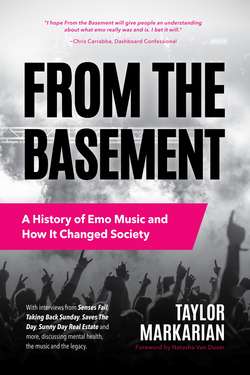

Читать книгу From the Basement - Taylor Markarian - Страница 16

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеThe word “emo” has quite nearly overshadowed the music it attempts to describe. Actually, many people would claim that it has. Depending on who you ask, the word “emo” is either an unwanted shackle or a suitable shoe. Half of the people who grew up playing in bands that generally fall under this category hate the word because it was something somebody outside of the scene came up with. For my part, when I was in middle school and high school, “emo” was definitely thrown around as more of an insult than the name of a genre. To be labeled “emo” was to be cast as an outsider. If you were dubbed emo, something was wrong with you. But at the same time, I liked the fact that I was emo. I thought the bands that I listened to, like Taking Back Sunday and The Used, were emo, and I loved them for that because they were painfully honest about pain. Babs Szabo, one of the cofounders of the now extremely popular club event Emo Nite, happens to feel similarly:

“I think even at the time when the term ‘emo’ was viewed somewhat negatively,” she says, “it still didn’t impact people wanting to be a part of the culture. When I was in high school, it definitely was not cool to be emo in school. But outside of it, when you went to see shows, that’s when you were part of a community. That was the only time I felt like I was a part of something and not an outsider.”

Ethan Fixell (Kerrang!): “There’s nothing about true, legitimate emo that’s worth making fun of. Some would argue that we have Jimmy Eat World to blame, as the success of their single ‘The Middle’ opened a path to mainstream success for pop punk bands, and the lines between genres became so blurred that emo became a catch-all term for pop punk with whiny vocals and sensitive lyrics—music that’s easy to ridicule as saccharine or cheesy. By 2004/2005, the term ‘emo’ would become a punchline. (For the record, the term seems to be gaining dignity over time, especially with the fourth wave of emo bands that now pay homage to first and second wave acts.)”

William Goldsmith (Sunny Day Real Estate): “The whole emo thing…so this is not meant to be in anyway insulting to anybody that is into that label, but in the punk rock scene, the first time I ever heard anybody use that word, it was a way of insulting someone. I had never heard that before, but it was very obvious it was an insult. I don’t really know what happened, but I guess somebody in the industry had to come up with a way to sort of market it or put a label on it. At that time, there was grunge. Now here was this other thing, and they were like, ‘Shit, what are we gonna call this?’ When I found out that there was a new genre of music called emo and that we were one of the pioneers of it, I was like, ‘WHAT?! Wait! That was the insult! It’s not a genre of music!’ So that was kind of hard to deal with.”

Matt Pryor: “The term ‘punk’ was derogatory initially, too. It’s an evolution of language, but it is very much a case of outsiders.”

Shane Told (Silverstein): “The main [movement] I’d say I would compare [emo] to is the goth movement. Really, the emo thing was an extension of that, repackaged and repurposed. Now, ‘goth’ made sense because ‘goth’ stood for ‘gothic,’ which everyone thinks of as dark and black. But ‘emo’ is such an easy-to-make-fun-of word. ‘Oh, you’re emo.’ So I think it was really easy for somebody who had no association with it […] to poke fun at it. You could poke fun at it based on a guy like me, up there borderline crying on stage. Or, you could poke fun at some girl who has her hair fourteen different colors and piercings in her face.”

Tom Mullen (Washed Up Emo): “After 150 plus interviews for my podcast, the tag ‘emo’ still has weight to this day and has survived while being the most hated word to describe a genre. [It] is pretty remarkable.”

Chris Simpson (Mineral): “I don’t love it, as terms go. To me, it doesn’t feel useful in the sense that such a large amount of things have that term slapped on it; a lot of different sounding bands, to my ears. It seems to be more of an aesthetic than a sound. I don’t know what it means, really.”

Steve Lamos (American Football): “I don’t know why people associate us with [emo]. I guess ‘cause of Mike [Kinsella]. Nobody really cared about American Football when we existed the first time. I think there’s been some interesting revision of history as people have picked up on that first record, and now they associate us with that music in a way that I certainly don’t think they did at the time. I thought of The Promise Ring or Grade or Cap’n Jazz as that genre. But I have no idea why American Football is necessarily included in that, other than the Mike connection. But if that’s the kind of music that attracts the weirdos and the people who feel like a square peg in a round hole, then I’m fine with it. Nobody really seems to want to claim this title for themselves, but maybe that’s what emo means.”

Ian MacKaye: “Thursday…are they an emo band? The Promise Ring? Jets to Brazil? So, anything that Blake [Schwarzenbach] was in…Huh. I don’t want to dismiss emo. It’s such an obscure form and so hard to define. I don’t know what the criteria is to be emo.”

Kenny Vasoli (The Starting Line): “If you sing about relationships and you have kind of a high voice, you might be in an emo band.”

Eddie Reyes (Taking Back Sunday): “People always said that we were emo, and we never ever thought we were. To us, the real emo bands died out in the late ‘90s. For some strange reason, someone in some big magazine decided to attach that name to the music that came out of the punk rock scene. It was just instant—everyone’s emo. My Chem never thought they were emo; they thought they were punk rock kids from Jersey. It’s kind of like when you watch Dave Grohl talk about the Seattle punk scene and all of a sudden they were grunge, and they were like, ‘What the fuck is grunge?’ ”

Chris Conley (Saves The Day): “It kind of depends on who you’re asking. I think it’s amazing, because I first heard the word ‘emo’ when it was about Sunny Day Real Estate and Embrace.”

Ethan Fixell: “The first time I ever heard the word ‘emo’ was while recording an EP with my high school band at Mike Watts’s Vu Du Studios in Long Island, New York. An engineer named Sean Hanney told me that our music shared a lot of similarities with a movement that was happening at the time: this ‘emo’ thing. He played me Saves The Day’s Through Being Cool, and I was totally into it. Shortly after, I read a piece in a 1999 issue of Guitar World by Jim DeRogatis that was titled, ‘Emo (The Genre That Dare Not Speak Its Name).’ ”

“Emo (The Genre That Dare Not Speak Its Name)”

by Jim DeRogatis (Guitar World, 1999)

Once again there’s a hard-rocking sound galvanizing the underground. You can call it post-hardcore. You can call it post-punk. You can take a step back and just call it indie-rock. Any name you choose is bound to prompt an argument with somebody, so you might as well bite the bullet and call it the name that nobody likes: Emo.

Tom Mullen: “The words ‘emo’ and ‘emotion’ are things I would see at early shows when screamo bands would pour out everything they had on the stage, and by the end they’d all be so tired and exhausted from the set. The entire time watching it would be this feeling of the show being on the brink of breaking, but it never does. That tension, that moment of feeling like the music can go anywhere […] is what emotional means to me and what emo has always meant to me.”

Chris Conley: “Anybody [who] says they don’t like emo that was part of emo is just fronting. It’s lame.”

Eddie Reyes: “I feel like the people that hate it don’t really hate it. I think that they are truly emo kids deep down inside that just think it’s cool to hate it. I’m a fuckin’ emo kid.”

It would seem that the jury is out on whether “emo” is a good thing or a bad thing. An entire linguistics class could be dedicated to this subject for how much trouble this little three-letter word has been causing. But, if you think about it, is it really that much of a surprise? Humans have maintained pretty poor relationships with their emotions for as long as they’ve had them. Every day we are puzzled, even baffled, by them. It’s hard for many people to look their emotions square in the eyes. Many flat out ignore their emotions, even though what makes us human is our capacity to think and, most importantly, to feel. So the word “emo” is intrinsically problematic because emotions themselves are intrinsically problematic. Calling someone or something “emo” is to blatantly and singularly identify them or it as not just having emotion, but having a more emphasized relationship with emotion to the point where it needs to be commented on.

Nobody ever self-described as emo to begin with because the people who were making the music already knew they were doing it with extreme emotion—that was the point. But people who weren’t making this music and people who weren’t feeling the types of emotions that these bands were articulating were at odds with it. That’s because it’s difficult for people who haven’t suffered to understand suffering, and suffering is a large part of what these songs and records were confronting. And what generally happens when people are confronted with something outside their comfort zone? There is resistance. There is degradation. There is othering. And that’s all because, initially, there is fear.

To control that fear, people gave it a name: Emo. Once something has a name, it can be easily packaged into a neat little box and contained. But if there is one thing that none of these bands wanted to be, it was contained.

“This is not pretty,” remarks Shane Told, vocalist of Silverstein. “[It’s] in your face. I think that and the screaming that was coming into the music, too…this was not background music. This is intense music and if you’re a fan of this, then you care about this and then it was like, are you all in or not? If I’m listening to this music, then I am listening to this music. That was when it became such a thing, when people’s lives started revolving around these bands.”

Jacob Marshall, the drummer of MAE surmises, “It wasn’t trying to brag about your conquests or achieving a certain lifestyle status. It wasn’t mindless, it was mindful. It was actually reflecting deeply on the things that hurt us or healed us.”

Reflecting deeply (and out loud) about emotions like pain and love is not traditionally culturally acceptable for a male, and the bands in the emo and screamo music scenes were mostly comprised of young men. Sure, it was okay for the likes of William Shakespeare and Edgar Allan Poe to do, but in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, the average man was not setting out to write a great sonnet. The prevailing mentality was that emotions were things that belonged to women.

Jacob Marshall: “In culture in general, there is a certain expectation of what masculine energy is supposed to be. When something shows vulnerability or invites the more reflective aspects of our nature and puts that front and center, that makes people who are, in a sense, trained to hide their emotions very uncomfortable. So it’s easy to make [emo] a derogatory thing. I’ve never thought of it as a limitation.”

Ryan Phillips (Story Of The Year): “Not to be derogatory, but it’s not hard to imagine a super jock guy to be like, ‘Man, this guy sounds like a pussy.’ But then you’ve got another guy or girl that’s more sensitive that’s like, ‘I’ve had my heart broken, and I feel like screaming to the world,’ or, ‘If my girlfriend cheated on me or broke my heart, I wish I could scream this right to her face.’ And to some people that really struck a chord. It’s okay to wear your heart on your sleeve. It’s okay to be emotional. That doesn’t make you weak. It doesn’t make you less than.”

Chris Simpson: “It didn’t feel like weakness to us—it felt like our strength. Across the board in punk rock and indie music at the time, there was probably some feeling that that was kind of a weak thing to do. I think that’s maybe why emo got such an easy and immediate backlash. But a lot of that had to do, I think, with the term. Critics and people on the outside put this little cutesy term on it that, to me, felt belittling to the content and the music. I listen to the power of some of the music, and there’s something very masculine about the music but also something very soft and feminine. It can kind of hold both of those things. You could write about anything. I think that should always be the case with any sort of art or expression. I think there are times throughout history where it kind of becomes something that you don’t do, that isn’t done.”

David McLaughlin (Associate Editor, Kerrang! UK): “It’s become a lot more commonplace to do so in recent times, but when I first got into emo, there weren’t a lot of artists around who articulated their personal pain and embraced their own faults and failings like this genre seemed to. So I think starting that conversation in the alternative music sphere was emo’s key purpose. You hear it said a lot now that ‘it’s okay to not be okay,’ but the first time I felt like that was true was through emo bands. When you consider how much more open the world is [now] about its issues with toxic masculinity, there’s an amazing trickle-down effect from artists who dared to be emotionally vulnerable back then. Especially when compared to the braindead, Neanderthal attitudes celebrated across the mainstream metal world (which was then equally dominant in the pop charts).”

Plenty of men and young boys who didn’t feel it was possible to talk about their feelings never got the help they needed because of such toxic masculinity. There was (and still is, albeit less so) a sweeping sense of shame and guilt to admitting to emotional suffering.

Jamie Tworkowski (To Write Love On Her Arms): “For us as a [mental health] organization thirteen years in, I know it’s true that we hear from more females than males. When I show up to speak at a college, there’s always more young women in the room than guys. I think what we see, and it’s sort of stating the obvious, but it’s sort of easier for women to talk about their feelings and to talk about their struggles. We get excited, and it’s always felt important to make it known that the work we do is intended to be inclusive. The work we do is for men and women.”

What emo music did that mainstream thought didn’t approve of was throw traditional macho behavior out the window. The bands who started to develop this sound and this scene were tired of the straightforward aggression and masculine posturing of other rock, metal, and punk genres. Emo and screamo bands didn’t want to fake a socially contrived sense of masculinity; they wanted to convey true emotions exactly as they were. At first, creating an inclusive community with their music was mostly just a byproduct of their creativity, but as the scene gained a greater following, there developed a distinct intent to preach inclusivity.

Ethan Fixell: “As much as we all love Black Flag or Bad Brains, I think hardcore punk fans were desperately yearning for music that was less politically charged and generally raucous, and more personal, reflective, and viscerally painful.”

Shane Told: “Punk music from before was like, ‘Yeah well, you don’t like me? Then fuck you.’ Emo was like, ‘You don’t like me and I’m really sad about it and I’m just gonna listen to The Cure and think about this and what’s gonna happen the next time I see you and how I’m gonna feel.’ That’s real. That’s different.”

Ryan Phillips: “The lyrics were a lot more vulnerable and a lot more sensitive and, I think, in the zeitgeist, it kind of caught on because people were craving that after listening to Limp Bizkit and Korn. Maybe I’m wrong on that, but that’s how I felt. I was so into the nü metal stuff, but then [I heard] Jimmy Eat World and Finch and Glassjaw. I remember the first time I heard Glassjaw, and that was like the death of nü metal for me. It was a relief from the macho-ness.”

Chris Conley: “After punk and grunge, everyone was still aggravated and alienated. Thank god emo came around because all of a sudden you were allowed to have your feelings. You were allowed to be who you are.”

Aaron Gillespie (Underoath): “We wanted to feel angst like punk rock did but inject a little melody into it… We all went to the garage and were angry or hurt or happy or sad and we made these songs and people resonated with them. Our influences were Glassjaw and Thursday and bands that were doing something really, really vital and really fresh.”

Emo music culture was brave enough to challenge the established idea of what it meant to be a man. It was brave enough and daring enough to admit that life wasn’t all nice and peachy and to convey what that frustration, sadness, or insecurity felt like without pulling any punches. In Everybody Hurts: An Essential Guide To Emo Culture, Leslie Simon and Trevor Kelley write, “In the end, being emo is all about having the kind of unwavering conviction that allows one to face the challenges of a new day.”

As time passes, far more people embrace the term “emo” and adopt it as their own, wearing their black eye like a badge of honor. (Ten points to you if you got the “There’s No ‘I’ In Team” reference.) As we grow more distant in time from its inception, “emo” increasingly becomes a legitimate descriptor for a crucial moment in rock history, rather than a slight to those who dare to interact with their feelings.

“I think one thing that’s been really true for our scene several times over,” says Chris Carrabba of Dashboard Confessional, “was that there was a lot of overlapping of different genres that were unified by the nakedness of the emotionality that the singer was willing to display. I listened to this music because it was so emotional. They’re singing songs about what it is to feel. It’s not love songs. It’s not heartbreak songs. It’s just about what it is to feel.”

To me, that’s what it means to be emo: being willing to feel the painful emotions as profoundly as the pleasant ones. It makes me proud to be emo, because, to me, the word symbolizes emotional strength. But, in the end, I really don’t get as hung up on the word as many of the bands that are described that way seem to. People could have used it as an insult, and they did, but those people’s definition of emo wasn’t the right one. To me, “emo” was the name that was used to describe the bands and the music I loved: the songs that saved my life. And that’s all it is—a name. I don’t care what it’s called. It could be any name in the world, and I would still look at it the same way. (And if I recall correctly, Shakespeare said something similar in a little play you may have heard of, Romeo & Juliet.) So enough of mincing words. Let’s talk about the goddamn music.