Читать книгу From the Basement - Taylor Markarian - Страница 19

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеOne of the most significant events in all of human history took place in 1991 when the World Wide Web became public. In 1992, the LA riots tore the California city apart. “The Macarena” craze sparked in 1993, Kurt Cobain committed suicide in 1994 (whether it was because of “The Macarena” remains to be seen), O.J. Simpson beat his murder charges in 1995, and Coolio released “Gangsta’s Paradise” that same year. The Spice Girls changed the world seemingly overnight with their hit song “Wannabe” in 1996. NASA’s Mars Pathfinder successfully landed on the red planet in 1997. In 1998, Monica Lewinsky and President Bill Clinton had an affair that would end up becoming the punchline of roughly 50 percent of all Eminem lyrics. And finally, in 1999, while the world was plunging into Y2K madness, virtually every notable boy band or female pop star came out with their biggest releases, from The Backstreet Boys’s “I Want It That Way” to Christina Aguilera’s “Genie in a Bottle” to TLC’s timeless “No Scrubs.” This was the historical background from which emo emerged: a pop culture explosion.

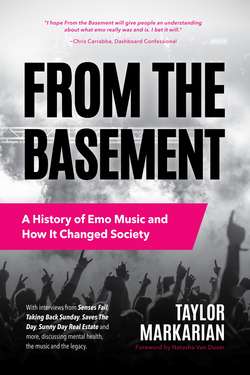

In the era of what most people claim to be the best of hip-hop and bubblegum pop, punk dove deep underground. It wasn’t front and center like it was in the 1970s. It wasn’t on the streets like hardcore was in the 1980s. Now, punk was in the basement, and that’s where it would begin to morph into something new. With the passing of Kurt Cobain came the end of grunge and the beginning of what would become known as emo—not that anyone knew it at the time. Sunny Day Real Estate, who also happened to be based in Nirvana’s home city of Seattle, were about to come on to the scene and change everything.

Ethan Fixell: “Some would argue Sunny Day were more alt-rock than emo, but they directly influenced more emo-related bands than any other artist on this list. While Mineral played it sad, and The Get Up Kids played it fast and snotty, Sunny Day were brooding and detached.”

Chris Simpson: “I think Sunny Day Real Estate and their first record, Diary, was the first kind of catalyst. Everyone knew Sunny Day Real Estate. There was a depth to them that I feel like a lot of punk rock that I had heard didn’t have.”

William Goldsmith: “All ages shows were illegal here in Seattle. It was tricky because Jeremy was eighteen, and I was just about to turn twenty-one. So we weren’t even old enough to play in bars yet. We were creating music that was specifically for us—it wasn’t for anyone else to hear. We didn’t think anyone was gonna be able to hear it, so we were making music for the sake of making music—because we wanted to. We didn’t expect to get out of the basement. There were no plans to play any shows. So it was deeply personal. When we started playing shows, it felt strange. It felt like somebody watching you go to the bathroom or something. Something that’s normally a very private thing. So that was kind of odd.”

The quality of the music they were making was higher than what one would usually find in a bathroom, however—much higher. With a touch of luck, their basement would soon turn itself inside out and put Sunny Day Real Estate in the spotlight.

William Goldsmith: “Somehow Kurtis Pitz was able to put on an all-ages show. Then there was this other band, Engine Kid, that was supposed to play with this band called Skirt at The Crocodile Cafe in Seattle. Engine Kid actually ended up not being able to play the show, so they told the booking agent they recommended they put us on the bill in place of them. So the booking agent put us on the show and we played and then he said, ‘Hey guys, I’m gonna put you as the very first band at the Sub Pop anniversary party show here at The Crocodile. I just wanna see what happens.’ We were like, ‘OK, whatever.’ So we played the show, and there was only one person in the room that was watching us play. I think it’s probably because Eric Soderstrom, the booking agent, went up to Jonathan [Poneman] and [told him] to watch this first band. We got done playing, and he just walked up to the stage—it was literally an empty room—and he said, ‘Hey, do you guys wanna make a record?’ We started laughing. We were like, ‘Yeah, right. What are you joking?’ And he was like, ‘No, because I’m Jonathan. I’m president of Sub Pop Records.’ Sunny Day Real Estate was able to make a record literally by accident. Ultimately, it was a total fluke.”

That “total fluke” would end up making some serious waves in rock history. When Sunny Day came out with Diary, it brought countless other bands out of their basements and into…well, other people’s basements (at first, at least).

Dan Marsala: “Sunny Day Real Estate and The Promise Ring, that was emo to us.”

David McLaughlin: “Everyone screams and shouts about how great Diary was (and it is), but [How It Feels to Be Something On] is so connected to my first serious relationship, the inevitable breakup, and how it helped me pick up the pieces again. A girl broke my heart, and this record helped me heal it—what an emo cliché!”

Chris Carrabba: “Sunny Day Real Estate had come before me. In zines and stuff, they had been called emo, so that’s what we thought they were. I was like, you know, obviously I’m not like Sunny Day Real Estate. Nobody’s that good.”

William Goldsmith: “You could say that to me, but it’s hard for me to wrap my head around. It’s really cool to have inspired anybody at all. We wouldn’t have existed without the same thing. We can point back to Fugazi. We can point back to Rites of Spring. All these different bands, they’re the reason our band existed. Our band was essentially an experiment. People had been playing hardcore for quite a few years. We come from music that isn’t good, but wasn’t necessarily meant to be good. It was a statement: a place to start. It was an experiment with guys who had been playing hardcore, trying to write songs and learn how to use music as a form of more sophisticated storytelling. This took me years and years to try to get a handle on and actually learn how to leave space for melodies. When Jeremy joined the band, that really enhanced that experiment. We had to focus even more because we finally had someone who could sing. Jeremy had also been playing hardcore, but […] he started when he was a little kid and sat in his room with a four-track and wrote songs like ‘In Circles.’ That was natural for him.”