Читать книгу Siege 13 - Tamas Dobozy - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

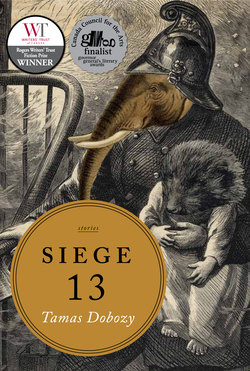

ОглавлениеThe Animals of the Budapest Zoo, 1944–1945

T WAS Sándor who finally posed the question in November of 1944, when it was clear the Red Army would take Budapest from the Arrow-Cross and the Nazis. “If there’s a siege, how are we going to protect the animals?” he asked, looking from one face to the next, totally baffled by the fact that everyone seemed far more interested in how they were going to protect themselves. “We’re going to have to work double hard,” replied Oszkár Teleki, director of the zoo, though Teleki was the first to run off that December when the Russian tanks entered the squares and boulevards, telling his secretary he was going to meet with the Red Army and insist that they respect the animals, and then asking her to pack all of the zoo’s money into a bag, just in case.

Sándor and József were the last to see Teleki leave, intercepting him near the exit and asking whether he had plans in place for the aquarium, where even now the attendants were working around the clock to keep the water from freezing by stirring it with paddles. Both men were suspicious because Teleki was wearing an overcoat belted at the waist, an elegant hat, and was carrying an ivory-handled umbrella in one hand and a suitcase bulging with money in the other, banknotes fluttering from every crack. As well, Teleki wasn’t taking the eastern exit out of the zoo—as he normally did when going home—but the western one, in the direction of Buda, of Germany, and away from the advancing Soviets.

“We should feed you to the lion,” said Sándor, to which Teleki responded by fingering his collar, looking nervous, and telling them he’d be back “really quite soon.” “You’re not going anywhere,” said József, and he grabbed hold of Teleki as he was turning from them, jerking him so hard the old man’s knees gave out and József had to hold him up above the muddy cobblestones.

József was about to do something else to him then—hit him, or pull the suitcase from his grip—but when he saw Teleki’s face—the bared teeth, the eyes darting back and forth, the desperation to escape—looking just like the animals did whenever there was an air raid, explosion of shells, the rattle of gunfire, flames shooting over the palisades, he let him go, knowing that the money would soon have as little currency as a fascist arm band. But if he’d looked a little closer he might have caught something else in Teleki’s face, the city’s future in its wrinkles and lines, a vision of what the next hundred days would be like, when Budapest’s populace would be driven to looting and stealing and scavenging and murder—and there would be much of that, down by the banks of the Danube where the Arrow-Cross executed the Jewish men, women, and children after marching them naked through the snow from the ghetto; or Széll Kálmán Square after the failure of Hungarian and German soldiers to break through the Soviet encirclement, bodies piled in doorways and cellar stairs and in other piles of bodies in an attempt to shield themselves from the rockets and snipers and tanks the Red Army had stationed along the routes they knew they would take—when the dead, whether half buried in ice, the muck of the river, or the frost that settled on them from their last laboured breaths, would speak to Sándor, and Sándor would in turn relay their message to József, the thing he was more and more obsessed with as the nights of the siege dragged on, the metamorphosis at work all around them. In the early days, when József was still alert, still sane enough to ask him what the hell he was talking about, Sándor muttered about human beings turning into “flowers and animals,” and held up Ovid, or some other book he’d stolen from the abandoned library in Teleki’s office, and whistled quietly, reading quietly, until József fell back asleep.

It got so bad that József would need that whistling to sleep, and when it stopped, late at night, and József snapped awake, more often than not he found that Sándor wasn’t there. He’d gone into the night, or disappeared, expending himself as if to prove that becoming nothing could be a transformation too. Though he was always back by morning with his dirty nails and oily face and tattered clothes and the look of someone who’d lost himself along the way.

But before all that, December turned into January. Unlike many of the other attendants, Sándor and József did not have families, and so they saw no reason to go home from the zoo except to risk dying in the streets, or being bombed out of their tiny apartments, or starving to death in the cellars that had been converted into bomb shelters. When the zebras were found slaughtered in their pens, large strips of meat carved hastily from their shoulders and flanks and bellies no doubt by starving citizens, the two men fed what was left to the lion and moved into the vacated stalls, Sándor ranting about how the zebras should still be alive and it was the looters who should have been fed to the lion.

When Márti, another of the attendants, was shot in late January as she was trying to tear up a bit of grass for the giraffe in the nearby Városliget, and somehow managed to stumble back to the zoo, she described in a sleepy voice what she had seen out there in the city. Sándor tried to get her to be quiet, to rest, pulling the blanket to her chin, but she kept speaking of the shapes of flame as a child might speak of clouds, seeing in them animals dead or dying, their souls somehow escaping the bodies trapped in the zoo, transmigrated into fire, taking revenge on the city. She said it was burning, all of it—the Western Station, the mansions along Andrássy Boulevard, the trees in the park like used matchsticks. She’d seen a street where blue flame was dancing through every pothole and crack, playing around the rim of craters, the gas mains ruptured underneath, continuing to bleed. “It was like a celebration,” said Márti, before closing her eyes and falling into a sleep neither József nor Sándor tried waking her from.

The night after she died, they climbed the roof of the palm garden, which gave them a view beyond the palisades toward where the fighting was going on, now far to the west, mortars and tanks and bullets pounding the lower battlements of Buda castle, flashes of white light whenever the smoke cleared. The sky held odd things—crates falling by parachute onto the ice over the Danube; gliders crashing at night, guided by spotlights into trees and buildings; ash rising like a million flies.

Sándor tried to keep reading during those days, scrambling up a ladder to Teleki’s library after the air raid destroyed the staircase, as if the books were more than a distraction, as if they were necessary to hurry his mind along, as if it was possible to stop thinking by thinking too much, by exploding thought, at a time when having a mind was, more often than not, a handicap. Of the two of them he’d always been the one given to dreams, and as they sat on the roof of the palm garden that night, Sándor spoke to József of what he’d discovered in Teleki’s office, an entire library, books ancient and modern, devoted to the subject of animals—“I had no idea Teleki was such an intellectual,” growled Sándor above the crackling of guns—and then began to speak of how characters in myths and stories and fairy tales turned into horses and flowers and hounds and back again, or into other people entirely, crossing limits as if they didn’t exist, becoming something else. “But now, I mean now”—he waved his arms around as if he could encompass the last five centuries—“now we don’t transform. We’re individuals now. Selves. Fixed in place.”

“Well,” said József, turning over Sándor’s ideas, “what difference does it make? They died in wars just like us.”

“Maybe that’s how they explained death,” said Sándor, his face glazed with the light of nearby fires. “Becoming something else.” He gazed down through the glass roof of the palm house. “Anyhow, we’re not dead yet,” he purred, flexing his fingers, József thought, as if they could become claws.

“But did they stay themselves, I mean, when they became something else?”

“That’s just it. There was no self to begin with. Just an endless transformation, a constant becoming.”

“So then a lion was worth the same as a human being.”

“Well, I don’t know about ‘worth,’” said Sándor, smiling at József. “But there wasn’t the same way of telling the differ . . .”

But before Sándor could take the idea any further, he was already crashing through the roof of the palm garden as the shell exploded, disappearing into the fire and shock waves and rain of glass, while József was able to scramble down before the next mortar fell whistling into the hole the last one had made, scrambling down, and then through the cracked doors of the glass building, shards raining all around, the alligators and hippos of the central exhibit too shocked to snap or charge at him, lifting Sándor’s body from where it lay face down in a pool of water, and smiling despite himself when his friend began spluttering, bruises spreading across his face. Two days later, the alligators died, frozen stiff in their iceencrusted jungle, though the hippos lived on, drawn to the very back of the tank, where the artesian well kept pumping out its thermal waters, the fat on their stomachs and backs thinning away as it fed them, all three growing skinnier and skinnier in the steam.

Later, when Lieutenant-General Zamertsev questioned József about the lion, trying to get him to reveal where it was hiding, József resisted by speaking instead about the alligators and hippos, about the destruction of the palm garden as the moment when Sándor and he realized they would have to “liberate” as many of the animals as they could. Zamertsev looked at him, and then turned to the Hungarian interpreter and whispered something, and then the interpreter said to József, “You actually thought it was a good idea to let the lions and panthers and cougars and wolves roam free?”

József knew that Zamertsev didn’t believe him, that he was not accusing him of excessive sentimentality so much as lying, or maybe outright craziness, as if between the destruction of the siege and Sándor’s ranting, József’s brain had also become unhinged. Zamertsev was right in a sense, because it wasn’t what happened to the alligators that made Sándor and József wander around the zoo unlocking cages, but rather the arrival of the Soviet soldiers, Zamertsev’s men, high atop their horses, demanding that they first release a wolf, then a leopard, and then a tiger, all so they could hunt them, these half-starved creatures that could barely walk never mind run, chasing them down with fresh horses and military ordnance, drunk and laughing and twice crazy with what the war had both taken from and permitted them.

The attendants were into the champagne that night, having discovered a crate of the expensive stuff in one of the locked trunks Teleki left in his office, along with several sealed tins of caviar and a box of excellent cigars. Sándor handed out bottles and tins and matches to József and Gergő and Zsuzsi, all of them so hungry and tired of thinking about what might happen to them the following week, or tomorrow, or the next minute that they popped the corks as fast as possible and began drinking, trying to wash from themselves the cold and fear and the dead animals all around, as if by concentrating you could keep only to the taste of what was on your tongue, and think of nothing else.

It was of course Sándor’s idea, the action he decided on after he’d drained his second bottle of Törley’s, leaving off the caviar, looking at everyone’s grubby knuckles, their wincing with the sound of another explosion or rattle of gunfire or the slow fall of flares (falling so crookedly they seemed to be welding fractures in the sky). And so it was neither love nor logic that led them around the zoo that night but drunkenness, jingling keys pulled from Teleki’s walls, moving past the carcasses in the monkey house, many of them frozen to the bars they’d been gripping when their heat gave out and they laid their heads onto their shoulders welcoming the last warmth of sleep; or in the tropical aviary, the brightly coloured feathers gone dull on the curled forms, their heads dusted with frost and tangled in the netting overhead, as close as they would ever again come to the sun; or in the aquarium, where someone now gone, perhaps Márti, had broken through the glass of the tanks and tried to chip some of the fish out of the ice, whether in some pathetic attempt to thaw them back to life or to eat them no one could guess. In the end, it was less an organized act than a celebration, less motivated by reason or a goal than a delight in the moment when the cage swung open and something else bounded or crawled or slithered or flew out, the four of them downing champagne and running around, eagerly seeking the next thrill of release, opening after opening, an orgy of smashing those locks they’d worried over for years. And when it was over, when there wasn’t a single cage left to open, an animal to free, then Gergő and Zsuzsi freed themselves, waltzing out the front gate straight into a warning shout, a halting laugh, a hail of machine-gun fire.

Which brought József and Sándor back to themselves in a hurry. “I’ll bet it did,” said Zamertsev, leaning over the table and staring at József, the shoulders and chest of his uniform covered with red stars and hammers and sickles and decorative ribbons. “And I guess that’s when you got the idea of feeding my soldiers to the lion.”

“It was your soldiers’ horses we wanted,” mumbled József, still so amazed by the last sound Sándor had made—he could imagine him tossing his head and baring his teeth and roaring so loudly it could be heard above the guns—that József might have been speaking to anybody, treating Zamertsev as though he was an acquaintance he’d met in a restaurant or café rather than someone who at any moment could have sent him out to be shot. “A lion can live a lot longer on a horse than a man, you know.”

But the truth was, he wasn’t so sure, for Sándor had frequently looked down upon the Russian soldiers (both from the roof of the palm garden, and later from the palisades) and licked his dry lips and recalled the Siege of Leningrad, wondering if people in Budapest would end up eating human flesh, as they were rumoured to have done there. At the time, József had not connected Sándor’s actions with appetite, but with a hatred of the Soviets, because with all the dead German and Arrow-Cross soldiers not to mention civilians lying in the streets, perfectly preserved by a winter so cold even the Danube had frozen over, there was no need to hunt the living. Sándor had made strange references to the Soviets and the Red Army as the two of them wandered around the zoo in the waning days of the siege, when most of the fires in Pest had gone out and the Russians were mopping up what was left of the enemy by marching Hungarian men and women in front of them through the streets and forcing them to call out, “Don’t shoot, don’t shoot, we’re Hungarians, give yourselves up”; though to the west the fighting was still thick, relentless, out there across the Danube, on the Buda side of the city, where the Nazis and Arrow-Cross were holed up on Castle Hill, surrounded, running out of ammunition and food, dreaming of a breakout.

Of the animals they’d released, a few vultures and eagles remained, circling above the zoo and drifting down lazily to feed on the plentiful carrion in the streets. When they returned to their nests, Sándor would wonder what was more poisonous in their bellies, the flesh of communists or fascists. He would say things like that. They held discussions, long into the night, and József said the fascists were wrong to speak of their beliefs, the society they envisaged, as natural, for no animal was ever interested in war for glory, or compiling lists of atrocities, or mastering the world, or getting rid, en masse, of another species, and that more often than not what animals did was tend only to their immediate needs, and in doing so created a kind of harmony . . . “Harmony?” laughed Sándor. “You sound like a communist!” And he spoke of how a male grizzly will kill the cubs belonging to another male so that the female will mate with him; how he’d once heard about a weasel that came into a yard and killed twenty-five chickens, biting them through the neck, without taking a single one of the corpses to eat; how certain gulls will steal eggs from others, sit on them until they hatch, and then feed the chicks to their own young; how a cat will play with whatever it catches, torturing it slowly to death, all out of amusement. “Does that sound like harmony to you?” he asked József.

Zamertsev looked a moment at József, who sat there trembling in the creaking chair in the headquarters the Red Army had put up in one of the half-obliterated mansions along Andrássy Boulevard, still dressed in the ragged attendants’ uniform, unwashed these hundred days, his hair matted and filthy, so shrivelled by hunger Zamertsev thought he could see the man’s spine poking through the skin of a belly fallen in on its emptiness. Then Zamertsev came around the desk and grabbed József’s chin roughly in one hand and said, “I’m not interested in what you think I want to hear. Politics. . . .” He glanced at the interpreter, who raised his eyebrows. “I want to protect my . . . the people’s army . . . which means telling me about Sándor, what he did, what I’m dealing with . . .”

Protect the people’s army. József wanted to laugh. If your soldiers had been kept in check, if they hadn’t come in wanting a safari all their own, we wouldn’t have had to free the animals in the first place. After that, Sándor seemed intent on prowling around the zoo as if he was an animal himself, even though József warned him to stay inside, because there wasn’t a day when one of the carnivores that was still alive didn’t come upon another, the polar bear devouring the wolves, the wolves taking apart the panther, the lion emerging at night. But that’s how it was then: József working hard to conserve himself, to survive, while Sándor had given up on everything—first sleep, then food, then safety—divesting himself of every resource.

Somehow Sándor had gotten word to the Russians that the lion was living in the tunnels of the subway, and when the other predators were gone—having finally eaten one other, or been shot, or wandered off—then the lion took to eating stray horses. Sándor would point out its victims to József when they went out to gather snow for drinking water, Sándor hobbling along, weakened enough by then to need the help of one of Teleki’s canes, though he still had enough presence of mind to show József how it was teeth not ordnance that had made the gaping holes along the flanks and backs and bellies of the horses. “The lion must be weakened,” said Sándor, clutching himself, “otherwise, it would have dragged the carcass away to where it lives, and eaten the whole thing.”

“Or maybe it’s too full to bother,” said József, envious of its teeth.

At night, József would awaken and not even turn toward Sándor’s pallet, because he knew he wasn’t there. Night after night he’d awaken and Sándor would be out. Sleepwalking is what József thought at first, but when he asked about it, Sándor would laugh and say he’d been out “getting horses.” There wasn’t a lot to what Sándor said anymore, though truth to tell József himself was having trouble coming up with anything to say, and of saying it, when he did, in a meaningful way.

“My soldiers tell me Sándor was meeting with them,” said Zamertsev. “That he was arranging lion hunts in the subway tunnels.”

“You could fit a herd of horses in there,” nodded József. “But it was very dark. And the soldiers were always drunk. And there were bullets flying all over the place.”

“It was one way to feed the lion,” said Zamertsev. “You knew about it. Perhaps even helped him?”

No, József shook his head, and then a second later, he nodded yes, and then stopped, not knowing who or what he’d helped, deciding that it certainly wasn’t Sándor. Zamertsev was wrong to think that Sándor was feeding the lion, for that’s what József had thought at first as well, as if the lion and Sándor were two separate things. But it was better that Zamertsev think this than what József knew to be the truth, the transformation he’d witnessed the day he’d carried Sándor to the subway entrance, one of the few that wasn’t bombed out or buried in rubble or so marked by the lion’s presence that even humans could sense the danger there. He’d pressed his body against the door—it was an old service entrance used by the engineers and subway personnel, wide enough to fit a small car, covered with a corrugated metal door—envisioning that awful metamorphosis.

As it turned out Zamertsev wasn’t like the other soldiers, so easily led into the same trap. He sent for one of his men and told him to get a map of the old Franz Josef Underground Line, staring silently at József until the blueprints were delivered, at which point he spread them across the desk and began tracing the possible routes into and out of the subway, ignoring entirely the service entrance József had told him about. It was as if Zamertsev knew, József thought, as if he’d discerned the bits of the story he’d left out, and was even now being guided over the map by what József hadn’t told him about that last night, when Sándor had crawled over and whispered to him of the effort of getting horses for the lion, of how weak he’d become, though what József really heard in his voice was a hunger so great it would have swallowed him then and there if Sándor had had the strength, if he felt he could have overpowered his friend. “I can’t do it alone,” Sándor mumbled. “I can’t walk.” When József asked if their friendship no longer meant anything to him, Sándor rubbed the place in his skull where his cheeks had been and said something about “word getting around,” and the soldiers “staying away,” and then paused and smiled that terrible smile, lipless, all teeth. “It’s because I’m your friend that I’m asking you to do this. There is no greater thing a friend could do,” he said, laughing without a trace of happiness.

József had looked at him then, turning from where he’d been facing the wall, hugging himself as if in consolation for the emptiness of his stomach, for the delirium of this siege without end, the constant fear, the boredom, waiting on the clock, the slow erasure of affection, of the list of things he would not do. “The city is destroyed,” he said, not wanting to do as Sándor asked, not wanting even to address it, for he thought he’d caught another implication in his voice now, one even worse than what the words had at first suggested. “There are people dead and starving,” he continued, “the Soviets are looting, hunting, raping, and you’re worried about a lion. Fuck the lion,” said József, “fuck everything,” and he turned over on his pallet, lifting the layers of plastic sacks and tarpaulin they used for blankets. But Sándor nudged him again, and when József let out an exasperated moan and turned, he saw that his friend was already half transformed, the hair wild around his head and neck, his fingernails much longer than József’s, and dirtier too, packed underneath with the hide and flesh of horses and men and what else, reduced from malnourishment and injury and trauma to crawling around on all fours. “I need you,” growled Sándor, though he had lost so much by then that it came out like a cough, the cords in his throat too slack, or worn, for much noise, and it cost him to raise his voice above a whimper.

Need me? wondered József, rising from the sheets and drawing Sándor’s head to his chest. You don’t know what you need, he thought, as if there were two pulses beating in counter-rhythm within Sándor, two desires moving him in opposite directions. He held him like that for a while, feeling his friend’s eyelids blinking regularly against his skin, thinking of how Sándor had run out of the zoo after Gergő and Zsuzsi, trying to gather up their limp forms, of how often they’d found him squatting in the cage of this or that dead animal, as if by lifting a wing or an arm or a leg he might reanimate them, or, as József had once observed, actually put on the animal like a suit of clothes and become it, leaving his humanity behind. At the same time Sándor had been moving in the opposite direction, trying to keep in mind who he was, who he’d been, what he cared about.

“Listen, Sándor,” he murmured, frightened by what was taking place in his friend’s body, the spasms that passed through it as he held him. “You have to pull yourself together,” he said, “the siege won’t last forever.” But Sándor was already past the idea of waiting, József knew that, past thinking of what had happened and what was to come. What he really wanted, what he needed, had nothing to do with József at all, for József was already disappearing for Sándor—disintegrating into the state of war, falling apart with the capital and the zoo, with the death of the animals—and all Sándor needed to realize his own disappearance was this one last act, this final favour. But things weren’t like that for József, not yet, for the presence of Sándor was still keeping him intact, as if the strength of their friendship, the history they shared, whatever it was in his character that Sándor loved, could recall József to himself. He looked at Sándor and saw what the war had done to friendship after it had finished with everything else—with sympathy, with intelligence, with self-awareness, with loyalty and affection and love—all those impediments to survival, all those things that got in the way of forgetting who you were. It was for this that József envied Sándor, for Sándor had forgotten him just as he’d forgotten that the soldiers he’d fed to the lion were men, that the bodies the birds fed on where those of women and children, that there was even such a thing as his own life, or anyone else’s, and that it might be worth preserving.

When he finally rose up with Sándor that night, carrying him in his arms like a child, József wasn’t sure if he could do what Sándor wanted him to do, because he was still clinging to his friend’s memory, unwilling to let him go, as he would weeks later, even more so, after the conversation with Zamertsev, after the Soviet hunting party had gone out—sober this time, no horses—carrying flashlights and head-lamps, determined to do it right. He had set out that night in exactly the same way, out the door, moving along, bent with Sándor’s weight under arc lights and stuttering street lamps, dodging patrols that weren’t really patrols but an extension of the three days of free looting the commanders had granted their troops.

By then he knew what Sándor needed as much as Sándor did—this is what József would not tell Zamertsev—and when they arrived at the subway entrance and swung open the door and looked inside, József hesitated. And when Sándor, resting his head against his old friend’s chest, asked to be put down on the threshold, József laughed and said no, it was fine, they could go in together, it didn’t matter. “Please,” said Sándor, jerking limply in József’s arms. “You’ve been better with your grief,” he said, “better able to use it—to help make yourself stronger.” With this, József finally understood what Sándor wanted, and why, and József would remember it as the moment when he finally gave in to the siege, to its terrible logic, to what Sándor hoped to become, what he needed József to witness. He said goodbye before putting Sándor down and closing the door on him. Then there was only the weakness, from carrying his friend across the ravaged city, from using up what little strength was left in closing and slumping against the door, too tired now to pull it open, knowing he would have nightmares in the years to come—nightmares of banging on it, wrenching at the handle, calling out to Sándor—only to wake to the terror of loss, alone in the dark with all he’d been separated from, as if there was no way to figure out where he was, where he began and ended, until he realized what was out of reach. It was Sándor’s last gift, to József and the lion both, what he thought they needed to live, as if grief could work that way, though in the end it was only what he’d wanted: the death of whatever it was—affection, friendship, love—that kept him in place, reminding him of what he was and in that way of what he’d seen, when all he wanted by then was the roar and the leap—the moment when he was finally something else.