Читать книгу I Remember - Ich denke an ... - Tanya Josefowitz - Страница 7

ОглавлениеWorms, where I was born and where we lived, was a small but beautiful old town1. My parents were quite well known there and everybody seemed to like them, including the officials of the city who would close an eye to the warm relationships they had with Christian friends. Many of my parents’ friends were not Jewish, and after Hitler’s rise to power they were not permitted to mingle with Jews. In spite of it, as food for Jewish people was rationed, my parents’ friends would secretly come at night with baskets full of eggs, cheese, meat, butter, etc. concealed under some cloth.

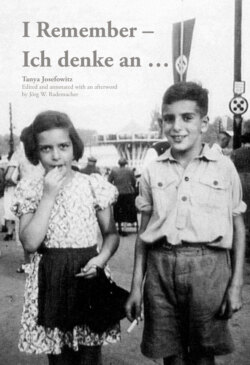

I remember the one particular crucial night when we had such visitors. It was around 9.30 in the evening in March 1938.2 My brother Vladimir and I were already in bed. He was nine and a half and I was eight years old. In the next room we heard the guests and parents laugh and talk in hushed voices. They seemed quite animated and full of fun. Outside, as usual, there was the click and clack of booted feet marching in unison along the cobblestone pavement under our nursery window.

The Gestapo always marched in groups, wearing high boots with metal tips and heels whose rhythmic sound could be heard all over town. Vladimir and I had gotten used to these sounds. But that night, when the loud steps came to a sudden halt outside our house and when the door bell hit us like a bolt, we sat up in bed, all ears, frozen and paralysed with fear.

The intimate, cheerful conversation in the sitting room had also come to a stop. I heard my parents open the front door and close it after a moment. Then the click clack in the street resumed its course and faded into the night. We peeked through the slit of our door and saw the friends gathered around my parents. They were all frantically busy, reading the letter that had just been delivered. Then everybody began to speak at the same time, and the ominous sound of their frightened voices made me fearful, as I strained to hear what was being said.

Mother realized our door was open and saw our little faces peeking through. She reassured us and tucked us into bed. But for a long time I couldn’t sleep, trying to understand what was going on, and feeling that a terrible message must have been in that letter. In the morning Mother explained to us that we had to leave Germany very quickly. There was great hustle and bustle in the house. Many friends came to help pack. There were phone calls all day long, and we were told to keep out of the way and to stay in our rooms. We felt totally confused and isolated, particularly when it turned out that Father had to depart in a great hurry, and that he was going far away.

The hand-delivered document was an official notice informing us that we, the whole family Kagan, being Russian Jews, were ordered to leave Germany within exactly ten days. If we did not comply and stayed even one additional day, we would be deported and put into a concentration camp.

During the First World War, Father had been taken a Russian prisoner in Germany. After the war he did not wish to return to Communist Russia. Though he kept his Russian citizenship, he was more than happy to remain in Germany where he had made many good friends. Thus he stayed on to work and to enjoy his freedom. When he met Hildi Wallach3, my beautiful mother, it was love at first sight.

They got married, had two children, and as he had retained his Russian citizenship, my German born mother and her children automatically had to become Russians as well. Ironically, this was now one of our saving graces. As Russian Jews we were forced to leave Germany and thus had a chance to save our lives.

At that time, I understood very little of what was happening. But I was terrified and full of apprehension even before the fatal night of our expulsion. Our gentle, cozy home had suddenly become a fearful place, and everything seemed to fall apart.

Two days after receiving the expulsion letter, my father left for Bremen where he was to catch the “Manhattan”, the very next boat for New York. In Bremen he was lodged by a Catholic friend, a silversmith, who escorted him to the boat, wished him well and sent him off with a bottle of brandy.

Father traveled on a visitor’s visa sent to him by his sister Mary who lived in New York. He had had it for several years and kept renewing it, as he could never tear himself away from his family. Now he was only too happy to use it, for he was convinced that once in the USA, he would be able to acquire visas for us all and to have us follow him. His departure left us feeling completely lost and in a total turmoil. All we were allowed to ship to our next destination was a large box – called a container – with some furniture and whatever we could squeeze into it. Friends, neighbors, Jews and non-Jews, all came to help us and so did my mother’s father who later on, with the assistance of friends in the Vatican, managed to escape to the United States with my step-grandmother.

We left Worms, our home, our friends, our past for a completely unknown future, and our first stop was in Munich to say good-bye to my grandmother. Vladimir and I stayed with our beloved granny Emma. It was the very last time we saw her. She was later deported and died in Theresienstadt.

We still needed visas for any country that would harbor us on our way to the United States. There were many disappointments. My grandfather, a prominent Munich citizen and former War Veteran, was very well to do with many connections in the outside world.

His efforts to get us visas were of no avail. Nor could my mother’s sister in Denmark or her brother in Spain be of any help. She was married to a Protestant and relative of a famous Danish writer and her brother’s wife was a Spanish Catholic. But all this did not open any doors.4

After all our possibilities seemed exhausted, my mother suddenly remembered some Jewish friends who with their family, a few years ago, had emigrated to France. She contacted them in Metz where they were living and luckily! – they were able to get us a two months’ visa to stay in France. This, however, was finalized on the very last and dreaded tenth day of our residence permit in Germany. If by then we had not left the country, we were to be deported to some concentration camp. We therefore had to leave immediately.

The container5 had been shipped to the USA, and all we had with us were three small suitcases and the equivalent of $200,00, the only money we were permitted to take out. With warm, hopeful send-offs and tears, yet much relieved, we finally took off after emotionally loaded good-byes at the station.

It was a cold, gray day in the middle of March 1938. Mother was 32 [in fact, 34] years old and though her heart was trembling, she showed great courage and put on a cheerful air for the sake of her two children. We left on the train to Saarbrücken, a border town6, where we were to catch our connecting train at 7.00 p.m. to Metz in France.