Читать книгу The Harmony Silk Factory - Tash Aw - Страница 12

7. Snow

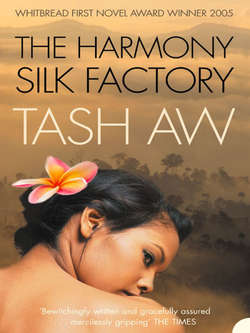

ОглавлениеMy mother, Snow Soong, was the most beautiful woman in the valley. Indeed, she was one of the most widely admired women in the country, capable of outshining any in Singapore or Penang or Kuala Lumpur. When she was born the midwives were astonished by the quality of her skin, the clarity and delicate translucence of it. They said that she reminded them of the finest Chinese porcelain. This remark was to be repeated many times throughout her too-brief life. People who met her – peasants and dignitaries alike – were struck by what they saw as a luminescent complexion. A visiting Chinese statesman once famously compared her appearance to a wine cup made for the Emperor Chenghua: flawless, unblemished and capable both of capturing and radiating the very essence of light. As if to accentuate the qualities of her skin, her hair was a deep and fathomless black, always brushed carefully and, unusually for her time, allowed to grow long and lustrous.

In company she was said to be at once aloof and engaging. Some people felt she was magisterial and cold, others said that to be bathed in the warm wash of her attention was like being reborn into a new world.

She was magical, compelling and full of love, and I have no memory of her.

She died on the day I was born, her body exhausted by the effort of giving me life. Her death certificate shows that she breathed her last breath a few hours after I breathed my first.

Johnny was not there to witness either of these events.

Her death was recorded simply, with little detail. ‘Internal Haemorrhaging’ is given as the official cause. Hospitals then were not run as they are today. Although many newspapers reported the passing of Snow Soong, wife of Businessman Johnny Lim and daughter of Scholar and Tin Magnate TK Soong, the reports are brief and unaccompanied by fanfare. They state only her age and place of death (‘22, Ipoh General Hospital’) and the birth of an as yet unnamed son. For someone as prominent as she was, this lack of detail is surprising. The only notable story concerning my birth (or Snow’s death) was that a nurse was dismissed on that day merely for not knowing who my father was. As Father was absent at the time, the poor nurse responsible for filling in my birth certificate had the misfortune to ask (quite reasonably, in my opinion) who the child’s father was. The doctor roared with shock and disgust, amazed at the nurse’s ignorance and rudeness. He could not believe that she did not know the story of Johnny Lim and Snow Soong.

Snow’s family was descended, on her father’s side, from a long line of scholars in the Imperial Chinese Court. Her grandfather came to these warm southern lands in the 1880s, not as one of the many would-be coolies but as a traveller, a historian and observer of foreign cultures. He wanted to see for himself the building of these new lands, the establishment of great communities of Chinese peoples away from the Motherland. He wanted to record this phenomenon in his own words. But like his poorer compatriots, he too began to feel drawn to the sultry, fruit-scented heat of the Malayan countryside, and so he stayed, acquiring a house and – more importantly – a wife who was the daughter of one of the richest of the new merchant class of Straits Chinese. This proved to be an inspired move. His new wife was thrilled to be married to a true Chinese gentleman, the only one in the Federated Malay States, it was said. He in turn was fascinated by her, this young nonya. To him she was a delicate and mysterious toy; she wore beautifully coloured clothes, red and pink and black, and adorned her hair with beads and long pins. She spoke with a strange accent, the same words yet a different language altogether. This alliance between ancient scholarship and uneducated money was a great success from the start, especially for Grandfather Soong (as he came to be known), who was rapidly running out of funds.

His talent for finding an appropriate partnership appears to have passed on to his son TK, who proved to be even more astute. While managing to cling on to his father’s scholarly heritage, TK also managed to learn the ways of the new Chinese – the ways of commerce and industry. He did so through his wife, Patti, who was the daughter of no less a person than the kapitan of Melaka’s right-hand man. TK and Patti were a formidable pairing indeed.

TK had always shown exceptional promise, even as a young boy. He passed his examinations in law at the University of Malaya with the highest honours and for a brief spell studied at Harvard before impatience, boredom and cold weather brought him home. For a while, he considered pursuing a career in banking in Singapore, but opted instead to return to the valley, where there were none of the distractions that abounded in Singapore – nightlife, foreign money, women. He was a notable calligrapher and painter, and his home was decorated with many scrolls of Tang poems, written in his own flowing hand. Many of them have been rehung in that old house, the same house which was Snow’s home and, briefly, Johnny’s too. The house is now inhabited by Patti’s relatives – my cousins, I suppose, though I do not know them.

Like me, TK was the only son of a wealthy family in an area where wealthy families were uncommon. People would have known and talked about him simply because of who he was, even before he had done anything of note. It is a difficult thing to live with. When you know that everyone talks about you behind your back, while looking at you with silent eyes, it can sometimes have an effect on you. For although people may admire your standing in life, they may also boil with jealousy and hatred. It makes you think differently from other people, and eventually it distorts your personality. That was the case with TK. A young man like him wearing smart Western clothing and spending his time painting would have aroused much comment. In the end, it was the burden of what other people said that made TK settle down and build a life and a family for himself, just as his father had before him.

First, he changed his appearance. He swapped his Western suits for the traditional Chinese clothes his father once wore, the attire of a Manchu civil servant – long shirts made of the richest brocade, trousers of plain, good silk. This kind of dress was no less conspicuous in rural Malaya, and many people thought it was merely a phase which he would soon leave behind. But he persisted with it to the end of his days; it is how he is dressed in the stiffly posed photographs that survive. He continued reading classical Chinese texts; he wrote and he painted. But his demeanour changed. Whereas before he had been flamboyant and easily excitable, now he was serious and calmly spoken. At last, sighed his parents, he took an interest in business. He benefited from family connections and became involved in large-scale enterprises such as commercial loan-making and the import and export of tin and rubber to Europe. He got married too.

Patti was said to have been a woman of notable beauty, although to my eyes hers must have been a beauty of that particular age. Certainly, the worn sepia-tinted portraits do not do any of their subjects justice, but even so, she appears sullen and withdrawn. If you look closely, you can see where Snow inherited the cold streak that she was said to have possessed. Patti’s mouth is drawn tight and thin, her eyes hard and dark. Her looks are not dissimilar to her daughter’s but her beauty (if it is beauty) is of a harsher variety.

Though I close my eyes and search my memory I cannot recall ever having seen TK and Patti Soong, my grandparents. They exist only as ghosts, shapeless shadowy imprints on my consciousness. Sometimes I wonder if there is any chance that I might have liked them, loved them. Even ghosts and shadows are capable of being loved, after all. But always, the answer is ‘No’. I would not have loved them even if I had known them, because when the debits and the credits have been weighed, TK and Patti fall on the wrong side of the line between good and evil. It was their desire for Snow, my mother, to marry a rich man that pushed her into the arms of Johnny. Nothing can ever atone for that.

By the time Snow was of marriageable age, Johnny was already well known across the valley. He was the sole owner of the most profitable trading concern in the valley and was widely admired in all circles. As with all beautiful young women of a certain background, Snow had already had a good deal of experience of suitors and tentative matchmaking. All of these possibilities had been created and choreographed by her parents. They took her to Penang, KL and Singapore, where she was displayed like a diamond in a glass box. Yet it was closer to home, at the races in Ipoh, that they found the first serious contender. He was a beautiful-looking boy with a powder-pale complexion to match Snow’s. He had large, clear eyes and stood tall and erect with all the dignity you would expect from a son of the Chief Superintendent of Police. When he was introduced to Snow he kissed her hand – kissed it – a gesture he had learned during his days travelling in Europe. He complimented Patti on her sumptuous brocade dress and quietly whispered a tip for the next race in TK’s ear.

It wasn’t long before Snow and the Superintendent’s son were allowed to take tea together. They sat exchanging polite conversation. She talked about books – novels she had read – while he nodded in agreement. Although TK and Patti were pleased with his dignified manner and solid background, it was his family’s home which brought greater excitement to them, for the Superintendent had recently built a modern, Western-style house in which many of the rooms had wall-to-wall carpets. The main dining room had one wall of pure glass so that it served as an enormous window. Such daring was indicative of considerable wealth, an impression which was confirmed by the quality of the jade jewellery worn by the boy’s mother: dark in colour with a barely marbled texture. To top it all, Snow and the boy looked such a pretty pair and would surely attract all the right comments when the time came for them to venture into the public eye.

Thankfully, before such an understanding was reached between the parents, TK and Patti discovered that the boy’s parents were not quite as wealthy as they seemed. The Superintendent’s lavishness at the races had taken its toll on the family’s finances, and it was thought that much of his wife’s fabulous jewellery was borrowed from sympathetic relatives. It was clear that the dowry which TK and Patti expected in return for the hand of their daughter could never be fulfilled.

Scarred by this experience, TK and Patti became cautious and especially thorough in their appraisal of potential suitors. They asked many questions, they made enquiries. They did not want to make the same mistake twice. In letting the match with the Superintendent’s son progress to the extent it did, TK and Patti had been careless. One such mistake was forgivable; two mistakes would not be. Not only would it reflect badly on them, it would also diminish the value of Snow’s attractiveness. The size of the dowry would almost certainly be smaller. Yet their diligent investigations made the prospect of a match more and more remote. Every search turned up some unpleasant detail about the family in question, ranging from full-blown scandals to questionable associations: lunatic grandfathers, homosexual uncles, bastard children, gambling debts, hushed-up divorces.

The plain truth of it was that it was 1940, and there was little money in the valley, certainly nothing that could match the wealth of the Soong family. Snow was not yet twenty. There was still time, but a suitable match had to be made soon.

For all their meticulous planning, TK and Patti’s first proper meeting with Johnny was precipitated by events beyond their control. It so happened that a new man was appointed as head of the British mining concern in the valley, a fine young gentleman called Frederick Honey. He arrived with impeccable credentials, having gained a rugger Blue at Oxford and a keen grasp of tropical hygiene and colonial law from the School of Oriental Studies. His reign over the British tin-mining enterprise was, ultimately, short-lived, for he was lost to a boating accident in 1941, when he drowned in the waters off Pangkor island in a treacherous monsoon storm; his body was never found. It is clear, however, that during his short tenure in the valley, he was much admired. TK Soong was, as you can imagine, quick to see the value of having Mr Honey as an ally, and eager to make an impression on this formidable new tuan besar as soon as possible. It was decided in the Soong household that a gift should be sent to Mr Honey, something instantly suggestive of the Soongs’ status and influence in the valley; something unusual and beyond the reach of an Englishman newly arrived in the country. But what? A whole roast pig, perhaps? No – too ostentatious. A scroll of the finest Chinese calligraphic paintings? No – not grand enough.

‘How about some textiles,’ Patti said in desperation to her husband. ‘From that man, what’s his name – Johnny Lim?’

TK paused. He was inclined to dismiss the idea at once, but the paucity of previous suggestions persuaded him to consider for a moment. He paused for quite some time. ‘It’ll be fruitless,’ he said, but nonetheless decided to summon Johnny to the house.

Johnny had long since ceased to tour the countryside by bicycle, but the call of TK Soong was one he could not resist. He arrived at the house and found himself seated in the enormous room in which the Soongs received their visitors. Its vastness amazed him; his eyes could barely take in the details of its space: the rattan ceiling fans rotating slowly, arrogantly, barely stirring the air; the softness of the light through the louvred shutters; above all, the books, which lined an entire wall, row after perfect row.

‘We have heard many good things about you,’ TK said as Johnny began to unpack his bags on the table which had been specially set up for him. ‘Thank you,’ he said, still marvelling at the books.

Behind his back Patti tugged at TK’s sleeve. ‘How old is he?’ she whispered. She had heard that Johnny Lim was a young man, and in her mind’s eye had pictured a wild-haired, loud-mouthed tearaway with dirty fingernails. Yet before her stood someone neat and compact, who seemed almost middle-aged, whose movements were laborious and heavy with experience. A fleeting image tickled her imagination: Johnny and Snow seated on bridal thrones of the type that perished with the death of nineteenth-century China. ‘I must say, Mr Lim,’ she said as she fingered a piece of English chintz, ‘now that I see your wares, I can understand why people are so complimentary about you. About your shop, I mean.’

Johnny lowered his head and did not answer. He unfolded a length of songket, its gold threads shining and stiff and stitched into an intricate pattern.

‘This piece of cloth, for example,’ Patti continued, running her hand over a piece of brocade, ‘is very beautiful. Very fitting for a woman, wouldn’t you say?’

Johnny nodded.

‘Not for an old woman like me, of course, but for a younger woman. Do you agree, Mr Lim? It must be very popular with fashionable ladies.’

‘No, not really,’ he said truthfully. ‘It’s too expensive.’

‘Ohh, Mr Lim,’ Patti laughed. ‘Truthfully, do you think it would suit a young woman? No one very special or very beautiful, of course.’

Johnny half shrugged, half nodded.

‘Would you mind if I asked my daughter to see this? I’m sure you’re too busy to spend much time with her, but if you could spare a few moments –’

‘I would be pleased to meet your daughter,’ Johnny said. His pulse quickened. Even though he had heard about the Soongs’ famous daughter he had not for a second thought that he would be introduced to her.

‘I’m sure you’re just saying that to be polite, Mr Lim,’ Patti said with a laugh as she got up to leave the room. ‘After all, my daughter is hardly worth meeting. I’m sure you will be disappointed.’

‘I’m certain I will not.’

‘If you insist,’ Patti said, disappearing out of view.

A minute elapsed, and then another, before she reappeared. ‘My daughter, Snow,’ she said.

It took Johnny several moments to gather himself. She was a disappointment, a shock. He had expected a tiny, exquisite jewel, but instead he found himself looking up at a woman who seemed to tower endlessly above him. He breathed in, trying to swell his chest and lift his shoulders to make himself taller. When he looked at her face he found her staring intently into his eyes, and he quickly lowered his gaze. He felt embarrassed, cheated – though he did not know of what.

Poor Snow. She had grown used to being courted by lively, attentive men, but now she was confronted by a suitor who seemed more interested in his fingernails. At one stage she noticed he was gazing at a spot just above her collarbone, and for a brief moment she thought that he was staring at her neck. Then she realised he was looking at the books on the shelf behind her. She tried to engage him in conversation, but it was no use. This curious man sat like a deaf-dumb little orphan child before her. He was small and dark with an impenetrable moon-face. She searched for some clue as to what his character might be and concluded that there was none: no character whatsoever. She began to feel sorry for him. Later, her parents told her that he was a textile merchant, very rich and well known. Snow had not heard of him. As she watched him leave the house, she knew, from the glow of contentment on her parents’ face, that all parties had reached an understanding. The negotiations – the courtship – would soon begin, but the business had already been concluded. That afternoon, TK and Patti had bought from Johnny a few lengths of songket and some hand-blocked European cotton, which would in turn buy them favour with the British. And as for Johnny, he had gained himself entry into a world he had always dreamed of.

Johnny and Snow’s first organised meeting was, unusually, in public and unsupervised. TK and Patti felt that given Johnny’s impeccable and restrained manners, it would not be imprudent to allow the pair to meet in such a way. They were not afraid of the gossip which would inevitably follow. This was, after all, an alliance they wanted people to talk about. All their instincts told them that this was a match they should be proud of.

When Johnny and Snow appeared at the new picture house in Ipoh, a gentle commotion broke out in the crowd. Every head turned to see if the whispers were true. Was that really Johnny Lim – at the pictures? And was he here with TK Soong’s famous daughter? What did she look like? Where was she? For most people it was too much to bear, and throughout the film, a constant murmur of voices filled the auditorium. It was the first time many there had ever seen Snow. Men leaned forward in their seats, peering down the aisle just to catch a glimpse of the back of her head; women touched their own faces, noticing all of a sudden how plain they looked compared to her. And when the lights came up there was pandemonium. Johnny and Snow were nowhere to be seen.

Afterwards, the couple dined at the famous Hakka Inn. For Johnny, it was the realisation of many childhood fantasies. They were presented with roast suckling pig and jellyfish, black mushrooms and abalone, steamed grouper and a large dish of noodles. These were things he had never eaten before. He felt ill at ease going to smart restaurants. They were too bright for him, too full of movement and voices, and he always felt as if he was being watched as he ate. He had only ever been to restaurants to celebrate the conclusions of particularly large business transactions. This time, he tried to think of the experience as the biggest business venture of his life. Because to him, it was.

Once Johnny had overcome his initial awkwardness, however, he began to notice how rich and sweet the food tasted. He ate quickly, sinking deliciously into this new-found land of honeyed aromas and silken textures. He was like the rat in the childhood proverb, dropped on to a mountain of fragrant rice grain.

‘The food is good,’ he said. She did not know if it was a question or a statement, so she simply nodded, and he returned to his solitary feast.

Snow watched him feed. She wondered, as she always did when she was sent to meet a new suitor, whether she would be happy with the man before her. She always took it for granted that she would end up as the man’s wife. The choice was not hers, and accepting her fate early would make it less of a shock. So far she had not met anyone with whom she thought she could be happy. Even the Superintendent’s son, beautiful though he was, would have been unsuitable as a husband. He was far too inward-looking and concerned with the neatness of his clothes to notice her. Living with him would have been like gazing at the stars. A marriage could not be happy if the husband was prettier than the wife, that much she knew.

This new man did not bring her much hope either. As she saw it, the problem was not that she considered herself beyond his reach (beautiful wives and ugly husbands often made good matches), but that he did not seem to appreciate that she was at all attractive. For a while she entertained the idea that he had been tragically hurt by the death of a lover. He had a reason for being withdrawn, a sad and compelling story. She looked closely at his face for signs of a life or a love lost. She found him attempting to force an entire black mushroom into his mouth. This particular one was larger than the others, and he was having difficulties. He stretched his mouth sideways like a smiling fish in order to accomodate it; his lips quivered in an attempt to accept the sumptuous gift from the chopsticks. Eventually he succeeded, but then, after a few uncomfortable chews, was forced to spit the mushroom on to his plate. It landed softly on the gravy-soaked rice, and he repeated the whole exercise, this time succeeding easily. His chopsticks immediately reached for another mushroom, and he noticed Snow looking at him. His lips were thick and slicked with grease.

‘The food is good,’ he said, raising his eyebrows slightly.

She nodded, eyes fixed on his lips. No, she thought, there is no love story here. He was not capable of love. It was better that she prepared herself for this now.

He walked her to the bottom of the steps leading up to her house. All the lights were out, which usually meant that Patti was listening at the darkened window.

‘The evening was enjoyable,’ Johnny said. Again, Snow was not sure if this was a question, but all the same she could not bring herself to agree.

‘I am sure I will see you again,’ she said, and went into the house, walking swiftly to her bedroom to avoid her mother’s interrogation. Strangely, she did not hear Patti’s footsteps nor the opening or closing of doors. The house was full of a confident, approving silence.

Six months later they were married, after a courtship which, as TK would say, was ‘full of propriety and politeness’. Johnny moved into the Soongs’ house while he searched for a new home for himself and his wife. During this time he revelled in the Soongs’ hospitality, becoming so accustomed to it that he almost believed it was he who was being generous and welcoming: the lavish parties were thrown by him; the elaborate dinners were prepared by his cooks; the people who came to the house were his guests. To these guests, it seemed obvious that the sumptuous events were paid for by this rich new tycoon, and Johnny did nothing to dispel this presumption. Instead, he adopted a demeanour of excessive modesty to fuel the belief that he was indeed the magnanimous, yet somewhat reticent, host.

Guests: Thank you, Mr Lim, for such a splendid dinner.

Johnny (as self-effacingly as possible): Oh, please, no – thank Mr and Mrs Soong. This is, after all, their house. They have enjoyed having you here this evening, I know.

Guests (to themselves): What a noble, honourable man is Johnny Lim, too gracious even to accept thanks. How respectful to his elders, how civilised, etc., etc.

For the Autumn Festival in the year they were married, for example, the festivities at the Soong house were referred to as Johnny Lim’s Party, even though he had nothing to do with it. That he played no part in its organisation is clear from the extravagant yet tasteful nature of the evening’s revelry and the type of people who were in attendance. It was the first significant function at the Soong household since the marriage of Snow to Johnny, and it was an event that was talked about years afterwards. Many of the guests were English – and not just the District Education Officer either, but luminaries such as Frederick Honey and all the other tuan besar of the British trading companies. It is said that even Western musicians from Singapore were engaged to perform for the evening. A striking operatic troubadour, six and a half feet tall, sang whimsical songs in French and Italian. His face was daubed with theatrical paint which obscured his fine features, but even so, everyone present commented on the delicacy of his looks and the flamboyance of his costume – a flowing cape of Ottoman silk lined with iridescent scarlet. He sang so angelically and played the piano with such lightness of touch that no one could believe that he had not come directly from the great concert halls of Europe. ‘What is someone like him doing here in the FMS?’ people wondered aloud as he improvised familiar songs, teasing his audience. The noble Mr Honey sportingly lent himself to all the women as a dancing partner; he skipped to a traditional Celtic tune, linking arms with his companions as their feet clicked lightly on the teak floorboards. Johnny stood awkwardly in a corner, surveying the scene, trying his best to seem proprietorial and calm. He smiled and tried to tap his foot to the music, but couldn’t keep in time. A scuffle broke out among the servants in the yard outside, and it was up to the magisterial Mr Honey to restore peace. All night there was a constant stream of music to match the flow of alcohol. ‘It’s at times like these,’ the guests said, watching Mr Honey regaling a group of men with stories of adventure, ‘one almost feels glad to be in Malaya.’ At the end of the evening, when the air was cool and the tired guests began reluctantly to drift home, they realised that the music was no longer playing; the lid of the piano was firmly shut. As the guests departed from the darkening house rubbing their aching temples, they struggled to remember what had happened throughout the course of that evening: it had been too wonderful to be true. Had he really existed, that painted troubadour? He had simply vanished, phantom-like, into the tropical night. What a marvellous party Johnny Lim had given, they thought; what a marvellous man he was. They certainly made a lovely couple, Johnny and Snow.

Only one photograph survives of my mother. In it, she is wearing a light-coloured samfu decorated with butterflies. The dress clings delicately to her figure, slim and strong like the trunk of a frangipani tree. Her hair is adorned with tiny jewels too small for me to identify. When I hold a magnifying glass to the picture the poor quality of the old paper makes the image blurred and soupy. Her face is young and soft. Sometimes, I stick the photo into the frame of a mirror so that I can see my own face next to hers. My eyes are her eyes, I think. The photo is too old to give me any more clues. I found it when I was fifteen, in an old tin box in Father’s closet, together with the pictures of Tarzan. It was in a cracked leather frame far too big for it, and when I looked carefully I could see that it was because the photo had been carefully torn in half. Two, maybe three other people would have been in it, but only my mother and father remain, sitting close to each other but clearly not touching. They sit at a table at the end of a meal; before them the remains of their feast appear as dark patches on the white tablecloth. Behind them, merely trees. Beyond those, a part of a building – a ruin, perhaps, somewhere I do not recognise. I am certain it is not in the valley. Throughout the years I have looked at hundreds of books on ruins: houses, palaces, temples; in this country and abroad. Not one resembled the place in the photo. I do not know where it is. Perhaps it does not even exist.

On one side of this incomplete portrait, a hand rests on my mother’s shoulder. It is a man’s hand, of that I am certain. His skin is fair – that too is obvious. On his little finger he wears a ring, probably made of gold. It looks substantial, heavy. Time and time again I looked at the ring through my magnifying glass, but it gave me no clues. It was just a ring.

I took the picture and hid it in my bedroom. Father never mentioned it, and neither did I. I wanted to ask him whether there were any other photographs of my mother, but I never did, because then he would have known that I had stolen the picture. I never dared ask him about my mother; I never knew what questions to ask. Besides, I know he would not have told me about her even if I had. All I have to go on is that single photograph. Whenever I look at it I fold it in half so that Johnny is hidden and I can only see my mother.

A few years ago, I did something I thought I would never do. I succeeded in visiting the old Soong home, the house which my mother and father lived in. I had always known where it was, tucked away a mile or so off the old coast road, west of the River Perak, yet I had never seen it. Partly this is because it is difficult to get to. There are no bridges here, and to get across the river you have to drive a long way south and then double back, travelling slowly northwards along the narrow roads that wind their way through the marshy flatlands. During the latter half of the occupation, the house was used by the Japanese secret police as their local headquarters. They brought suspected communists and sympathisers there to be tortured in the same rooms where TK and Patti and Snow and Johnny once slept. The cries of those tortured souls cut deep into the walls of the house, and when I was a boy I knew – as all children did – that the place was haunted. In those days I did not know that the house had been Snow and Johnny’s. Back then it was merely one of those things which children feared in the same way they feared Kellie’s Castle or the Pontianak who fed on the blood and souls of lone travellers on the old coast road. We were taught to fear these things and so we did, never once questioning them. We believed in those things as we believed in life itself. When, several years ago, I finally learned of the significance of the house, I simply smiled, as if someone had played a joke on me.

How funny it is that the history of your life can for so long pass unnoticed under your nose.

When I say I ‘visited’ the Soongs’ old home, I am exaggerating slightly. My first attempt to visit the place was not entirely successful. I had planned everything meticulously, but in the end my efforts proved to be fruitless.

I decided to go as a Tupperware salesman. This was the first thought that came into my head and it seemed a sensible one, as Tupperware was all the rage in the valley at the time. I purchased a large selection of Tupperware in different colours and sizes and loaded it into my car. I stole a brochure from my dentist’s waiting room and bought a new briefcase into which I packed several ‘order forms’ which I had typed myself. I put on a tie, of course, and combed my hair differently. I had allowed my hair to grow longer than usual, as I thought this would help me to feel like a different person. I gave myself one last look in the rear-view mirror of my car before I set off, and I was pleased with what I saw. My own mother would not have recognised me.

The door was answered by a pubescent child – a girl, I think, though she was dressed as a boy. I searched her face for a resemblance to me but found none. She stared at me with fierce eyes.

‘What are you selling?’ she snapped. She sounded much older than she looked.

‘Tupperware,’ I said, suddenly feeling confident at the sound of the word. I stepped aside and pointed at my car. Large piles of Tupperware rose into view through the windows.

‘We don’t need …’

‘Tupp-er-ware,’ I said slowly. ‘Would you kindly ask your mother?’

‘She’s not here.’

‘Anyone else here?’

She closed the door and bolted it. ‘There’s a tall man selling things,’ I heard her call out to someone inside. When the door opened again a young woman stood at the entrance. She looked at me coldly but did not speak.

‘I’m selling Tupperware,’ I said. ‘It’s from America. It’s very useful.’

She remained silent. I felt my nerve begin to weaken. I had to make a final attempt. ‘May I come in and show you?’ I smiled.

She held my gaze for several seconds. I held my breath to hide my nervousness and tried not to blink.

‘OK,’ she said and let me in.

I stood in the middle of the large sitting room and looked around me. The room led out to a verandah which ran along the entire length of the back of the house. Through the half-open shutters I could see that the land fell away to the jungle, which appeared as a soft green carpet. The walls of the room were decorated with long scrolls bearing Chinese calligraphy. They were executed in a flowing and flamboyant hand, the characters swirling and greatly exaggerated. One scroll caught my eye. It was the famous Tang poem by Li Po:

Moonlight shines brightly before my bed,

like hoar frost on the floor.

I lift my head and gaze at the moon,

I drop my head and dream of home.

‘What are you looking at?’ the woman said. She had a slim face and clear skin. She too looked nothing like me.

‘I was just admiring your calligraphy,’ I said. ‘It’s very beautiful. Did you do it?’

‘No,’ she said, suppressing a smile. Her shoulders dropped and her voice became softer. ‘No, that was done by my great-uncle.’

‘Really?’ I said. ‘He must be a famous artist.’

She giggled. ‘No, he wasn’t. He’s dead now. He died during the war. My family saved all his paintings from the Japanese, and we put them back on the walls just like they were when Great-Uncle TK was alive.’

‘That’s interesting. He died during the occupation, did he? What was his name? Maybe I’ve heard of him.’

‘TK Soong,’ she said. ‘Say, you’re asking a lot of questions, aren’t you?’

‘Oh, I apologise. It’s not every day a poor salesman like me sees calligraphy of this standard, you see.’

She smiled again.

‘And like I said, I may have known him.’ I looked at the scrolls once more, keeping my back to her so she could not see my eyes. Though my head remained tilted upwards my gaze scanned the sideboards and cupboards for signs of photographs or mementoes – anything.

‘I don’t think you could have known him,’ she said. ‘How old are you, exactly?’

‘Look who’s asking questions now,’ I laughed. ‘How old do you think?’

‘Let me see …’ she said. I turned round and presented my face to her, smiling. ‘I’m usually good at guessing people’s ages, but you’re difficult.’

Behind her I caught sight of myself in an old mirror. The glass was scratched and blurred and dusty, silver strips peeling away behind it.

‘Why are you touching your cheek?’ she said. ‘Are you all right?’

‘Yes,’ I smiled. ‘So how old am I?’

‘I’d say in your forties. Late forties maybe.’

I opened my eyes in mock horror. ‘Not too far wrong.’

‘Then you definitely wouldn’t have known Great-Uncle TK. Or if you did you must have been a tiny baby. He died in 1943.’

‘How did he die?’

‘Well …’ she said, looking at her fingers, ‘you know …’

‘I’m sorry I asked. I’m just a stranger after all.’

‘It’s OK, really. I’ll tell you – the Japanese. That’s what everyone says. I don’t know the details.’

‘Did he have any children?’

‘Just one. My mother’s cousin. No, second cousin – I’m not sure.’

‘Did she live here too? Your great-uncle’s daughter, I mean.’

‘Of course. Don’t all children live with their parents? In fact, she lived here even after she was married.’

‘That’s nice.’

‘She was married to Johnny Lim, you know – the notorious Johnny Lim.’

‘Oh yes, I think I’ve heard of him – I’m not from around here, you see.’

‘Oh. Where are you from, then, Mr Tall Man?’

‘KL.’

‘Wow, long drive.’

‘It’s not bad. I stay in Ipoh for a week at a time.’

‘Sounds like you miss home.’

‘Not really. So, your mother’s cousin who was married to Johnny …’

‘Lim.’

‘Johnny Lim, yes. I guess that must have been her room,’ I said, pointing to a door which seemed to open into a larger room.

‘No, that was my great-uncle and great-aunt’s room. That one was Johnny and Snow’s,’ she said, pointing to a closed door. She paused and looked me in the eye, as if remembering something. ‘Hey,’ she said, taking a step towards me, ‘how did you know my great-uncle’s child was a girl? I didn’t tell you it was a girl.’

‘Supernatural powers.’ I tried to laugh but my face suddenly felt hot.

Just then an old man’s voice called out from behind the closed door. ‘Who is it, Yun?’

‘No one, Grandfather. Go back to your nap.’

The door opened and a bald, bent-over man emerged. He had sparkling clear eyes which widened when they saw me.

‘Good afternoon,’ I said, trying to sound cheery. ‘I’m selling Tupperware.’ It sounded like a lie.

I did not recognise him. I was certain I had never seen him before, and what’s more, I was sure that he had never seen me. And yet the way he looked at me made me nervous.

‘I know you,’ he said.

‘Oh really?’ the young women giggled. ‘You know this guy, Grandpa?’

‘Your face,’ he said. ‘I know your face.’

‘Who is he, Grandpa? Tell me,’ the young woman said. ‘I’m dying to know.’

‘Excuse me,’ I said suddenly, ‘excuse me for interrupting your afternoon.’ I walked towards the door, opening it in one swift motion, and when I reached the top of the stairs I began to run, leaping three steps at a time.

‘Hey, Mr Tall Man, what about the Tupperware?’ the woman shouted as she came after me.

I didn’t look back as I drove away on the dry, dusty road that wound its way through the plantation. The car jolted over rocks and potholes but I didn’t ease off until I reached the main road. My face was hot with embarrassment and anger. I had still not seen the room my mother had slept in.

By the time I reached home I had resolved to go back to the Soong house as soon as I could.

And so a few months ago I went there again. I had left a gap of about six months – plenty of time for me to regain my composure and for the people at the house to forget the strange travelling salesman who had fled before selling anything. I drove through the swampland with the sea-salty air swirling through the open windows. I left the car and walked the final mile to the plantation, my stride measured and calm. It was a night of perfect clarity, you must believe me. The moon was bulbous in a velvet sky and made my clothes shine. I stopped and looked at my hands and saw that my skin, too, had become pale and phosphorescent.

The house was dark. It looked exactly like the house from my childhood nightmares. It was waiting, ready to take me. I walked up the steps and tried the front door. I put my ear to it and listened for movement. Nothing. I walked along the verandah to the shuttered teak doors and put my hand on the rain-washed panels, pushing gently. They fell open at once, making no noise. The room burned with moonlight; where it fell on the floor the boards turned a startling white before me. I saw my reflection in the mirror. When I reached out to touch it, it shattered into a thousand pieces. In the broken pieces I could see parts of my face and they were hot to the touch. I stepped over the shards of glass and walked towards Snow’s room and stopped at the threshold before entering. I came into a small windowless anteroom. I could make out two chairs and a coffee table. At the far end of the room I noticed another door and made my way towards it. I know this door, I thought, I know this place. I have been here a thousand times before. I have carried it inside me since I was born and I know all that it held within it. A bed. An old man asleep on it. Next to him, a beautiful woman: Snow. The walls are hung with waterfalls of hot red silks. Snow opens her eyes and rises to sit up. Her hair is sleep-tangled but I can see her eyes have not shut. They have not rested for many years now. She turns to me and smiles. Come, she says and I walk slowly to her. She holds her arms wide open and I kneel before her slowly slowly lowering my head into her breast. Her arms close around me, her hands stroke my hair. Don’t cry she says don’t cry my child my son. Her fingers smooth my face my cheek my brow my dry cracked lips. With her long white fingers she pulls her white blouse aside and gives her white breast to my mouth. Drink my child my son she says and I drink. When I finish I can smell my breath and it is sweet and soft. Are you happy my son she says and I nod. I feel something cold and hard on my cheek and when I turn my face I see it is a pistol, Johnny’s pistol. She turns her body and lets me see the old man on the bed. I do not see his face but I know it is Johnny, I know it is. She puts the pistol in my hand and her lips to my ear. Her breath is cool and powdery and flutters like a moth. Shoot him she says shoot him for all the things he has done. Once more I bury my face in her breast but she is laughing pushing the pistol into my hand. Shoot him. Her skin is wet with my tears. Mother I say. The gun is cold and hard, her skin is soft and wet. Don’t cry my son she says don’t cry. I cling to her with all my life and she kisses me on my forehead.