alexander, done in pistols, surrounded by a sunburst of ramrods, and flanked by the colours of the Kamchatka and Okhotsk regiments. Before this was a table, laid for forty guests, while eight other tables, four down each side of the hall, were to accommodate the training battalion. Inzov and his officials â including Pushkin â and the town notables were invited. The building was blessed by Archbishop Dimitry and after the ceremony all sat down to a breakfast. âThere was no lack of champagne or vodka. Some felt a buzzing in their heads, but all departed decorously.â75 A week later Orlov and Ekaterina left for Kiev, where they were to stay for some time. As it turned out, the absence of the divisionâs commander at this moment was unfortunate.

The 16th division was part of the 6th Corps, commanded by Lieutenant-General Sabaneev, whose headquarters were at Tiraspol, halfway between Kishinev and Odessa. Over the previous six months General Kiselev, the chief of staff of the Second Army, had stepped up surveillance of the armyâs units: he was particularly concerned about the 16th division, commanded as it was by such a noted liberal. Despite his friendship with Orlov, he had cautiously insinuated to Wittgenstein, the commander of the army, that the latter was unsuited to the command of the division. Raevsky, too, had come to his attention. âI have long had under observation a certain Raevsky, a major of the 32nd Jäger regiment, who is known to me by his completely unrestrained freethinking. At the present moment in agreement with Sabaneev an overt and covert investigation of all his actions is taking place, and he will, it seems, not escape trial and exile.â76

In Orlovâs absence General Sabaneev â a short, choleric fifty-two-year-old with a red nose, ginger hair and side-whiskers â began to pay frequent visits to Kishinev. He dined with Inzov on 15 January. Pushkin was present, but was uncharacteristically silent during the meal. Sabaneev was in Kishinev again on the twentieth, when he wrote to Kiselev: âThere is no one in the Kishinev gang besides those whom you know about, but what aim this gang has I do not as yet know. That well-known puppy Pushkin cries me up all over town as one of the Carbonari, and proclaims me guilty of every disorder. Of course, it is not unintentional, and I suspect him of being an organ of the gang.â77

On 5 February, at nine in the evening, Raevsky was reclining on his divan and smoking a pipe when there was a knock on the door; his Albanian servant let in Pushkin. He had, he told Raevsky, just eavesdropped on a conversation between Inzov and Sabaneev. Raevsky was to be arrested in the morning. âTo arrest a staff officer on suspicion alone has the whiff of a Turkish punishment. However, what will be, will be,â Raevsky remarked. Lost in admiration at his coolness, Pushkin attempted to embrace him. âYouâre no Greek girl,â said Raevsky, pushing him away. The two went round to Liprandi, who was entertaining a number of guests, including his younger brother, Pavel, Sabaneevâs adjutant. When Raevsky and Pushkin entered, they were assailed with questions as to what was going on. âAsk Pavel Petrovich,â Raevsky replied, âhe is Sabaneevâs trusted plenipotentiary minister.â âTrue,â said the younger Liprandi, âbut if Sabaneev trusted you as he trusts me, you too would not wish to break the codes of trust and honour.â78 At noon the next day he was summoned to Sabaneev, and confronted with three officer cadets, members of his Lancaster school, whose testimony as to his teaching was the ostensible reason for his arrest. His books and papers were confiscated and a guard put on his quarters. A week later he was taken to Tiraspol and lodged in a cell in the fortress. The investigation into his case and his trial dragged on for years. Only in 1827 was he finally sentenced to exile in Siberia. In March Major-General Pushchin was relieved of his command of a brigade in Orlovâs division, and the following April Kiselev succeeded in bringing about Orlovâs removal from his command.

In July 1822 Liprandi, passing through Tiraspol on his way from Odessa to Kishinev, managed, with the connivance of the commandant of the fortress, to have half an hourâs conversation with Raevsky as they strolled backwards and forwards over the glacis. Raevsky gave him a poem, âThe Bard in the Dungeonâ, to pass on to Pushkin, who was particularly impressed by one stanza:

Like an automaton, the dumb nation

Sleeps in secret fear beneath the yoke:

Over it a bloody clan of scourges

Both thoughts and looks executes on the block.

Reading it aloud to Liprandi, he repeated the last line, and added with a sigh: âAfter such verses we will not see this Spartan again soon.â79

Although the authorities knew that Raevsky was a member of some kind of conspiracy, he remained resolutely silent in prison, and no other arrest followed his. Pushkin was surprised and shocked by the incident, which in addition appeared to him deeply mysterious: the severity of Raevskyâs treatment seemed wholly out of proportion to his crime. It was only in January 1825, when his old Lycée friend Pushchin visited him in Mikhailovskoe, that he gained some inkling of what had been going on. âImperceptibly we again came to touch on his suspicions concerning the society,â writes Pushchin. âWhen I told him that I was far from alone in joining this new service to the fatherland, he leapt from his chair and shouted: âThis must all be connected with Major Raevsky, who has been sitting in the fort at Tiraspol for four years and whom they cannot get anything out of.ââ80

In December 1820 Pushkin had written from Kamenka to Gnedich, the publisher of Ruslan and Lyudmila, to tell him that his next narrative poem, The Prisoner of the Caucasus, was nearly completed. He was unduly optimistic; it was not until the following March that he wrote again. âThe setting of my poem should have been the banks of the noisy Terek, on the frontier of Georgia, in the remote valleys of the Caucasus â I placed my hero in the monotonous plains where I myself spent two months â where far distant from one another four mountains rise, the last spur of the Caucasus; â there are no more than 700 lines in the whole poem â I will send it you soon â so that you might do with it what you like.â81 Before long, however, he was having second thoughts; he was in need of money and, compared to Gnedich, had made little out of Ruslan. In September he wrote to Grech, editor of Son of the Fatherland. âI wanted to send you an extract from my Caucasian Prisoner, but am too lazy to copy it out; would you like to buy the poem from me in one piece? It is 800 lines long; each line is four feet wide; it is chopped into two cantos. I am letting it go cheaply, so that the goods do not get stale.â82 Unfortunately, Gnedich got wind of the offer. âYou tell me that Gnedich is angry with me,â he wrote to his brother in January 1822, âhe is right â I should have gone to him with my new narrative poem â but my head was spinning â I had not heard from him for a long time; I had to write to Grech â and using this dependable occasion* I offered him the Captive ⦠Besides, Gnedich will not haggle with me, nor I with Gnedich, each of us over-concerned with his own advantage, whereas I would have haggled as shamelessly with Grech as with any other bearded connoisseur of the literary imagination.â83 He also made an attempt to sell the poem directly to book-sellers in St Petersburg, but, offered a derisory sum, had to fall back on Gnedich. On 29 April he sent him the manuscript, accompanying it with a letter which began âParve (nec invideo) sine me, liber, ibis in urbem,/Heu mihi! quo domino non licet ireâ â the opening lines of Ovidâs Tristia,â â and continued: âExalted poet, enlightened connoisseur of poets, I hand over to you my Caucasian prisoner [â¦] Call this work a fable, a story, a poem or call it nothing at all, publish it in two cantos or in only one, with a preface or without; I put it completely at your disposal.â84

Pushkinâs friends knew that he had been at work on a successor to Ruslan: âPushkin has written another long poem, The Prisoner of the Caucasus,â Turgenev had told Dmitriev the previous May; âbut he has not mended his behaviour: he is determined to resemble Byron not in talent alone.â85 When the manuscript arrived in St Petersburg, it was bitterly fought over. âI have not set eyes on the Caucasian captive,â Zhukovsky complained to Gnedich at the end of May; âTurgenev, who has no interest in reading himself, but only in taking other peopleâs verse around on visits, has decided not to send me the poem, since he is afraid of letting it out of his claws, lest I (and not he) should show it to someone. I beg you to let me have it as soon as possible; I will not keep it for more than a day and will return it immediately.â86 Turgenev eventually did take the poem out to Zhukovsky in Pavlovsk, but Vyazemsky, who had been clamouring for it â âThe Captive, for Godâs sake, just for one post,â he implored Turgenev87 â had to wait until publication.

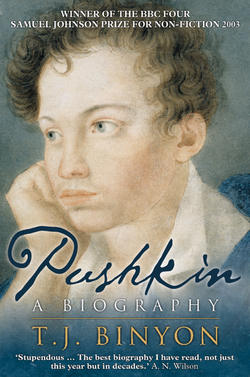

The Prisoner of the Caucasus came out on 14 August â a small book of fifty-three pages, costing five roubles, or seven if on vellum. A note at the end of the poem read: âThe editors have added a portrait of the author, drawn from him in youth. They believe that it is pleasing to preserve the youthful features of a poet whose first works are marked by so unusual a talent.â88 The portrait, engraved by Geitman, depicts Pushkin âat fifteen, as a Lycéen, in a shirt, as Byron was then drawn, with his chin on his hand, in meditationâ.89 Gnedich, more expeditious than before, sent him a single copy of the poem in September, together with a copy of Zhukovskyâs translation of Byronâs The Prisoner of Chillon. Pushkin wrote to him on 27 September: âThe Prisoners have arrived â and I thank you cordially, dear Nikolay Ivanovich [â¦] Aleksandr Pushkin is lithographed in masterly fashion, but I do not know whether it is like him, the editorsâ note is very flattering, but I do not know whether it is just.â90 The edition â probably of 1,200 copies â sold out with remarkable speed: in 1825 Pletnev, searching for a copy to send to Pushkin in Mikhailovskoe, could not find one. Of the profit Gnedich sent Pushkin 500 roubles, keeping, it has been calculated, 5,000 for himself.91 This time he had been too sharp. The following August Pushkin wrote to Vyazemsky; âGnedich wants to buy a second edition of Ruslan and The Prisoner of the Caucasus from me â but timeo danaos,* i.e., I am afraid lest he should treat me as before.â92 Gnedich did not get the rights: The Prisoner was the last of Pushkinâs works he published.

Its plot is not difficult to recapitulate: a Russian journeying in the Caucasus is captured by a Circassian tribe; a young girl falls in love with the captive, but he cannot return her feeling. Nevertheless, she aids him to escape: he swims the river and reaches the Russian lines; she drowns herself. In a letter to Lev describing his journey through the Caucasus Pushkin had toyed with the fancy of a Russian general falling prey to a Circassianâs lasso. The fancy becomes real in the poemâs opening lines; but the plot might also owe something to Chateaubriandâs Atala (1801), in which an American Indian, made prisoner by another tribe and about to be burnt at the stake, is freed by a native girl, with whom he flees; she later commits suicide. The poemâs hero is a Byronic figure, and the poem itself resembles Byronâs eastern poems, The Bride of Abydos, The Giaour and particularly The Corsair. Pushkin, however, undercuts Romantic ideology with an ironic paradox: fleeing the corruption and deceit of society to search for freedom in a wild and exotic region peopled by man in his natural state, the hero becomes a prisoner of the mountain tribesmen who incarnate his ideal. There is, too, a peculiar ideological discrepancy between the poem and its epilogue, written in Odessa in May 1821. This preaches an imperial message, celebrating the pacification of the Caucasus, and praising the Russian generals who forcibly subdued the tribes. Vyazemsky was shocked. âIt is a pity that Pushkin should have bloodied the final lines of his story,â he wrote to Turgenev. âWhat kind of heroes are Kotlyarevsky and Ermolov? What is good in the fact that he âlike a black plague,/Destroyed, annihilated the tribesâ? Such fame causes oneâs blood to freeze in oneâs veins, and oneâs hair to stand on end. If we had educated the tribes, then there would be something to sing. Poetry is not the ally of executioners; they may be necessary in politics, and then it is for the judgement of history to decide whether it was justified or not; but the hymns of a poet should never be eulogies of butchery. I am annoyed with Pushkin, such enthusiasm is a real anachronism.â93

Anachronistic or not, these were definitely Pushkinâs views. âThe Caucasian region, the sultry frontier of Asia, is curious in every respect,â he had written in 1820. âErmolov has filled it with his name and beneficent genius. The savage Circassians have become frightened; their ancient audacity is disappearing. The roads are becoming safer by the hour, and the numerous convoys are superfluous. One must hope that this conquered region, which up to now has brought no real good to Russia, will soon through safe trading bring us close to the Persians, and in future wars will not be an obstacle to us â and, perhaps, Napoleonâs chimerical plan for the conquest of India will come true for us.â94 He obviously could see no contradiction between his fiery support of Greek independence and his equally fiery desire to eradicate Caucasian independence; nor between his whole-hearted support of the government here and his equally whole-hearted denunciation of the government everywhere else. In fact, some of the Decembrists shared his view that the Caucasus could not be independent: Pestel, in his Russian Justice, writes that some neighbouring lands âmust be united to Russia for the firm establishment of state securityâ, and names among them: âthose lands of the Caucasian mountain peoples, not subject to Russia, which lie to the north of the Persian and Turkish frontiers, including the western littoral of the Caucasus, presently belonging to Turkeyâ.95 They did not, however, share his chimerical Indian plan, nor the pleasure â the real stumbling-block for Vyazemsky â which he apparently took in genocide.

âTell me, my dear, is my Prisoner making a sensation?â he asked his brother in October 1822. âHas it produced a scandal, Orlov writes, that is the essential. I hope the critics will not leave the Prisonerâs character in peace, he was created for them, my dear fellow.â96 He was to be disappointed: there was no critical polemic over the poem, as there had been over Ruslan and Lyudmila. The Byronic poem had ceased to be a novelty; Pushkinâs reputation was now more firmly established, and, above all, The Prisoner did not have that awkward contrast between present-day narrator and past narrative which had worried some critics, nor that equally awkward comic intent, which had worried others. Praise was almost unanimous. In September Pushkinâs uncle wrote to Vyazemsky: âHere is what our La Fontaine [Dmitriev] writes to our Livy [Karamzin]: âYesterday I read in one breath The Prisoner of the Caucasus and from the bottom of my heart wished the young poet a long life! What a prospect! Right at the beginning two proper narrative poems, and what sweetness in the verse! Everything is picturesque, full of feeling and wit!â I confess, that reading this letter, I shed a tear of joy.â97 Karamzin was slightly less enthusiastic. âIn the poem of that liberal Pushkin The Prisoner of the Caucasus the style is picturesque: I am dissatisfied only with the love intrigue. He really has a splendid talent: what a pity that there is no order and peace in his soul and not the slightest sense in his head.â98 Of the critics only Mikhail Pogodin, in the Herald of Europe, descended to the kind of pedantic quibbling that had characterized reviews of Ruslan. Of the lines âNeath his wet burka, in the smoky hut/The traveller enjoys peaceful sleepâ (I, 321â2), he remarks: âHe would be better advised to throw off his wet burka [a felt cloak, worn in the Caucasus], and dry himself.â99 Pushkinâs comment, when meditating corrections for a second edition, was: âA burka is waterproof and gets wet only on the surface, therefore one can sleep under it when one has nothing better to cover oneself with.â100

Where dissatisfaction was felt, it was, as in Karamzinâs case, with the love intrigue: the character of the hero, and the fate of the heroine. In the second edition of 1828 Pushkin inserted a note: âThe author also agrees with the general opinion of the critics, who justifiably condemned the character of the prisonerâ;101 and in 1830 wrote: âThe Prisoner of the Caucasus is the first, unsuccessful attempt at character, which I had difficulty in managing; it was received better than anything I had written, thanks to some elegiac and descriptive verses. But on the other hand Nikolay and Aleksandr Raevsky and I had a good laugh over it.â102 âThe character of the Prisoner is not a success; this proves that I am not cut out to be the hero of a Romantic poem. In him I wanted to portray that indifference to life and its pleasures, that premature senility of soul, which have become characteristic traits of nineteenth-century youth,â he wrote to Gorchakov.103 Criticism of the fate of the Circassian maiden, however, he met with some irony: to Vyazemsky, after thanking him for his review* â âYou cannot imagine how pleasant it is to read the opinion of an intelligent person about oneselfâ â he wrote: â[Chaadaev] gave me a dressing-down for the prisoner, he finds him insufficiently blasé; unfortunately Chaadaev is a connoisseur in that respect [â¦] Others are annoyed that the Prisoner did not throw himself into the water to pull out my Circassian girl â yes, you try; I have swum in Caucasian rivers, â youâll drown yourself before you find anything; my prisoner is an intelligent man, sensible, not in love with the Circassian girl â he is right not to drown himself.â104

âIn general I am very dissatisfied with my poem and consider it far inferior to Ruslan,â he told Gorchakov.105 He was right: The Prisoner has none of the wit, the gaiety and the grace of the earlier poem; he was not âcut out to be the hero of a Romantic poemâ. But a combination of circumstances â his reading of Byron, his acquaintance with Aleksandr Raevsky, his exile â had led him down a blind alley: it was still to take him some time to retrace his steps fully. A significant move in this direction took place when, on 9 May 1823, he began Eugene Onegin. At the head of the first stanza in the manuscript this date is noted with a large, portentously shaped and heavily inked numeral. It was a significant, indeed fatidic date in Pushkinâs life: on 9 May 1820, according to his calendar, his exile from St Petersburg had begun. He usually worked on the poem in the early morning, before getting up. Visitors found him, as Liprandi had glimpsed him in Izmail, sitting cross-legged on his bed, surrounded by scraps of papers, ânow meditative, now bursting with laughter over a stanzaâ.106 âAt my leisure I am writing a new poem, Eugene Onegin, in which I am transported by bile,â he told Turgenev some months later.107

Meanwhile changes in the regionâs administration were taking place. On 7 May 1823 Alexander signed an order freeing Inzov from his duties and appointing Count Mikhail Vorontsov governor-general of New Russia and of Bessarabia. Informing Vyazemsky of this, Turgenev wrote: âI do not yet know whether the Arabian devil* will be transferred to him. He was, it seems, appointed to Inzov personally.â âHave you spoken to Vorontsov about Pushkin?â Vyazemsky asked. âIt is absolutely necessary that he should take him on. Petition him, good people! All the more as Pushkin really does want to settle down, and boredom and vexation are bad counsellors.â Turgenevâs agitation was successful. âThis is what happened about Pushkin. Knowing politics and fearing the powerful of this world, consequently Vorontsov as well, I did not want to speak to him, but said to Nesselrode under the guise of doubt, whom should he be with: Vorontsov or Inzov. Count Nesselrode affirmed the former, and I advised him to tell Vorontsov of this. No sooner said than done. Afterwards I myself spoke twice with Vorontsov, explained Pushkin to him and what was necessary for his salvation. All, it seems, should go well. A Maecenas, the climate, the sea, historical reminiscences â there is everything; there is no lack of talent, as long as he does not choke to death.â108

Unaware of these machinations, Pushkin had successfully requested permission to spend some time in Odessa: the excuse being that he needed to take sea baths for his health. He arrived at the beginning of July and put up at the Hotel du Nord on Italyanskaya Street. âI left my Moldavia and appeared in Europe â the restaurants and Italian opera reminded me of old times and by God refreshed my soulâ. Vorontsov and his suite arrived on the evening of 21 July. The following day Vorontsov summoned him to his presence. âHe receives me very affably, declares to me that I am being transferred to his command, that I will remain in Odessa â this seems fine to me â but a new sadness wrung my bosom â I began to regret my abandoned chains.â* On the twenty-fourth a large ball was given in honour of Vorontsov by the Odessa Chamber of Commerce; on the twenty-sixth Vorontsov and his suite, now including Pushkin, left for Kishinev, where, two days later, Inzov handed over his post to his successor. Pushkin had time to collect his salary before accompanying the new governor-general back to Odessa at the beginning of August. âI travelled to Kishinev for a few days, spent them in indescribably elegiac fashion â and, having left there for good, sighed after Kishinev.â109

* Written in November 1820 and published the following year, âThe Black Shawlâ, in which a jealous lover kills his Greek mistress and her Armenian paramour, became, though an indifferent work, one of Pushkinâs most popular poems. It was set to music by the composer Aleksey Verstovsky in 1824, and often performed.

* It is thought that Pushkin might have paid a second visit to Kamenka, Kiev, and possibly Tulchin in November-December 1822, but there is no direct evidence as to his whereabouts at this time. The arguments supporting the hypothesis are summarized in Letopis, I, 504â5.

â From the Phanari, or lighthouse quarter of Constantinople, which became the Greek quarter after the Turkish conquest: and hence the appellation of the Greek official class under the Turks, through whom the affairs of the Christian population in the Ottoman empire were largely administered.

* A slip of the pen: there were approximately 25,000 Turks in the Morea.