Читать книгу Siege 13 - Tamas Dobozy - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

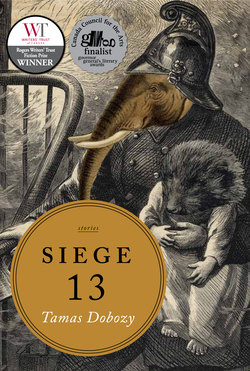

ОглавлениеThe Atlas of B. Görbe

E WAS THE SORT OF MAN you’ve seen: big and fat in an overcoat beaded with rain, cigar poking from between his jowls, staring at some vision beyond the neon and noise and commuter frenzy of Times Square.

That’s how Benedek Görbe looked the last time I saw him. This was May, 2007, shortly before I left Manhattan, where I’d been living with my family for six months on a Fulbright fellowship at NYU. Görbe was an ex-boyfriend of an aunt in Budapest, though he hadn’t lived in or visited Hungary for over forty years. He wrote in Hungarian every day though, along with drawing illustrations, for a series of kids’ books published under the name B. Görbe by a small but quality imprint out of Brooklyn who’d hired a translator and published them in enormous folio-sized hardcovers under the title The Atlas of Dreams. Benjamin and Henry, my two boys, loved the books, with their pictures reminiscent of fin de siècle posters, stories of children climbing ladders into dreams—endless garden cities, drifting minarets, kings shrouded in hyacinths. That was Görbe’s style, not that you’d have known it from the way he looked—with his stubble, pants the size of garbage bags, half-smouldering cigars, his obnoxious way of disagreeing with any opinion that wasn’t his own, and sometimes, after a moment’s reflection, even with that.

I was drawn to Görbe out of disappointment. The position at NYU had promised “a stimulating artistic environment,” though what it actually gave me was an office in the back of a building where a bunch of important writers were squirrelled away writing, when they were there at all. In the end I wasn’t surprised; that’s what writers did—they worked. But this meant that when I wasn’t writing I was wandering the streets, sometimes alone, sometimes with my wife, Marcy, in a dreamscape very different from the one described by Görbe. Rather than climbing up a ladder, I felt as if I’d climbed down one, into spaces of concrete and brick, asphalt and iron, and because it was winter it was always snowing, then rain, always torrential. I don’t mean to imply that New York was dreary, only that it seemed emptied, an abandoned city, which is odd since there were people everywhere—to the point where I sometimes couldn’t move along the sidewalk—all of them rushing by me as if they knew something I didn’t, as if every street and avenue offered a series of doors only they could open. Because of this, because so much seemed inaccessible, New York made me feel as if I was a kid again, left alone at home for the first time, or in the house of a stranger, on a grey Sunday when there’s nothing to do but search through the closets and cabinets of rooms you’re not supposed to go into, never coming upon anything of interest but always hoping the next jewellry box or armoire or night-stand will redeem the lost afternoon. New York—my New York that winter—was a place of secrets.

Görbe was the biggest of them all. I called him on advice from my aunt Bea, who gave me his phone number after I complained about how few contacts I was making. She’d dated him, unbelievably enough, back in university in Budapest during the early 1960s. Görbe was an art student then, though he was also taking courses in literature and history and whatever else fired his imagination. He was “quiet and dreamy,” according to my aunt, but also “very handsome.” She compared him to Montgomery Clift. In the end, they only went out for ten months, after which Görbe dumped her for the supposed love of his life, a woman called Zella, who was majoring in psychology and who kept, according to rumour, the dream diary that would inspire Görbe’s writing. Within a year of meeting Zella, Görbe left university without a degree, disappearing from my aunt’s life for five years before resurfacing when his first book was published. My aunt went to the launch, wandering past posters of his illustrations, amazed to see how much Görbe had changed. Gone was the easy smile, that faraway look he sometimes had. There was something frantic about him that day, my aunt said, but he was as handsome as ever, and though he never revealed what the trouble was he seemed happy to have someone from the past to talk to. Görbe was especially bad-tempered when people who hadn’t bought a book came up to him. “I was surprised to see him like that,” she said. “When I knew him in university he was so different. We were hardly adults then, but we were on the edge of it—university degrees, jobs, marriages, children—but whenever I was with him it always felt to me as if we were back in the garden in Mátyásföld, playing hide-and-seek, climbing the downspout to the roof, searching for treasures in the attic.” My aunt paused on the other end of the line. “Well, he’s become an important man, and maybe he could help you. It doesn’t sound like you’re having much luck there.” She paused again, and I could hear her shifting the phone against her face. “The number I have for him is quite old. He used to call me once in a while when he first left Hungary. I always got the feeling he really missed it here, that he didn’t want to go, and he always asked me to describe what the city was like, the changes that had happened. I think it was because of Zella that he went.” I could hear her rummaging on the other end of the line. “He hasn’t called me in years.”

When I finally telephoned Görbe he hesitated on the line, pretending not to remember my aunt, then grew curious when I rejected his suggestion that instead of bothering him I try to meet writers at the Hungarian Cultural Center. “I’m boycotting the place,” I said, explaining how I’d gone three weeks prior to see György Konrád and afterwards spoke with the centre’s director, László somebody or other, about my writing, and he’d faked interest, even enthusiasm, in that way they do so well in New York. This László person had advised me to put together an email with excerpts from my books and reviews, and to send it to him, and he’d get back to me. Hunting down the quotes and composing the email took the better part of a day, but László never responded—not to the email, not to the follow-up, nothing. “With all the time and bother it took, I could have taken my kids to the park,” I said, “or gone to the Met with Marcy—a hundred different things.”

Görbe laughed. It was like listening to a shout at the end of a long drainpipe. “Defaulting to the wife and kids, huh?” he said. “Listen, I hate the centre too. The programming . . . well, it’s like being inside a mind the size of a walnut. And the women they have working the bar—it would kill them to smile. I never go there anymore.”

“Uh . . .” I said.

“You’re petty and embittered, kid,” he shouted into the phone. “Running on despair. Narcissistic. Vindictive. I love it! Listen, you like Jew food?”

“Sure,” I said.

“Your wife and kids, they’re coming too, right?” He chuckled. “Before I help a writer I need to see what his home life is like.”

It was a strange request, but it didn’t take me long during that dinner at Carnegie’s to see that he loved kids, my kids, and had a way of hitting all the right spots with Marcy’s sense of humour—she was always amused by men who magnified their idiosyncrasies to comic levels—and before I knew it, before I’d even decided if I wanted to be friends with Görbe, she’d invited him to our place for dinner the next weekend. After that, with how much the kids loved him, and his attention to Marcy, we began seeing him regularly.

All of Görbe’s books feature the same three protagonists: a six-year-old boy named Fritz, a girl the same age named Susanna, and a kindly court jester who’s all of four years old, but whose illogical brain is perfect for figuring out the dream world and so is the wisest of them all. In the early books, the stories are about Fritz and Susanna falling asleep at night only to end up in the same dream. They spend the rest of the adventure trying to escape (with the jester’s help of course). As the books go on and the children’s home lives are revealed—dire poverty, Fritz’s absent mother and sullen father, Susanna’s illness (what in the early twentieth century was called “neurasthenia”), the cruelty of school—Fritz and Susanna decide they don’t want to wake up, they want to stay asleep, and the later stories are haunted by the fear that what separates dream from reality is as thin as tissue, and once it’s torn they’ll never again find their way back to the jester and the endless continents of sleep. The latest book ends with the two children coming upon a strange machine that will keep them there forever—if only they can figure out how to use it.

That’s the eleventh book in the series. It was published last year after we returned to Kitchener. I remember sitting with Benjamin in Words Worth Books on a snowy January day going through the illustrations and story and coming to the end, where Benjamin lingered, tracing his finger along the illustration of the dream machine, and finally said, “It was different when he read it to us.” I looked at him, wondering what he was talking about, because all I remembered of Görbe’s voice was the volume and rancid tobacco on his breath. It was Benjamin who reminded me that when Görbe read to him—as opposed to when Görbe spoke to me—his tone became quiet, it had a breathlessness to it, as if he too had no idea how the story would end and was as eager as any kid to find out. “You’re right,” I said, remembering those early nights in our apartment, “he did read that way,” my children tucked under each of his beefy arms.

When he was done reading to them Görbe would grumble and rub his eyes like someone forced out of bed too early, which was funny because he was never available before one o’clock, and I always guessed (wrongly as it turned out) that mornings were when he did his writing and drawing. Then he’d bite his cigar and look at me and ask if I was up for a “girlie drink,” which was the term he used for the awful cocktails he ordered. I think he discovered most of them in antique bartending manuals—like many children’s authors he was drawn to things discarded or forgotten—concoctions such as Sherry Cobbler, Pisco Punch, New Orleans Zazerac. The bartenders looked at him as if he was totally insane.

Once we were in the bar—any bar, though mostly we hung out at a tiny place in the East Village called Lotus—anything could happen. Görbe’s mouth was too big. He purposefully said things to outrage people, and most of the customers in the bars knew him on sight. He was a good fighter with fists as well as words—there was a lot of weight behind each punch, he was slow on his feet but able to withstand punishment, and only needed to connect once to knock you down. “You’re right,” he said to me once. “New York is a deserted city.” He looked at the bartender. “You’re a writer so you’ve probably seen it in the Times—that trembling subtext—where the critics complain that writers have failed to properly commemorate the tragic”—he winked at me—“event of six years ago.” He called to the bartender for another Philadelphia Fish-House Punch, then continued: “What they’re really bothered by is that it didn’t have the effect they wanted it to have. Except for a few months of public tears and outrage and the constant refrain by writers trying to prove 9/11 was of enormous significance, the only difference I see is that people around here go shopping even more than they did before.” He raised his voice and looked around the room. “It was significant to the friends and relatives of the deceased, of course, and to everyone else for a little while—a shock to the privileged and entitled who thought such a thing could never happen to them.” He looked back at me. “But go out on the street now,” he said. “Do you see any effect, really, out there? It passed right through them as if they were intangible.” He sipped his drink. “Once in a while someone tries to write something profound about it, and they always fail, and the critics are always angry that they didn’t do it justice. And all I can think is: Oh, New York, get over yourself!” He adopted a stage whisper: “What they can’t face, none of them, is its insignificance. People died in an act of war. Wow! How unusual!” He said the last three words so loud I jumped off my seat. “It’s terrible—” he pretended to wipe away tears “—now, can you please give me directions to the Louis Vuitton store?” Görbe snorted, staring back at the bartender. “It passed through them like they were ghosts,” he said. “As it should have.” He nodded. “As it should have.”

Görbe grunted and shifted on his stool and for a second I thought I saw something there, a break in the front he was putting on. “Listen, I lived through events a million times worse in Hungary—the war, the siege—like a lot of people. It wasn’t one day, it was six years, and, believe me, it didn’t lead to any great spiritual awakening!” He waved his hands in the air. “It happened. It was bad. And afterwards? Well, it will happen again. And in between you forget. You go back to your entertainments and schemes and obsessions and carry on. And that,” he said, “is all there is to say about it.”

Görbe rose drunkenly from his stool and bowed this way and that to the regulars, who didn’t know whether to applaud or tear him apart.

His reputation for outrage extended even to the world of children’s literature, which is no easy thing. When Görbe gave readings it wasn’t rare to see a crowd of a hundred or more in attendance, and not the usual moms and dads and kids and teachers, but people you’d never have expected—Brooklyn hipsters, businessmen in blue suits, specialty booksellers with stacks of first editions Görbe would sign and they’d sell at inflated prices (they all had to put a wad of bills on his outstretched palm before he signed anything), and even some skeletal blondes cradling tiny dogs that trembled so bad they looked as if they were going to disintegrate. Each one was crazy about Görbe, many knew him personally, and when they lined up to have books signed he made sure to say something memorable to every one, statements so outrageous I was sure someone would burst into tears, either that or assault him. Instead they only laughed or turned to friends and said, “See! What did I tell you?” and Görbe nodded almost imperceptibly, made a flourish with his pen, and handed back the book. It seemed to me, looking at the lineup, that they loved him, and it was only later, near the end of the night, after I realized I hadn’t seen one person open a book, or overheard a single comment about the writing, that I realized what was beneath it all: a fascination that was all about Görbe’s appearance and character. It was him they were there for. The signings were one of those New York events you went to to prove your coolness. Worst of all, I sensed Görbe not only knew this but encouraged it, as if he spent as much time rehearsing the crazy diatribes and remarks—like some kind of comedy routine—as he did writing the books. This, too, was part of the process.

During his career Görbe had sold millions of books, gone on innumerable book tours, and the few times he invited me to his apartment in Queens I peeked at some of the royalty cheques on his desk, amazed to think he made that much and still lived in such a hole. There were only two places in the apartment that made it look as if he hadn’t given up on life: the draughtsman’s table where he did his work, spotlessly clean, the various tools neatly organized; and the mantelpiece where photographs of his wife, Zella, sat carefully arranged so each image could be seen in its frame. I looked at the pictures, then around the house again to see if I’d missed anything—an article of clothing, a pair of shoes—that might suggest a woman was also living there. But I saw nothing.

Görbe came into the room carrying two huge snifters filled with Crimean Cup à la Marmora, his belly brushing the doorframe as he squeezed through with a scraping of shirt buttons. “What’re you looking at?” He stopped when I pointed to the pictures of his wife. “Zella,” Görbe said, adding nothing more, just standing there, drinks in hand. I asked where she was. “Zella is away,” came his quiet response. “In a better place.” This seemed to break him out of his trance and he handed me a drink and changed the subject.

Whenever Görbe spoke about his work there was a complete absence of the technical or practical aspects of publishing. Just as when he read to my sons, he spoke as if he was a privileged reader rather than the author. He was never sure, he said, where the story was going even as his writing and drawing proceeded, always one step ahead of his conscious intentions. This was the real Görbe, I always thought, not the clown at the bar and readings, but the guy who, when he talked of his work, seemed eased of all the flesh he carried, his need to filter the world through a cigar, his overindulgence with booze and food. The real Görbe grew excited talking of clouds hollowed out by sparrows, of fire escapes woven out of iron roses growing miles into the air, of bricks made of compacted song turned into choruses conducted with wrecking balls. I’d seen him like that with my kids, and guessed that when he went on tours to the tiny libraries of Idaho and Arkansas and Nebraska he was like that too—naive, filled with wonder, released from the persona he climbed into, like some fat suit, every morning in Queens.

“You like my kids, huh?” I asked one night as we stood on the balcony of the apartment I’d been renting, subsidized by NYU, on the fourteenth floor with a view of the Empire State Building and its coloured lights. But Görbe just sucked his cigar and looked at me as if the question was a trap he wasn’t going to walk into. I scratched the back of my head. “Well, you see, it’s just that I was . . . Well, it’s weird that you’d be so friendly to me just because fifty years ago you dated my aunt. A celebrity like you.”

Görbe looked at me then as if he wanted to throw me over the balcony. “The reason I’m so friendly,” he growled, “is because you’re such an asshole.”

I looked at him and tried to laugh.

“You’re bumping your head on the glass ceiling of your mediocrity. And you’re wide awake to it—why your agent doesn’t return your emails; why the writers at NYU show no interest in you; why New York leaves you cold. Most people can look away from that, dream up excuses—‘Oh, my agent is just busy’; ‘Oh, the writers at NYU are all self-important dickheads’; ‘Oh, New York is so superficial’—but not you, right? You know better than anyone you’re not going to make it, and you can’t hide it from yourself.”

I think I spluttered. I had no idea how to respond. And then, in a moment I’ll never forget, Görbe reached for my hand. It was the weirdest gesture. I tried to pull back from it, but the touch was so lonely, so childlike, it seemed more for his sake than mine, and when I gave in to it Görbe seemed to shrink, to fall into himself, clinging to me in the Manhattan night with the cavernous streets below, snow drifting past. For some reason I felt the need to say something reassuring to Görbe, to whisper him an apology for the world—“Everything will be fine, you’ll see”—when in fact it should have been him apologizing to me.

It was partly because of that conversation, but mainly because of my curiosity about Zella, that the next morning I went into the archives at NYU—combing through old copies of the Times, Observer, and even the Post—to piece together Görbe’s story. My aunt said he’d been a prominent children’s author during the communist era, as far as prominence went in those days, and he’d certainly had no trouble, as far as she or any of their mutual acquaintances could say, with the Soviet authority. “In fact,” she admitted, “he helped me out with his connections when I needed it.” As for his books, she said they “were like a utopia.” The children in them wanted to stay inside a dream, to realize a better world, and the communists liked that. “The kids were the proletariat,” she wrote, “at least according to the communist reviewers.” The waking world was the world as it is; and dream was the world as it could be. It was a pretty simple-minded interpretation, like most of them, but it saved Görbe. In other words, he had a good life under the Party—made enough money, had a nice apartment, ate and drank well. So nobody was really sure why he left. “As for his wife,” my aunt’s letter said, “I met her only once. She was just like Görbe except worse—dreamy, childish, never comfortable among adults. In fact, what seemed good in him seemed somehow bad in her. But maybe I was just jealous.”

There was almost nothing in the archives about Zella. For all the publicity given Görbe—starting with his defection from Hungary, played up relentlessly in the press, and by Görbe himself as an “escape towards the dream” (so much for the communist utopia)—there was only one article that dealt at all with his wife. Sure, there was a mention here or there, a comment about them having better “food and medical care and lifestyles” in the U.S., and a statement by Görbe saying his “private life” was “private” when asked in the early 1970s about how he and Zella were adjusting to New York. But that was pretty much it. There was nothing about their home life (not even one of those lousy spreads, so common with children’s authors, where some reporter visits them at home to prove that he really is a joyous family man with kids and a wife and colourful wallpaper and a house filled with constant storytelling); nothing about his career from “her” point of view (one of those pieces where the wife comments on her husband’s zany writing process, his odd schedules, his fun-loving ways with the kids in the park); in fact nothing about Görbe having a wife or any home life at all. Zella’s public appearances, rare in any case, stopped entirely after 1975, as did any mention of her on Görbe’s part. His entire persona was public, and, as such, especially after days and days of reading about it, totally put on, or so it seemed to me, for maximum publicity.

Most amazing were the pictures. My aunt had hinted at the transformation Görbe had undergone since the 1960s, but it was beyond what I’d expected. He’d been slight, almost pixyish, at the time of his arrival in New York, and what happened to him over the years was so extreme I could only think his metabolism had been damaged. There was no way you could get that fat in that short a time all by yourself. Part of the problem early on was that he hadn’t figured out how to dress for it. He was still wearing the clothes of a skinny man—narrow pants and tucked-in shirts—through much of the 1970s and ’80s. It wasn’t until the ’90s that he adopted the black suit and overcoat whose layers smoothed his folds and bumps of flab. It was why he took up the cigar as well—his features had sunk so far into the flesh of his face he needed something sticking out like that, a flag, to remind us he was still in there. And with the physical change came increasing accounts of bad behaviour—sarcasm, insults, fist fights. I was surprised so few articles commented on how a writer of such fantastical stories, of a world mapped out with such visionary innocence, did little more than satisfy his appetite for food, booze, tobacco and outrage. There was nothing beyond that, just the immensity of his cravings, as if Görbe had become the monster excluded from his books.

That, at least, seemed to be Zella’s opinion. The one article I did find on her was a page six piece from the New York Post, a single paragraph mostly taken up with the names of celebrities who’d attended a recent “bash” for one of Görbe’s books in 1975. They gave her three sentences: “It appears the booze was flowing pretty freely. Zella Görbe, the author’s wife, was acting ‘erratic,’ according to one guest. Before being escorted home by a private nurse, she regaled the room with stories of her husband’s weight, calling him a ‘fat disgusting pig’ one minute, then swooning over her ‘little boy’ the next.” There was nothing else, and however much I scanned through the information I’d gathered, returning to paragraphs and statements, there was no more about Zella’s “behaviour,” nothing to suggest she was a drunk, certainly nothing about a “private nurse,” though I did note a number of photographs where there was a third figure present—an older woman, dressed well but very straight, always in the background near Zella. Since none of the photographs listed her among the guests, either the newspapers didn’t know her name or she wanted it kept out. She looked stern, a mother figure, and the pictures made me recall what my aunt had said about Görbe when he was twenty years old: still afraid of the dark, playing hide-and-seek, climbing into the attic as if it was the entrance to a palace.

During that last month I kept my research hidden from Görbe. I worried about how he’d react. But Görbe must have sensed something, because he paid more attention to me than before, coming over unannounced with presents for the kids, sitting by the kitchen table (as much of him as would fit, anyhow) complimenting Marcy’s cooking and listening to her talk half-jokingly about how I couldn’t enjoy New York because I was so wrapped up in making contacts here, so obsessed with publishing in the right places, so distraught at not getting on, that the kids had started jumping on my back while I sat at the computer just to get some attention. “Ah, ambition,” Görbe muttered. “Toxic as poison.”

He even showed up to two dismal readings arranged by my U.S. publisher.

“Well, that sucked,” he said, afterwards. “It’s interesting that the woman in the audience—or I guess I should just say ‘the audience,’ period—didn’t even bother to buy a book. With all our eyes on her you think she’d have the decency.”

“The only thing worse than giving a reading is having to attend one,” I replied.

“Absolutely,” said Görbe. “You note that I never read myself. I just get up there and bullshit for a while. It’s all they want to hear anyhow.”

“More of your bullshit.”

“Right. More of my bullshit.” He laughed and blew a big cloud of cigar smoke. “You should think about that some time.”

“It doesn’t matter,” I said. “I read, I don’t read, it’s all the same.”

“That’s the spirit!”

It was, I think, the only way he knew to cheer me up, though of course I didn’t need to be cheered up. My failures were something I’d accepted, or at least stopped trying to avoid or explain. And that was the problem: the more Görbe came to my readings, or said he liked my book, or tried to get me to not take it so seriously, the more tiresome it became. I had become his foil, the failure against which he could measure his success, the person he might have been had he not so successfully managed his public persona and with it his career. Time would prove me wrong, of course—that is, I was Görbe’s foil, but not in the way I thought—but during those weeks I was irritated by his condescension, and one night, at two in the morning, after we’d consumed more Brandy Sangarees than advisable, I turned to Görbe and said, “How’s your wife?”

“My wife?” Görbe turned with the cocktail lifted partway to his lips. “My wife is none of your goddamn business.”

“Oh, I see,” I said. “You’re the only one who’s allowed to get personal.” Görbe said nothing, but I could see he was ready to hit me. I felt tears come to my eyes, not because of the implied violence, but for exactly the opposite reason, for the effort Görbe had been making, in his own way, to make me see what was important, and instead of which I was trying to get to him, to bring him down to my level, which was also a way of raising myself to his. “Why are you doing this? Why are you trying so hard with me?” I pressed my face closer to his, not caring what he did. “When I called you I thought we’d meet for coffee and you’d give me the usual bullshit about writing and living in Manhattan, and I’d give you the usual bullshit about how honoured I feel to be here, and we’d never see each other again.”

He grabbed my shirt and lifted me off the bar stool and slammed me against the bar—it felt as if my spine had snapped—then hauled me out of the room so fast my feet couldn’t keep up, and dumped me on the sidewalk out front. Then he went back inside.

I don’t know how long I stayed there, blind with humiliation. The feeling was so intense it somehow rebounded on itself and made me shameless, sitting on the pavement not caring who saw me, my clothes soaking up the slush, indifferent to Görbe’s voice back in the bar telling everyone how lucky I was. I got home and Marcy asked why I was wet, and I couldn’t look at her, and I couldn’t look in on Henry and Benjamin asleep in their beds. I was so consumed by what Görbe had done I couldn’t focus on anything.

The next morning Görbe left his apartment at ten, hopping the subway into Manhattan and then the M35 bus to Ward’s Island. He was dressed as always—black suit, black tie, the overcoat, the cigar. He wasn’t reading anything, wasn’t looking around, wasn’t muttering more than a quick hello to the bus driver. He took a seat and stared straight ahead, and once in a while he’d open a big sketchbook on his lap and make a note or doodle a picture for the next installment of the Atlas.

The morning started with snow, by noon it was rain, and I got off a block after he did to avoid suspicion and got soaked running back to catch Görbe checking in with the receptionist and moving down one of the corridors of the Manhattan Psychiatric Center. After he was gone, I went up to the receptionist and said I was there to visit Zella Görbe. She looked at me a bit, wanting to say something, but in the end kept it to herself. “Her husband just checked in, too,” she muttered.

I crept down the corridor after him, hoping not to be seen, and when I came to Zella’s room I skirted it and then snuck back and peeked in the window.

He was sitting in what seemed an absurdly small chair, all that weight on those spindly chrome legs, his coat hitting the floor in folds around his ankles.

The woman in the bed looked as if she’d been there all her life. But for some reason—maybe because she’d been there so long, removed from the stresses of lived life, taxes and sick kids and getting to work on time—Zella looked radiant, her face smooth of wrinkles, her skin white, her hair carefully arranged, to the point where I wouldn’t have been surprised to find that someone came around every morning to clean her up. As I peeked in further I saw the woman from the photographs, the one always in the background, aged so much I wouldn’t have recognized her except I knew she’d be there—the private nurse Görbe had been paying for who knows how long to look after Zella. For a second it seemed to me that the nurse, with her thinning hair and withered face and bent back, was somehow paying the price, physically, for Zella’s radiance. Closing my eyes I leaned against the wall and listened to her and Görbe. They were speaking Hungarian. It was the first time I’d heard Görbe use the language. The nurse’s name was Zsuzsa, and what they spoke of was Zella’s condition, how often the orderlies shifted her body to prevent bedsores, whether there was anything Görbe needed (“No” was his reply, though he thanked Zsuzsa for her concern), how his next book was coming along (“On time as always,” was his tired reply), and whether Zsuzsa needed anything (“You’ve looked after me just fine,” said the old woman). Then, after a short pause in which both of them seemed to be avoiding the next topic, Zsuzsa asked Görbe if he’d reconsidered “the treatment” proposed by “Dr. Norris.” He replied so loudly I heard every word: “I’ve told you, I’m not ever going to agree to that. It’s too risky.” Zsuzsa’s silence made it plain just how much she disagreed, or how little she believed that the “risk” was for him the only, or even the main, consideration.

“Can I help you, sir?” I was startled out of my eavesdropping by a nurse. I opened my eyes to find her standing in front of me, her hand on my shoulder as if she was worried I’d fall down. “Are you okay?”

“Oh,” I said. “I’m just tired. A bit dizzy.”

“Come over here.” She did as I’d hoped and led me away from Zella’s room to another waiting area, returning a second later with a glass of water.

“I was on my way to see Dr. Norris,” I said.

“Oh, he’s not in today,” said the nurse. “Did you have an appointment?”

“Well, no . . . I’m a writer. A journalist. I heard he’s been experimenting with some new treatment and I was thinking maybe there was a story in it.”

She looked at me strangely. “Well, I’m sure I wouldn’t know anything about that.” She got up and smoothed the fabric of her uniform on either hip, and said, “I hope you’re feeling better.” I told her I was, and the minute she was gone I rose to leave as well.

It didn’t take me long to look up Dr. Norris and discover he was a research physician at the Manhattan Psychiatric Center working on an experimental procedure for patients with “severe catatonia resulting from schizophrenia.” I didn’t have a lot of use for the article—it was filled with technical jargon I didn’t understand—except it gave me the window onto Görbe I’d been looking for. Zella was schizophrenic, the disease had worsened over time, and the reason Görbe lived in such poverty was because he spent all of his money on her care, and it didn’t matter to him, because without Zella there was no life for him worth spending money on. I sat in the Bobst Library with the research in front of me and wondered what I was doing, how I’d come to this, obsessing over the troubles of a man who’d gone through more suffering than I could conceive, and beside which my own failures in New York amounted to nothing. I wondered, too, why Görbe had not taken up Dr. Norris’s offer, for it seemed to me that neither he nor Zella had anything to lose. I’d seen her on the bed, so vegetative that whatever position they moved her body into it stayed there, like a mannequin. Even death seemed better than that. So why didn’t he agree to it? And I think it was this, the hopelessness of Görbe’s situation, his inability to do what he knew he had to do, that made me get up and call him.

We met in a Cuban diner, Margon, on Forty-sixth Street near Times Square. It was the dirtiest place I’d ever gone to in New York, but the food was the best, and Görbe was already into his third plate by the time I arrived. He watched suspiciously as I made my way along the narrow space between the tables and the people lined up by the counter. I’d told him over the phone I really wanted to “clear the air” over what happened at Lotus, my voice edging into an apology when he just coughed nervously into the phone and said, “Forget it, it’s nothing, come have lunch at Margon.”

“How’s your back?” he asked, and it took me a second to realize he was referring to slamming me against the bar. I shrugged, dropped my coat, got my food, and came back just as the waitress, who knew Görbe personally, was bringing him his fourth plate.

I waited until we finished eating, talking in the meantime about nothing—the business of writing, the stories we were working on—before asking, “How’s Zella?”

Görbe looked like he wanted to jump the table and grab my throat. But he was too fat, and was hemmed in by the people behind and beside him. In fact, the only way he could stand up was to upend the table, along with the food of everyone sitting there.

“I know about Dr. Norris,” I said, “and the terrible decision you have to make . . .”

But it was coming out all wrong, even to my ears. It occurred to me then, staring into Görbe’s enraged face, that I had no idea why I’d come here. I had thought, sitting in the library and the subway on the way up, that knowing what I knew would show Görbe I sympathized with him, and maybe I’d finally break through the front he put up, maybe he’d find in me someone he could talk to. But I wasn’t really there for Görbe.

“You shut your fucking mouth,” he said, pushing his chair back, bumping the man behind, who fell into his food and turned intending to say something but stopped when he saw how huge and mean Görbe was. “You don’t know anything about Zella.”

I slid out of my seat and stood across the table out of reach. “You’re just like me,” I said. In that moment it dawned on me why he didn’t seek out Dr. Norris, why he didn’t want Zella to wake up. “You’re nowhere,” I said, more to myself than him.

I left the table and went into the street. Görbe tried to get at me through the crowd but I was too fast, and he followed for only a few blocks before giving up, stopping on the edge of the crosswalk outside Toys “R” Us looking after me as I paused on the stairs to the subway. “You don’t want her to wake up!” I yelled, though it’s unlikely he heard me over the honking of horns, the roar of music, the shouts of Times Square. “You want her to sleep forever so she won’t see what you’ve had to become!” But it was obvious Görbe wasn’t listening to me. His gaze had gone beyond that, beyond whatever I might have been saying, all those unhappy truths, beyond even Hungary itself, where he’d been young once, and happy, and with Zella. For that was the person she would have looked for had she awakened—the self Görbe had left behind in the effort to get her here, to the best doctors and medicine, the best chance at recovery, doing whatever he could to foot the bills even if it meant turning himself into a monster she’d never have recognized. He was invisible in the eyes of the only person he cared about. Like me, he was a zero.

But I was wrong about that. Though it wasn’t until the following year, in the bookstore with Benjamin, that I realized it. I had thought that Görbe, like me, was trapped in a world of failure, and we’d found each other, two men without any illusions. Except of course I was full of them, for I had at home what Görbe would never have, only I didn’t know it, didn’t treasure it enough, and I think this recognition was what he’d been expecting from me during our time in New York, as if his tough talk and violence could jolt me into awareness. Instead, I had gone to Margon to extend my affection—to show the monster he wasn’t alone in his world—only to find that I was the monster, the only one, without the slightest clue to what affection really was.