Читать книгу I Remember - Ich denke an ... - Tanya Josefowitz - Страница 10

ОглавлениеOn the day of arrival Mother again was simulating emotion rather than illness. Bundled into her coat, her collar high up, and a hanky covering her face, she feigned tears of joy. We got off the boat and were met by Diana, my cousin, and an even older cousin, Issi Glickin, who later became our private tutor and mentor. He taught us English, mathematics, history and everything concerning the American way of life. Needless to say, my Daddy and Aunt Mary were there as well.15 We cried, we laughed, we hugged and kissed each other and felt elated and relieved. And yet, I was bewildered and full of apprehension about the unknown and unfamiliar life that was expecting us.

We all took the train to East Orange, New Jersey, where Aunt Mary lived.16 This was to be our new home for the next month. It was evening, and Vladimir and I were not a bit tired – much too excited by all the new people, experiences and sights. I truly did not realize how ill my Mother was. She really was on her last breath. The doctor came, and cousin Diana who had taken leave of absence from her job for the next week, took care of my Mother day and night with inhalations, chicken soup, hot drinks and lots of love and devotion. Mother survived but only by the skin of her teeth. There was no penicillin as yet to cure her very severe pneumonia.

Vladimir and I were both overwhelmed with all the new experiences, delighted to be reunited with our Daddy, and to be spoiled by all the various cousins and their parents, our Aunty Mary and Uncle Max.

One of our main attractions was Uncle Max’s grocery store on the ground floor. It smelled of fresh ground coffee, smoked fish, hot pastrami and was full of the most fascinating items, from soap to nuts, to bubble gum and bagels, just to name a few. Our good-natured brilliant Uncle Max let us touch and taste everything in the shop.

Up the stairs on the first floor was my Aunt Mary, my father’s sister, who cuddled us into her big, soft bosom and spoke to us in Yiddish – which we could understand as it had a lot of similarity to German. We drank gallons of fresh orange juice and milk and our daily meal was chicken soup with vegetables. Then, we would run down to Uncle Max and he would cut us each a few slices of liverwurst and Salami which we devoured with gusto.

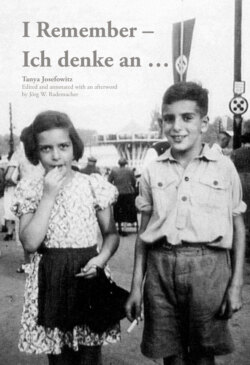

For a few weeks we were the center of attention. All our friends and family came to see the new arrivals – the refugees from Germany. We were often asked to sing our German songs and we obliged happily. To us children, it seemed a constant party. We met the neighboring children. There again, language posed no problem.

At first I was afraid of black people, never having seen any in Germany. But very soon many of my closest pals were black and many remained my friends throughout my life. Everything was new and different, the subway, skyscrapers, drug-stores and friendly cops. We took to American life like fish to water, and I was in seventh heaven.

I remember, when I was very young in Germany, we were told: “If you are naughty the policeman or the black man will get you!” Whatever that meant to me I don’t know, but it was a very scary threat.

Mother always claimed that it was my fantasy – that I had never been threatened by such words. Maybe so. There is one thing, however, I do remember. Several months after we came to the USA Mother was invited to lunch in Chinatown with friends. She took me with her, and as she was vastly in conversation, I wanted her attention and kept interrupting. She told me to be quiet or she’d give me a “Watschen”17, meaning a slap on the cheek, a commonly used way of imposing discipline in Germany at the time.18 But I said to her: “No, you don’t, or I will report you to the police.” You see, once in the USA, I was no longer afraid of the police. My whole life was changing so quickly.